Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348

a free multimedia novel by

Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison

|

Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348 a free multimedia novel by Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison |

|

|

|

|  |

54. The Road To Assisi [April 23, 1348]

Do not take gold or silver or copper for your belts; no sack for the journey, or a second tunic, or sandals, or walking stick.

It was another week before Bávlos and his companions prepared to leave. Easter had come, and Bávlos enjoyed the celebrations that brought an end to the long fasts and deprivations of Lent. By that time, Nieiddash’s antlers were almost the length of her ears and growing well. Admirabilis had taken to frisking about the barnyard, nosing the goats, investigating the hens, darting at the sight of human strangers. Buonamico had arrived and had taken to drawing sketches of the animals. He seemed moved by the tenderness with which Nieiddash prodded and schooled her little offspring.

“Beautiful creatures,” he said, tears welling in his eyes. He had spent an hour observing and sketching the young Admirabilis.

“Beautiful drawings,” said Bávlos, looking over his friend’s shoulder.

“Renderings of creatures, my boy, just renderings of creatures. Not of much interest as art.”

“But you’ve captured somehow the spirit of Nieiddash and her calf,” said Bávlos, admiringly. “I can recognize her exactly in your picture: the way she sniffs the wind, the way she nudges her calf.” To him, Buonamico’s sketches were a kind of a visual joik: a signature of these two animals that any knowing audience member could recognize. “Why is it that you don’t call that ‘good art’?”

“It simply isn’t, Paolo, that’s all. Mark my words: wildlife and domestic beasts will never become the subjects of real art. Saints, my boy, and biblical scenes: nothing will ever displace these as the prime objects of art.”

When he wasn’t observing the reindeer, Buonamico spent most of his time working on the drawings for his planned frescos on the life of San Francesco. Bávlos enjoyed looking at his friend’s sketches for the frescoes and hearing explanations from the brothers as to what the scenes were about. He was particularly struck by one which Buonamico had completed and already frescoed onto the wall. In it, a sleeping Pope Innocent III was dreaming that a great church was toppling, while a devoted San Francesco was holding it up. A lot of space was taken up on the pope. Corpulent and regal, he lay in a tiny house of gold.

Bávlos asked:“Do you suppose the pope really slept in his clothes like that?”

“No of course not, my boy. Artistic license, artistic necessity. You wouldn’t know it was the pope unless you saw him in his robes—his vestments I mean.”

“But he’s even got his hat on,” said Bávlos, frowning. The sleeping pope was lying with a bishop’s miter on his head. It pointed upward over his bright blue pillow and looked like it would get crumpled in the holy man’s sleep.

“Yes, well, perhaps I could have put the hat on a night table instead, but then I would have had to paint a night table, and the whole piece would become cluttered.”

“Is that your face you have used for the pope’s?” asked Bávlos, smirking.

“Indeed, my boy, I needed a distinguished face for the purpose and mine just happened to be around. You couldn’t expect me to use one of these friars as my model, could you? Why, the whole experience would go right to the poor man’s head and he’d want to be called ‘Holy Father’ ever after!”

“Well, Holy Father, I suppose you are immune to such effects. Hey,” said Bávlos, growing perturbed: “Is that my face you’ve used for Francesco’s?” Something inside twinged as Bávlos looked at the image. There he was in a Franciscan habit struggling to hold up a toppling church tower. He found it outrageous that a person of his lowliness and foreignness would be the model for such a holy saint.

“My son,” said Buonamico gravely. “Let me assure you of this one point: you are as close to a Francesco as I am ever going to meet in this modern era. Take it as a compliment my boy. The friars were all delighted with my choice.”

Seeing Buonamico painting again inspired Bávlos to work more on his carving of Notre Dame. By the week’s end, he had it finished: a tall, delicate Madonna sat with her baby on her knee. Her head inclined toward her son artfully, the shape having been dictated in part by the curve of the antler Bávlos had used. The young Iesh looked cheerfully out at the viewer while Notre Dame herself directed her gaze resolutely at her son. Bávlos was particularly pleased with the Virgin’s fingers: they were long and delicate, and they seemed bent in a natural fashion. He had also managed to handle the strange fabric images of southern art: Notre Dame’s clothing seemed suitably excessive: it looked like she had wrapped herself up in yards and yards of extra cloth, spilling over her shoulders onto her lap and wrapping around her back in long folds and creases. Antler was such a different material to carve in than wood: it held even the finest details and it made every bend and turn somehow softer and more graceful. Bávlos rubbed the finished carving with a combination of soot and gum that set out the sculpture’s etched details in sharp relief. Bávlos was able to make every aspect of the Virgin emerge: the crow’s feet around her eyes and dimples beside her smile, the ridge of her sleeve hem and the stitching of her shoe. When it was complete, he gave it to Buonamico. The painter was tearful again.

“The Madonna enthroned with Child,” he mused, “image of my guild. I shall cherish this statue, my friend.”

The very next day, Buonamico paid a visit to Bishop Luigi of Pisa, who was passing through Siena on his way to Rome. “Your excellency,” said Buonamico, bowing low to kiss the bishop’s ring.

“Buonamico, my friend,” said the bishop, smiling. “What a pleasure to see you again.” The bishop seemed to be waiting for something more, smiling solicitously. Buonamico cleared his throat.

“Again I have taken the gross liberty,” he said, “to procure for you an object which I believe you may deign not to despise.” He drew from beneath his tunic Bávlos’s carving with a flourish and deep bow and a certain tearfulness in his eyes.

“It is exquisite,” said the bishop, admiring the carving, tracing the smooth line of the Virgin’s shoulder with his finger. “French craftsmanship, I should say. Elephant ivory. Most rare.”

“I marvel at your excellency’s expertise,” said Buonamico. “So many clerics today are such dullards concerning the fine arts.”

“Indeed,” said the prelate with a smile, “Buffalmacco, I know what I like and, for the most part, I like what I have seen of your paintings. I am prepared to engage you for a major wall of the Camposanto. Please me there as you have done in Lucca and other walls will come your way as well.”

“Your excellency is most kind, most generous!” said Buonamico in his most ingratiating tone, “ Do you have a plan for the theme of the piece?”

“It shall be a fresco on a high theme,” said the bishop, tapping his chin. “The Slaughter of the Innocents, perhaps.”

“Oh yes, always a stirring theme for a fresco,” said Buonamico. To himself he wondered how welcome such an image would be in a church that was essentially a graveyard. As if reading the painter’s mind, the bishop paused and said, “Still, that theme may seem a little dismal for a funerary audience. What about the Beheading of John the Baptist? Or even better,” he said, tapping his nose, “The Stoning of St. Stephen?” That’s a favorite of mine.”

“Quite,” said Buonamico. The bishop’s tastes were consistent, if morbid. They gave Buonamico an idea.

“Your excellency,” he said, timidly, “What about a grand Last Judgment, done up with lots of vivid detail: jaws of death, damned being consumed, Christ in righteous judgment, and so on? That could fill a giant space, and it is certainly the final word in any artistic scheme.” Buonamico was going for broke, he knew. Last Judgments were climax pieces, final words in any church décor, and every painter who wanted undying fame simply had to do one. Getting a commission for a space large enough to do the topic justice, however, was a daunting task: it usually took a lifetime to land such an assignment, and then, often enough, the painter was too old to finish the work himself. Getting the Camposanto Last Judgment at his age would be a major feather in Buonamico’s cap.

“The Last Judgment,” said Luigi, petting the ivory, “Oh I do like the sound of that! Something really dramatic!”

“With perhaps images of your choice on the side of the saved—“ said Buonamico, temptingly. He knew that would be a prospect hard to pass up. The bishop could name his own friends and play God, guaranteeing them passage into heaven, at least in the fictive world of the fresco.

“Excellent suggestion!” cried the prelate. “So it shall be! When can you start?”

“I have the frescoes of San Francesco to finish here, your excellency, and then I am ready to go.”

“Wonderful,” said the bishop. “I will not be in Pisa for some time myself; the place is full of the Plague, you know.”

“I had heard that the city was suffering thus,” said Buonamico.

“Yes, quite,” said the bishop, “You were damned lucky to get out of the city when you did, Buonamico: a matter of days or weeks longer and you would have found yourself surrounded by pestilence! Most disagreeable, I can assure you!”

Buonamico remembered his time in Pisa and his friend’s insistence that they leave. As he watched the bishop cradling the Madonna which Bávlos had made, he felt a twinge of guilt at having used the sculpture to acquire a commission in the very place that Bávlos feared more than anywhere else. “Still,” he thought, “Bávlos is a good man. He gave me this sculpture to gladden me, and I have used it to increase my happiness even further. Surely he would not begrudge me the joy of a career-making commission like the Camposanto Last Judgment!” Nonetheless, Buonamico resolved not to mention how he had used the sculpture when he next met his friend.

“This Siena is clean of the Plague though, I am assured,” said the bishop.

“Oh yes, your excellency,” said Buonamico eagerly, “No sign of it here and no likelihood of it coming either, mark my words!”

“Good,” said the bishop. “That pestilence is as swift to take an artist or a bishop as a peasant, they tell me. I don’t intend to go anywhere near anywhere that has had anything to do with the Plague. They say you can catch it from the very sight of the sick!”

Buonamico crossed himself. The bishop noticed the gesture and did the same.

It was the first of May when they set off for Assisi: Bávlos, Giovanni, Nieiddash and Admirabilis. Giovanni thought it would take four days of walking to get there, but they brought enough food to make it in six so that the calf could gain his walking legs. When they started, however, they saw that their concern was unnecessary: Admirabilis was already a strong and tireless walker. Nieiddash seemed thrilled to be out in the air again, and her spirits filled the men with levity.

“Our Francesco liked to wander as well, I take it?” asked Bávlos.

“Oh yes,” said Giovanni enthusiastically, “he was an eager walker. In fact, it was his walking that brought him to his calling, they say.”

“How so?” asked Bávlos. He wanted to hear more of this intriguing and somehow reminiscent aspect of the holy saint.

“Well, he used to go tramping, our Francesco. He would walk about the countryside, thinking and praying, looking for where he could be of help.”

Bávlos certainly found this detail familiar: after all, he had walked across much of the world looking for the work that Iesh intended for him. “And did he find it?” he asked eagerly.

“Yes,” said Giovanni, “but in a strange way. A cross talked to him and told him what to do.”

“A cross?” said Bávlos, now surprised. This fellow was sounding more familiar all the time.

“Yes a cross. It was a painted crucifix in a ruined church on the outskirts of Assisi. Francesco came to pray there and the cross spoke to him directly.”

“Well what did it say?” said Bávlos almost in a whisper. His throat had gone dry.

“It said, “Come, repair my house.”

“So what did he do?” asked Bávlos, fascinated.

“Well you see, Francesco thought that the voice, that God, wanted him to repair the little church where he was praying. So he started at once to fix it up: repairing the walls and the roof and the door and such. Other men came to help him and that is how the order got its start.”

“So the order is really a group of church repairers,” said Bávlos nodding. This seemed to him a worthy thing. He hadn’t noticed any of the men showing much handiness in carpentry to date, but maybe they just were avoided such work during Lent.

“I am an inscribed member of the guild of masters of stone and wood, you know,” said Bávlos with some pride, “so maybe I can help as well.”

“Well, we don’t really do church repairs ourselves anymore,” said Giovanni, a little confused himself. “You see, after a while Francesco and his brothers figured out that God was talking about his entire church when he said ‘my house;’ the order has been trying to fix the entire church ever since.”

“Well, how on earth do you do that?” asked Bávlos, “and what is broken in this church you’re talking about? Is it in Roma?”

“The ‘entire church’ means all Christians—you, me, the people of Siena, the people of Firenze, the priests, the bishops, the pope…”

“My goodness,” said Bávlos. “And we’re all broken?”

“Well,” said Giovanni, “it is like this. At the time that Francesco lived, a hundred years ago, there was a lot of corruption in the church. The clergy lived pretty cushy lives and they didn’t seem too interested in serving the lay people, especially not the poor ones.”

Bávlos thought of his time with the cathedral canons in Paris and what he had seen over and over again in Pisa, Firenze, and Siena: the herds of well-off clerics massed in the front part of churches, saying their masses for each other and for daily payments while the ordinary folk watched from behind a screen, missing most of the events. “And they managed to fix this problem?” he asked dubiously.

“No, not really,” said Giovanni. “There is still a lot of the same going on, I guess. But we Franciscans try to give an example of another way to live. Francesco, he wanted nothing but what he could carry on his back, and his happiest times were spent out sleeping beneath the stars or in a little humble church.”

“Ah,” said Bávlos. So that was how the church could be repaired. He liked this Francesco more and more: he seemed to have thought with good logic. “That seems more possible,” he said. “So you strive to live a simple life?”

“We do indeed,” said Giovanni happily. “Why, just look at us today,” he said, shaking his shaggy head and raising his dark eyes to the skies, “We are walking beneath Brother Sun and enjoying the simple gifts that God has given us.”

“Brother Sun?” said Bávlos surprised, “Is that how you call the sun?”

“That’s how Francesco taught us to call him,” said Giovanni reverently. Bávlos was amazed. This Francesco seemed to have had understanding far beyond the ordinary Italian. Sámi people knew the sun as Father, but calling him brother was close, at least it was a sign of kinship. “How did he teach you this learning?” he asked.

“He sang it,” said Giovanni.

“He sang it?” said Bávlos surprised. Could it have been that Francesco knew joik as well?

“Listen,” said Giovanni. He threw back his head and began to sing a joik for the sun:

Be praised my Lord in all you’ve done

Especially in our brother Sun.

He brings us light when it is day,

Fair, shining, splendid, every ray,

With you in likeness one.”

“Francesco sang that?” said Bávlos. It seemed to him that he knew now why the cross had told him to learn about Francesco.“Did he sing of other such things?”

“Oh yes,” said Giovanni, “he sang of Sister Moon and stars, of air, wind, and tempests…”

Bávlos was so interested in this revelation that his mind began to wander. He thought of Biegga-olmmái, Wind man, the one who brought both good and ill winds and weather. How was it that Francesco had known about “Brother Wind?” How was it that he knew how to joik, or that he valued a Sámi way of living? It was if this man a hundred years earlier had been trying to do exactly what Bávlos found himself doing every day now: trying to convince his friends of the real meaning of being Christian, of the ways that Iesh valued and desired to see lived out in this prosperous but easily deluded land. “This Francesco,” he said at last, “He was from Umbria?”

“Yes, certainly,” said Giovanni; “at least his father was, anyway. His mother came from France they say.”

“From France,”said Bávlos, nearly shivering.

“Yes,” said Giovanni. “Francesco’s father had a lot of dealings up north and he brought her home to Assisi after one of those trips. That’s why he named his son Francesco: he wanted to honor his wife.”

“What was she called?” asked Bávlos.

“I don’t know,” said Giovanni, shrugging his shoulders. “No doubt someone will know in Assisi. There are brothers there that can tell you something about every day of Francesco’s life.”

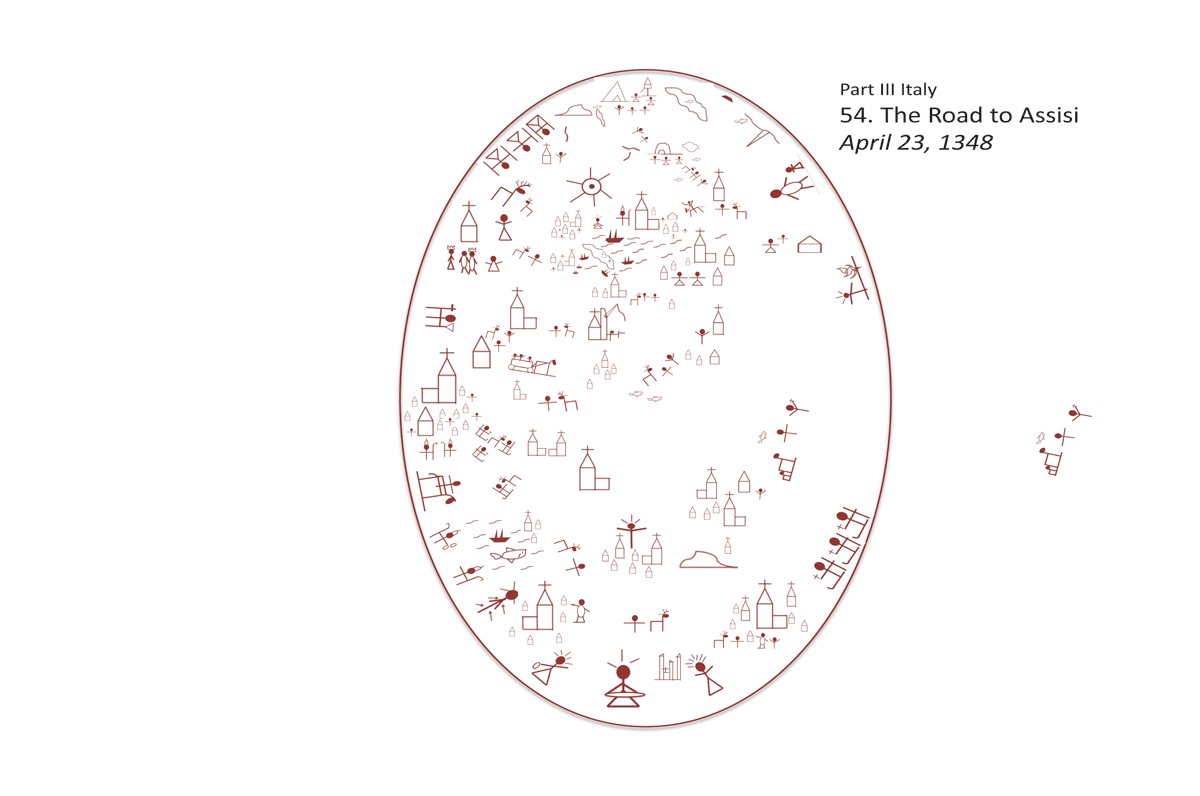

It was midday now, and the friends stopped to eat. Bávlos took the pack off Nieiddash’s back and let her loose to graze and relax. Admirabilis took advantage of the moment to suckle and then to bound around the meadow where they had stopped. Giovanni and Bávlos sat down to eat their bread and cheese and then Bávlos pulled out his drum to add more drawings to its surface.

“What is that?” asked Giovanni with interest.

“It’s a kind of map,” said Bávlos. “It reminds me of where I’ve been and what sorts of things I met with there.”

“Ah,” said Giovanni, gazing wide-eyed. “You have been to many places.”

“Indeed I have,” said Bávlos, “although sometimes the details are fading from even my own memory. Giovanni, do you happen to know how to write?”

“I do!” said Giovanni enthusiastically. “I learned only last year and I am really rather good at it, they tell me. Of course, I don’t know Latin too well yet, but I can certainly write in Italian.”

“Then I could tell you what these different figures are on my drum and you could write that on my drum?”

“I think I could,” said Giovanni; “at least I could try.”

“Excellent!” said Bávlos with delight. “Let us begin at once!” Bávlos began to describe the different figures he had drawn, starting with the lands of Father and the lake of Mother and working all the way down to Siena, a place he had only just added to the drumhead. Giovanni listened in awe at the many stories Bávlos had to tell and then dutifully scribbled some words on the drumheads near each figure. It took several hours for the friends to finish the task but they both enjoyed the work thoroughly.

“You know,” said Bávlos, when the friends had gotten to the figure of Turku, “that stream down there looks like it might be perfect for fishing.”

By the end of the day the friends had finished writing things on Bávlos’s drum and caught three fish. Bávlos milked Nieiddash for a little milk for them to drink as well. They started a fire, and Giovanni happily sang the saint’s joik for the fire:

Be praised my Lord in Brother Fire,

Through whom you lighten darkest night.

His power and strength we so admire,

He is a fair and cheerful sight.

It seemed to Bávlos that he could hear the happy crackle of the fire in Giovanni’s singing and the wisdom of Francesco in the words.

“You know, Giovanni,” said Bávlos as he cleaned the fish, “in my life I have never eaten fish without first giving thanks for it. Do you suppose it’s okay to do so now?”

“Of course!” said Giovanni, “How could that not be right?”

“You say it in Italian,” said Bávlos, “and I’ll say it in my language.”

As they prayed, Bávlos carefully dispensed some offal onto the ground by the river. “A share for Iesh,” he said.

Giovanni nodded reverently, “Good idea,” he said.