Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348

a free multimedia novel by

Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison

|

Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348 a free multimedia novel by Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison |

|

|

|

|  |

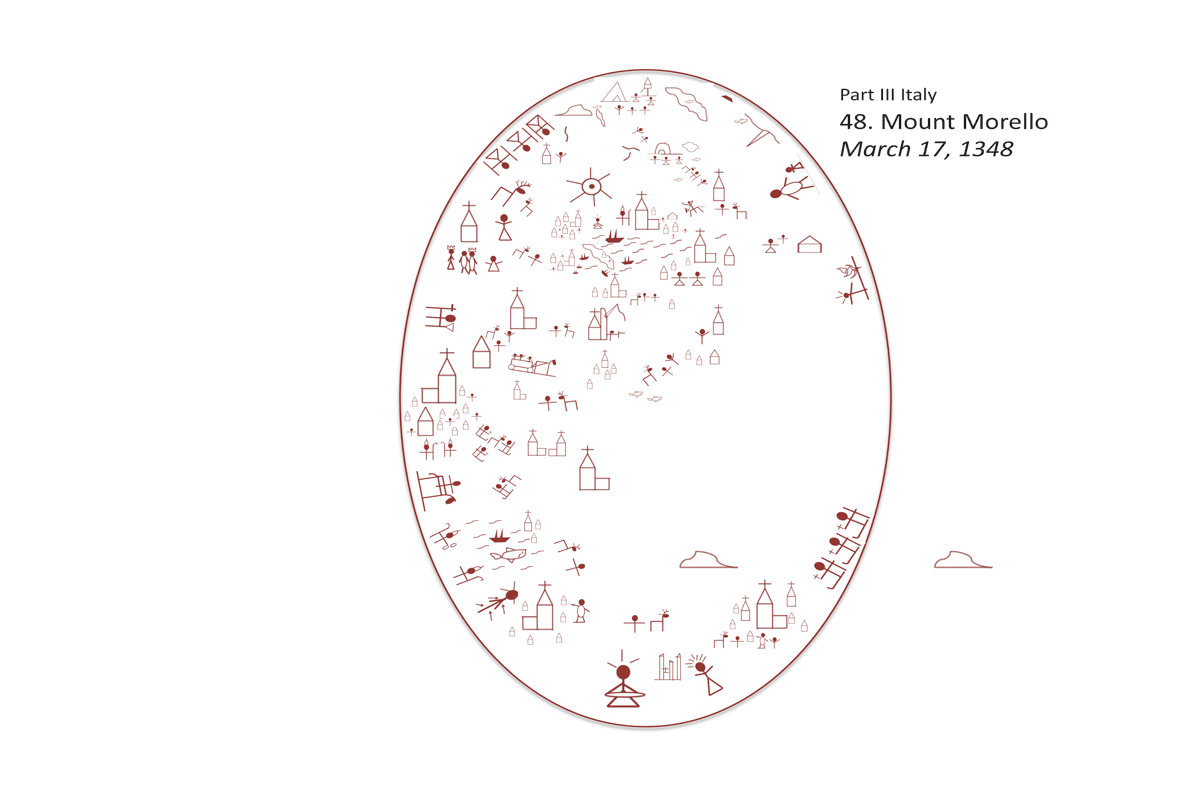

48. Mount Morello (March 17, 1348)

The After six days Jesus took Peter, James, and John his brother,and led them up a high mountain by themselves.

Ever since the night of their dinner with Master Simone, Buonamico had harped on the medicus’s strange pronouncements about Fenni and their culture. The event at the hitching post had excited a tremendous amount of discussion in the area, and people in Firenze had heard about the wonder within days of its occurrence. No one seemed to connect the event with either Buonamico or Bávlos, however, since the opinion abroad was that the beneficiaries of the miracle were a French pilgrim and his elderly servant. Given the circumstances, Buonamico did not choose to reveal the truth to his neighbors, and Bávlos seldom spoke to anyone in the city except when accompanying his master on some errand. To most people they met, Bávlos was just an apprentice, older than Angelo but not worth addressing directly.

Of the event at the hitching post, most people were certain that it was a miracle accomplished by St. Fina, on whose feastday it had taken place. Privately, however, Buonamico remembered Bávlos’s words about protective charms and seemed intent now to needle his friend about his exotic background at every turn, almost as a defense against the specter that his friend could be a sorcerer. Bávlos knew that his companion meant his remarks as jests, as conversation fillers intended to pass the time as the two worked together in the shop or at a painting site. But the constant jokes irritated Bávlos nonetheless, as did his master’s nearless ceaseless chatter.

One day, Bávlos was trying to bring order to the table where he and Angelo regularly ground the pigments for the paints. He glanced at a large pile of sketches Buonamico had made—more nude boys.

“Studies of a painting of a young Giovanni Baptista, you see,” said Buonamico impressively, his head quavering with self importance. Bávlos was skeptical. “Was he often nude this San Giovanni?”

“Very often,” chuckled Buonamico, “he practically lived without clothes, much like you Fenni in the North.”

“I don’t go about nude,” said Bávlos, bristling somewhat.

“More’s the pity,” murmured Buonamico, resting his fleshy hand on Bávlos’s shoulder and tickling his ear. It occurred to Bávlos that the face in Buonamico’s sketches looked very much like his.

“Listen,” said Bávlos, “If you want to know what Sámi life is really like, I can show you, but not here. You wouldn’t understand unless you come to truly know the countryside.”

“Nonsense! I know the countryside already,” said Buonamico in an affronted tone: “my friend Calandrino, fool though he is, has a small estate out there in Calenzano and—”

“No,” said Bávlos insistently, “I don’t mean going to an estate and living in a house that happens to be removed from the city. I mean living out on the land, in the countryside, on a mountain, like the Mount Morello that Master Giovanni told us of!”

“Whatever do you mean?” said Buonamico, now incredulous, “You mean, living out like an animal? Like, like-”

“Yes,” said Bávlos completing the sentence for him: “Like a Fennus. It is not a bad way to live, my friend.”

“Not a ‘bad way,’ I’m sure,” said Buonamico, “if you’ve got nothing else, but good God, Paolo, don’t you see the advantages to living a proper life?”

“You call this life proper,” said Bávlos testily, “but you don’t know the alternative. Where I come from the happiest of days are spent outside, in the air.”

“Where you come from, as far as I can tell,” said Buonamico disdainfully, “All your days are spent outside, even in the dead of winter!”

“Well, it’s not winter now,” said Bávlos, “and Nieiddash and I need to get out in the country for a while. Nieiddash is getting close to calfing, you know, and she needs better things to eat than we can provide for her down here.”

“So you mean to take yourself out to the wilds,” said Buonamico, “and you’d like me to come as well.”

“I am inviting you,” said Bávlos, “so that you can see the beauty of the life. You don’t have to become a Fennus, but wouldn’t you like to see what it is like to sleep in a truly peaceful place, with only animals about?”

“I don’t think one can be quite at peace,” said the painter uncharitably, “with wild animals about. But I recognize your sentiment and I appreciate your efforts. Under the circumstances, and to prove that I have no fear of the rugged wilds, I would be honored to accompany you into the wastelands. Where have you a mind to go? Shall we head for Mount Morello?”

“Yes!” said Bávlos eagerly, “That would be an excellent place.”

“Excellent indeed!” cried Buonamico. “As I mentioned, my friend Calandrino has a farm out in Calenzano. Not much of a place, but it does supply him with a pig each year. At any rate, we can ride there, leave our mules and head off into the mountain.”

“How far is it?” asked Bávlos. “Well, not more than seven miles from Master Giotto’s Tower of the cathedral,” said Buonamico. “An easy ride on an afternoon.”

“It seems close enough to walk,” said Bávlos, “and then we could leave your mules stabled back here.”

“Walk?! All that way?” cried Buonamico in disbelief. “My boy, painters don’t walk, they ride. I’m no pilgrim or vagabond you know. Oh.,” he said, suddenly feeling self-conscious, “I forgot that you are both of those things my lad.”

“Yes, well, if you want to ride that will be fine. But after Calenzano we must walk if we are to get into any good country.”

“Yes, yes,” said Buonamico, “if you insist.”

The men left early the next morning. It was not that early, truth be told: Buonamico insisted on a leisurely breakfast and had various errands to attend to before leaving. His neighbor had agreed to look after the livestock still at home and to keep an eye on Apprentice Angelo. But the friends left the city gates before the sun had gotten too high, in the cool of a moist and budding spring day.They started on a long and winding road, mostly paved with stone. Buonamico and Bávlos rode astride on the mules, while Nieiddash walked on behind, tethered to Bávlos’s waist. It was a pleasant day and people were out tilling and sowing.

“There’s a useful way to use the land, my boy,” said Buonamico nodding at some farmers: “Tilling the ground: forcing it to render up its treasures to mankind!”

“I suppose,” said Bávlos. “Where I come from the warm season is really too short for that sort of thing. There are still two or three months of snow left back home.”

“Yes. I suppose it would be hard to till soil under that much snow,” said Buonamico, smiling, “The ground must be frozen solid!”

“It is indeed,” said Bávlos.

“Then what do you do if you need to bury something?” asked Buonamico, frowning, “like, say, a body?” Clearly the Plague was on the painter’s mind, even if he never mentioned it directly.

“Well,” said Bávlos, “You can’t. You have to wait till spring. You can store the body in a box upon the earth or better yet, up in a tree or in a storehouse on a pole, where animals can’t get to it till the ground is thawed enough to work.”

Buonamico shuddered. The thought of animals reaching the remains of human beings was utterly repugnant to him.“I see,” he said tersely.

They arrived at Calandrino’s farm well before midday, but Buonamico insisted on staying to lunch. Calandrino had settled the farm upon his cousin, who lived there with his wife and children. There were eight children that Bávlos counted, but Buonamico assured him that there were more. “One thing they’re good at making out here in the country,” said Buonamico: “children.” The farmer and his wife received the friends graciously and shared their meal of chicken stew and bread. Then the friends left their mules, and taking Nieiddash on a line, they headed up a much smaller lane toward Mount Morello.

It was a warm afternoon and Buonamico was accustomed to nap after dinner, so the going was rather slow. The path turned smaller and smaller by degrees and grew steeper and more irregular as well. Where the road to Calenzano had been wide enough for two horses to pass easily, the lane here was a mix of stone and mud and scarcely wide enough for even a single wagon. It picked its way upward, skirted by a wall of stones that generations of farmers had extracted from their fields and used either to separate their fields from passers by or to buttress terraced fields. In many places the wall was five feet tall on each side of the lane. Bávlos noticed the tall, spreading trees visible above the walls. They had cool silvery green foliage, with narrow leaves of a waxy texture.

“What are these trees?” asked Bávlos.

“Why those are olives,” said Buonamico. Bávlos had often eaten olives and tasted olive oil—staples of life down in Firenze—but he had never known the tree from which the fruit came. Looking at the trees, he found them fascinating: massive ancient trunks that were hollowed out with rot and which nonetheless put out abundant shoots. It was as if the trees simply refused to die, despite the best efforts of tormentors.

“How these trees struggle to survive!” said Bávlos.

“Indeed they should feel very guilty,” said Buonamico. “Their fruit is putrid when first picked. You have to cure it in salt for weeks and weeks before the wretched things even begin to approach being edible. If the result were not so fine, I would personally be in favor of cutting the whole lot down forever.”

“But surely you are grateful to the olives,” said Bávlos smiling.

“Grateful? How so?” grunted Buonamico. “The olives do nothing for mankind and we do everything for them. Look at these terraces: all the work that has gone into giving these trees a home, all the pruning, all the tending. Then all the picking in the fall, and the squeezing or the brining. I don’t think there is much to be grateful for!”

“I see,” said Bávlos. In his own land, one would never speak so ill of a plant or an animal that supplied so much good to the human community. It seemed shockingly ungrateful and also somehow irreverent. “Still, I think they are fine trees for what they give us. I would be very glad if we had such trees back home.”

“Have you no olive trees there either?” said Buonamico, shaking his head.

“No, we don’t,” said Bávlos. “We do have lots of pine trees, of course, and we make a fine porridge from the inner bark of such trees, harvested from just one side of the tree so that it will recover.”

“Ah pinebark,” said Buonamico. “Sounds little better than deer forage.”

“I suppose it’s not,” said Bávlos. “I don’t think we try to be better than deer—being as good as deer is enough for us.”

The friends climbed onward past a fortified tower, manned by the city of Firenze to warn of invading armies. They waved at the soldiers, who were sitting in the upper gallery of the tower under a round arch. “Travelling through?” they called.

“Yes, just so,” called Buonamico back. He did not want to call attention to the fact that they were planning to camp nearby.

They crossed a ravine on a little bridge, looking at the roaring stream below. In the abundance of the spring rains the brook was full and rapid, making a lively but somehow soothing sound. Bávlos was happy to listen to the sound of the water and to be in the countryside again. It was like a music that he knew and loved but had not heard for a very long time. It sounded simple but honest, artful but not artifaced.

Gradually the fields ended and the friends found themselves surrounded by forest. The trees were mostly pine and tall narrow evergreens that Buonamico called pioppo nero, as well as oaks and other hardwoods. There were abundant birds in the branches above, communicating the presence of the travellers to each other in sharp warning calls and flying from branch to branch to keep an eye on them. It was nesting season, and the birds were more attentive to passers by than usual. The branches filtered the strong light of the afternoon and kept the lane cool and shady. Toward late afternoon, Bávlos began to look for a place to set up camp. After a little scouting, he found an ideal site: a good dry stand of pines near a waterfall well away from the little lane. The waterfall was breathtaking: a narrow crack in a rocky cliff led into what seemed like a tiny roofless church. Above, at a height of some five men tall, Bávlos could see the stream leaping off its bank and launching into a graceful fall into the cavern. At the bottom of the little space, the water splashed playfully into a small round pool before running out of the cave and into the sunshine of the hillside. The light in the space was filtered and gentle, as if one were seeing through a tangle of roots from the trees that ringed the opening above. Bávlos noticed a niche in the cavern wall half way up. No doubt the seeping water had tunneled out this place over the centuries and now it stood as a tiny lookout over burbling water below.

“I shall carve a statue to sit in that place,” said Bávlos to himself. He cupped his hand and drank some of the water from the pool. It tasted fresh and cool. He left the cavern quietly and hurried out to set snares and traps nearby while the light was still good. Buonamico, meanwhile, had settled heavily down in the pine grove to rest.

He retrieved a winesack from his pack and drank a long swig of wine.“Water,” he muttered. “What’s wrong with wine?”

At twilight, Bávlos managed to shoot a young roe deer, which he happily carried back to camp gutted and ready to skin. He had already retrieved his arrow from its side. At camp he quickly began to skin the animal, cutting pieces that he placed on spits to cook over a smoky fire nearby. “We shall eat good meat tonight!” he said cheerfully.

“We shall eat gamey meat tonight!” grunted Buonamico. “Barely edible, no doubt.” Nonetheless, when the pieces were cooked, Buonamico ate heartily and with good humor. “It is pleasant to spend the hours out here,” said Buonamico, “beneath the trees and stars; I can see how you would miss it in the city.”

“For me it fills a void to be here,” said Bávlos, “It is like being with an old friend again.” Bávlos created a small shelter for the two men: a raised platform covered with pine branches underneath which they stretched out for the night. Bávlos carefully banked the coals of the fire so that he could rekindle it the next morning.

Buonamico slept fitfully. The ground that had seemed so soft at the beginning of the evening somehow felt like stone by night. And worse than that, jagged rocks and sticks seemed to work their way up into the painter’s back. There were strange night sounds too, owls and chirping noises and tramping in the forest, as well as the constant irksome babble of the nearby stream. Toward morning, however, the painter fell into dreaming. He dreamed again of being a bird. He was flying high in a pristine blue sky. Far below he could see Mount Morello: its terraced olive groves, its occasional tiny houses, its wandering paths and thick forest. He was looking for someone, peeling his eyes to catch sight of his master. At once he saw the man raise his arm and so, folding his wings, Buonamico dove. As he came nearer, he saw that it was the same man he had seen before in his dreams, a handsome man with eyes of blue. But now he recognized the man as Bávlos, and he saw that he was not clad in mailshirt but in a leather tunic. Instead of sitting astride a horse, he stood on his own legs, with a reindeer close behind him. “Come my good friend,” said the man. Buonamico felt an irresistible desire to perch on the man’s arm and he did so promptly. All was as it should be. But then something changed. The man was not hooding him as he should after a flight, but was untying his jessies. Why was he doing that? What was this man up to?

“You don’t need these things, my friend. Fly free.” He lifted his arm to launch the bird into flight. What did he mean ‘Fly free?’ Why had he removed the jessies? Without those it was impossible for a falconer to retrieve or control a hawk. Buonamico felt himself circling higher and higher over the man’s head, looking for instruction, waiting for a cue. The man simply spread his arms wide and upward, as if to say “Take, it is yours.” Then he turned and walked away.

Buonamico awoke testy and unsatisfied from his first night’s sleep on the mountain. His back hurt and he felt unpleasantly moist all over. Birds were chirping incessantly and it was cold, terribly cold. He sat up to see Bávlos working over the fire. He had caught several quail in his snares over night and was busily plucking them for breakfast. “Good morning!” he said cheerfully.

Buonamico grunted in reply, conscious of his disagreeable behavior but not able to suppress it still the same.

“Today I am going to work on some larger traps,” said Bávlos enthusiastically, “to see if I can catch us something bigger.”

“Quail is a fine breakfast, I must admit,” said Buonamico, trying to be solicitous. “What shall we do today?”

“Well, I thought we might tramp a little farther in the area and see what things there are to see,” said Bávlos. “And then I want to start carving a figure for the waterfall.”

“A waste of art, lad, a waste of art. Who on earth will see a carving in that little cave?”

“I don’t know,” said Bávlos, “Iesh, of course, or the Virgin, and maybe the water and some birds, perhaps a fox?”

“Lad, you puzzle me,” said Buonamico. “Do you not understand yet that the faith is a gift of the Almighty to men (and, at least occasionally, to women too) and not to beasts and creatures?”

“I know that’s your view,” said Bávlos, “but it doesn’t seem that way to me.”

Buonamico remained sulky and silent for much of breakfast. Bávlos seemed perfectly contented by the silence, which only irritated his friend more. “Is there no such thing as polite conversation out here in the wilderness? Must we behave as animals even as we eat and sleep like them?"

“Oh, I’m sorry,” said Bávlos. “In my land, truly good friends say little to one another.”

“Rudeness among friends.”

“I suppose,” said Bávlos; “we think of it as ‘openness’ among friends.”

“How on earth can you be ‘open’ if you don’t say anything?”

“Why, I guess we mean that we are open to simply being ourselves, even when that means being quiet.”

After breakfast, Bávlos when to check on Nieiddash, who was foraging well in the area. Now Bávlos was glad that Nieiddash didn’t need to be tethered. She simply preferred to stay nearby, thinking of Bávlos as part of her herd. She was the right reindeer to have brought on this journey. Nonetheless, when the men prepared to take to the road again, Bávlos put her back on a lead, so that he could keep her nearby as they proceeded through the forest. The two men continued along the lane as it threaded across the other side of the little valley and then looped toward the far side of the mountain. They came onto more fields, now far less tended: pasture areas for livestock, with an occasional farmhouse and once in a while a small stand of olives.

In a deserted area close to the lane and overlooking the valley, they found a tiny church. Its front door lay not on the roadside but at the chapel’s far end, facing out into the valley. From the front of the church, on a little terrace that separated the church from the steep slope of the hillside, they could see a vast sweep of landscape: green fields, vineyards, and olive groves far below and smoke rising from little houses dotting the landscape. Beyond the lowlands, hills arose abruptly, and behind these, distant jagged mountains loomed, still with a little snow on their crests. Those were true mountains, days’ and days’ riding from here; this little mountain was only a hill. Yet the view it offered was magnificent nonetheless.

Far in the valley, obscured by a midday haze, Bávlos could just make out Giotto’s tower and the walls of the city from which they had come. They turned to look into the church, kneeling and crossing themselves before stepping to enter. The doors had been opened wide and Bávlos saw that they supplied the main light in the little building. The only window was a narrow vertical fissure on the rounded wall directly above the altar. Bávlos loved chapels like this: they did not have the partition that separated priest and altar from the faithful, and they seemed to remove the many layers of formality and hierarchy that characterized the larger, finer churches of the city. Here a person could feel one with the altar and with the mass, as in a noaide ceremony back home. Bávlos saw that the church was devoid of any artwork: nothing but gray well cut stones for wall and floor and a simple roof of beams above. Only around the altar had someone painted a blue sky studded with a regular pattern of evenly spaced stars. Bávlos sighed in happiness. He heard someone come in behind.

“Greetings my friends!” said the man. Bávlos could see that he was a monk: he was dressed in a black habit with a rope belt. He wore no shoes. “Welcome to this chapel of San Bartolomeo. I would be happy if you would join me for mass and lauds.”

“Certainly,” said Bávlos. The mass was simple but moving. The monk, tall and lean, with shaggy white hair and a long beard, chanted the prayers in a simple and clear manner and he shared the Eucharist with Bávlos. Buonamico declined to receive the Eucharist but seemed contended with the service. Bávlos noticed him busily eyeing the walls as they stood side by side, no doubt envisioning the art that would suit each space and the time and materials they would require. After prayers, the man invited the visitors to his hut nearby. Bávlos said that he would gladly come, but that he had to attend to a matter back in the forest first. He walked away at a brisk pace while the other two men turned toward the hut to visit and talk.

About an hour later, Bávlos returned, carrying the carcass of a wild boar on his shoulders. “Dinner!” he said delighted.