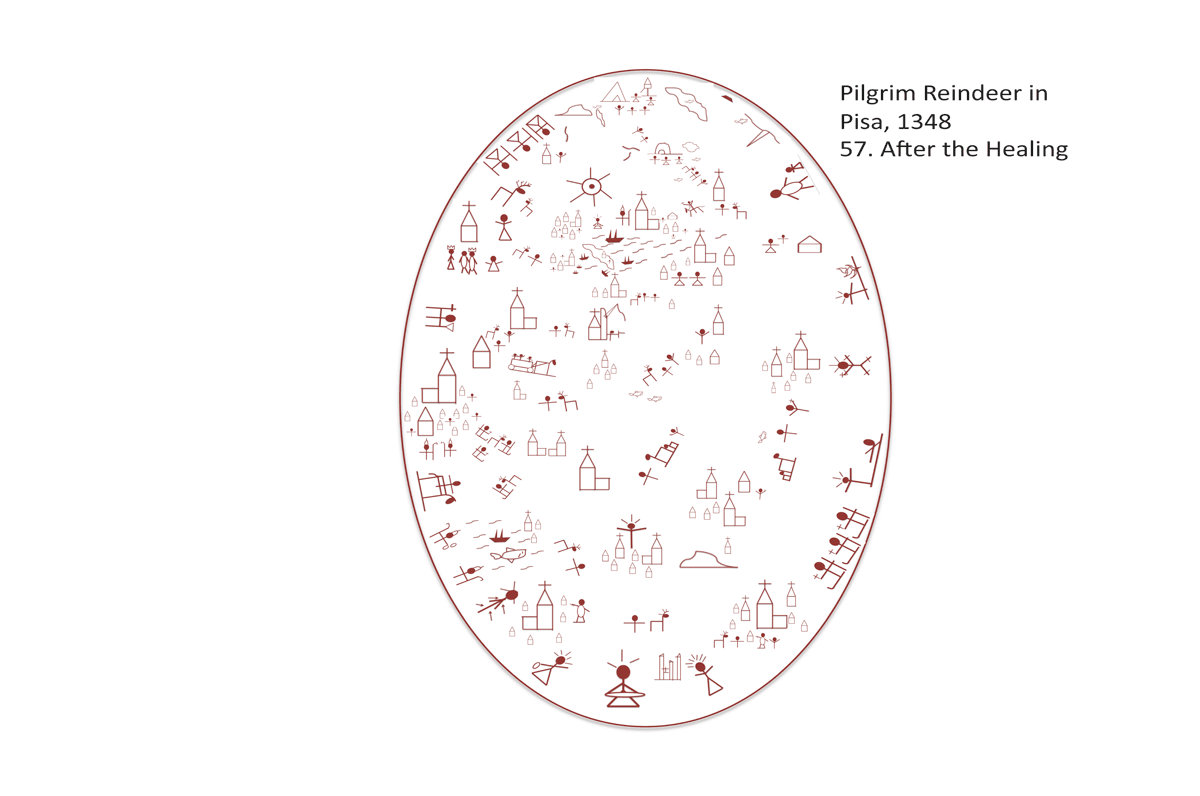

Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348

a free multimedia novel by

Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison

|

Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348 a free multimedia novel by Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison |

|

|

|

|

|

60. Epilogue

You have searched me, and you know me, Lord.

Much time has passed since Catharina Ulf’s Daughter said goodbye to Bávlos, grandson of Sálle in the forest outside of Pisa. Catharina, whom you first met in Chapter 14 along with her mother Birgitta, did not go home to Sweden as she had thought she would when she set Bávlos free. A vision from Christ informed her mother Birgitta that both women were to stay in Italy and there they dutifully remained for the next quarter century, until Birgitta’s death in 1373. Only then, with Birgitta’s sainted body in tow, did Catharina return to the land of her birth, where she started an order of nuns and priests who lived by a rule dictated by Christ to Birgitta at the renovated estate in Vadstena.

Throughout those Italian years, Birgitta continued to speak out about her visions, chastising clergy and royalty alike for their failings and conversing daily with Christ and his Mother. She worked hard to convince the several popes of her latter days to return to Rome from Avignon. She visited the Holy Land and was eventually canonized a saint.

Catharina, too, was celebrated as a saint, working miracles after her death and attracting much veneration throughout the northern lands. In churches in Sweden you can still find her portrait, often depicted with the “ wild deer” she saved from her husband’s hunt, her earliest attested miracle. It was said that the deer recognized in her a natural protector and rushed to hide itself behind her skirts. Of course, we know that Nieiddash was hardly a “wild” deer, although she had been more unruly than usual during the time of the rut. In any case, it is clear that she recognized the tender and loving nature of Catharina, something that Bávlos also noted from the start. Catharina was also said to have a strange ability to understand foreign languages, even the languages of Finns, and perhaps also Sámi.

Another famous Catharina, the little baby Catharina of Siena (1347-80), daughter of the cloth merchant Giacomo di Benincasa and his wife Lapa, went on to live a famous life as well. Bávlos met her as an infant in Chapter 53. Catharina grew into a powerful visionary, chiding the sinful for their misdeeds and urging the pope to return to Rome. In 1377 the pope complied: Gregory XI returned to Italy in response to her entreaties. It is not clear whether Gregory (see below) and Catharina ever knew of their mutual connection to Bávlos the Sámi pilgrim. Catharina, like Bávlos, was credited with stigmata, although hers remained invisible to the eyes of others. She was a woman who enjoyed going without food, subsisting for long periods on the Eucharist alone; like Bávlos, she often felt that she was sharper when engaged in fasting.

A stranger to all fasting, Buonamico Buffalmacco gained in girth, fame and fortune in the aftermath of the Plague Year. His sense of humor and style attracted the attention of his Florentine neighbor Giovanni Boccaccio (1313-75), who included stories of his exploits in his Decameron, a collection of tales set in the year of the Plague. Bávlos spent an evening having dinner with the famous poet in Chapters 44 and 45. In Boccaccio’s tale, a group of friends decide to flee the city of Florence to escape the Plague, and spend their days engaged in humorous storytelling at an estate near Mount Morello. Among the tales Boccaccio’s characters tell, you can read of Buonamico and his friend Calandrino as well as the medicus Master Simone. Calandrino’s estate near Mount Morello, for instance, is mentioned in the sixth story of the Decameron’s eighth day, where Buonamico conspires with another friend—an assistant named Bruno—to steal a pig from Calandrino. Buonamico had a weakness for pork. Master Simone is mentioned in the ninth story of the eighth day, in which Buonamico subjects him to a cruel practical joke that ends with the medicus being dumped into the fetid dung trench near Santa Maria della Scala, a latrine now, thankfully, long gone. Later on, in the third story of the ninth day, Master Simone helps Buonamico with another practical joke, convincing Calandrino that he is pregnant. It is unclear whether the Bruno of the Decameron, a character about which Boccaccio supplies few details, is actually our friend Bávlos, though the likelihood is great. You will find no explicit mention of Bávlos by name, however: it may be that the stigma attached to Bávlos as a suspected cause of the Plague, as well as his stigmata, rendered it impossible for Boccaccio to discuss him in detail in a work meant to entertain refined gentlefolk.

Buonamico’s paintings also prospered: the painter and historian Georgio Vasari (1511-74) praised Buonamico’s frescoes as great masterpieces. Later eyes disagreed, however, and many of his paintings were eventually painted over and destroyed. Vasari also knew about Buonamico’s run-in with the bishop’s pet monkey and many humorous stories of the painter’s apprenticeship, tales that indicate that Buonamico fully deserved the crafty Angelo as his assistant.

Buonamico’s Triumph of Death is today one of the painter’s only surviving works, and it survived only by a miracle. On July 27, 1944, exactly 595 years after Bávlos and Catharina said their farewells, a bomb from an American warplane landed by chance on the rooftop of the Camposanto, nearly destroying the site forever. The bomb’s explosion reduced whole walls to rubble, and lead from the building’s roof, melted by the ensuing fire’s intense heat, dripped onto Buonamico’s frescoes and marred them nearly irreparably. It took half a century to restore the damage that a single bombing created. Through it all, however, Buonamico’s painting of the monk and the reindeer survived, a testimony to a friendship and a cultural encounter that defied all probability.

The descendents of another local Florentine, Averardo de’ Medici, eventually transformed both the city of Florence and its society in ways that Buonamico could never have imagined. Buonamico had little to say of Averardo or his sons in Chapter 50. In the centuries following the Plague, Florence became the most powerful city in all of Tuscany, ruled by the Medici family that enjoyed a special status as bankers to the pope. Indeed, three of the Medici even became popes themselves, once the papacy returned to Rome. Leaving its domination by French aristocrats behind, the papacy could once again become the plaything of Italian aristocrats, who vied to place members of their own families in the post for a time. They were popes who worked assiduously to help their own nephews rise and advance in society. Nearly all the major cities that Bávlos visited, including Pisa, Firenze, Lucca, and Siena, produced popes at one time or another, and it was only in the latter half of the twentieth century that non-Italian popes began to reemerge as a possibility. Since the days of Avignon, however, there has never been another French pope.

Many things that Bávlos saw in Italy still exist today. The village of Vernazza where Bávlos swam ashore on Christmas eve 1347 remains preserved as one of the five Cinque Terre, scenic coastal villages that are widely visited by tourists today. Bávlos's time there is chronicled in Chapter 39. You can follow the same path that Bávlos and Maddalena took up to the village of Corniglia: it is well worth the hike.

You can also still find the bust of St. Fina at the collegiate church of San Gimignano, where it remains a treasured relic, just as it was when Bávlos first saw it in Chapter 46. Her blonde hair and smiling face look remarkably like depictions of Catharina Ulf’s Daughter, and it is easy to understand how Bávlos confused the two, particularly given her name, which means “Fine one” in Swedish. The walls of the church in San Gimignano still display the frescoes that helped Bávlos understand the sufferings of Christ, just as the frescoes at Assisi still tell the story of the life of St. Francis, despite the passage of centuries and occasional devastating earthquakes.

At Lucca, you can still see the Crucifix that tradition says was carved by Nicodemus, thus representing a perfect depiction of the Savior’s face. It has been credited with many miracles, and it is seldom that a truly holy person leaves its presence without at least one direct communication from the Savior. Bávlos had an important conversation with the cross in Chapter 51. The city of Lucca still treasures the body of St. Zita as well, now somewhat worse for wear after seven centuries of display at the church of San Frediano, but nonetheless remarkably well preserved for a body of that age.

In Florence, Brother Bartolomeo’s painting of the Virgin remains on display in the church of the Servite order, now known as the Church of the Most Holy Immaculate Conception in honor of the painting which Bávlos heard about in Chapter 49. You can still admire the face painted by an angel, although centuries of retouching makes it difficult to know exactly what the original looked like. Nonetheless, Michelangelo is said to have affirmed that the portrait could not have been done by human hands, and brides of the city still bring their wedding bouquets to lay before the painting in hopes of a blessing from the Virgin.

And even on a quiet road high on the slopes of Mount Morello you can find the little chapel of San Bartolomeo where an unnamed artist painted a saint with a pig centuries ago.

To the north, in the land of France, the papacy continued to flourish for a time. Pope Clement VI continued as supreme pontiff for another three years, living a luxurious lifestyle that earned him the title “the Magnificent.” During this time, he drafted the able cleric Guillaume de Chanac to become an official at Avignon, a position that Guillaume relished thereafter. Bávlos met Guillaume in Chapter 35, introducing him to the art of skiing as they traveled south. The pope was also able to raise his young nephew Roger de Beaufort to the status of cardinal, elevating him to the office at the age of nineteen, even before the young man had received holy orders, the sacrament that transforms a man into a priest. These events happened only shortly after Bávlos met Roger in Chapter 36. Guillaume and Roger together convinced Pope Clement to decorate one of the rooms of the papal palace with images of traditional hunting and fishing, perhaps in memory of Bávlos, and perhaps in honor of the reindeer gift which Clement never beheld with his own eyes. The room today is known as the Cambre du Cerf, the “Room of the Deer.”

Roger the younger was eventually able to travel to Italy, which he thoroughly enjoyed as a land of learning and culture. He studied at Bologna, following in the footsteps of Master Simone and many other great intellectuals of the era. In 1370, he received holy orders, the title of bishop, and the office of pope, all over the space of one week. He took the name Gregory XI, and remained in Avignon until the year before his death. Then, in January 1377, moved by the entreaties of St. Catharina of Siena and Saint Birgitta, he traveled to Italy once again, where he eventually died a year and two months later, in March 1378.

Also in the north, the war that Bávlos heard about from his friend Jacques le Piquant continued to rage for another hundred years. It was only in the 1420s that the tide turned for the French and they were able to begin to push the English back from the fertile soil of France to the sodden shores of their island home. That victory occurred through the visions and work of one of Jacques’s descendents, a young Jeanne D’Arc (1412-31), known in English as Joan of Arc. During her childhood she spent every Saturday at prayer in the very church that Bávlos prayed in when leaving his friend to recover from his ergot poisoning, the Chapel of Bermont. Bávlos's time with Jacques ended there, in Chapter 33. It was in that chapel that Jeanne first heard the voices of Saints Catherine and Margaret, as well as the holy Archangel Michael, urging her to fight for the right of France. Folk called her La Pucelle—The Maiden—a French translation of the name which by which Bávlos knew his reindeer, Nieiddash.

Still farther north, the grand cathedral of Köln remained unfinished for centuries, just as it was in Chapter 27, when Bávlos hurriedly left it behind. Master Gerhard’s hubris and obsession, it was said, were punished in this way, and it was not until 1880 that the great tower of the cathedral was finally completed. For centuries, the lonely crane that the master had installed to erect his tower remained a part of the city’s skyline, a lasting reproach of the builder’s arrogance. Today the Cathedral at Köln, Cologne, is one of the largest cathedrals in the world, and it still proudly displays the massive reliquary of the Three Kings, a masterpiece of art and of history, housing, it is said, the relics of the holy kings that had been confiscated from Milan centuries before.

In Sweden during the same year 1348, King Magnus undertook the crusade against the Orthodox of the Novgorod Empire that he had planned at Birgitta’s urging. Bávlos heard a little about these events during his audience with the king at Vadstena in Chapter 15. The Swedes met with some success at first, but deaths from the Plague soon decimated the troops on both sides, and the king had to withdraw without victory. He eventually made Bengt Algotsson his Marshall of Finland, a title that delighted Bengt but that aroused great envy from among Magnus’s court, particularly because the appointment seemed to carry with it great wealth but little or no real responsibilities. Birgitta was quite critical of Magnus after the war and she never liked Bengt or Blanche very much.

Magnus and Queen Blanche, for their parts, continued to rule Sweden and Norway without too much concern for the disapproval of the Lady Birgitta, who, after all, left for Rome soon after. Out of sight, out of mind, as they say. Magnus and Blanche eventually gave Sweden, Skĺne, and Finland to their son Eric, and Norway to their son Hĺkon, hoping to prevent fraternal conflicts in the future. When Eric and his bride died in bed in 1359, rumors spread that they had been poisoned by Blanche, but modern scholars attribute the death to a reoccurrence of the Plague. Blanche maintained her close relations to her uncle Robert III of Artois, who had helped convince King Edward of England to fight for control of France. Her brothers took turns at being dukes of Namur, all loyal to England and disdainful of France and its crowned ruler.

The churches of Gotland that Bávlos saw in Chapters 17 and 18 were largely destroyed in the Reformation, but those of Reval (modern Tallinn), that Bávlos visited in Chapter 20 remain intact. You will find no statue there, however, like the one which Bávlos delivered. You will find such a sculpture, however, in a museum in Stockholm, where it was deposited after the parishioners of a church in Smĺland tired of it. There, in the antiseptic air and cold lighting of a modern museum, the loving Virgin still turns her bounteous nipple to her divine son, an image of motherly love and religious inspiration that can embarrass prudish viewers even today.

In Finland, a crestfallen Bishop Hemming soon returned to Turku without having accomplished any of the good the Lady Birgitta had intended with her letters. Bávlos met the bishop several times during his effort to acquaint the world of Birgitta's vision, Chapters 11, 12, and 34. Neither the king of France nor even the King of England cared much for Birgitta’s plan for patching things up in the next generation with an arranged marriage between an English prince and a French princess. And due to the onset of the Plague, Hemming was not granted an audience with the pope at all. Meanwhile, on a more local level, the church at Hattula, which Bávlos visited in Chapter 9, eventually received its relic of the True Cross and became a major pilgrimage site. The church was rebuilt in brick and decorated with a remarkable series of paintings. But the older wooden statues of the earlier church were preserved and reinstalled, and there you can still see the Madonna that so inspired Bávlos. Church authorities praised Bishop Hemming both during his life and especially after his death, and they even tried to advance his cause for sainthood, but the Reformation intervened, and the process was abandoned. The cathedral at Turku/Ĺbo remains a monument to the bishop’s grand vision and ambition, and still houses his unsanctified relics.

Far, far to the north, you can still find the great Lake Ánar (known in Finnish as Inari) and the mountains, forests, and rivers of Bávlos’s family home. Sállevárri, the mountain that Bávlos and his family lived alongside in Chapter 2, still rises above the landscape, and Sállejávri still gives its waters to the river Sállejohka. Much of the land in the district remains in a natural state, preserved as a national park and named for the mountain Sállevárri, in Finnish Saalivaara. There, Sámi people still live and prosper on the lands that have belonged to them since time immemorial, although hikers and fishermen come from many other parts of the world as well during the summer to partake of the beauty and peace of the land. Even amid its thriving tourism, Saalivaara remains one of the most sparsely populated regions in all of Europe, crossed by herds of reindeer that represent distant relatives of the lovely two-year old female that Buonamico Buffalmacco painted in his fresco so many centuries ago: a female reindeer who has recently dropped her antlers, a sign that she has calved.