Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348

a free multimedia novel by

Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison

|

Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348 a free multimedia novel by Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison |

|

|

|

|  |

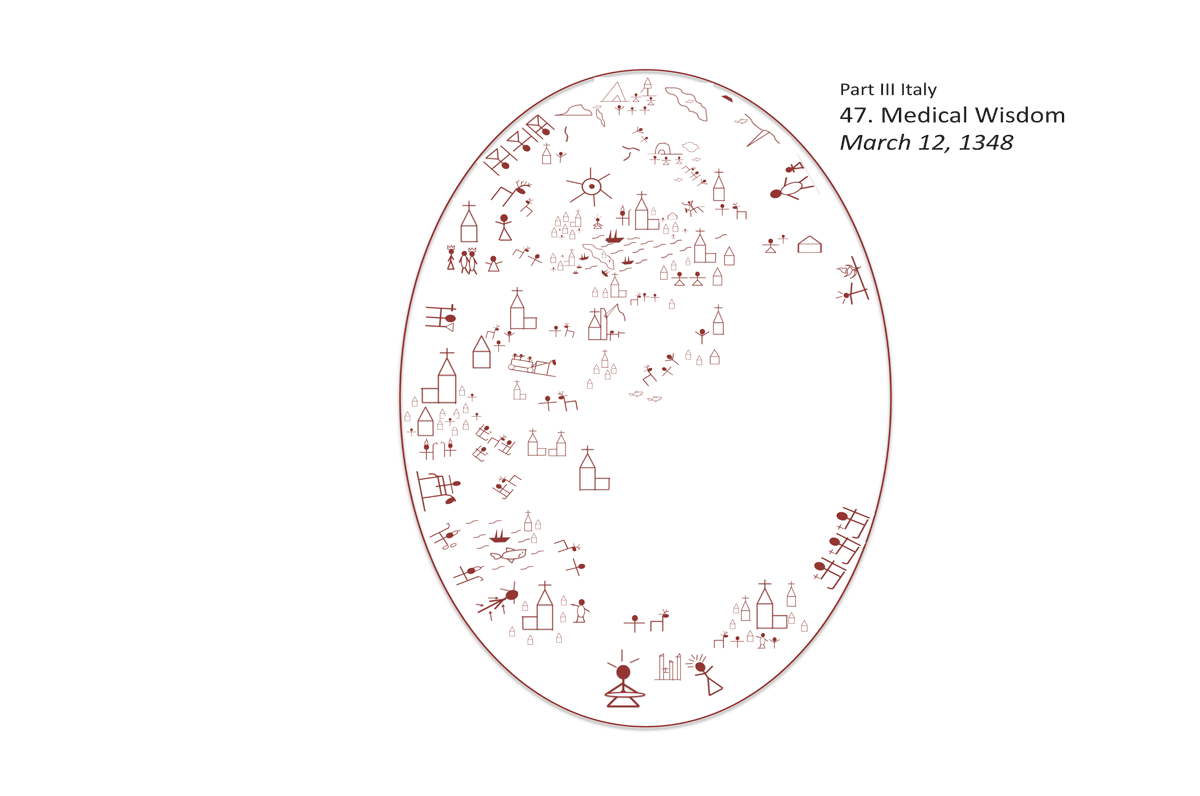

47. Medical Wisdom (March 15, 1348)

Lord, have pity on my son, for he is a lunatic and suffers severely; Often he falls into fire, and often into water. I brought him to your disciples, but they could not cure him.

Bávlos’s meeting with Master Simone had not been what he had expected. The dinner had been amusing, to be sure, but the discussion of Master Tacitus’s book decidedly frustrating, even unpleasant. Not only had Bávlos had to endure hearing his people described in a strange and inaccurate way, but he had also learned nothing of the manner that healing occurred in Italian society. This topic interested Bávlos considerably, especially if he was going to have to honor his promise to Buonamico and cure him should Ruto arrive.

Reports were now frequent that the supernatural repercussions Bávlos had predicted in Pisa were beginning to take place at an alarming rate in cities all over the region. The stories were always like Master Giovanni had related: People found hard purple knobs like peach pits or hen’s eggs, growing in their groins, armpits, or breasts, and these often eventually burst open, spreading puss and blood. For others, the blood came out through the lungs: they coughed endlessly, until their spit was bright red and then they died. Many became speckled with markings, like the flecks of brown on a rabbit as spring approached. Often they felt seized by a raging fever, during which they saw visions of the sins of their lives and the excesses of their past behaviors. Scores of people had reportedly died in other cities, although Ruto had not yet come to Firenze. It was said that so many had succumbed in those places worst hit, that the gravediggers and priests could not keep up with the work of burying them all: now they simply dug deep trenches, piled the corpses in with a few words of blessing, and covered them with soil. As soon as the trench was filled, they had to start on another, because the dying would not cease. Buonamico did not like to discuss the matter, at least not with Bávlos, who always brought up the Camposanto as the culprit in the situation. But Ruto was on the rampage now, and everyone was fearful of where he would strike next.

Bávlos wanted to learn about the healing arts of this land before it was too late. If the disease hit, he wanted to know as much about all methods of healing as possible.“Where can I learn more about the work of medici?” asked Bávlos.

“They belong to my guild,” said Buonamico proudly, “The Arti dei Medici e Speziali, a brotherhood to which you are not admitted.”

“I see,” said Bávlos. He had heard Buonamico speak often of his guild and he was a little ashamed that he still didn’t have the slightest idea what he was talking about. With a tone of defensiveness, he said in response: “I simply want to know what medici do here in Italy and how it compares with what we do for the sick back home.”

Buonamico laughed. “Ho! My boy, there is no comparison between that art which the greatest minds of our day have developed here and the crude efforts at healing that can take place in a land such as yours! Do you not know that Firenze is recognized as among the very finest places for the medicinal arts in all the world?”

Bávlos sucked his teeth. There was little one could do about such expressions of superiority in this country: they were as impossible to counter as they were untrue. Buonamico knew nothing of the healing of Sámi noaidit, and yet he was certain that the medicine practiced by people like Master Simone—a dimwit by Buonamico’s own description—was far superior. One could not argue with such prejudice: it was simply part of daily life here, and he had come to expect it.

“Nonetheless,” he said at last, “I would gladly learn what these superior practices are so that I can report them to healers back home and convince them of their errors.”

“Ah, well then, “ said Buonamico, “you will want to go to the Cloister of the Dominicans here by the church of Santa Maria Novella. They are known as the finest medici in our city and the greatest pharmacists too. I know several friars from a commission I painted in their refectory once. I will introduce you to Brother Pietro if you’d like.”

“Yes, that would be wonderful,” said Bávlos. Now he would have the chance to find out what he really wanted to know. Not many days after, Buonamico escorted Bávlos to the Cloister of the Dominicans. The men were ushered in to a large and peaceful cloister area: a small pad of garden surrounded on all sides by a colonnaded walkway. The walls of the friary ringed the garden entirely, secluding it from the outer world. The sun shone warm and pleasant into the garden, while the columned pathways were shady and cool. Bávlos had a sense of tranquility and wellbeing in this little courtyard, which contained various herbs, several small trees and a central well. What struck him most about the place, however, was its smell: the air was heavy with a sweet and aromatic odor that seemed to permeate every inch of the grounds.

Buonamico’s friend Brother Pietro greeted them in the garden. Bávlos was struck by the friar’s habit: it was the same white and black combination that Brother Pekka had worn back in Bávlos’s homeland so many months ago. “Brother Pietro,” inquired Bávlos, “Are there members of your order in the north?”

“We are everywhere,” said Brother Pietro with a smile of knowing pride.

“In the far north as well?” asked Bávlos. “Indeed, even there. Our order has a province of Dacia that serves the northern periphery of our world. Our holy founder San Domenico traveled to Dacia once before founding the order and he held it as a sacred task that our brotherhood should share the light of God with that heathen realm.”

“Dacia,” thought Bávlos. Yes, that was what Sámi often called the strangers. So Pekka and this Pietro must be of the same order! Hopefully, though, Pietro was a littler swifter than his brother to the north; he certainly seemed so thus far.

“Good Brother Pietro,” said Buonamico, getting to the purpose of their visit. “Young Paolo here, although not yet of our guild, would like to learn a little of the theory of modern medicine. He is hopeful that learning a little such wisdom will allow him to convince the healers of his homeland of their error.”

“Indeed?” said Brother Pietro with a sage nod, “That is commendable, young sir Paolo.”

“Good Brother Pietro,” said Bávlos, “can you tell me what is the cause and treatment of disease?”

“Let me ask you this,” said the friar, searching for a vehicle to convey his understandings to Bávlos. “Imagine a piece of bread, pure and white, cut from a loaf baked just this morning. Can you imagine that?”

“Yes, certainly,” said Bávlos. “Now imagine that I place that slice of bread on a plate here in the garden, in this sweet and wholesome environment, leaving it thus for the day. At the end of the day I bring the bread inside and taste of it. What shall I taste?”

“Well,” said Bávlos, “I should expect that it may have picked up some of the taste and smell of the garden. It would be like smoking fish: the fish acquire the taste of smoke.”

“Indeed, excellent!” cried the friar. “You are an intelligent man, I must say. Now,” he added, his eyes narrowing, “what if I took a second piece of the bread and placed it on a plate, and brought it in the direction of Santa Maria della Scala, close to the convent of San Jacopo di Ripoli. You know the place?”

“I do,” said Bávlos. There was a long trench there where all the people hereabouts went to dump their chamberpots, and it smelled worse than anywhere Bávlos had ever been.

“Well,” said the friar. “We leave our piece of bread there for the day and then return to collect it toward evening. How do you think said piece of bread will taste after this treatment?”

“Foul,” said Bávlos, shuddering.

“Even so,” said the friar triumphantly. “Do you see what happens? The smell and putridness of this place contaminates the bread just as the sweetness and beauty of this garden can uplift and make wholesome a slice of the very same loaf. We medici call this process contagion.”

“Contagion,” said Bávlos impressed. “So then, worthy friar, how do you use this insight to cure disease?”

“Well may you ask that question,” said the friar, “and well may I answer. What is it, you suppose that causes disease?”

Bávlos hesitated. He knew what he had always heard in his homeland: disease is caused as the outcome of evil acts, or by the arrival of an evil spirit. Lesser maladies were often the result of improper behavior, while greater ones tended to be caused by the assault of an unseen spirit who had to be expelled through healing acts. But how did this understanding mesh with this man’s ideas of smell and bread? “I don’t know,” he said at last, “contagion?”

“Yes, yes, that’s it!” cried the friar jubilantly, “Contagion! Do you not see? If I spend my days in places of iniquity, of mire, of bloated, smelly death, that contagion will enter me as well. I will become ill and eventually die. But,” he said, gesturing about him with eyes wide, “If I surround myself with all that is sweet and pure, will my body not also acquire this healthfulness from its environs? I ask you, is that not true?”

“Well,” said Bávlos, “I see your point.” It was a persuasive view, to be sure, yet it seemed to miss something that was central to the Sámi way of healing.

“But then, what do you do once the disease has struck?”

“Well,” said the friar gravely, “at that point there is little one can do. The best one can hope for is that a sweet and fresh environment may cause the unwholesomeness that the body had acquired through contagion to dissipate. Think of it like the sweet incense of high mass: the pure and salvific fragrance of the incense wafts across the sinful and purges them of their iniquity. So, too, we make fine elixirs and balms that purge the air of its unwholesomeness and lead the body back to health.”

“Ah,” said Bávlos, “so your medicines do not try to attack or kill the disease?”

“No,” said the friar, “they displace it! Take the Plague, for instance—” Bávlos winced at the name. In his experience one should never discuss a disease by its name, unless one wanted to attract it. In his mind’s eye he saw a black-clad Ruto start at the mention, turning his horse abruptly to head in the direction of the conversation. “The Plague,” said the friar, oblivious to Bávlos’s reaction, “is the result of foul airs. Thus a superabundance of sweet rose water, breathed in with ample measure of other aromatic plants, will go far to counteract its effects. Provided we keep our world smelling sweet,” he said with a flourish of the hand, “we are indemnified from that scourge.”

“Not likely,” grunted Brother Giraldo, who had now joined the party. Brother Pietro rolled his eyes. “I had meant to shield you from this, friend Bávlos, but you may as well know. Our house is subject to some controversy on this matter.”

“Controversy indeed!” snorted Brother Giraldo. He was younger than his colleague and spoke with a somewhat foreign accent, Bávlos thought. He was stocky and red-haired, with abundant freckles on his cheeks and a pink hue to his skin. “We are in the midst of a struggle between quaint misconceptions and the truth!”

“I take it that you mean to refer to your own theories as the ‘truth,’ in this case?” said the older friar.

“I do,” said the younger, “and they are not simply ‘my’ theories: they are the consensus of all the truly gifted medical minds of our day, based on understandings that derive from the greatest minds of all time: Hippocrates, Theophrastus-”

“Pray, then,” said his senior colleague, “in the spirit of clerical debate, present your case to this visitor from the distant reaches of Dacia.”

“Gladly,” said the friar sitting down with knees wide and eyes darting from face to face. “To wit. Tell me, good stranger, what difference there is between garlic and butter!”

“Between garlic and butter?” said Bávlos, confused. “There are many differences, I think.”

“Yes!” cried the friar. He seemed as enthusiastic in expounding his theory as his colleague had been before him. “There are differences! And what causes these differences, I ask?”

“Well,” said Bávlos, perplexed, “they are different things: garlic is an herb that grows in the ground and tastes sharp and powerful. And butter is the product of work done on milk. It is sweet, depending on the amount of salt you add.”

“Precisely!” smiled the friar, apparently very satisfied by this answer. “So they are. Their differences—so palpable to us, so distinctive in every way—these differences, I say, derive directly from what the two things are made from. Is it not so?”

“It is,” said Bávlos.

“Well, then, we may ask the question: Just what are these things made of? Do you see? We are looking to get beyond the surface, beyond the mere fragrance level—” he said the last with a sidelong look at Brother Pietro and a certain sneer in his lip—“toward the really essential, underlying level!”

Bávlos found the friar’s delivery exciting. He felt in the presence of a very great mind, someone who could see, as he indicated, beneath the surface of things.

“It is at this level,” said the friar impressively, “that we discover not only that which distinguishes garlic from butter—in other words, that which makes them different from each other—but also that which makes them the same!” He said the final word with great intensity, leaning forward, his eyes flashing. Bávlos was more surprised than ever.

“The same?” he said.

“The same!” said the friar with a noble wave of his hand. “You see, it is like this: each of these things, the garlic and the butter, and indeed you and I as well as the rest of God’s creations, are made of differing precise combinations of four prime elements—earth, air, water, and fire!”

“Earth, air, water and fire?” Bávlos repeated, staring.

“Yes!” said the friar, “Let me explain.” Brother Pietro was now shaking his head slowly and looking up to heaven. His gesture seemed to provoke Brother Giraldo greatly. “Do you not notice something sharp when eating garlic: something biting, something hot?”

“Of course I do,” said Bávlos. He remembered the first time he had tried the herb and the tears it had brought to his eyes. There were no such foods in his homeland, except for the stinging plant gáskálas, which despite its cruel biting tendency was good to eat in the early spring.

“Well that hotness which you taste,” said the friar, “is due to fire. There is a high measure of fire in garlic. And have you noticed that butter does not have this heat, but rather a coolness, as of wind and rain?”

“Yes, I suppose,” said Bávlos. Butter certainly did taste wet to him, at least.

“Well,” said the friar, “then we know that butter is high in respect to water and air content. You see, in the same way, every single being in God’s universe (apart from angels and other immaterial, purely spiritual beings, of course), are made from different combinations of earth, air, water, and fire. And when we grow ill, it is because we have ingested foods that throw this divinely ordained balance out of order. An overconsumption of firey foods leads to fever, leprosy, eruptions of boils. Overconsumption of watery or earthy foods lead to chills, swellings, and the like. It is the task of the medicus not to drown out odors,” again he glared at Brother Pietro, “but to restore bodily balance, caused through unwise consumption.”

“And these four elements are in us as well?” asked Bávlos.

“They are!” cried the friar. “We can sense them in the bodily humors our body exudes.”

“Bodily humors?” asked Bávlos.“Yes,” replied Brother Giraldo. “These are, to wit: black bile, imbued with earth; yellow bile, imbued with fire; phlegm, imbued with water; and blood, imbued with air.”

“Indeed?” said Bávlos. He did not know what fluids this man was referring to exactly, and he certainly couldn’t quite figure out how blood related to air, except through wind-knots, of course.

“Yes, yes,” continued the friar. “We must try to keep ourselves in balance, even if in fact we will each be ruled by one humor above the others.

“How so?” asked Bávlos, again fascinated.

“Are you not an artisan?” asked the friar.

“I carve wood,” said Bávlos tentatively.

“Indeed,” said the friar, “I can see it about you. You are a sanguine type: warm and hopeful, courageous and at times amorous as well. You are dominated by blood, and blood is dominated by the air of which it is composed.”

“I see,” said Bávlos. He found the description flattering, although he still did not quite understand the link between blood and air.

“Now your friend Buonamico—”

“Leave me out of this!” said Buonamico, crossing his arms and frowning.

“Your friend Buonamico I should say is of the melancholic type. He is prone to sleeplessness, irritability, even despondency at times. And yet he is a fine guardian of his friends and his profession. He is an artist and the great thoughts of his calling weigh heavily upon his mind.” Buonamico nodded at the characterization which seemed to please him a great deal. It did not seem particularly accurate, though, as far as Bávlos could tell.“He is dominated by black bile, the earthy essence of the spleen.”

“I see,” said Bávlos.

“Now my Brother Pietro here,” said the friar, “is choleric. He is governed by his liver and his humor is thus of the yellow bile. He is an idealist: temperamental and prone to heat.” Brother Pietro fumed, as if in demonstration of his colleague’s statements.

“And I, at last, am of the phlegmatic humor: calm, rational, and free from emotional impediment. I am governed by water, you see.”

Again Bávlos nodded. “But, again, worthy Brother, tell me how this wisdom can be used to heal the sick.”

“Why,” said the friar, his eyes wide, “it should be obvious! Balance, man! You must achieve balance! A bilious firey character like Brother Pietro here, must endeavor to avoid those foods replete in fire. Too much such food and his balance will tip from the point at which it merely colors personality to the point at which it destroys health.”

“So one treats disease through what one eats,” said Bávlos.

“You prevent disease through what you eat, sir, and you restore health through compensating in your diet. Beyond this it is impossible to ‘treat’ disease.”

“Ah,” said Bávlos. At least on this point it seemed that both friars were in agreement: disease could be avoided but not actually driven away. “I see.”

“Prayer,” said Brother Geraldo sagely, “prayer is your means of curing disease once it strikes. Is it not so in your country?”

“Well,” said Bávlos hesitantly, “among my people sickness is understood quite differently.”

“Do tell!” said Geraldo, now eager, “I should very much like to hear what you mean.”

“Well,” said Bávlos, “I realize that my people have not had the very great benefits of libraries and books of medicine, and centers such as this one. We have had to work out cures for ourselves, and these may seem strange or even wrong to you. But nonetheless, I have seen great illness cured, and through the actions of a healer no different than you or I.”

“How so?” said Geraldo, leaning forward with keen interest. Bávlos noticed that Buonamico had pushed back in his seat with an amused smirk. Brother Pietro had seemed to lose interest in the conversation altogether: he was looking up at the sky and mumbling to himself, pressing a rose petal to his nose.

“Well, for my people,” said Bávlos slowly, “Disease is said to come from two chief causes. One kind comes as the result of misdeeds or conflicts with others, be they human or spiritual. The other comes of its own accord and invades the body, taking it as its own.” There was, of course, a connection between these two, but Bávlos thought better than to explain to these men the ways in which diseases could be sent upon others as an aggressive act. They would see the Sámi as demonic and that would be the end of the discussion.

“My goodness,” said Geraldo, listening intently.

“Yes, so,” said Bávlos, warming somewhat to his topic, “if the disease comes from a conflict, you must set the matter straight: find out who is angry or sore or insulted and restore good relations. There are various ways to do so.” He deemed it again unwise to describe the practice of making sacrifices; such things never seemed welcome among Christians. And the idea of a noaide entering a trance in order to discover who was upset seemed far too hard to explain. Instead he tried to simply sum it all up, saying: “When a person is in harmony with all around him, he is less likely to grow ill.” Bávlos drew another breath and proceeded: “If, on the other hand, the disease has come on its own, you must force it to leave the person’s body. It is important to keep the person removed from others, so that the spirit of the disease cannot simply jump from one body to another during the treatment. And those who act as healers must be sure to disguise their voices and conceal their names, so that the disease will not know who is before him and take possession of them as well.”

The men were smiling now. “But surely,” said Brother Pietro, “You don’t mean that you banish the ill from among your company? That hardly sounds charitable to me.”

“That is so,” said Bávlos, remembering a similar criticism from Master Simone. “It can seem uncharitable. But the spirit living inside the ill one will be able to enter others unless such distance is gained. For the good of all, it is important to keep the ill from close contact with the rest of the community.”

More smiles from the men. Bávlos continued.

“Then the healer talks to the disease: he tells it that it must leave, that it has a better place somewhere else. And sometimes he offers the disease a reward for leaving: food or some other gift.”

“A sacrifice,” said Brother Geraldo nodding.

“Yes, I suppose,” said Bávlos. He guessed that he would not be able to convince them of anything now. The thought seemed to free him, and he continued: “Sometimes the healer gives the ill one foods to eat that drive out the disease: foods that the particular spirit cannot abide. These foods are given over and over again, along with plenty of rest and sometimes rubbing of the body. And if the healer is powerful, then he can force, or coax, or even trick the disease into leaving, and the person will be cured.”

Bávlos’s explanation was greeted with delighted and incredulous guffaws from all three men. Buonamico was shaking his head with laughter, wiping tears from his eyes. Brothers Geraldo and Pietro were looking at each other with newfound amity, their differences of opinion dwarfed by the immensity of the ludicrousness they now beheld in this stranger from distant Dacia.

“You are fortunate, friend Bávlos” said Buonamico as he rose to end the discussion, “that you have come to Italy. With healing like that in your country it’s a wonder any of you ever survive!”