Part III. Italy

Chapter 47. Medical Wisdom [March 15, 1348]

Cultural Explanations

|

Part III. Italy Chapter 47. Medical Wisdom [March 15, 1348] Cultural Explanations |

|

|

In this chapter Bávlos learns about medieval European medical theories. |

| Pharmacy and Basilica, Santa Maria Novella |

In this chapter, Bávlos learns about the medical science of fourteenth-century Italy, comparing notes with the healing traditions of his own country. His views are laughed off by the learned friars as ludicrous and cruel. Yet they are in some ways closer to modern understandings of disease than anything believed by medieval medici at the time of the Plague.

As a context for this chapter, it is useful to see what Boccaccio writes about the contagiousness of the Plague in the introduction to his Decameron. I reproduce the pertinent passages here from an online edition of the 1903 Riggs translation:

Moreover, the virulence of the pest was the greater by reason that intercourse was apt to convey it from the sick to the whole, just as fire devours things dry or greasy when they are brought close to it. Nay, the evil went yet further, for not merely by speech or association with the sick was the malady communicated to the healthy with consequent peril of common death; but any that touched the clothes of the sick or aught else that had been touched or used by them, seemed thereby to contract the disease. So marvellous sounds that which I have now to relate, that, had not many, and I among them, observed it with their own eyes, I had hardly dared to credit it, much less to set it down in writing, though I had had it from the lips of a credible witness. I say, then, that such was the energy of the contagion of the said pestilence, that it was not merely propagated from man to man, but, what is much more startling, it was frequently observed, that things which had belonged to one sick or dead of the disease, if touched by some other living creature, not of the human species, were the occasion, not merely of sickening, but of an almost instantaneous death. Whereof my own eyes (as I said a little before) had cognisance, one day among others, by the following experience. The rags of a poor man who had died of the disease being strewn about the open street, two hogs came thither, and after, as is their wont, no little trifling with their snouts, took the rags between their teeth and tossed them to and fro about their chaps; whereupon, almost immediately, they gave a few turns, and fell down dead, as if by poison, upon the rags which in an evil hour they had disturbed.

The reality of the Plague, with its highly contagious nature and mysterious etiology, would challenge utterly the medical understandings of 1348. In our chapter, however, this watershed confrontation has not yet occurred, and the learned friars are each secure in their contending theories of disease causation and contagion.

The apothecary at the Dominican friary of Santa Maria Novella dates from the medieval era, although it did not emerge as a paying pharmacy until the seventeenth century. The buildings and grounds of the friary are still used as a showroom and store and are a favorite site of tourists. Open the door to that building and you will smell literally centuries of thick sweet fragrances, the medicines of the past and today's perfumes and poupourri.

The notion of corrupting odors as a source of disease was popular in 1348 (and well into the nineteenth century) and stemmed in part from empirical observations. People noticed that patients became ill when exposed to "corrupting" environments like swamps or latrine pits and drew the conclusion that it was the odor that had sickened them. (Note that we still speak of "sickening odors" in English.) Later epidemiology would lay the blame for swamp-related diseases like malaria on mosquito-borne microbes, but such a theory had not yet developed in the fourteenth century. The fact that the Plague was carried by flea-borne microbes was also far beyond the ken of anyone living at the time. The apothecary at Santa Maria Novella became famous for its sweet-smelling concoctions, designed to drown out all unwholesome odors.

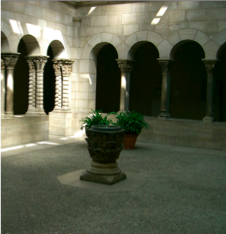

Maintaining salubrious air was one of the purposes of the enclosed gardens at the center of medieval monasteries. These cloister spaces allowed monks or nuns to meditate under the protective shelter of the house. At the same time, by the fourteenth century, they had become places for the cultivation of flowers and medicinal plants, arsenals of the healing fragrances that offered salvation from corrupting odors.

|

|

||

|

|

Brother Geraldo's competing idea of bodily humors and maintaining an ideal balance between them ("Humorism") was developed by the ancient Greeks and remained important throughout the medieval era. Hippocrates (460-370 BCE) was generally regarded as the originator of the theory, but Galen (131-202 CE) was important in its widespread acceptance throughout the medieval era. By the fourteenth century, learned academics were becoming more and more attracted to Classical thought, and Geraldo is one such scholar. For him, the veracity of his theory is born out by the fact that learned sages of old had developed or espoused it.

Quitessentially, neither friar regards actually curing a disease as entirely proper. One can prevent disease, but to attempt to cure it is to try to thwart the will of God. This distinction created a major stumbling block for those interested in the healing professions, most of whom were clerics at this time. Healing could be viewed as a kind of hubris or even a form of witchcraft. It was only after the medieval period that healing became definitively dissociated from religious vocations, thereby sidestepping this theological issue.

Sámi tradition regarded disease as either the result of interpersonal conflicts or a type of spirit possession. These two overlapped in that disease could sometimes be sent by a person who bore ill will toward another. Sámi took precautions to avoid contact with sick persons, lest the spirit pass into them as well. The Sámi notion comes much closer to modern notions of quarantine and infection than anything current in Mediterranean cultures. The Plague in particular was associated with the demon god Ruto, who was to be avoided at all costs. Peter Sköld's article "Saami and Smallpox in Eighteenth-Century Sweden: Cultural Prevention of Epidemic Disease" (in Northern Peoples, Southern States: Maintaining Ethnicities in the Circumpolar World; Umeå: CERUM, 1996; 93-111) is an excellent source for further information of these cultural norms within Sámi healing. In Boccaccio's account, cited above, we can see that Italians eventually came to share the notion of quarantine, at least in the extreme context of the Plague.

Some final small notes: Dacia is indeed what the Dominican Order called their Scandinavian province. It derives from the Latin name for Denmark. In Northern Sámi, daza means a non-Sámi, usually a Norwegian. For much of the medieval period, Denmark and Norway were united, so that all Scandinavians were called by the term. Gaskalas is a very nutrious plant that Sámi traditionally ate in the early spring. It is called the stinging nettle in English (Urtica dioica ) and is very painful to touch once it has grown some. But when rinsed in warm water first, it can be touched (and ingested!) without pain.