Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348

a free multimedia novel by

Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison

|

Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348 a free multimedia novel by Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison |

|

|

|

|  |

45. Bruno the Fennus (February 27, 1348)

And the host who invited you both may approach you and say "Give your place to this man," and then you would proceed with embarrassment to take the lowest place.

The drinking and discussion continued long into the night at the home of Master Simone. Buonamico and Giovanni fell into a kind of banter in the way that great hunters or fishermen vied with each other back home in the world Bávlos knew well. There seemed to be little that Buonamico said that Giovanni didn’t quippingly chide, shaking his head and clucking between his teeth. Likewise, Giovanni could scarcely make a statement without Buonamico rolling his eyes or snorting in seeming disbelief. Still, the two seemed to be enjoying their competition and the other people at the dinner—Calandrino, Bávlos, and Master Simone—found the spectacle endlessly amusing. Master Simone’s wife had long since retired to her bed, taking leave of everyone with great cordiality but lingering particularly in her farewell to Giovanni. She seemed to sigh at the very touch of his hand, and Bávlos noticed that Master Simone seemed relieved when she finally left the room.

“Retire to a mountain,” mused Buonamico, returning yet again to the topic of fleeing the Plague. It seemed that somehow he could not quite leave the topic aside, as if the very idea of leaving Firenze—or any other city, for that matter—amounted to an act of profound disloyalty, a mark of cowardice and betrayal. “Out in the wilds reciting poetry, no doubt, “ he grunted. He seemed to pronounce the word poetry with particular disdain.

“Quite so, Master Buonamico, reciting poetry,” said Giovanni with dignity. “And what, pray tell, would be so wrong with that? Folk have enjoyed my poems a great deal, I believe.”

“Oh, there’s nothing wrong with poetry,” said Buonamico innocently, his eyes scanning the ceiling as if watching a flock of low-flying geese, “nothing wrong for idle folk, I suppose.”

“Indeed, I suppose it is chiefly for ‘idle folk’ that I write, friend Buonamico,” said Giovanni with equanimity. “They are the ones who have the time, and taste, for my art.”

“Art?” scoffed Buonamico with a biting tone. “When people want art, it is to painters that they turn!”

“True, true, “ said Giovanni calmly. “Paintings hold great virtues, when well executed.”

“Now there’s a truth!” said Buonamico eagerly. “A fine painting uplifts the viewer and connects him with the holy saint or Our Lady or Our Savior. And that is what folk need in times of crisis, not lines of doggerel about ladies’ pastimes recited in the middle of an olive grove!”

Giovanni bristled somewhat at Buonamico’s remark, but quickly regained his composure. “No, I suppose poems of love and virtue and other great intangibles are of little consequence to some audience members,” he said. “Still, I think many readers—and indeed, many painters as well—have found value in the writings of Master Dante, for instance.”

“Dante!” snorted Buonamico. “Yes, yes, quite a poet that one, I’ll have to admit. Yet tell me, friend Giovanni, for what will Master Scrovegni of Padova be remembered in the passage of time: the inestimable and uplifting paintings that Master Giotto produced for Scrovegni’s chapel, or Master Dante’s mean-spirited depiction of poor old Rainaldo degli Scrovegni as suffering eternal damnation in the seventh level of hell?”

“Indeed,” said Giovanni, “a great artist must sometimes unsettle his audience in order to edify and uplift.”

“Hmph,” said Buonamico. “I suppose I see your point. It is the duty of the artist to lead his audience toward a greater understanding and a better life. Still,” he said, smiling again, “I wonder how one does that by scurrying off to the countryside as soon as a threat like a little sickness rolls into town?”

“The countryside offers great benefits for the thoughtful person,” said Giovanni with a smile. “Is it not so, Master Bruno? Did you not benefit from your days of pilgrimage beneath God’s blue sky? Or did you only benefit from the painted blue of an artist’s sky, wrought with loads of ground-up stones?”

Bávlos responded enthusiastically: “Oh the countryside is a wonderful thing,” he said. “Many times I—”

“The pilgrim’s trek is uplifting because of its destination,” said Buonamico, cutting his assistant off with a loud voice and a wave of the hand. “It is in our arriving at the city, or monastery, or cathedral, and our beholding of the holy relics and fine paintings of the place that our souls truly rise toward God!”

“Is that so?” mused Giovanni. “I have been on pilgrimage myself many a time, and, truth be told, I have found the road the truly uplifting part. Seeing God’s own creation in all its beauty, in all its grandeur—how can such an experience fail to uplift? Is it not so, Master Bruno?” Bávlos nodded eagerly, while Buonamico glowered at him for his disloyalty.

“I should very much like to see this mountain you spoke of earlier,” said Bávlos. “I had no idea that there were any mountains hereabouts!”

“Yes, it is a great mountain, Mt. Morello,” said Giovanni. “And not far from this city: some six Roman miles from the gates, as I recall.”

“So near as that?” blurted Bávlos, his eyes wide. “I had no idea. I would very gladly visit this place.”

“Tell me, Master Bruno,” said Giovanni, clearly pleased with Bávlos’s enthusiasm, especially since it seemed to further irritate Buonamico, “How do folk in your land feel about their cities?”

“Well,” said Bávlos slowly, “in my land we really don’t have any cities at all.”

“No cities?” sputtered Buonamico, wine dribbling down his beard. “Lad, talk sense! How can a land exist without cities? It would be no land at all!”

“My people stay close to the things they need to live on: the forests and waters, fish and game and reindeer. They do not congregate in any great number except in the winter, when folk come together to share their food.”

“Where is this land you speak of?” asked Giovanni with interest. “Is it far from fair Tuscany?”

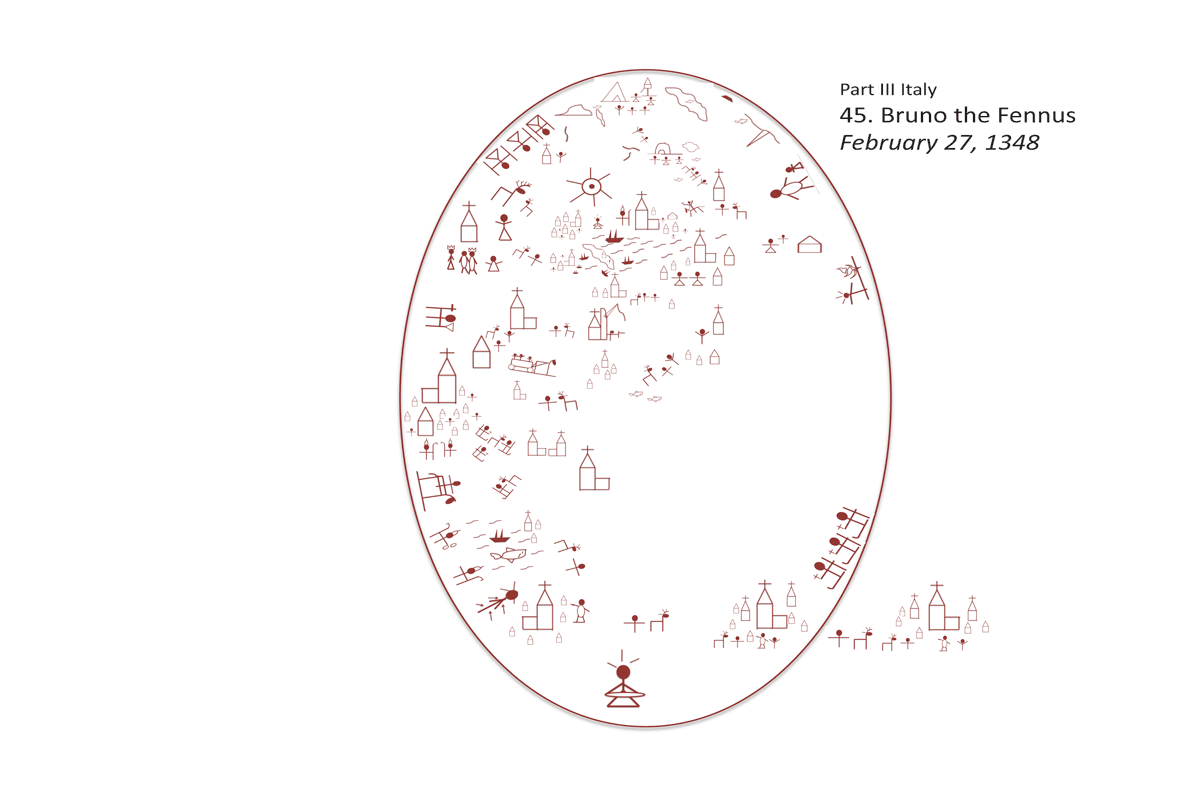

“Very far,” said Bávlos. “I walked for many months before I reached this land. Indeed, but for the fact that I have been drawing a map of the places I’ve seen, I would scarcely be able to keep track of where I’ve been!”

“Ah, there’s a topic,” said Buonamico, rising in his seat and adopting a less combative tone. “Friend Giovanni’s questions remind me of a great mystery we have been grappling with at my workshop. We do not know where this pilgrim and able assistant is from! We thought, Master Simone, that you might help us.”

“Oh, gladly!” said the host, nearly giddy to be included in the conversation. “With my fine library at hand it should be no problem at all to determine where you’re from. Off hand, from your looks I’d say it was from the south of here: Napoli perhaps?”

Buonamico laughed, “No, no, not at all, Master Simone. Our friend here is short, but he is not from Italy. He comes from the north.”

“Well, then, from France!” said the medicus simply. “That was easy.”

“No, not from France,” said Bávlos. “I come from much farther north than France. I sailed south to reach France from the land just south of my own.”

“Far to the north, eh?” said Master Simone, “In the lands where amber comes from?”

“Further north, still, I think,” said Bávlos. He had seen amber in Reval, and he guessed Master Simone was referring to that place.

“Hmmn,” muttered Master Simone, “this is a mystery.” He ushered the company into his library where the books, dozens of them, lay arrayed on tables. Carefully he plied the pages of one manuscript in particular, poring over its writing.

“Tell me,” he said, raising his head for only a moment to glance at Bávlos, “are you ruled by a woman?”

“A woman? No,” said Bávlos. Women were important in certain matters back home, but they couldn’t be called rulers in any way.

“Well,” said the medicus, “to live at the farthest end of the world and yet not have amber or a female ruler. You must be one of either the Peucini, the Veneti, or the Fenni. It says here that the Peucini are like the Germans to the south in their language, mode of life and permanent settlements.”

“Our settlements are not what you would call permanent,” said Bávlos, “We shift them as we need during the year.”

“All right then, not the Peucini,” said Master Simone with finality. “Anyway, the erudite Tacitus who wrote this book says that the Peucini live in filth and sloth, and you seem pretty tidy to me. Plus you traveled all the way to Italy—not a very slothful thing to do!”

“No indeed,” said Buonamico. “Why I have seen this man work with a fever and diligence that would stun many a craftsman in Firenze. In fact, before long he’ll have to join the guild or he’ll out-carve all the sculptors in the city and put them all out of business!”

“The Veneti,” said Master Simone, “Perhaps you are of the Veneti. I wonder if they are related to the Venetians? It says here that they roam about plundering their neighbors. Sounds like the Venetians all right.”

“Well, it doesn’t sound like my people,” said Bávlos. “I think we call those ones the Chudit.” He thought of the marauders who stole from the Sámi and the many tales he had heard of clever Sámi eluding their attacks, stories he had told his friend Jacques not so long ago.

“No, it says ‘Veneti’ here clearly, not ‘Chudit’. Tacitus says so, my boy. They are very fleet of foot and powerful of body.”

“Well anyway,” said Bávlos, “I am not of the Veneti.”

“I would suppose then,” said Master Simone, “that you are of the Fenni.”

Bávlos nodded and thought. Pekka’s people had called him a lappalainen, but the people where Fina lived had referred to him as a finn. “Fenni,” he said, “what are they like?”

“Well,” said Master Simone, rather hesitantly, “It says here—and Master Tacitus is a great authority on such matters—that the Fenni are strangely beastlike and pathetically poor.”

Buonamico burst out in laughter so suddenly that he shot a torrent of wine across his tunic that nearly soiled the book. Master Simone instantly hunched down over the precious manuscript, shielding it from the spray. He scowled. “Careful there, Buonamico! This book is a rarity of great value!”

“I am sorry,” said the painter, “Tell us more, good Master Simone!”

“Yes, well,” said the medicus, now becoming more avid: “Tacitus tells us that the Fenni have neither weapons nor homes, that they eat herbs for food, wear skins for clothing, and make their beds on the ground.” Bávlos had to admit that this sounded somewhat accurate: his people did collect plants for food and yes, the clothes he normally wore were made from reindeer leather and fur, which furnished simply the warmest and most durable clothing one could hope for in such a frigid climate. And yes, the ground was his bed back home: none of these raised beds such as folk used in these warmer climes. It was better to be close to the fire and warm than propped up in the air for wind and bugs to bother, like a piece of fish or meat left on a rack for smoking.

“What else does he say?” Bávlos asked. He wondered how this Master Tacitus had learned such things of his people.

“Let me read you the rest,” said Master Simone: “They trust entirely in their arrows, which they tip with bone since they do not know iron. Men and women alike take part in the food gained by hunting: the women are always present and demand their share.”

“Well, he has gotten some things wrong there,” said Bávlos, “if indeed he is talking about us. For we certainly do know iron well enough, even if we also use antler bone for many things. And women never take part in our hunts: they cannot even touch our weapons! We do share our food with them, but is that unusual?”

Master Simone took no notice of his guest’s remarks as he continued to read: “Of their dwellings, Master Tacitus writes: ‘The little children as well as the old have no shelter from wild beasts and storms but a covering of interlaced boughs, which forms the resting place for young and old alike.’”

“Well yes,” said Bávlos, increasingly defensive, “our dwellings start with interlaced boughs, but then we cover that with skin or with turf to make a very secure and warm home in which to stay.”

Master Simone continued: “Yet they count it as greater happiness to live this way than to groan over farm labor, toil at building, or balance their fortunes between hope and fear. Taking notice of neither men nor gods, they have achieved the most arduous of goals: the perfect happiness of needing nothing at all.”

Again Buonamico guffawed. “Needing nothing at all! Well that fits you to a tee, friend Bávlos!”

“Hardly,” said Bávlos, his eyes flashing now with anger. “No, we don’t farm and we don’t build grand buildings like this one, but we certainly do take notice of men and gods—why, I wouldn’t be here if that were the case!”

“Master Bávlos,” said the medicus, clearing his throat. “I have shared with you the wisdom of one of the much revered Master Tacitus, one of greatest minds of antiquity, a worthy nobleman whose connections and learning, I assure you, are beyond reproach. He has said these things and written them down, and this book, this book, I’ll have you know, is held in the highest repute in Bologna where I received my training. The matter is closed!”

As if to demonstrate his point, the medicus solemnly rose to his full height and closed the book.Bávlos stood silent and fumed, glaring up at his host. Buonamico leaned over to him to pour some more wine.

“Cheer up Master Fennus, cheer up! It could be worse!”

“How so?” asked Bávlos.

“Yes!” said Master Simone excitedly, recovering his good humor immediately: “at least you are not of the Hellusii or Oxiones! It says in Tacitus that they have faces and expressions of men but the bodies of wild beasts!”

“There you go,” said Buonamico soothingly, “See? At least you’re not one of them!”

“I don’t think I need Master Tacitus to tell me who I am,” said Bávlos at length. “I know my father and my family and my people’s ways, and I don’t need any Latin scholar to tell me otherwise!”

“No, I don’t expect you do,” quipped Buonamico, “After all, you Fenni don’t need anything at all.”