Part III. Italy

Chapter 51. Lucca [March 24, 1348]

Cultural Explanations

|

Part III. Italy Chapter 51. Lucca [March 24, 1348] Cultural Explanations |

|

|

In this chapter speaks to an image of Christ at Lucca, and hears about St. Zita, who stole for the poor. | ||

| Lucca, Volto Santo, St. Zita |

In this chapter, Bávlos travels to the city of Lucca to visit one of the most revered relics of medieval Italy, the Volto Santo, or "holy face." This wooden crucifix was believed to have been carved by St. Nicodemus, immediately after the Crucifixion. Bávlos hears the tale of its miraculous arrival in Lucca, and subsequently speaks to the statue in Sámi. At the church of San Frediano, Bávlos also views the remains of St. Zita, one of medieval Italy's many surviving "incorruptible bodies." Bávlos hears about St. Zita's stealing for the poor and wonders about the ethics of sin and righteousness.

|

|

| Lucca is one of Italy's most genteel and picturesque cities, with a beautifully preserved medieval center, still ringed by its ancient walls. | The city's most recent walls serve as a kind of raised garden for the city, and make a handy way to get from one part of the center to another. |

In 1348, Lucca was still an independent city, not yet subsumed into the growing power of Florence. It had emerged from Pisan domination at the beginning of the century and remained fiercely proud of its unique trade and culture.

|

|

Lucca's oldest church is San Frediano, which preserves a marvelous outdoor mosaic that shows Byzantine influence. |

San Frediano is the resting place of the remains of St. Zita, one of Italy's "incorruptible" bodies. |

The church of San Frediano is named for the city's patron saint and was the first resting place of the Volto Santo. Today the statue resides instead in the cathedral of San Martino, but the relics of St. Zita (1212-72) remain on display. Medieval accounts state that St. Zita's body remained fresh and lifelike for many decades after her death. Today, more than 700 years later, her remains are a little worse for the wear, but still remain remarkably well preserved for their age. It is still customary to bring bread to her relics for a blessing on her feast day, April 27. In 1348, her cult had not yet been accepted, however, and her body was eventually buried, only to be exhumed in the late sixteenth century and again elevated for display. She was canonized in 1696.

|

|

Il Volto Santo |

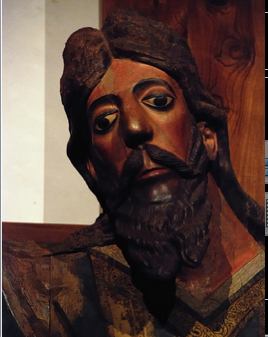

The open-eyed stare of the Holy Face |

Medieval pilgrims flocked to il Volto Santo through the centuries, and the crucifix eventually acquired an elaborate gold and jewel ornamentation which is displayed for the public only once a year, September 13, the eve of the Feast of the Triumph of the Holy Cross. Art historians are dubious about the idea that an observant Jew, such as Nicodemus, would have engaged in making a graven image during his moment of grief after Christ's Crucifixion, and have instead suggested an early medieval dating for the magnificent sculpture. The presentation of Christ in a priest's tunic (which Bávlos interprets as Sámi clothing) and with open eyes renders the sculpture more symbolic than mimetic and ties it to Byzantine art traditions. The forked beard has been connected with Byzantine crosses of the period as well as with the famed Shroud of Turin.

|

|

| Medieval painting of arrival of the Volto Santo | Restored medieval copy of the Volto Santo, housed in the city of Sansepolcro |

The basilica of San Frediano still houses an important painting that depicts the miraculous arrival of the statue, complete with oxen and wagon. It is noteworthy that the Christ in the image is pale in comparison with the modern-day patina of the Volto Santo: centuries of candle smoke have had their effect on the wooden sculpture. Other contemporaneous sculptures, such as the medieval copy of the sculpture conserved in the city of Sansepolcro, have undergone restorations that help us see what the statue probably looked like in Bávlos's day.

Confusion about the image's sweet face and unsual garb led to legends that the statue--or copies of it that were brought north into France and Germany by pilgrims and clergy--actually represents a woman who was divinely granted a beard so that she could repel suitors and carry out her vow to remain a holy virgin. Her father, enraged at her stunt, elected to crucify her as a punishment for her disobedience. Celebrated as St. Kümmernis, St. Wilgefortis, St. Liberata, St. Uncumber, or St. Débarras, this legendary saint represents an interesting side-product of the Volto Santo's international fame.

|

|

LVolto Santo |

St Martin |

In the fourteenth century, the Volto Santo had already been moved to Lucca's magificent cathedral of San Martino. The cathedral's facade represents a strange adjustment to the addition of a tower: one of the three doorways is reduced in size to make room. The statue of St. Martin cutting his cloak remains on the outside of the cathedral, where it can greet pilgrims approaching the church for the first time.

September 13 remains a red-letter day in Lucca, with the celebration of a luminara and nighttime procession in honor of the Volto Santo. All day long, city workers deck the buildings of the downtown with candles, so that by evening the city is aglow in candlelight. At that point, the city's various religious and civic organizations parade from San Frediano to San Martino to commemorate the city's greatest treasure and its civic identity.

|

|

|

| City workers installing candles | Jewelry store readied for the night | Crowds massing in anticipation of the evening |

|

|

|

| Dusk approaching | Nightfall and the procession begins |