Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348

a free multimedia novel by

Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison

|

Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348 a free multimedia novel by Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison |

|

|

|

|  |

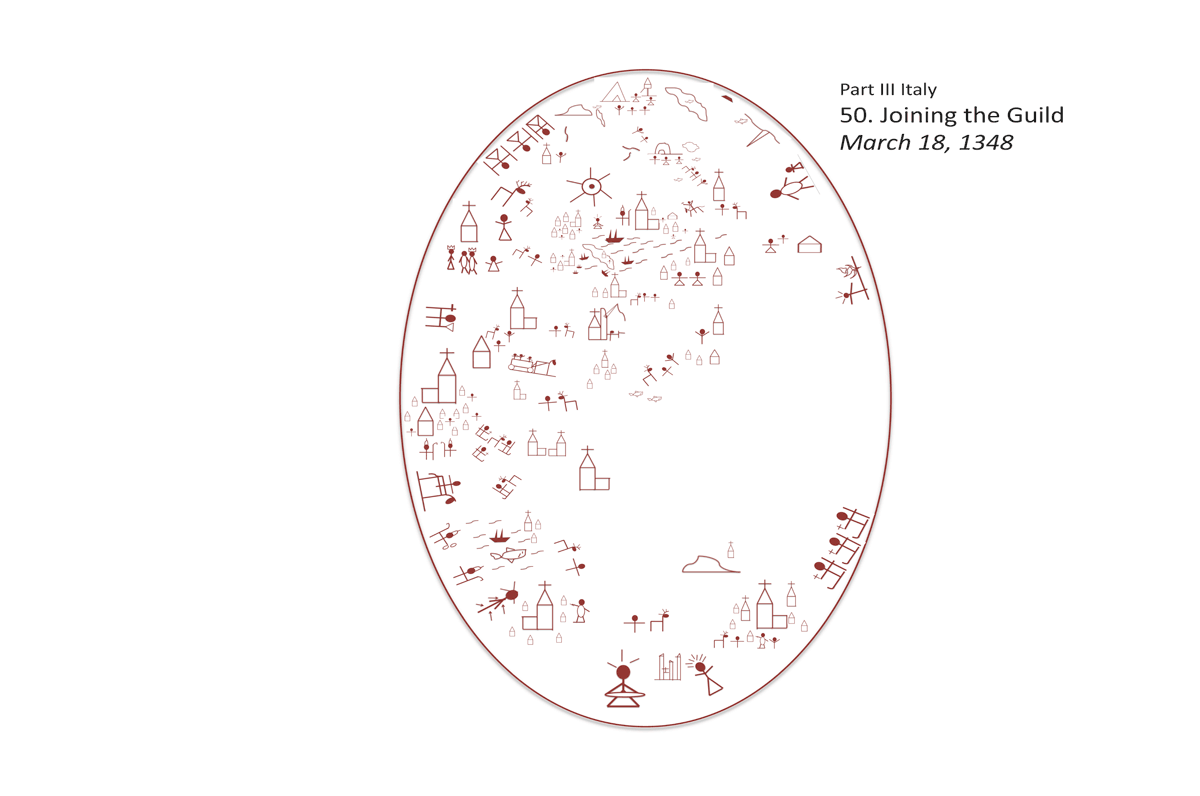

50. Joining the Guild (March 20, 1348)

For the cult idols of the nations are nothing, wood cut from the forest, wrought by craftsmen with the adze, adorned with silver and gold.

Bávlos spent another couple of days in the forest, finishing his sculpture for the waterfall and trapping some more meat for himself and Brother Bartolomeo. He skinned the deer and boar to save the pelts for making new shoes and other needed items. It felt good to be living off the land again, and Nieiddash was thriving in the rich forest of this gentle clime. Eventually, though, he remembered that Iesh had called him to this land to help Buonamico, so he returned to Firenze with Nieiddash and took up his old post as the painter’s apprentice. In his spare time, he sat and carved statues. The themes that Buonamico took up in his art became the subjects of Bávlos’s carvings as well, although always with a different style and feel to them. Bávlos was beginning to amass a sizeable collection of statues, which he tended to give to people he met through his work with Buonamico or at local churches.

“Friend Paolo,” said Buonamico one day after Bávlos’s return, “I have something of importance to discuss with you.”

“Yes?” said Bávlos. He had never heard such a serious tone in his friend’s voice before, except as a prelude to a joke.“When you came to me, lad,” said the painter, as if many years had since transpired rather than a matter of weeks, “I agreed to take you on as an apprentice. And you have served me well.”

“Yes?” said Bávlos again, still waiting for his friend to get to the point. “Am I no longer doing so?”

“You are, lad, you are!” cried Buonamico, slapping him on the back. “It’s only, well, you seem to be a fine carver in your own right.”

“Thank you,” said Bávlos. “I do love to carve.”

“Well, that’s just the point,” said Buonamico shaking his head and gesturing widely, “You cannot just go about doing anything you like! Carving, for instance: if you want to do that you must join the arte!”

“The arte?” said Bávlos, repeating the term. Was this not this simply the term for art, for making beautiful things?

“The arte!” exclaimed Buonamico again. “Surely in your land they have such institutions?”

“I don’t know what sort of thing you mean,” said Bávlos truthfully. Understanding words was one thing, but he suspected that this was an unfamiliar concept as well.

“Come with me,” said Buonamico with sudden vigor, “I will take you to a place where you will understand.” Buonamico led his friend out into the wide and bustling world of Firenze. Everywhere he looked people were out and about, talking, laughing, carrying objects, conferring gravely. There were high figures in lavish clothes, clerics in religious garb, merchants, farmers, and peasants. Each was dressed in distinctive clothes from head to foot, announcing their identities to the world in unambiguous terms.

“Look around you,” said Buonamico, “Do you see how everyone is dressed differently? That’s because they have different ways of living. And if they are artisans, like you or I, they belong to a particular guild, an arte.”

“Ah,” said Bávlos, “just as you are in the Arte dei Medici e Speziali.”

“That’s right, my boy,” a guild of the highest quality.”

“Well, am I in that guild too?” asked Bávlos innocently.

“Of course not!” cried Buonamico incredulously. “Do you remember joining it?”

“No,” said Bávlos.

“Anyway, my guild is for doctors, scent makers, pharmacists, pigment makers and painters—not for sculptors. Sculpture does not belong among the high arts but among the minor.”

“What are you talking about?” said Bávlos with some exasperation. “None of this makes any sense to me.”

“Let’s begin again,” said Buonamico patiently. “Here we are.” They had come to an imposing building on the Via dei Cavalieri, with great archways on its first floor and ample loggias. On its second floor it had an elaborate shield depicting the Virgin enthroned with the baby Jesus on her knee. “This, lad, “ said Buonamico proudly, “is the seat of my guild.”

“I see,” said Bávlos. “You go here to sit?”

“We come here to meet, boy, to meet. It is here where all the men worthy enough to work as medici or scent makers or painters come to manage our business.”

“Manage your business?”

“Yes,” said Buonamico. “You see, we have to have some standards, for the good of the public. When a person comes into the shop of a medicus or asks for a painting to be done, that person deserves to expect a certain level of quality, a certain reliability, for an expectable price. If just anyone under the sun took up doctoring—if say, someone like you came along with outlandish ideas—”

“My ideas of healing aren’t outlandish,” said Bávlos, irritably, “although they do come from abroad—”

“Well, that’s simply my point, my boy,” said the painter, trying to avoid what he knew was a sore point for his friend, “they’re not the usual, not the expectable, the proven methods of our art.”

“So anyway,” said Bávlos, seeking to move the discussion forward, “So this guild somehow prevents anyone from being a medicus unless they do things like everyone else.”

“That’s right,” said Buonamico. “Membership is limited to those who are the legitimate sons of local medici, or, if they come to the profession from outside of a family line they must pay a fee of six fiorini, double that if they are not from Firenze.”

“So I would need to pay twelve fiorini to work as a painter here.”

“That’s right, lad, now you’ve got it.”

“And what do you use this money you collect for?” asked Bávlos.

“Well, to run the guild,” said Buonamico. “You see, we have all sorts of expenses and duties and offices to fill in the guild.”

“Oh you do? asked Bávlos, “like what?”

“Well, we have a leadership of six consuls, for instance,” said Buonamico, tallying up offices on his fingers, “plus one chamberlain, one notary, twelve council members, eighteen goodmen, six statutories, and three officers; the consuls are elected twice a year and serve for six months each. They meet weekly, while—”

“What does it mean to ‘elect’” asked Bávlos.

“’Elect’? That just means to choose, lad. We decide who among us will be our leader for the next half year by writing their names on a ballot. The men with the most votes get to serve.”

“Ah,” said Bávlos. He recalled this custom from Pekka and his brothers. He liked the sound of this idea. It was different from the inherited privilege that seemed to govern all things in all these lands of the south, from princes, to bishops, to farmers. “And anyone can get elected then?” said Bávlos.

“Well, anyone within reason,” said Buonamico. “You have to be a man of substance, with a lot of respect of others before you’ll get enough votes.”

“I see,” said Bávlos. “And these people meet about things weekly? What sorts of things?”

“Well, prices and standards and things,” said Buonamico. “The chief thing really is that we don’t want too many medici or painters in the city: too many and no one can make a living at it!”

“I see,” said Bávlos. “Are there other such guilds?”

“Why of course there are!” laughed Buonamico. “That’s what I have been trying to tell you: there are a slew of both Major and Minor arts in the city today.”

“Such as?” asked Bávlos.

“Well, such as, on the Major side, there are the Jurists and Notaries, the Merchants, the Wool Traders and Workers, the Silk and Fabric Dealers, and the Furriers. It was one of those guildsmen that bought your pelts, remember? Giacomo the Furrier over on the Street of the Furriers.”

“Ah,” said Bávlos, “Yes I remember. So people’s names tell what guild they belong to?”

“Well, sometimes,” said Buonamico. “But you can never be sure. Take old Averardo de’ Medici for instance.”

“Averardo de’ Medici—he’s a medicus like Master Simone?”

“No he isn’t,” said Buonamico. “Too poor for that. I think his grandfather used to be one, before he moved here from Mugello. But there are a lot of fine medici in this city, lad, as you know, and these village healers had no chance of making a living as a member of my fine guild.”

“So what does he do for a living then?”

“Well, his father joined the guild of the Money changers, and he was in it too until he died a couple years back.”

“Money changers? What do they do?”

“Why they handle money!” said Buonamico. “That should be obvious.”

“You need someone special to do that?”

“Of course! These money changers keep all the supply of gold and silver in the city. So let’s say I need some gold foil for a painting I’m doing—“

“Gold foil?”

“Yes, thin sheets of gold. Let’s say I’m making an Adoration of the Magi and the church says ‘Go for the works!’ Then that means I need to do some gilding. So when I get the painting done, I have to apply gold, real gold, to the three kings’ crowns and to wherever else it seems warranted—angels’ wings, heavenly trumpets, rays coming from the great star, you name it—so that the painting really overwhelms the viewer.”

“Yes, I can imagine!” said Bávlos. Truthfully, paintings like these were not his favorite, but he had noticed that the biggest and grandest cathedrals did have such works in prominent places.“So you get the gold from a money changer.”

“Yes, exactly,” said Buonamico.

“But how does a moneychanger make a living off that?”

“Well, of course, the moneychanger got the gold from someone else and paid one price, then they sell it to you for a little more and that gives them a profit.”

“Ah,” said Bávlos. He recalled how his pelts had brought more money here in Firenze than in Sweden. If he had been a merchant he might make money just transporting pelts to Italy and reselling them, without even having trapped or skinned any of the animals himself.

“And that’s not all,” said Buonamico, wagging his finger. “Say the painter doesn’t have the money to buy that gold foil until the painting is complete and he receives his payment from the patron.”

“Yes?” said Bávlos.“Well, I need to get the painting done before I get paid, and I need the gold to get the painting done. So what do I do?”

“Well, I don’t know,” said Bávlos. “Could you just get the moneychanger to give you some gold and promise to pay him back later?”

“Precisely!” said Buonamico with a smile. “And that’s what the moneychangers do: they will give you the gold worth, say one hundred fiorini today—that’s those coins we use—and say, a month later, when the painting is done and you’ve got the payment in your pocket, you pay them back the one hundred plus a little more, maybe ten or twenty fiorini.”

“Why do you pay them back more than they lent you?” asked Bávlos.

“Why, to say thank you, of course!” said Buonamico. “I mean, they’ve done you a favor!”

“I see,” said Bávlos hesitantly. “Still, it doesn’t seem such a big favor if they are going to become richer for doing it.”

“Whatever do you mean?” said Buonamico frowning.

“I mean, in my land, we do it differently. When someone is in need of something you lend it to them. And when they can pay you back, they do. But if they don’t pay you back, well, you go over and talk it out with them.”

“Talk it out with them?”

“Sure, I mean, if you don’t pay me and you have a good reason for it—like a really bad run of luck or a family member dying or something—then I say, ‘Okay, you can pay me back in some other way down the line. I lent you some reindeer meat and you can pay me back in fish next time you get a good catch.’ But if you’ve got plenty of the thing you borrowed from me on hand and you just refuse to pay me back out of spite, well then, I’m never going to let my daughter marry your son. And I won’t want to hunt with you anymore.”

“Oh ho,” said Buonamico, rolling his eyes. “Look around you boy. This city has scores of people, thousands of people, in fact more than one hundred thousand people! How many daughters are you planning to have? In the modern world, a money changer has got to charge a little for the loan so that he can make a living and so that he won’t get in trouble if you fail to pay him back!”

“I see,” said Bávlos. Things were certainly complicated in this world.

“Anyway,” said Buonamico, “It’s not like it’s a lot of money. They lend you a hundred and you pay back a hundred and ten, or maybe a hundred and twenty. Not a big concern to a person with a noble heart. And these types don’t make much off it all. Look at poor Averardo’s place,” he said, gesturing at a narrow house near the church of San Tomasso. A thin, haggard woman stood at its doorstep, sweeping vigorously, while two small boys played around her feet. “Not much of a living he made, eh? I wish to God that those ragamuffin boys of his get a little more smarts than their poor dimwit father had. I mean, just having him around with the name Medici besmirches our fine guild.”

“I suppose,” said Bávlos. He looked at the boys as they darted in and out of the little house’s doorway. They had a hungry look to them and their clothes were worn and tattered.

“No, money changers aren’t like artists, my lad,” said Buonamico sighing in a self satisfied way. “They’ve managed to get their guild into the Major Arts category, but they don’t have the prestige of a pharmacist or furrier.”

“Well,” said Bávlos, “But none of these guilds seem to have anything to do with carving.”

“They don’t lad, they don’t. That activity belongs to the lower order of guilds.”

“I see,” said Bávlos, rolling his eyes. “And what are these ‘lower’ guilds?”

“Well, let’s see,” said Buonamico. “There’s the Guild of the Butchers, Fishmongers and Innkeepers, that’s a prosperous one, then there’s the Bakers, a little less well-to-do, and the Dealers in Olives: lots of different food-related guilds, you see. Then we have the Cobblers’ Guild, they’re numerous enough, and the Ironsmiths, the Dealers in Linen and Junk—”

“Junk?” said Bávlos. “Yes, used things, things that are put up for sale again. The Junk Sellers have the right to sell such wares.”

“I see,” said Bávlos. “What other guilds are there?”

“Yes, yes, boy, don’t interrupt now. There’s the Vintners, of course, a very worthy guild, eh?” Bávlos nodded and smiled at his friend’s wagging head and wink.“And the Hostellers, and the Tanners and Leatherworkers, the Makers of Swords and Sheaths, the Woodcutters, what am I leaving out?”

“Is there a guild for carvers?” asked Bávlos impatiently.

“Yes, yes, lad, that’s the one. The very worthy Masters of Stone and Wood. Not a bad guild at all, I must say. Why their members build all the buildings in town, including the cathedral and churches! And all the sculptors belong to the guild too. Of course, they’re not under the patronage of the Virgin and Child, like my guild—”

“Patronage?”

“Yes, you know, special protection,” said Buonamico. “The protectors of your guild are four Roman sculptors: Saints Sinforiano, Claudio, Nicostrato and Castorio.”

“What did they do?” asked Bávlos.“It’s what they didn’t do,” said Buonamico, “that got them in trouble! The emperor Diocletio—a pagan that one—he wanted them to make a statue for him of the god Esculapio, a god of healing.”

“Aha,” said Bávlos, “so they didn’t like you medici either?”

“Well, they didn’t want to make a statue of a pagan god, you see, lad. So they refused, and the emperor, not taking kindly to such a refusal, tortured them to death. They’re a hard subject to paint, I must say: four men of about the same age, nothing really particular about them except that you can put hammers or chisels in their hands…Ah,” said Buonamico at last, “We’ve come to the seat of the guild.” The men were standing before a stocky building of rough stone not far from the main civic square of the city. Above its main door they saw a shield emblazoned with the figure of an axe.

“We’ll go in here, lad, and get you properly enrolled. Then you can carve to your heart’s content, though not more than the specified hours: twelve hours per day in the summer, a mere eight in the winter.”

“All right,” said Bávlos. “Let’s do so. Still, I can’t help finding this all strange.”

“What’s strange, lad?”

“Well at home we do all these things ourselves. Look at my clothes: all made by my mother and sister. My shoes, made by them as well. My bow, made by my father. My arrow tips, made by my brothers and me, my carvings, made by me in my time by the fire—”

“Yes, yes, it’s a hard life you’ve got back there,” said Buonamico smiling. “But you’ve been fortunate enough to make it to civilization now and can reap the benefits of an easy life.”

“Easy, I suppose,” said Bávlos, “but our life—”

“Yes, yes,” said Buonamico, raising his hand and turning his head away, “Your life is beautiful and free in its crude simplicity. I know lad, and sometimes I almost agree with you. But this is Firenze, the center of the world, and you’ve got to fit in.”