Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348

a free multimedia novel by

Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison

|

Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348 a free multimedia novel by Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison |

|

|

|

|  |

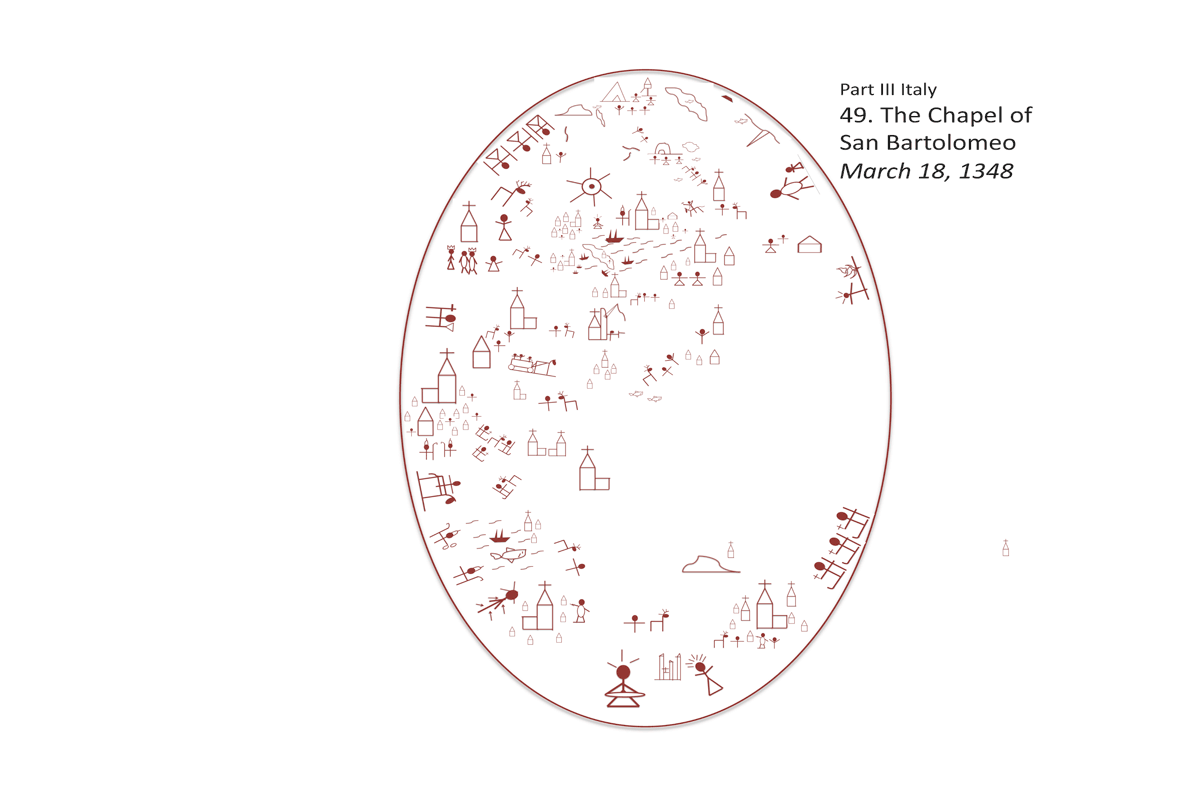

49. The Chapel of San Bartolomeo (March 18, 1348)

The.Blessed are you, O Lord, the God of our fathers, praiseworthy and exalted above all forever.

“How on earth did you kill that boar by yourself?” cried Buonamico in admiration, rising from his seat to admire the beast and slap his friend on the back. “Boar hunting is a dangerous sport even for a group of skilled men on horseback with a pack of hounds in tow!”

“I made a pit trap like we use back home to catch wolves,” said Bávlos with a satisfied grin, “and this fellow tumbled in. I was able to get a couple of arrows into him to kill him.” Bávlos was proud of his skill. Traps like his didn’t usually prove so effective so quickly. Iesh was clearly intent on helping him show his friend the excellence of Sámi ways.

“Hardly sporting, man,” said Buonamico a little disappointed. “I mean, you couldn’t call that a truly ‘noble’ hunt.”

“I guess not,” said Bávlos. “Where I’m from, hunting is purely for food, and we don’t take risks we don’t need to. Trapping is the way we catch most of our meat.”

“But the poor beast,” said Buonamico. “He hardly had a chance!”

“So now you do feel for the animals!” said Bávlos with a laugh.

“Feel for them, yes, on occasion,” said Buonamico thoughtfully. “But I don’t talk to them, of course, and I certainly don’t think they have any notion of the Lord or salvation! I wouldn’t thank them for being my dinner, if that’s your meaning, any more than I’d thank an olive for being willing to sit in brine.”

“There’s how we’re different, I guess,” said Bávlos. “I don’t mind taking the boar’s life by a trick, provided I apologize to him for it and thank him properly for his gift. He and I are both creatures of the Lord, but one creature sometimes has to eat another if it is to stay alive.”

The monk was watching the conversation intently, nodding on occasion. But he did not offer any opinions on the argument. Instead, he gazed out over the vast valley, beyond which the sun was setting in a gloriously reddened sky.

Bávlos soon learned that Brother Bartolomeo and Buonamico knew each other from some years ago. The monk had been a member of the Servites at the church of the Most Holy Annunciation in Firenze and had worked as a painter in his own right. He had left the monastery with his abbot’s permission to tend this little church on the mountain, a task he had performed now for the past seven years.

“How did you come to leave Firenze to tend this church?” asked Bávlos.

“It was the miracle that did it,” said the monk.

“Miracle?” asked Bávlos with interest.

“Ah, forgive him, friend Brother Bartolomeo,” said Buonamico. “My companion is a pilgrim from the far, far north, and he knows little of Firenze, even of its greatest events.”

“I am not upset at his not knowing,” said the monk simply. “In fact, in some ways it is a relief. The days after the miracle were arduous for me: people always asking questions, the examiners from my order and from the bishop, pilgrims from afar, some of them royal. I felt after it all that God wanted me to withdraw, to let the blessed image speak for herself and to thank the Lord for the miracle through simple service to pilgrims on this road. That is how I came to this chapel, conveniently named for my patron saint.”

“Tell me of this miracle,” said Bávlos eagerly.

“I will,” said the monk, rolling up his sleeves. “I am a native of Firenze, born and bred, like Buonamico your friend. I grew up in the neighborhood where the Church of the Most Sacred Annunciation stands, and when I turned fourteen, I entered the monastery there as a novice. That was more than forty years ago. The order itself had its founding nearly a hundred years back, when seven holy men banded together in the service of the Virgin. This is why we are called the Order of the Servants of Mary, and the Virgin has blessed the order with her protection and guidance from the very start.

“Now the church of my order is a fine one, and has its share of chapels and altars, as all good churches do. When I first entered the order, I often was assigned as an assistant at the chapel of the Annunciation, where I aided the priest in saying the mass and leading the faithful in devotions to our Lady. In time I became a priest myself, and continued to serve at that altar. That’s why they approached me about the art.”

“The art?” asked Bávlos.

“Yes,” the monk continued. “The order determined that the chapel deserved greater ornamentation. A full painted triptych was in order, and what other theme should it take but that of the Annunciation? I had been learning painting for some years, not in the way of a great professional such as Buonamico here, but on my own, and with some small measure of success. Nonetheless, the task of painting that sacred event filled me with a profound dread. How could I do justice to such a theme? How could one of such limited talent undertake such a task, and in a city of breathtaking masterpieces of art? I set out to view as many versions of the Annunciation as I could, visiting churches throughout the region. I took notes on what seemed to work or not about the paintings I’d seen. I talked to artists and priests, even bishops. And I drew sketch after sketch of the picture I envisioned. At last it started to take shape, except for one thing.”

“One thing?” asked Bávlos, fascinated.

“Yes,” said the monk. “I could not imagine the Virgin’s face. I knew it was the most important part of the entire painting, but I had no clue of what it should look like or where I should turn for a model. Should I ask one of my sisters to model? Should I simply copy the image of some old master? Nothing seemed to work and I became deeply depressed.”

“Not a problem I’ve ever had,” said Buonamico, musing. “I mean, the world is full of lovely faces.” Bávlos recalled the sketches he had seen bearing his own likeness in Buonamico’s workshop.

“Ah, that is because you have talent,” sighed the monk nodding, “I had none. At last I decided that I had to make a start on the painting anyway. The face would have to wait until later. In the meantime, I could paint the angel and the Virgin’s body, and the room and its details. I set to work. The result was not that bad.”

“But the face?” asked Bávlos. “What did you do about the face?”

“I left it blank,” said the monk, shrugging his shoulders. “It was beyond me. But then the miracle happened. I prayed to the Lord for his guidance and found myself overwhelmed with exhaustion. I lay down right there in the church by the chapel and fell asleep. And in my dream, I saw an angel come, take up my brush and paint, and set to work on the face. When I awoke, the face had been completed. Completed by an angel. I had seen the whole thing occur in my sleep and now the painting was finished. I ran to the abbot to tell him what had happened.”

“What did the abbot say?” asked Bávlos, now very excited.

“The abbot just laughed at first,” said the monk, shaking his head. ‘You are too modest, ‘ he said, agreeing to come to the chapel, ‘let me see your work.’ But when the abbot came, he saw—”

“He saw the face,” said Buonamico, finishing his friend’s tale, “and crossed himself twice, falling down to kneel. It was obvious, you see, that the face on that Virgin was not painted by human hand. Let me tell you, lad, I have been to that chapel a thousand times in the last seven years, as has nearly every artist worth his salt in all of Italy. And everyone agrees: it is a face that is beyond all human abilities to produce.”

“It is indeed,” said Brother Bartolomeo, simply. “The rest of the painting is, well it’s workmanlike at best. But the Virgin’s face, her face—” his voice trailed off into a raptured sigh. Then he seemed to recover to complete his tale.

“Well, people started to hear about the painting and they started coming to see it. From all over Firenze they came, and then from the villages nearby, and then from even rival cities: from Pisa, and Lucca, and Siena. They came streaming to the church to see the face painted by the angel, and they began to experience miracles. People were healed of their maladies at its sight. Pains disappeared. Sick infants revived. Brides began to come to the chapel to pray before their weddings and women who were expecting came to pray for their babies. The stream of pilgrims has not stopped one bit since the day the angel completed that painting and I don’t think it ever will. It is a miracle that anyone can go and see any time they like.”

“My,” said Bávlos. “And you, how did that make you come here?”

“Well think of it, man!” said the monk with a grand gesture. “Everyone wanted to talk to me! Everyone wanted to see if the angel would help me again. I had more requests for paintings than I could do in a lifetime, and more expectations than I could ever live up to. It was a nightmare; not that I wasn’t grateful, mind you, but a nightmare just the same!”

“So you decided to come up here,” said Bávlos.

“I prayed and I fell asleep. In my sleep I saw this hillside and this little church, standing derelict. And my patron saint, Bartolomeo, came to me and told me that I could tend his church. So the very next morning I went to see the abbot and told him of my dream.”

“And he sent you here?” asked Bávlos.

“One of the brothers was from a farm up this way. When he heard of my dream he remembered this little church and wondered if that is the one I had dreamed about. When I saw it, I knew it was the one.”

“And you’ve lived here ever since?”

“Yes, indeed, and very glad of it too. My brothers from the order come to visit regularly and bring me food and news. But pretty much I live on my own out here and am happy.”

“I can see why,” said Bávlos.

Buonamico grunted.”You turned your nose up at a grand career,” said he. “I mean, sure your work was inferior to the angel’s, but you could have produced some lovely paintings nonetheless and those would have led people to God. As it is, why, just look at your chapel: not an inch of decoration except for that sky motif around the altar, and that done pretty crudely too, I might add.”

“I did that sky,” said the monk smiling.

“Well, yes, er,” said Buonamico embarrassed, “well, perhaps it was good that you gave up the painting, but—”

“But couldn’t I decorate the chapel a little more?”

“Yes,” said Buonamico, his voice rising, “I mean, it’s an insult to San Bartolomeo that you haven’t even bothered to give him a fresco!”

“I know,” said the monk mournfully, “But I can’t. I can’t bring myself to paint after the miracle: nothing can ever be the same. It would seem an act of disrespect for the angel’s help if I ever painted again. Or that I was expecting the angel to come to me again in my life. Such is too much to ask.”

“Well then,” said Bávlos, “in that case, I can make you a sculpture of Notre Dame and child for your chapel, and Buonamico can make you a San Bartolomeo!”

“Wait a minute!” said Buonamico quickly, “Let’s not get hasty! I mean, I don’t have any of my equipment here at all!”

“I have mine,” said the monk enthusiastically, “You could use my paints and brushes. I have everything! Would you do that for me? Buonamico, old friend, would you paint me a San Bartolomeo?”

“Hmn,” said the painter thoughtfully. “Tell you what. You give me a decent bed to sleep on and a roof over my head while I’m working, and for as long as Paolo’s wild boar lasts, I’ll work on decorating your chapel walls.”

“That’s a deal!” cried the monk and Bávlos together.

The next week passed pleasantly for the three men. Bávlos busily carved two statues, one for the church: tall and hefty, from a large piece of wood that one of the neighboring farms had stored in a barn, the other shorter and more slender from a piece of weathered wood he found in the forest. Both sculptures evinced their maker’s characteristic style: the Virgin was tall and shapely, with a natural curve to her body and a contended, cheerful smile. She sat with her son on her knee, looking outward at the viewer with a combination of majesty and friendliness. Brother Bartolomeo was amazed by the speed and seemingly effortless skill by which Bávlos approached his work: it was if the sculpture simply emerged from the wood of its own volition. In the mornings and afternoons, Bávlos would go off to tend his snares and check on Nieiddash. She was finding lots to eat in the forest nearby and putting on weight quickly.

Buonamico, for his part progressed more slowly at his task. The wall had to be prepared for paintings first and it was tiring and difficult work. The stones had to be smoothed of any large protuberances and gaps and chinks filled in. Then a layer of rough plaster had to be applied and allowed to cure. Bávlos and Bartolomeo both helped with this effort. When it was finally time for the frescos, Buonamico would lay a layer of fresh fine plaster to the surface—a giornata—and then begin to impregnate it with the pigments which would dry to the colors desired. One should only apply plaster to the area that one could paint in a day (hence the term giornata, or “day’s worth”), since the crucial chemical process involved in the technique had to take place while the plaster was wet. Other details could be added later, on top of the dry plaster, but the heart of the fresco emerged on the wet. Buonamico began to design a cartoon for the figure of San Bartolomeo that he planned to execute to the right of the altar. On top of his work, though, Buonamico also had his other characteristic habits: his mealtimes were long, and conversation was a constant part of his waking life. Bávlos began to understand how strange it must be for Buonamico to imagine being quiet as a positive thing.

One evening, when he and Buonamico were sitting on the bench of stone to one side of the church’s front door and looking out over the valley, Bávlos tried to discuss his views of the wilds with his friend. Maybe now he would understand.“Out here I feel free,” said Balvos simply.

“Free? Free lad?” said Buonamico incredulously, “Free from what? Free from being devoured by beasts? Free from the cold? Free from starvation? Free? I think not!” Buonamico’s opinion clearly had not changed.

“Free to be, I mean, simply to be,” said Bávlos again. Why was this concept so difficult to convey?

“The freedom you speak of lad is the freedom of clerics, not painters,” said Buonamico, nodding his head and looking over his shoulder to indicate Brother Bartolomeo. “ I have not been called to that kind of life, washing in ice water, wearing a hair shirt, sleeping on stones!”

“You were called to be a Christian, though,” said Bávlos, pursuing the point.

“I’d hardly call it being ‘called,’ lad. I was lucky enough to be born to Christian parents in a Christian land and that took care of it all.”

“It is true,” said Brother Bartolomeo, who had come to join the friends. “He was not called to Christianity in the same way as you were Paolo. Nor was I for that matter. For us it is harder to see what we already have than for you to see what you have lately been given.”

“I think I understand,” said Bávlos thoughtfully.

Buonamico took up the topic. “It’s like this,” he said: “We bring you God and now you have an inkling of what we simply take for granted here in our own land. For you God is difficult to understand because, after all, he is not from your land, is he?”

Bávlos cleared his throat. “God made all people, I have learned,” said Bávlos, “So I am reasonably certain he made the Fenni too.”

“Perhaps,” said Buonamico, “but he made us to teach you how to live right.”

Bávlos bit his tongue and said no more. There was no way to explain to Buonamico that Iesh had called him to Italy to teach people here how to live a better life, to explain that Iesh had sent him to Buonamico in particular. Bávlos could not see how to explain such a thing to one whose heart was so closed to all such views, so secure in the superiority of his own land’s ways. Despondent and tired, Bávlos went off by himself that evening, to pray and to think. The image of Brother Bartolomeo rose in his mind and he imagined the desperation that the monk had felt about his inability to paint the Virgin’s face. Like Bartolomeo before him, he decided to pray for guidance and go to sleep.

The next day at Lauds, Bávlos found his answer. Brother Bartolomeo quietly chanted the canticle while Bávlos and Buonamico knelt by.“Benedicite omnia opera Domini Domino,” he sang: “Let all the Lord’s creations bless the Lord!” Bávlos listened carefully.“Sun and moon, bless the Lord, praise and exalt him above all forever. Stars of heaven, bless the Lord,praise and exalt him above all forever…”

“Do you hear what he is singing?” whispered Bávlos.“Certainly,” said Buonamico irritably, “I should think I can understand Latin better than you!” On and on the monk chanted:“Dew and rain, bless the Lord;praise and exalt him above all forever…”

Bávlos was happy now. This was a Sámi prayer, given up in a Sámi way.

“You dolphins and all water creatures, bless the Lord, praise and exalt him above all forever.” Bávlos thought of the dolphin that had helped him to land.

“All you birds of the air, bless the Lord; praise and exalt him above all forever." Bávlos thought of all the birds he had trapped and how kind they had been to give their lives for him.

“All you beasts, wild and tame, bless the Lord; praise and exalt him above all forever….” Bávlos beamed as he looked at his friend. Iesh was speaking, and Buonamico had to hear him, like it or not.

“You see?” said Bávlos after the prayers were over, “My ways and those of God are not so different after all.”

“Hmph,” said Buonamico. “I have a fresco to do.” He began to apply the fresh plaster to his wall. There would be no more discussion today. That evening, over dinner, when evening prayers were ended, Buonamico announced that he would be leaving the next morning.

“Tonight, I think, we are dining on the last of Bávlos’s boar,” he said impressively. “Tomorrow I will be returning to Firenze. I have business to attend to. This has been a wonderful visit, friend Bartolomeo, I thank you for your hospitality. And friend Bávlos, I have enjoyed our time together greatly, even the rough living in the forest. But I need to get back to the workshop and to my commissions. I have much to complete and no angels, I’m afraid, to do the work for me, apart from a rogue of an apprentice named Angelo.”

Brother Bartolomeo laughed. “You need no angel,” said he: “God has given you all the talent required.”

Buonamico smiled and nodded in acceptance of the compliment.

Bávlos looked down at his plate sadly.“I will come back soon as well,” he said, “once Nieiddash has had a chance to get a little more good food in her.”

“You do that,” said Buonamico. “Come when you can. I will look forward to seeing you again.”

Bávlos thought that his friend’s eyes looked teary. But then he guffawed loudly and drank a large gulp of wine. “Wait till you see my San Bartolomeo!” he cried. “It is a painting to remember!”

The next morning at morning prayer, Bávlos and Bartolomeo stood by their friend as he unveiled his painting. Bávlos’s Madonna was already installed on the left side of the altar, on a stone pedestal that Brother Bartolomeo had fixed. He had picked some wildflowers to place before the statue. On the right side, Buonamico had created a tall and noble saint, stepping into the space from under a round arch. His head was turned to the side as if he were carefully attending to the altar. His hair and beard were flowing and white, and he visage looked the image of Brother Bartolomeo. He held a green book of prayer and a staff. But the most striking detail was at the bottom of the depiction, beside the saint’s feet. There, Buonamico had painted a fat pig.

“A pig?” said Bávlos surprised.“My way of saying thank you to the beast for a fine week’s eating,” said the painter smiling. “Anyway, lad, don’t you know the faith? ‘All you beasts, wild and tame, bless the Lord!’”