Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348

a free multimedia novel by

Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison

|

Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348 a free multimedia novel by Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison |

|

|

|

|  |

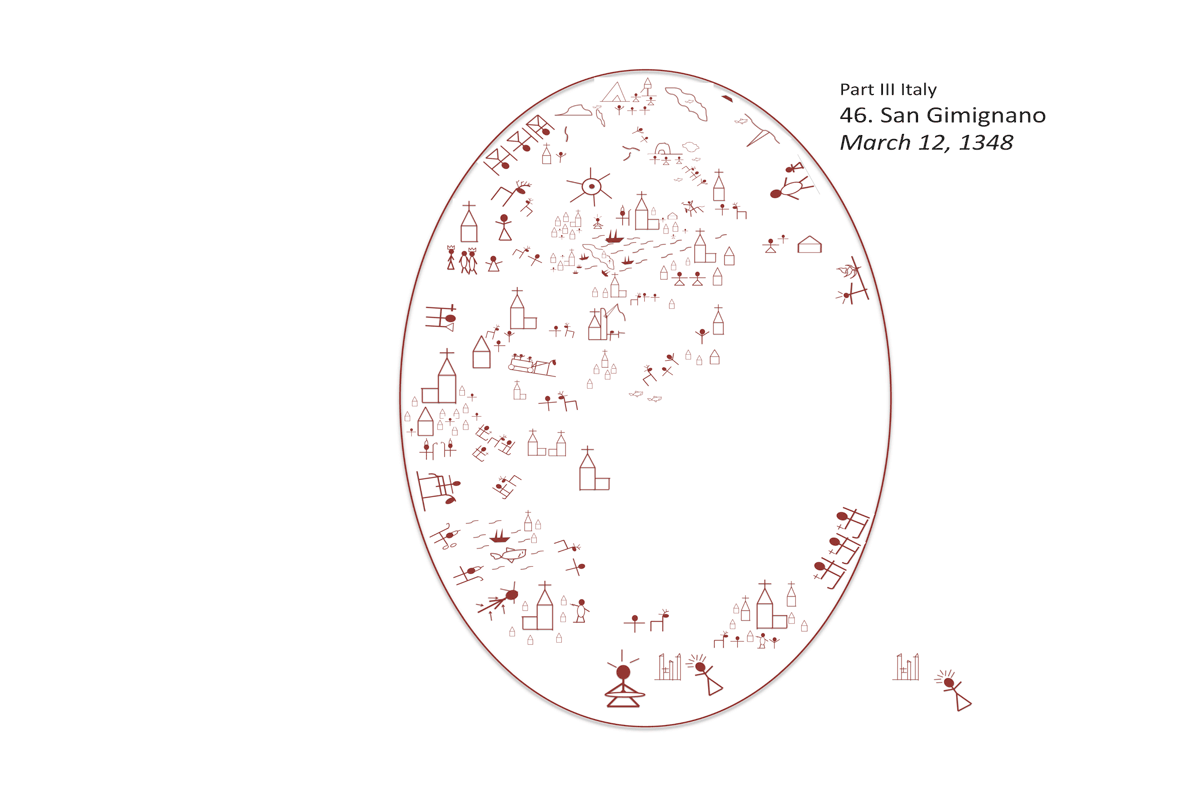

46. San Gimignano (March 12, 1348)

"Go into the village opposite you, and immediately on entering it, you will fid a colt tethered on which no one has ever sat. Untie it and bring it here. If anyone should say to you, 'Why are you doing this?' reply 'The Master has need of it.'"

They could see the towers of the city for miles before they reached it. Perched atop a steep hill that towered over the undulating countryside of vineyards and olive groves, surrounded by a high wall, San Gimignano would seemingly need no internal defenses. Yet its cityscape teamed with towers of nearly impossible height: soaring edifices that proclaimed each family’s status and wealth while also protecting their treasures. The city looked like a plate of jagged teeth, menacing yet somehow grand all the same. No family of any standing was without a tower of its own in this distinctive city, and the fame of its architecture was known throughout the region.

“Ah, there she is,” chortled Buonamico with a kind of pride of ownership he evinced whenever showing something off to his foreign friend, “A city of towers, a city of wonders; one of the several wonders of the world.”

“It is strange to see,” said Bávlos, choosing his words carefully, “Is there a reason they have chosen to live like a flock of crows?”

“A flock of crows?!” cried Buonamico, “Lad, you know not what you say! Those towers are the homes of the finest merchants and noble families in the region: men of spectacular wealth, wives of a girth that makes me look thin, and daughters of every advantage.”

“But why is the city on top of the hill, rather than down in the valley? In the land where I come from, hilltops are for summer pasturing and spring calving, not for building permanent settlements.”

“For defense lad, for defense! Can you not imagine the hordes of brigands and night thieves who would want to pillage poor San Gimignano were he not fortified against them?!”

“Ah,” said Bávlos, “for defense. They are beset with thieves.”

“Aye lad, that they are. This is not the land of the Fenni, Paolino, where your folk are too benumbed of the cold to have discovered the craft of theft! Down here in God’s own country we live amid plentiful demons as well!” Bávlos was still a little irked by Master Simone’s pronouncements on the Fenni from their dinner a couple of weeks earlier, and he cleared his throat after Buonamico’s jest.

“Oh, we have our thieves too,” said Bávlos. “Strangers, night prowlers, sometimes even Sámi themselves that steal out at night to kill others’ reindeer or pilfer their fish.”

“You’re kidding!” laughed Buonamico. “So even folk of that sort have crime! My, what a world is this. However do you guard against them, boy? How do you fortify a reindeer?!”

“Well, it’s funny you ask,” said Bávlos, “because I was just wondering that myself.” He looked at Nieiddash, who was moving more slowly now that she was nearing birth—a month or two and she would be calving. Where could he stash her for the night without the danger of her being stolen?

“My goodness me!” cried Buonamico. “My boy, I’d completely forgotten your little deer. Why, she won’t last the night in that nest of vipers—believe you me! Some band of wayward brigands will be feasting on venison before the night is out!”

“Don’t be so sure, my friend,” said Bávlos. “My grandfather once had a similar problem. I know because my father told me the story and it happened to him. My father was a young man, not yet married and wanting to do some trading to the south, in the place where I was doused.”

“Baptized, boy, the term is baptized.”

“Right. He was setting out for this place and he asked my grandfather if there was any business he wanted him to do down at the trading post. Grandfather had some fine martin pelts that he wanted to trade, but he was getting old and said he couldn’t walk that far. So he gave the pelts to my father and he told him this:‘Go into the trading post and tie up your reindeer and sled with all the trade goods on top right out in the middle of the square. Tie the lead reindeer well but then turn and don’t even look back. Come back for the goods on the following morning.’ So Father did as he was told. He got into the trading post after dark, when all the traders had turned in for the night. He walked into the middle of town, tied his lead reindeer to the post near the well and walked out into the woods a little ways to find a place to spend the night.”

“Disaster, my boy! Your father was a fool!”

“No, listen. The next morning when he got up, he walked into town and there stuck to the reindeer and the sled were three men! No matter how hard they tried, they couldn’t get their hands free! Something held them like iron! My father walked up to them and said, ‘So, you were planning to steal something, eh?’ When he said that, instantly, their hands were free but they had a pain in the ear like someone had whacked them with a log. Their hands were red like the skin had been flayed clean off. They ran away in a flash. Not a single pelt or piece of food was missing from the sled.”

“Do tell, my boy!” said the artist gleefully, “you do tell a story well! How did it happen do you suppose?”

“I don’t suppose anything,” said Bávlos, “I know. Grandfather had put a word on that sled and those reindeer, and nothing could steal them after that. It was like part of Grandfather was there all along, holding those men’s hands until Father returned.”

“Hmn,” said Buonamico. He didn’t believe his friend’s tale in the least. “What a load of nonsense this poor boy’s head is filled with!” he said to himself. Although he didn’t say anything, Bávlos seemed to read his friend’s mind.

“You’ll see, “ said Bávlos. “I’ll put the word on Nieiddash and she will be just fine.”

“You save that deer from the stewpot tonight my boy and I’ll buy you a pint of the finest wine San Gimignano has to offer!” They were on the way up the hill now, and Buonamico and Bávlos climbed off their mules to ease the climb. Bávlos led the three animals behind, while Buonamico, always anxious to put on a good show in front of potential clients, strode in front, gesticulating impressively and greeting everyone he saw as if they were old friends.

“Ah, Giuliano, Ah Mario! Hello good Mrs. Vespucci! My how charming you look today! Yes, I’m in town for just a little while, visiting with some neighbors of yours who may wish to paint their bedroom! Ah yes, all the rage in the greater cities these days, ma’am, all the rage.” As they walked, Bávlos became aware of the stream of humanity that was closing in upon them: people were converging from every direction, aiming at the great city gate that was just ahead.

“Through the widest gate, my lad, as the Good Book says!” said Buonamico.

“I thought it was the ‘narrow gate’” said Bávlos.

“Narrow gate, narrow? Why look at it Paulino: it’s wide enough for two wagons to pass without a delay!”

Bávlos said nothing. “Buonamico, remember your promise. You are going to show me those pictures in the church that will help me learn the faith.”

“Right oh, my boy! We’ll to those pictures straight away! It looks like it may take a while, though!”

Buonamico was right. The gate, wide as it was, was clogged with people now, as guards checked bags and wagon bottoms for contraband weapons and questioned travellers about their business. There were throngs of people beyond the gate, and as Bávlos looked back he could see throngs behind as well.

“Why ever are there so many here?” said Buonamico, scratching his chin. “It’s a prosperous town and a fine hospital, but this seems a bit excessive even so.” But as their turn to pass through the gate drew near, the reason for the crowds became clear: it was March 12.“By our Lady’s belt, my boy! It’s March 12,” cried Buonamico all at once: “the Feast of St. Fina!”

“St. Fina?” said Bávlos, “did you say St. Fina?”

“Yes, my boy, the protectress of the city, a saint whose healing and miracles are known throughout the world!”

As the two friends pushed into the city, Buonamico pulled them into a left street, through a tiny piazza dedicated to the Madonna and back to a little livery stable. The stable was full but the stabler promised to look after the mules and the deer if they tied them up outside. As the stable hand went to fetch some water for the animals, Bávlos touched their necks and murmured something soft. Buonamico watched with an amused smirk. He had little faith that they would ever see the animals again and rather relieved that his neighbor hadn’t been around when he stopped by to borrow them that morning. The friends proceeded up the town, past several hostels. They were able to obtain the guarantee of a bed that night after Buonamico plunked down some of the coins.

“Plenty of money soon, my boy,” he said to Bávlos, “As soon as we deliver my painting to the ‘retreat’ of Bishop Luigi!” After a small bite to eat and a very large flagon of wine for Buonamico, they set out for the cathedral. They found their way completely blocked by other pilgrims, who were lining the streets and watching as a solemn procession made its way uphill toward the church. Lines of boys with city flags and incense led the way, followed by older boys holding banners corresponding to the different guilds, churches, and prominent families of the city. After them walked a long line of clergy, looking regal and holy. And finally, behind them all, came a set of prominent men carrying on their shoulders a litter, upon which sat the carved replica of St. Fina’s head. Carved of wood and leather and guilded with gold, the precious reliquary that housed the skull and brain of the city’s protectress was wondrously crafted to capture the likeness of the holy woman who had died while young, nearly a hundred years before. As the reliquary neared, Bávlos gasped. It was her. Fina. Den fina fruen who had sheltered Nieiddash from the hunters that fateful day and who had spoken so beautifully about being set aside for Iesh. Yet here she was, a world away from that Swedish forest, her sunny blond hair shining as on that day, her eyes wide apart and loving, her mouth tiny and prim. The pink of her cheeks, the soft curve of her neck—yes it was Fina, his Fina, the woman he knew he loved more than as a sister, Fina. How had she come to die, and how had her likeness found its way to this city so far away? Pulling himself together, Bávlos asked his friend who she was.

“St. Fina, you mean? I’ll show you! There are pictures of her story in the church! “ On their way there Buonamico told Bávlos what he knew: of the sweet, charitable, very pretty girl from a family that had largely lost its wealth. Of her long and withering disease that had robbed her of the use of her legs, but also of the patience that she showed throughout. “She was a saint, alive, Paulino, a saint alive! Too holy to sleep in a bed, no: took to sleeping on an oaken table! And she lay motionless on that table for so many years that worms and mice started to make their homes in her posterior, I’m sorry to say.” Bávlos winced at the image. He had seen insects that burrowed into reindeer’s backs to lay eggs deep under the skin, so that their offspring could eat their way out through the poor beast’s hide. It was agonizing for the animals and of course, often weakened the victims to such an extent that they died the following winter. But to have beasts making their homes in one’s own flesh—Bávlos could not have imagined it until Buonamico showed him the pictures there in the church.“Yes, she was a model of patience, that girl,” said Buonamico. “Both parents died and still she lingered on. People used to stop by to try to cheer her up and they found that she had words to cheer them up as well! Sage advice, kind sympathy, and all of that from a girl not a day over fifteen!”

“How did she die?” asked Bávlos. “Well,” said Buonamico, pointing at another painting, “She had advanced notice of the fact, as you see. No less than Pope St. Gregory the Great appeared to her and told her the day that she would die!”

“And she died then?”

“Yes, my boy, she died. But no sooner was she dead than she started to do all sorts of miracles! Her nurse’s withered arm—good as new in no time. Broken pottery—fixed without a seam. Bloody leg wound—healed without a scar. Why that’s why there’s the great hospital here, boy: people are still coming for her cures!”

“And she died how long ago?”

“Close to a hundred years ago!” Bávlos was perplexed. She looked just like Lady Fina from back in Sweden: she even had the same name. But this Fina must have been alive even before Grandfather, or at best, they overlapped in their lives. So how could Bávlos have seen her in the forest that day? Was that a miracle too? It could be, but her hand—he felt as if he could still feel that soft warm hand in his own—no, she was alive. She was also a Fina, but a different one, maybe a twin, like a Sieidi sometimes has. Yes, there must be two holy Finas.

Buonamico did his duty, showing his friend the pictures in the church and explaining their meanings. The entire side wall of the huge church had been divided into panels and painted in the most astounding fashion. Bávlos had never seen anything like it. The figures seemed to leap from their frames. Buonamico was more critical, naturally, but still found much to praise. Along the very top, just beneath the roof, were paintings of Iesh’s early life. One depicted the time when God sent a spirit messenger to tell Maria that she would have his baby. Bávlos could not see the berry that she was given, but perhaps God gave that to her personally once she said it was okay. Then there was the birth of the baby Iesh in a cozy hut with all the animals looking on, breathing the sauna steam to keep things warm. And then the visit from those three kings who had eventually wound up in Milano until they were stolen and sent to Köln where Master Gerhard was still busy building them a cathedral. Then there was a strange picture of men peeling off of the baby Iesh’s foreskin in a custom that Buonamico said was very typical in those days. And then Jooseppi and Maria were shown bringing Iesh to the church in his cradle board so that the aged priest Simeone could have a look too. Then came a wild slaughter of all the babies in the neighborhood when a jealous king caught wind of Iesh’s birth, and Iesh’s escape into a country with much sand along with Maria and the kindly Jooseppi. It was clear that at some level, the artist who had made these pictures knew that Iesh was Sámi: his house and the swaddling were exactly as they would be back home, and the little hut looked more like a Sámi home than a Finnish sauna. Other details had gotten muddled, however, like this business of foreskins. Clearly, these confusions were why Iesh had called Bávlos down to help set things straight.

On the second level of the great wall of paintings, still so far overhead so that Bávlos had to squint to see them in the soft darkness of the church, were stories from Iesh’s adult life. Even as a young man, he had arguments with the elders, who seemed to get things wrong. He had been doused too, by his cousin, San Giovanni, and he had found his chief ally Pekka by a lake, where he was doing some fishing. The boat did look pretty Sámi: it seemed to be made of bent planks and curved upward at the stem and prow. It was very short, too, more of the kind of boat you use when doing net fishing, which indeed, they were. After that, Bávlos saw a wedding feast in which Iesh saved the day by turning water into wine. This was a panel that Buonamico quite enjoyed, bringing on many protestations of thirst that made it look like Bávlos’s lesson would be cut short all too soon. After that came a powerful pair of pictures: Iesh let some of his supernatural powers show through and nearly blinded his favorite followers up on a mountain where no one else could see, and then he called his friend Lazaro back from the dead. He didn’t seem to be using a drum for the ritual, but then, the artist was one of Buonamico’s contemporaries and not necessarily very learned in such matters. Lazaro seemed to be dressed in swaddling clothes for the occasion: maybe the healing involved taking the patient through a kind of second birth. Then came a mighty depiction of Iesh riding a donkey, with hoards of well-wishers putting down their cloaks for the donkey to walk on. The ground must have been swampy, and they wanted to be sure that the donkey didn’t get caught in the mud. Iesh seems to have had a lot of happy followers at that point at least. What had happened?

The bottom register, closest to the eye, were the most painful images of the series. The first showed Iesh having a final dinner with his friends. One of them had fallen asleep on the table, so they must have been eating for some time. There wasn’t much left for them to eat, except for what looked like a roasted otter on a plate in the center of the table. Buonamico said it was supposed to be a lamb, but that the artist had let one of his assistants give it a go. At any rate, it didn’t look like a lamb, and Bávlos made a mental note to ask someone who really knew what Iesh had for dinner the night before he died. Iesh was handing some bread to a nasty looking follower, that one who had sold him for gold. Sure enough, in the very next panel one could see the traitor taking money from the strangers who wanted Iesh dead. Then Iesh was kneeling in some high grass, talking to a spirit messenger while his friends all took a nap. In the next panel the traitor was greeting Iesh with a kiss and a following of soldiers. Iesh looked very displeased. Meanwhile his chief follower, Pekka, was cutting off a man’s ear. The man looked in huge pain and Bávlos could understand why. Then came a panel in which Iesh was being condemned by a crooked judge, someone who wanted to punish Iesh for nothing really at all. The next panel showed poor Iesh tied to a stake, while tormenters whipped his back. Then they stuck briars in his hair. Finally, there was the image of Iesh carrying his risti. There was a rope around his neck and he was being led like a reindeer. One of the soldiers carried spikes that were longer than a man’s foot—nine of them—and a doughty hammer. Everyone looked angry. But Iesh just looked resigned, his eyes turned back at his mother and some other women who were watching from behind. He seemed to be ready for the death they were going to inflict. And then there it was: Iesh nailed to the risti, two others next to him too. His mother had fainted down on the ground and spirit messengers were swooping all around. A man on a dapple grey horse with a very bowed neck was reaching up with an incredibly long spear to see if Iesh was dead. This man, Buonamico explained, was San Longino, who got his sight back when some of Iesh’s blood trickled down the spear into his eyes.

So that was the story. Somehow something had gone terribly wrong between the second tier and the third: the cheering followers had turned tormentors literally overnight, and they had put their best ally to death. What amazed Bávlos still was that Iesh had permitted it: he kept looking at the picture of Iesh carrying the risti, led by the reindeer halter. Why hadn’t he stopped them? Buonamico wasn’t sure either. He said it was because Iesh was a forgiving ally, someone with incredible patience. “Sieiddit never have such patience,” thought Bávlos. He remember how anxious Father became if they delayed at all before bringing Sieidi his fish fat. Waiting till the next day was out of the question: sacrifices had to be prompt, they had to be respectful, and they had to be generous, or Sieidi would take immediate offence. Why was Iesh so patient? Could this be why the strangers kept misunderstanding all his requests? Maybe it was this easy-going approach that led the followers to turn hostile: they wanted to see how far astray they could go and the whole thing had gotten out of hand. It’s hard to keep a herd going in the right direction if you let them go any way they want even for a while. But Iesh seemed to be a different sort of ally. It seemed to Bávlos that he wanted people to act out of love for him rather than out of fear. And to act toward others with love too, and not with fear.

But then why were there these towers in town and why did everyone seem so bent of thieving? Amid this disapproval of the strangers, Bávlos couldn’t help but feel a little guilty about his story about the robbers and Grandfather Sálle as well. Surely Grandfather could have been a little kinder to the men, even while preventing them from stealing all Father’s goods? Bávlos was thoughtful that evening at dinner, despite all Buonamico’s levity and good cheer. Buonamico had delivered his painting to the bishop’s household, and was insistent on drinking heartily the whole night long. A few months ago, it had seemed easy to recognize Iesh as a Sámi and to understand all his ways. Now he still seemed a Sámi, but his motives were not so clear: it seemed like there was really something different that this ally wanted from his friends.

Certainly Fina seemed a loving person: she always had something nice to say to others, and even though she had to suffer all her life with paralysis, she did not mind curing her nurse’s paralyzed arm. Fina had a generosity of spirit that made her different from the ordinary person, Sámi or stranger alike. Yet still, Grandfather Sálle was living with Iesh now, along with a vast number of other kin: clearly Sámi ways met with Iesh’s approval. In some ways, Sámi were much more generous than people around here. Bávlos would have to think some more about all these questions. Perhaps he should ask Santa Fina.

“Fina, are you there?”

“Of course I am, my friend.”

“Fina, was it wrong to put the words on our livestock this afternoon? Grandfather’s magic can prove pretty cruel.”

“It can indeed, Bávlos. Would you like me to watch over your reindeer tonight? I can see if I can help.”

“Oh that would be very kind,” said Bávlos. He could tell that this Fina was as gentle as her twin.

“May I ask also,” he started, “about the other Fina?”

“Yes, Bávlos, you mean den fina fruen.”

“Indeed I do,” said Bávlos. Is she doing well?”

“She is, my friend. And do you know, before too long you will see her again. Iesh is going to be sending her to you!” Bávlos’s heart leapt. Could it be true? Would he see Fina again? The very thought filled him with joy. He thanked the saint and went to sleep.

Night passed well. Bávlos and Buonamico had to share their bed with only one other pilgrim, so there was lots of room for everyone. Sleeping alongside other people again felt good: it had been lonely those months of sleeping alone. Waking to hear the breathing of others was a happy feeling and Bávlos slept contentedly until the morning. In the morning, after breakfast, Buonamico and Bávlos walked back to pick up their animals and continue on their way.

As they crossed the piazza toward the stable they were aware of considerable commotion. People were gathered five deep around the place where the mules and Nieiddash had been tied. “They are amazed to see a reindeer,” thought Bávlos. “At least that means that she has not be stolen.” But when he came nearer he saw that he was only partly right. True, the people were staring at the reindeer, along with the mules. But they were also looking at a man whose hand was somehow fastened to the harness that Nieiddash wore. No matter how he tugged he could not get free. He must have been tugging for hours because he had all but given up in exhaustion and defeat. He stood there sagging bedraggled, wet with sweat and caked with mud and manure, his hand badly swollen in the tangled harness. It was apparent that the mules had kicked and trampled him all night long, and Nieiddash seemed to have gotten in some choice kicks too. His nose was clearly broken: blood had run down his shirt and his face was smeared in a mixture of dirt and blood. There was a sharp gash down his forehead: his eye was swollen shut and he seemed to have lost some teeth. He was moaning slowly in pain. Buonamico looked at Bávlos and said nothing. Bávlos felt ashamed.

At once the crowd seemed to grow aware of the men and silently parted to let them approach. Buonamico’s eyes darted right and left: he seemed to sense that this was not a moment that would enhance his reputation. After a moment, however, he seemed to lift himself into the role of indignant saint, declaring with vehemence:“Ahaa! So, were you, varlet, planning to steal something last night?” As Buonamico yelled, Bávlos drew close to the man, slipped out his own knife and cut through the harness. The man’s hand fell free. He tumbled to the ground for an instant, too stunned to know what to do next. Bávlos spoke:

“St. Fina has guarded our livestock this night and she has protected us, and you, from the sin of theft. Now you must go and pray to St. Fina: thank her for teaching you this lesson and pray that Iesh will forgive your sin!” Instantly the man sprang to his feet and ran away. He did not seem to be heading toward the church, from what Bávlos could tell. In the crowd that surrounded them he could see many crossing themselves vigorously and backing away. St. Fina had performed another miracle that night in honor of her feast.