Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348

a free multimedia novel by

Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison

|

Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348 a free multimedia novel by Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison |

|

|

|

|  |

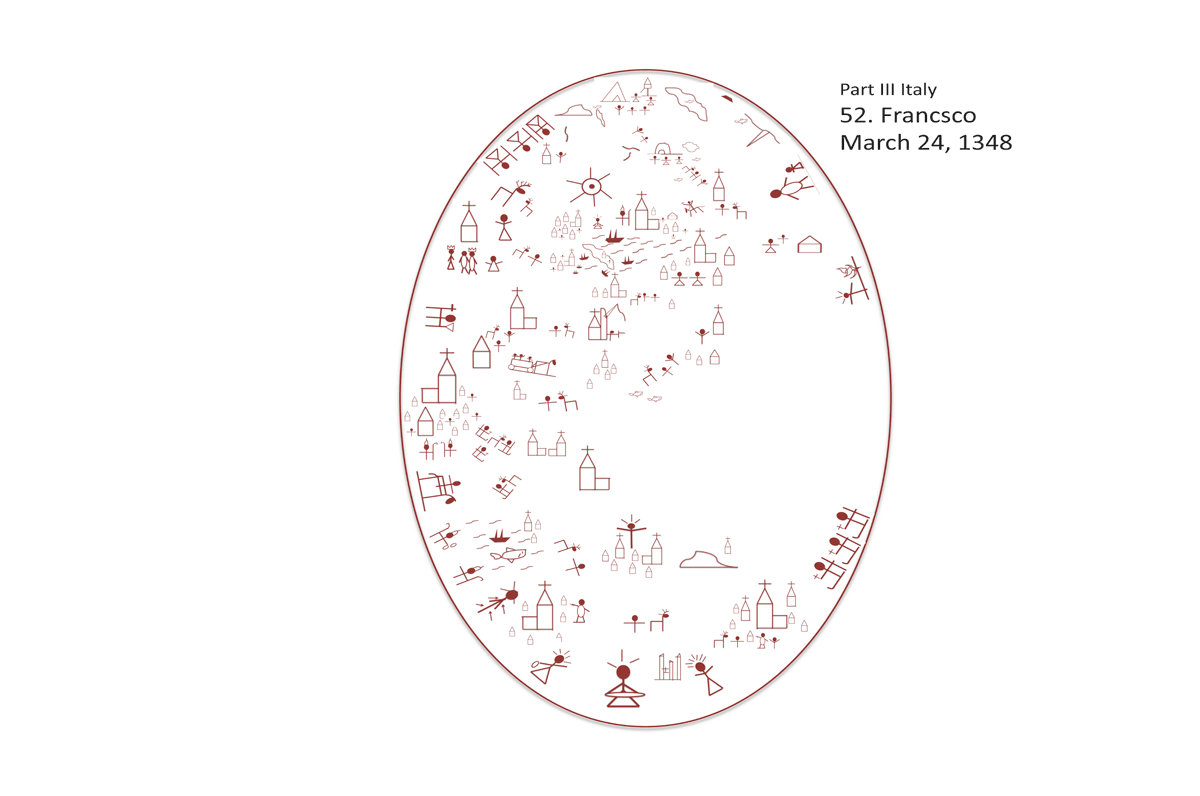

52. Francesco [March 24, 1348]

For the cult idols of the nations are nothing, wood cut from the forest, wrought by craftsmen with the adze, adorned with silver and gold.

Bávlos prayed deeply in the church before the Volto Santo. At last Iesh seemed to be communicating openly with him again, and it seemed to Bávlos that his task was fast approaching. Somehow it had to do with Buonamico and the city of Pisa and the holy San Francesco. Just how these things all fit together remained a mystery, but they seemed to be coming together in a very methodical and significant manner.

Bávlos went out to sit in the sun. His head was swimming with thoughts. At the far end of the square, a monk had climbed atop a pulpit and was beginning to preach. Bávlos walked near to listen. The little monk was warm and jovial-looking: bald, with a large hooked nose and fat little arms. He wore a habit of coarse brown, tied with a white cord.

“And when he arrived at the house of the official, he noticed the commotion that was going on, people weeping and wailing loudly.‘What’s all this fuss about?” he cried. ‘The child is not dead but asleep.’ “They ridiculed him. So he ordered them all to leave. He had the child’s father and mother stay, along with his disciples. He took the child by the hand and said in his language ‘Talitta kouma,’ which means ‘Little girl, I say, Arise!’

“No it doesn’t mean that at all,” thought Bávlos. He couldn’t say for certain what the words meant, but it was plain that they were in Sámi. After some puzzling, it occurred to him that Iesh had said ‘Dá lahttu golbma’: ‘here are three limbs.’”

Meanwhile, the preacher was continuing his story. “So the Holy St. Mark tells us in his Gospel. Christ can snatch the sick from the very jaws of death. So he did with the little girl, so he can do with each of us. We must let Christ save us from the death that awaits all sinful people, a death of unending torture, a death of burning fire. We must respond to Christ when he says to us ‘Talitta kouma.’”

Aside from the man’s poor skills in Iesh’s language, Bávlos found this man’s words most compelling. There was something simple and direct about him, and the story he told of Iesh’s healing was very familiar sounding. Iesh must have taken the little girl’s hand in his, blown upon it and said, “Now there are three limbs,” meaning that he was there to help pull her back. And she had returned, come back from the edge of death. It was the touch, and the breath, and the words that had done it, performed by one with healing powers. Iesh could make the dead come back to life, in the case of the little girl, even as he could make the dead seem alive eternally in the case of the elderly Zita. Death seemed no match for Iesh. And furthermore, Iesh had shared this gift with the family of the girl, even though they were not kin. He had not kept his powers to himself but reached out to them in their need and given something that belonged to him so that they would be better off.

After the preacher had finished his sermon, Bávlos pushed forward to talk to the monk. The man seemed pleased to see him. “Kind sir,” said Bávlos. “You seem to know much of our Savior and his ways. Can you also tell me of Francesco?”

“Of Francesco?” laughed the man, “Of Francesco? Of course! I am a Franciscan myself!” Bávlos soon found himself in the company of a small collection of monks dressed the same as the little man. They had scraped together a meal, mostly from things they had received from others, and were glad to welcome one more into their circle. While they ate, they shared stories of Francesco their leader.

“Tell him about how Francesco gave up his father’s wealth!” said one man, a tall thin monk who seemed to be the oldest of the group.

“Yes,” said he little friar, whose name, Bávlos had learned, was Brother Felix, “that was a crucial moment. Our friend Francesco was born to a wealthy family: cloth merchants. Big house in town, lots of servants, the works! But when Francesco heard the call he left all that entirely. Even the very clothes on his back—he peeled those all off and gave them to his father. ‘I used to call you my father on earth,’ said Francesco. ‘Now I shall only say Pater noster qui es in caelis!’”

“He took off all his clothes?!” asked Bávlos in amazement. He thought it a little easier to imagine this kind of thing down here in a warm country. Down here one could imagine going about without any clothes on pretty easily, whereas back home survival would be difficult without something warm to wear in the winter. It seemed somehow reckless of Francesco; perhaps that was the point. He thought for a moment and then asked, “So how long did he go about without any clothes?”

The other men laughed. “Why no time at all, of course,” said Felix jovially, “People gave him clothes to take the place of the ones he gave up! Not great clothes, of course: they gave him worn out things they no longer wanted. But he was grateful for them because they came from God.”

“They came from God?”

“Yes,” said Felix, “from God. When you give things to others as a kindness, then they come from God.”

“Hmn,” said Bávlos nodding. He did not actually understand at all what these men were saying, but they seemed so certain in their assertions that he felt embarrassed to press the question any further. How could something a person does be mistaken for something that Iesh is doing? If the clothes were from other people then they were from other people; if they were from Iesh, then they were from Iesh. Obviously, if the clothes were worn-out and used, they were from people: Iesh wouldn’t have any need to give used things. The whole thing could only made sense if Iesh somehow had decided to act through the actions of others: had chosen to give to the poor through Zita’s taking the bread, or to give clothes to the poor man through Martino’s cutting the cloak, or to give these men dinner through people donating things to them. For some reason Iesh chose to use proxies; he expected others to act on his behalf. And come to think of it, had not Iesh called him down to this land to do some work for him? Was he not also soon to become a tool of Iesh? “Tell me more stories of Francesco,” said Bávlos. “He seems a wondrous man.”

Nothing seemed to please the men more than to comply. “Let me tell you about the water!” said the old thin monk, whose name, it turned out, was Mario.

“Yes, do, tell him that one!” said Felix, happy to pass the responsibility of storyteller on to his elder.

“Well,” said the older monk, drawing himself up and squinting a little as he began his story, “Francesco was riding along one day and he came upon a poor thirsty man. The man had no water to drink and it was blazing hot out. He looked like he was going to die from the heat and dryness of it all. So Francesco gets down from his horse and prays to God. Then he says to the man, ‘Go over to that rock and see if there is anything to drink there.’ Sure enough, a spring had started. The man drank his fill and the spring continues to flow today.” All the men in the little group murmured in recognition and delight at the tale, even though, Bávlos reckoned, they must have heard the story many times before. These men seemed to like to retell stories about Francesco in the same way that folk back home liked to tell stories of his grandfather Sálle and the great things he had done. It didn’t matter that the stories were familiar to everyone. What mattered was that Francesco had been a man of power, like Grandfather Sálle, and that his help was still available to folk like these men in the same way that Sálle was available to Bávlos in his thoughts. It was notable that Francesco seemed able to give Iesh orders, making him produce water where there had only been rock before. Or perhaps “orders” was not the right word: it seemed like Francesco had made good requests, that Iesh chose to grant. Iesh not only seemed to want to act through other people, he also seemed to want to let them decide what he would do.

A younger one of the brothers spoke up, a shorter friar with dark curly hair named Giovanni. “I like the story about Francesco and the birds!” he said. The other men nodded in agreement.

“The birds?” asked Bávlos. Now this was sounding more Sámi.

“Yes,” said the young brother. “Francesco used to preach to the birds! One day he saw them in the trees and called them down. They lined up in front of him and he preached them a sermon!” Bávlos found this piece of information very interesting.

“Yes,” he said, “and what did he tell them?”

“Why, he told them to be happy and praise God for their feathers and ability to fly and the air in which to do it!”

“Hmn,” thought Bávlos. These are things birds are usually happy about already, even without Francesco’s exhortation, so his preaching probably did little good. The fact that he was talking to birds, though, was significant: it showed that he knew something about Sámi ways, if only through Iesh. “I wonder what he really talked to them about?” thought Bávlos; “probably something that he didn’t want his followers to know. Maybe they were telling him about conditions elsewhere, or maybe he was using them to communicate with allies far away.” Aloud he asked: “And then what happened?”

“Why he made the sign of the cross over them and dismissed them. And they flew off in four squares, tracing the image of the cross in the sky.”

“Hmn,” said Bávlos. So that was it. He must have given the birds instructions to carry out and they did so, dividing into four to approach the different quadrants of the world. Francesco was sounding very much like a noaide now. “Did he ever talk to any other animals?”

“Did he?” cried Felix, “He talked to a wolf!”

“To a wolf?” said Bávlos. Now things were getting really interesting. Only noaiddit talked to wolves, and when they did, it was a serious affair. “What did he say to a wolf?!”

“Well,” said Felix, “It was like this. A big and very menacing wolf was killing both people and animals in the area about the city of Gubbio.”

“Ah,” said Bávlos. Wolves that attacked humans were often other humans who had transformed. People could change into wolves by circling particular magic trees, and provided they returned to the tree and circled it again in the reverse direction, they could return to their human form. They did it when they were short of food, or when they wanted to steal from others. Alternatively, a noaide might turn a person into a wolf as a punishment, particularly if that person had been stealing reindeer. “So what did Francesco say to it?”

“Well he called the wolf to him, and do you know, the wolf came! And once he was there, Francesco reasoned with him. He said, 'Dear brother Wolf, please, if I guarantee that the people of the town supply you with food, will you leave off attacking them and their beasts?'”

“Ahaa,” thought Bávlos. “So it was a case of a wolf transformation due to hunger.” Aloud he said: “And what did the wolf say?”

“The wolf agreed. It put down its head to say that it agreed with Francesco’s terms! And after that it never bothered the citizens again. They saw it all the time thereafter and they fed it and it never harmed another person again. In fact, they were sorry when it finally died.”

“Of course the wolf agreed,” thought Bávlos. “It had what it needed now.” Still, you had to hand it to Francesco. He must have recognized that this wolf was a hungry person transformed, but rather than call the person out on the act and see that person and his or her family chased away from the region for good, Francesco chose to give the beast what had been lacking in the first place. But then, Bávlos suspected, Francesco must have cut down the person’s changing tree so that it had to stay a wolf forever. Then the wolf had no choice but to to remain near the city in animal form, dependent on the human community for the food it had formerly stolen. But now, rather than being guilty of theft, the wolf became a cause for people to become kind: to share their bread with the poor neighbor who had been so desperate for food that he or she had turned into a wolf. It was an elegant solution to the situation, something worthy of Zita, and for Bávlos, it seemed more than what someone could learn second-hand. No, somehow, it sounded as if this Francesco was Sámi himself.“But you say this Francesco was Italian?”

“Of course,” cried the men. “From one of the finest families in Umbria!”

“Well,” said Bávlos, “I think I would like to go to this Umbria and see where Francesco lived.”