Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348

a free multimedia novel by

Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison

|

Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348 a free multimedia novel by Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison |

|

|

|

|  |

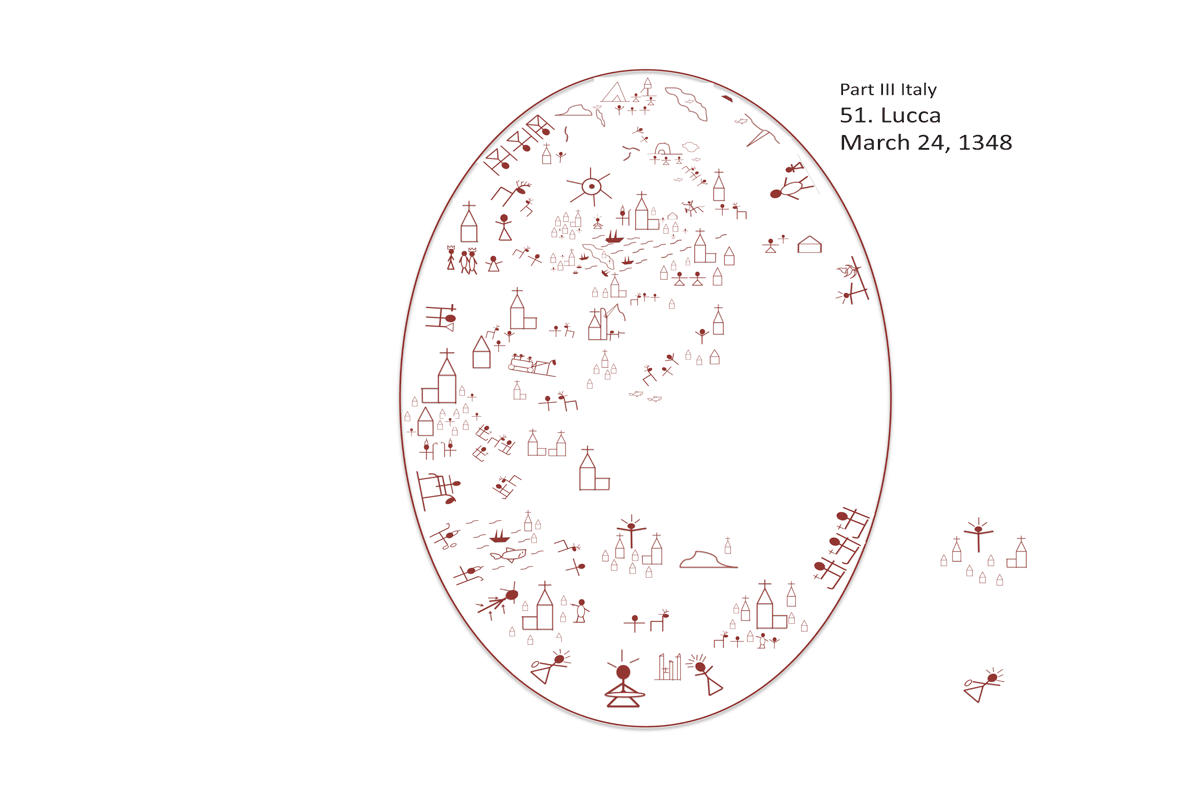

51. Lucca [March 24, 1348]

After this, Joseph of Arimathea, secretly a disciple of Jesus for fear of the Jews, asked Pilate if he could remove the body of Jesus. And Pilate permitted it. So he came and took his body. Nicodemus, the one who had first come to him at night, also came bringing a mixture of myrrh and aloes weighing about one hundred pounds. They took the body of Jesus and bound it with burial cloths along with the spices, according to the Jewish burial custom.

“What did Iesh look like?” Bávlos asked, trying to sound nonchalant. Ever since San Gimignano, he had become more and more interested in getting to know this Iesh personally, and part of that involved fixing an image of him in his mind. The Crucifixes and paintings all showed variations, although they seemed to agree in portraying the Savior as fairly tall, with dark hair and an ample beard.

“You know, boy, that is a question we painters have been working on for some time,” came Buonamico’s chuckling reply. “I should think he looked quite like me, except a good deal thinner. He fasted himself nearly to death there at the end.”

“Hmn,” said Bávlos. “But that’s the problem: you artists always want to make the Savior look like the way you people look here in Italy. And I want to know what he looked like in Gerusalemme.”

“Well,” said Buonamico, “then you need to go to Lucca. They have a crucifix there that was carved by Nicodemo, one of the men who took Christ down from the very cross itself. An angel guided his hand, my boy, and that image is as close to a mirror to the Savior’s visage as ever you will find!”

“A mirror to his visage,” said Bávlos. That was what he needed. “But how did such a wonder end up here in Italy?” he asked.

“How in Italy, my boy? Have you never heard the saying, ‘All roads lead to Rome?’”

Bávlos shook his head.

“Well,” said the painter, sounding a little exasperated,“ It happened like this. Right after the Crucifixion and for a few centuries in fact, the faith was illegal. It wasn’t till the Holy Emperor Constantino that the church could come out of hiding. And when it did, the people back in Gerusalemme who had preserved this cross by Nicodemo, they brought it to the shore of the sea and threw it in!”

“Why’d they do that?” asked Bávlos.

“Well, I’m not sure,” said Buonamico, “Maybe to keep it from the Saracens. Anyway, it floated across the whole sea, by Saracens and Genoans and all the rest, and washed ashore hereabouts. And the holy bishop in whose district it was discovered, he thought up a way to find it a home. He got folk to harness a wagon to the most unmanageable pair of oxen that ever had lived, and they piled the cross on the wagon. And then they slapped the beasts on the behind and off they charged! They didn’t stop till they reached the city of Lucca, and there they humbly came to a stop. So people knew that the cross belonged in Lucca, and there it has been ever since. I wonder you’ve never heard of it, my boy: it’s known throughout the world!”

Bávlos shrugged his shoulders. There was little point in explaining to Buonamico how little he had ever heard of Italy when he lived on his family’s lands. Buonamico would not be able to fathom a land where the fame of Italy was not a topic of daily discussion. Bávlos knew all too well, though, that he hadn’t known anything of any of these cities, not even of Rome, before Iesh had summoned him. So why should he know of a cross in Lucca even if, like St. Henrik’s body back in Turku, it had reached its resting spot through the miraculous assistance of oxen? But now Lucca promised to answer his questions.

“Lohka,” thought Bávlos, considering the word in Sámi, “'It tells.' Perhaps that’s why it has the name it has: it was meant to tell me what I need to know.”

In a matter of days, Bávlos made ready to take his leave of Buonamico. He left Nieiddash in Buonamico’s stable and set out for the city alone. She was sluggish now and wanted rest. The calf should arrive in about a month or so. Walking briskly alone, it took Bávlos just over two days to reach his destination. Like other Tuscan cities, Lucca was surrounded by a wall, but unlike San Gimignano it was not stuck up on a hill. Bávlos’s cockle shell, atop the simple tunic he had received as Buonamico’s apprentice, made him an inconspicuous traveler, and he passed into the city without difficulty. After some wandering, he found the church of San Frediano, close to the wall at the top of the town. The church held many wondrous items: a baptismal font that looked like it had been carved by Northmen and a mosaic painting of Christ high up on its outside wall that sparkled in the April sunlight.

Inside the church, Bávlos also found a woman lying upon an altar to the side of the main nave. Other people were coming up to kneel beside her, touching kerchiefs to her hands. Bávlos drew closer to see what was going on.“Who is this woman who is sleeping in this church and why do these people keep poking her?” he asked an older man. He could see that the woman was middle-aged and rather plain, although she had some fresh flowers woven into her hair.

“That is Zita,” said the old man, “To us she is a saint. She has been dead now for seventy years.” Bávlos looked closely at the woman. Although she lay very still, there was little to indicate that she was not simply asleep.

“But how is it that she is not, not…”

“Not rotted, friend? Yes, she is like fine prosciutto: she only gets better with time. The bishop has said that we cannot yet pray to her, but she has already done many miracles hereabouts. There is not a family in Lucca that does not owe thanks to this woman.”

“How did she die?” asked Bávlos.“She died quietly, of old age,” said the man. One could see that in her face: she had simply fallen asleep, never to awaken again.

“Was she a queen or a noblewoman?”asked Bávlos. In his experience so far, women saints tended to be one or the other.

“No, quite the contrary,” said the old man, “that is why she is so helpful. Zita was a servant. The family she worked for, the Fatinelli, are still in town: you can talk to the children of the family that she cared for, now all much older than I.”

“And she is, or was, helpful?”

“Always helpful, always helpful. And her masters, they didn’t like it. They ridiculed her for her praying and her helping and her kindness. One time she stole some bread from their cupboard to give to a family in need—”

“She stole from them?” Bávlos had not heard of saints stealing before. If a servant girl, a pika, was caught stealing at a Sámi home, she would get quite a beating. Bávlos had heard instances of it among rich Sámi far to the south.

“Yes,” said the older man directly, “She stole. She took bread the family didn’t need and gave it to people who were starving. And do you know what happened?”

“What?” said Bávlos, intensely interested.

“The family got wind of it. The man of the house chased after her and found her bustling along with something wrapped up in her apron.

‘What’ve you got there, Zita’ the nobleman asked.

‘Nothing,’ says she, ‘just some flowers, that’s all.’

‘Flowers,’ says the man, ‘Don’t you mean bread?’

‘No, just flowers,’ said the saint.

‘Well, how about you show them to me,’ says the nobleman. He was fixing now to have Zita flogged both for stealing and for lying. So our Zita, she reluctantly lets her apron fall open and looks up at the sky. And do you know what happened?” asked the man.

“What?!” cried Bávlos, now entranced by the story. The man reminded him of his father.

“Well, out tumbled flowers. Long yellow daffodils, a whole bouquet of them, and roses too! The nobleman couldn’t do anything to her—they weren’t from his garden these flowers and he had no proof that she had done anything wrong at all!”

“So God turned the bread into flowers to help hide the truth?” asked Bávlos. “But wasn’t stealing wrong?”

“Sure stealing is wrong,” said the man, “but some other things are even wronger. Those Fatinelli, they didn’t need the bread. They could afford to help the poor but they didn’t care to. Zita was doing them a favor sharing their wealth a little with the less fortunate. You know what the Good Lord says: ‘Whatsoever you do to the least of my brethren, that you do unto me.”

Bávlos lingered by the body of Zita for some time, watching people come and go, watching her serene slumber. It seemed to him that there was an odor about her that was sweet, like honey, or flowers. At last it occurred to him that he had come to Lucca for another reason, so he slowly stepped away, bowing respectfully and being careful not to turn his back.

Back out in the city, Bávlos made his way to the great cathedral, the Church of St. Martino. There he saw a carved Martino on the wall above the door to the church: a soldier he was, with a sword. He seemed to be cutting his cloak in front of an old naked man. It seemed a taunting thing to do: to cut up his cloak like that just because he could, while the other man had nothing. But a local citizen put him straight about the story: St. Martino had cut his cloak in half so that he could share it with the poor man. They each took half. So Martino was like Zita as well. Their acts seemed like what happened at the winter encampment back home. Families that had good hunters and strong luck shared with those who didn’t so that all could survive the winter. Without that kind of assistance there would have been far fewer Sámi in the locale. To not share would be unthinkable: it would dishonor the luck that one had received, and then Sieidi might decide to direct it elsewhere in the future.

Inside the church, in a place of honor, Bávlos soon found the crucifix called the Volto Santo. On a tall piece of wood hung the image of Christ as Nicodemo had seen him. The follower had gone home after the burial of Iesh, gotten out a piece of wood, and carved this image up. It reminded Bávlos of the way his father would carve things by the fire: memories of the day. But here now was the portrait: Iesh as he died. His hair was long and chestnut colored, neatly parted on the top. He had a long mustache and a rather large beard that started under his chin rather than on his cheeks. Most notably, he was wearing what looked like a gakti, a Sámi tunic, with a long cord belt like monks wear. It was like he was a Sámi who had come to dress as a monk. What was most noticeable about him, though, was that his eyes were round and open: this was not a sleeping Iesh, like on so many crucifixes. He was wide awake and staring straight at Bávlos.

“Buore beaivi,” said Bávlos without thinking, “Good day.”

“Ipmel atti,” answered the face in the Sámi manner, “May God grant it so.”

“So you are Sámi,” said Bávlos, excited. “You and I are brothers, Bávlos. I called you here to me.”

“But why did you call me?” asked Bávlos, now animated. People around him were staring, as this stranger seemed to be talking at the Volto Santo in a language none could fathom. A number of people murmured something to each other and sidled away.

“I need you to help someone in the place called Stop” said Iesh.

“Bisan,” said Bávlos. “I am to help someone in Pisa. I have started to work for Buonamico: is that the help you intended?”

“The help you must give is not yet needed,” said the sculpture, “but the time will come, rest assured. Now, however, I have another task for you. You must learn of Francesco my servant.”

“Francesco,” said Bávlos. “I shall.”