Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348

a free multimedia novel by

Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison

|

Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348 a free multimedia novel by Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison |

|

|

|

|  |

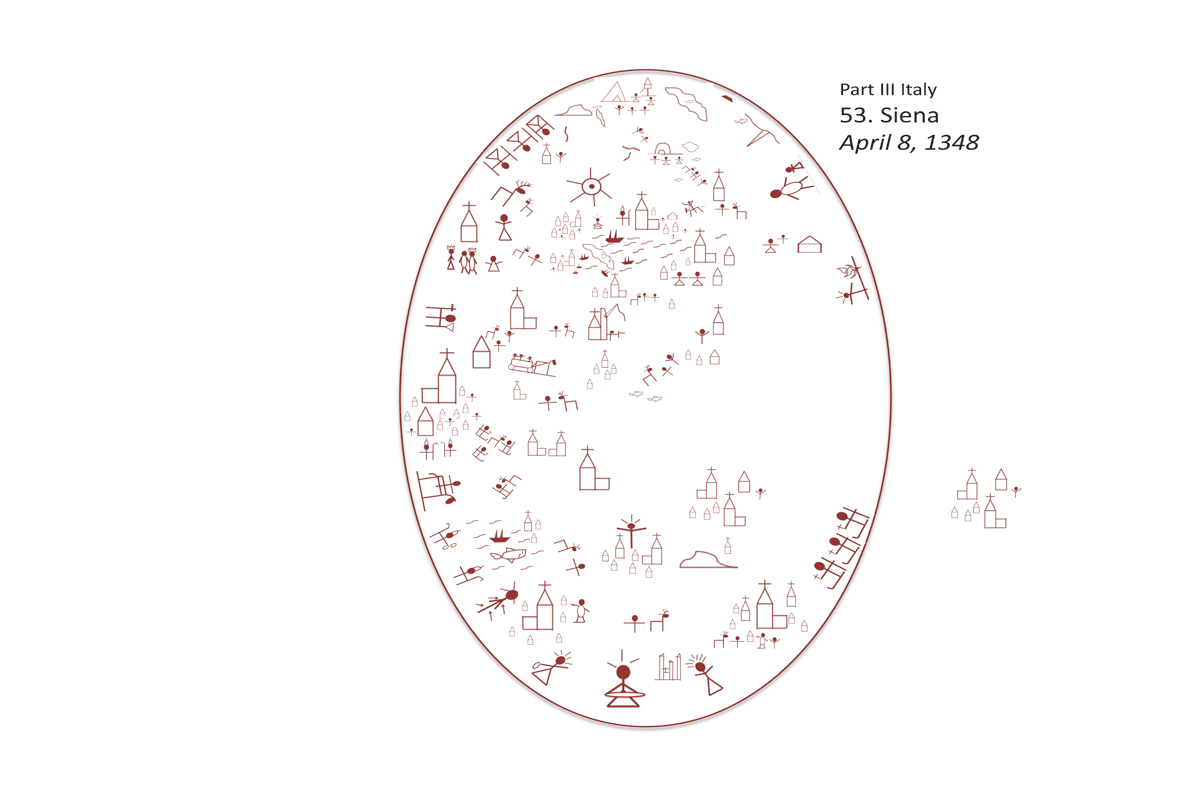

53. Siena [April 8, 1348]

A scribe approached and said to him, “Teacher, I will follow you wherever you go.” Jesus answered him, “Foxes have dens and birds of the sky have nests, but the Son of Man has nowhere to rest his head.”

“Enemy territory, boys,” chuckled Brother Felix, “Keep on your guard.” The small group of Franciscans—Brother Felix, Brother Giovanni, and their new potential novice Brother Bávlos—were passing in front of the sprawling Dominican church of San Domenico, looking to spend the night at their own order’s house on their way to Assisi. They had been walking for two days from Lucca, and they were muddy and tired. Behind them trudged a very heavy-looking reindeer, her head bent low in a sign of exhaustion. Nieiddash needed rest, as did the men.

“Our order has a friend who lives in this neighborhood: a worthy cloth dyer named Giacomo. His wife was expecting her twenty-fifth child when last I was in town, and I would gladly visit with them this evening. In the meantime, though, let us go to our priory and church, say our prayers and have some dinner.”

The band made their way through the city’s winding streets toward the opposite end of town where the church of San Francesco lay. To their right, Bávlos could see a towering cathedral at the highest point of town. Gigantic though it was, it was still not big enough for a city of Siena’s pretensions.

“They’re building it even bigger,” said Brother Giovanni, shaking his head, “What you see now will only be a side corridor! It will be bigger than anything in Rome or in Avignon when it is finished.”

“Pride,” said Brother Felix, “pride. They are tempting God with that project, I tell you, tempting God.” He crossed himself quickly however and added: “Not that I wish any ill on them, not at all! Still, there should be some limits even to the size of one’s church.”

“Hmn,” murmured Bávlos. This tendency toward ostentation was certainly common in this country. Nothing was ever big enough, it seemed. Buildings had to be larger than large, and decorations were heaped on top of other decorations. For a man who came from the quiet world of the far north, Italy was constant sensory overload. Sámi kept their art and their homes simple: just enough artistry and goods to make it pleasant, but also enough rough or open space to keep it honest. He was glad that the Franciscans, at least, were simple at heart. When they arrived at the order’s piazza, however, he found that his new brethren had as great a propensity for overdoing it as other Italians: they were in the midst of constructing their own immense church, nowhere as large as the cathedral, but every bit as grand as the church of the Dominicans.

“Yes, well,” said Brother Felix, reddening a bit, “one cannot be outdone, after all…” The whole issue of wealth and possessions seemed to be a touchy subject among these Franciscans in a way that it had never been among the Dominicans or other monks Bávlos had met in his travels up till now. It seemed like they were yearning to live in a simple manner, like the Sámi, but that they did not quite know how.

“The stable will be fine for me,” said a worried Bávlos. “I think I need to be with Nieiddash tonight.” It is strange how a person can sense when an animal is going to give birth. Nieiddash had a nervous look in her eye and her breathing was short. She seemed intent on being by herself and although she remained warm toward Bávlos, she had turned decidedly skiddish toward the well-meaning Franciscans, even toward the gentle Brother Giovanni. He helped Bávlos muck out a large box stall at one end of the stable and strew it with fresh straw. Then he withdrew to let Bávlos spend the night alone with his charge. Bávlos found a comfortable spot in the corner of the stall and lay down. Nieiddash came up to nudge him once, giving him a playful nip. Soon, however, she was lost in her own thoughts, pacing up and down, her breathing getting faster and her eyes darting to and fro. Reindeer will only circle in one direction, and Bávlos found it amazing that Nieiddash continued her species’ trait even in this alien land. She circled over and over, springing up at times to see if all was safe. It was dark in the stable now, except for Bávlos’s lantern. Back home, it would still be light at this time of night, and Nieiddash would be able to calf with the benefit of watching out for danger. Calving is the moment in a female’s life when they are at their most vulnerable, as wolves and other predators look to attack once the process has begun. Nieiddash would have to trust in her human friend as protection here and trust in the Franciscans’ barn to keep out dogs and dangers. As time went by, Bávlos started to joik. Singing is the one thing that can truly calm a nervous reindeer, and Bávlos started by singing the joik he had composed for Nieiddash.

“Little maiden, swift footed, walking ever on, lo, lo, lo…”

The singing seemed to help, so Bávlos continued with other joiks. He joiked their mountain back home, where the calving would have occurred if Iesh had not summoned them here. He joiked the herd that Nieiddash was from and the meadow in which she was born. He joiked his father and mother and his sister Elle. He joiked the springtime and the river. And he started to think of joiks he should compose about things down here: the Tuscan hills, Buonamico, Fina, Giovanni, Francesco. Bávlos was suddenly pulled from his musings, however, by the reindeer’s signs of distress. She was moving rapidly now but the calf was not coming out right.

“Help her,” said a voice. “She needs your help.” Bávlos recognized the voice of his grandfather.

“How do I help her?” cried Bávlos. “What does she need?”

“In a moment you will see the head of the calf begin to emerge. It must not come first. You must push the head back in and find the calf’s legs. They must come out first.”Bávlos had no experience in this sort of intervention. At first he could not even imagine how he might accomplish what his grandfather was calling for. In his desperation, he called to Iesh:

“Iesh, help me: how am I to do this?”

“Remember the words,” said Iesh.The words. What were those words that Iesh had used when healing the girl? Brother Mario had recited them, but had gotten them wrong. Now Bávlos tried to recall what they were. “Dá lea…’here are’…” the phrase would not come back. Instantly, Bávlos sprang out from the stall and raced toward the friary. The brothers had all gone to sleep. He hammered on the door desperately:

“Brother Felix, Brother Giovanni! Help! I need your help!” It was not long before a window opened above his head. It was a tired looking Brother Felix.

“Bávlos, brother, what is the matter?”

“Brother Felix, I need your help right away!”

“What is it?”

“When Jesus healed the little girl in the house back in Gerusalemme, what words did he say?”

“Oh he says something in his language,” said the friar.

“Yes but what!”

“He says, ‘Little girl get up,’ or something to that effect.”

“No, no, no! What does he say in his own language?”

“Oh my, Bávlos. I don’t recall. You’ll have to wait till morning when we can check in the Bible.”

“No,” cried Bávlos, “I need to know now. It’s important!”

“Talitha koum,” came another voice. A new window had opened one storey above, and the old Brother Mario was poking his head out timidly.

“What was that again?” called Bávlos.

“Talitha koum,” said Mario with authority. “That is what he said.”The words sounded a little different from what they had sounded like when Brother Felix had pronounced them, but enough alike that Bávlos could remember what they meant.

“Yes!” he cried. “Thank you!”He raced back to the stable and into the stall. By this time he could see the tip of the calf’s nose emerging just below Nieiddash’s swinging tail. The little piece of the calf was so dark and sodden with the fluids that were trickling out of Nieiddash’s backside that Bávlos could scarcely make out what part it was. At length, however, he recognized it as a tiny muzzle. He quickly approached Nieiddash and laid his head against her side. Then quietly, firmly, he began to push the young animal’s head back into its mother’s birth canal. As he pushed he said in quiet tones,

“Dá lahttu golbma’: ‘here are three limbs.’ ” He pushed and pushed, holding the calf back against its mother’s straining to expel it, and using her pauses in contraction to slide the calf back into the comparative space of the uterus. His arm was now buried deep inside the animal’s back end, and the walls of her birth canal squeezed his arm like a tourniquet.

“Now find the legs!” came his grandfather’s voice. So this was it. Three legs. He had to find the two legs that, together with his own would make three limbs. Gradually, he figured out what he was feeling: there was the head, with its tiny muzzle and ears, there was the neck, there was the chest, and yes, bent back, yes, here were the legs! Slowly, delicately, he hooked his fingers around them and tried to draw them forward. They were slippery and difficult to maneuver, and they felt as if they were miles long. Nonetheless, after what seemed like an eternity, he found himself holding two tiny hooves. He pulled these outward, toward the birth canal.

As if Nieiddash had been watching the entire process with an inner eye, she now began to push anew. In what seemed like seconds, the hooves had reached the outside air and with another minute of pushing they were dangling down like gangly ribbons, hanging from the mother’s twitching backside. A moment later the head had emerged again and then, almost like an afterthought, the weight of the exposed calf pulled the remaining portions of the little animal down the birth canal and into the world. With a wet flop, the calf and its afterbirth were suddenly upon the ground. The calf was born.

Bávlos stepped back to watch the young mother take over. In an instant, she had severed the umbilical cord, freed the calf from the membrane that surrounded it, and begun to lick it briskly. Within a matter of moments, the calf was on its wobbly spindly legs and beginning to nurse.

“Thank you, Iesh, for the words,” said Bávlos. “Thank you for this miracle.”

“Take some of the milk when the calf is done drinking and set it aside,” came Iesh’s reply.The next morning, when Giovanni poked his head in to see how things were getting along in the stall, he saw a sleeping Bávlos, a standing Nieiddash, and a little, sleeping calf.

“Wonderful!” he breathed. Bávlos opened his eyes.

“Isn’t it?” he whispered. “Nieiddash has become a mother.”

“Come friend,” said Giovanni. Come to morning prayer and then breakfast. This is a day to remember!”

At breakfast, the friars had an animated discussion of the previous night’s events. They were divided on what the Savior’s words meant, but they certainly were in agreement that the birth had succeeded through the mercy of God. And they were full of admiration for Bávlos for having remembered the story and wanting to repeat the Savior’s words. They also were curious about the small ladle of thick milk that Bávlos had brought in with him from the stable.

“A voice told me to collect it,” said Bávlos, “and so I have. Where I come from, the first milk of a reindeer mother is especially good for a new mother and child to drink.”

“Well, I hope we don’t have any new mothers in the house right now!” laughed one of the brothers.

“Wait a minute,” said brother Felix. “I do know of one here in town! It’s that Lapa, wife of the cloth dyer Giacomo di Benincasa. She gave birth a couple of weeks ago. Let’s take the milk to her!”

That very morning, Brother Felix and Giovanni and Bávlos made ready to do just that. They poured the thick milk out of the wooden njalla that Bávlos had made and into an earthenware pot more typical of Italian peasant life. Then they put a lid on it and set out for Giacomo’s home. Before long they came to a pleasant house with a wide loggia and an airy courtyard by the street. They entered the courtyard with cheery smiles, bracing themselves for the greeting of the twenty-odd children that still lived at home. Instead, they found silence. Children sat on the ground in tears. Neighbor women milled about talking in hushed tones. An old woman was sitting by the house’s main door, weeping quietly, beating her chest and shaking her head. Something terrible had happened.

“It’s a pity,” said one of the neighbor women. “Poor Lapa. Twin daughters and now soon,”

“Don’t say it!” interrupted another woman hastily. “Never say it! Just pray!” The courtyard was abuzz in Aves and Paters. After some persistent questioning with a gentle voice, Brother Felix was able to piece together what had happened. The local women were only too happy to recount the tragic tale. Lapa had given birth to twin girls, lovely infants, whom she had named Giovanna and Caterina. They were tiny because they were twins, and because Lapa was not as young and hale as she had been when she gave birth to her oldest daughter Bonaventura so many years ago. Now Bonaventura was a grown woman and married, and still Lapa was giving birth. Because the children needed nourishment, Lapa turned little Giovanna over to the wet nurse she had engaged for the purpose. But in order to feed little Caterina, she had decided to nurse her herself. In fact, this was the first time in all her years that she had ever nursed one of her children herself. The wetnurse was young and healthy, yet somehow Giovanna had not done well. After just two weeks of life, the little child had died, just the day before. And now it looked like Caterina would not last the day either.

“Good friars!” cried a tall, stocky man who had just emerged from the doorway, “Come into my home! Thank you for visiting me on this day!”

“We are sorry for your great loss,” said Felix. “She was baptized, the little one?”

“Yes, thank God,” said the father with a sigh of relief. “She is dead now, but she will come to heaven without a pause.”

“Indeed, said Felix, “She has gone to a better place.”

“But what about the other one?” said Giovanni, rather more impatient. “How is she?”

“She is tiny and struggling,” said the father. “But she has a great will to live. And we are all praying for her.”

“Our brother Paolo here is a healer,” said Giovanni all at once. Bávlos noticed how he had now received not only the status of brother but also an Italian name. And, more worrisome, he noted how Giovanni had rather rashly described him as a healer. Healing was not something one can take for granted: in the Sámi way, healing powers find outlet in people; it is not people who choose how or whether to heal. To call someone a healer was thus to court disaster. Bávlos opened his mouth to disavow the description but at once he felt Giovanni’s hand touch him on his back.“Don’t talk!” said the gesture. “Let us handle this our way!” Bávlos simply nodded, and looked down.

“Yes, yes,” said Felix. “Our brother is a learned healer who has come to us from afar.”

“From Venice?” asked the dyer, his eyes opening wider.

“Even farther, said Felix impressively. “From France!” There was a murmur among the women in the courtyard. They had been listening carefully and now they began to twitter excitedly.

“Paolo has brought you a healing milk,” said Giovanni. “It is a mixture of colostrum and prayer. Let us administer a little to your wife and surviving daughter.”

“Gladly,” said the father. “I am honored that you would come to us in our need.”The three brothers were ushered into the room where Lapa lay, her baby in her arms. After what seemed like an endless chain of discussions, tears, nodding, and crying again, it was agreed that Lapa and little Caterina would each drink a little of the healing milk that Paolo had brought. One of the women brought a small horn such as people used to feed baby livestock when their mothers had died. They poured a little in the horn and gentle opened the infant’s mouth. Then Bávlos spoke. He took the little infant’s tiny hand in his and said in a gentle tone that all could hear, “Dá lahttu golbma’.”

“What’s he saying?” whispered the women to one another at the doorway.

Giovanni turned to them and said, “It’s from the Bible. It’s Christ’s own healing words.” The women nodded reverently.

Nearly a week later, Nieiddash and her calf were anxious to get out into the world. Nieiddash had lost her antlers, which Bávlos was glad to save as a source of materials for carving. He set about making a rendering of the Virgin in the manner of the ivories he had seen in France. Nieiddash seemed excited by the lack of weight on her head, or perhaps by the itchiness of the new black buttons beginning to rise in their place. In her lightheaded state, she wanted to be out in the hills again, running and grazing, showing her calf the way to forage for food. The trail to Assisi would be an ideal trek for her and her calf: It would help her build back her strength and allow her calf to gain strength and swiftness in his legs. Bávlos would likely have to carry the calf for portions of the walk if they were to make the progress they needed to get there without too much delay. The little calf, for its part, was a healthy young male. Giovanni had come up with a name for him: Admirabilis.

The order had decided to order a new set of frescoes depicting the life of San Francesco. These were to be painted by a great painter, but none seemed available. Fear of the Plague was keeping painters from moving and all the Sienese masters were too busy. Bávlos suggested Buonamico.

“Buonamico Buffalmacco?” said Brother Mario, “Do you think we can persuade someone of that fame and worldliness to come to our church?”

“I think so,” said Bávlos. He didn’t let on that the commission would likely be immediately welcomed by his friend, who was perennially short of money and assignments.

“A pity we could not tempt that Brother Bartolomeo of the Servites,” said the elderly Brother Mario.

“No,” sad Bávlos, “I am certain that he would not do it. He has given up painting altogether in honor of the miracle that occurred when he painted the Annunciation.”

“Yes, yes,” muttered Mario, “But it would be a welcome thing if an angel were to do some painting in our church.”

“Well, I’ll admit that Buonamico Buffalmacco is not an angel,” said Bávlos truthfully, “but I have heard Brother Bartolomeo, the very one of whom you spoke, describe him as gifted with such talent that he needed no angel to help him.”

“Well,” cried Brother Felix in exultation, “that sounds plenty good to me!” So it was decided that Brother Mario should travel to Firenze at once to invite the famous painter Buonamico Buffalmacco to their church.

In the meantime, at the home of the cloth dyer, from the moment of receiving the milk from Nieiddash, both Lapa and her child had turned a corner for the better. Giacomo had come to the friary in tears, wringing his hands and kneeling at the doorstep with thanks. All the city was talking of the mysterious French friar who had pulled the little Caterina away from the brink of death. They had heard about his reindeer and there were some that were wondering if he could be the same stranger whose deer and mules had been saved by St. Fina back in San Gimignano. But others thought it couldn’t be: that man was an apprentice to a painter, not a friar, and he had spoken Italian well. Yet how many strangers with deer were likely to be trapsing about Tuscany? Who knows? Perhaps deer had become fashionable as pack animals in France: certainly this friar Paolo had the air of noble upbringing, and when people heard him talk, he certainly did have what sounded like a strong French accent.

Bávlos was glad that he would soon be headed off, to leave all this gossip behind. He wanted more time to talk with Felix and Giovanni too, and the walk seemed an ideal means to learn more. On a morning about a week later, just at the outset of Holy Week, Bávlos came to the house of Giacomo again to pay his respects. The man sprang to his feet when he saw Bávlos approaching and pumped his hand in welcome. He brought him in to see a radiant Lapa and her now thriving child.

“Thank you for your help,” said Lapa looking into his eyes. “Giitu.” Bávlos blinked. Had Lapa just thanked him in Sámi? He wanted to ask, but something in Lapa’s look told him not to: Giacomo looked on and was eagerly asking questions about the healer’s next journey and plans.

“May I hold the child?” asked Bávlos, timidly.

“Of course!” cried Lapa at once. Gently, but with great pride, she placed the little infant in Bávlos’s arms.

“You have done well.” Bávlos was aware that the voice was inside his head, not heard by others.

“Iesh?” he said in the silence of his mind.

“Yes.” Replied the voice.“Was this the work for which I was summoned?” he asked.

“Not only this one,” came the answer. There was a pause. “The child you have saved will do great things, Bávlos. She will serve me well. I am pleased that you shared the milk with her. She will return the favor to many in her life.”Bávlos smiled. He looked into the baby’s eyes. She was looking at him, he thought, not with the senseless eyes of a newborn, but with eyes that know and appraise. She seemed as if she had understood everything that had just been said, even though it had been said in Sámi, and inside his heart alone. A little flustered at this impression, Bávlos handed the infant back to his mother. He raised his eyes to look at her. She was staring straight at him, again, as if she had heard and understood his entire conversation. She gave him a little nod and a crooked smile.

“Go well,” she said to him in Italian.“Stay well,” he replied. Shaking the grateful Giacomo’s hand once more and tossling the hair of six or seven of the children in the doorway, he turned and walked away.