Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348

a free multimedia novel by

Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison

|

Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348 a free multimedia novel by Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison |

|

|

|

|

|

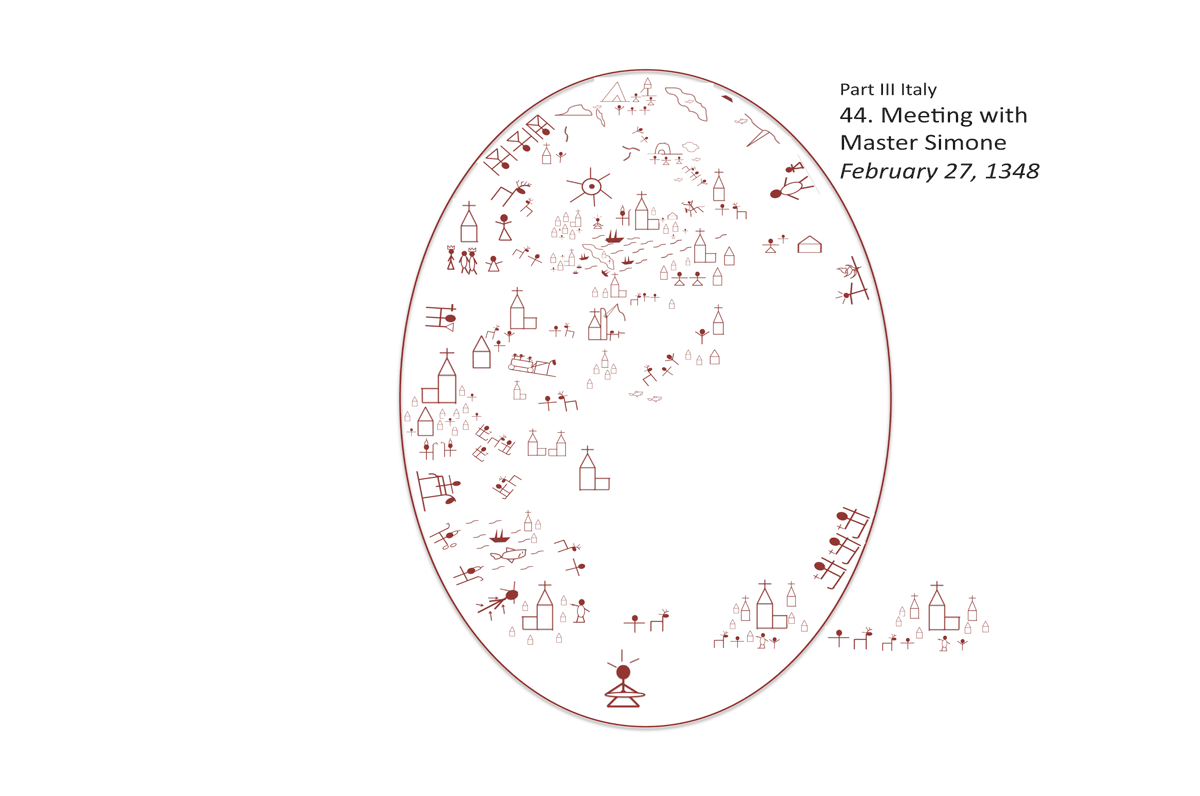

44. Dinner at Master Simone's (February 27, 1348)

When you are invited by someone to a wedding banquet, do not recline at table in the place of honor. A more distinguished guest than you may have been invited...

It did not take long for Buonamico and Bávlos to reach Firenze, where the artist had a small workshop every bit as cluttered and dusty as the one they had left behind in Pisa. This place was different, however, because it was the city where Buonamico had grown up: a grand, powerful place with throngs of people and gigantic buildings. Buonamico seemed entirely in his element in this city: people knew him and waved as he walked down the street, and Buonamico resumed a very busy social life that revolved around leisurely late afternoon dinners and long nights of drinking and talk.

Nearly two months had passed when Buonamico at last mentioned that it was time to visit the man with the great library. “No dinner for us tonight, signora,” announced Buonamico with his characteristic flair, “Bávlos and I are dining out!”

“Is that so, signore?” said the old woman with a grunt. Buonamico’s housekeeper here in Firenze was a good deal less garrulous than her counterpart in Pisa, but then she had known Buonamico longer. This city, after all, was the site of Buonamico’s main workshop, and he paid for this woman’s work whether he was at home or not.

“Well, I’ll make dinner for Angelo and myself then.”

“Do so, good lady, do so,” said Buonamico with a jovial nod of his head. “If this dinner goes well tonight, there’ll be plenty of money for any sort of dinner for some months to come.”

“Ah,” said the woman, “So you’re fishing for a commission!” She had suddenly become more animated.

“Yes, signora,” said Buonamico with a solemn nod, “that is precisely what I am doing. Master Simone has invited me to dinner—”

“Master Simone?” snorted the woman. “That old windbag? You’ll get no decent commission from him! He doesn’t know art from a plate of turnips!”

“Yes, well, “ said Buonamico, amused by his housekeeper’s outburst, “you are certainly right on that count. A learned medicus, that one, but one of the most excellently ignorant and foolish men you will ever meet!” he laughed. “It’s just lucky he was born rich, because his patients never live long enough to pay him. At any rate, he is well connected in certain social circles, signora. And he has invited to dinner Master Boccaccio, a man associated—albeit rather informally I must admit—with one of the most prominent families of our city, I’ll have you know.”

“Ah, Boccaccio the poet!” said the woman with a nod. “Now there’s a distinguished man!”

“Yes, quite,” said Buonamico. “And Bávlos and I shall dine with him tonight!”

“I sir?” said Bávlos. “Are you certain you want to bring me along?” He felt uncomfortable in formal dinners. In France, they had been tolerable because Girard and the other clerics were always so careful to make him feel at ease. But it was not the Sámi way to eat at the same time as others, let alone do so with lots of dinner talk and witty remarks. And the meals were so interminably long here, with so much food and wine and clutter. The longer the meal dragged on the faster and louder the talk became, and the wine had a knack for stealing Bávlos’s ability to understand what he heard. He would much prefer to remain at home with Angelo and enjoy a simple bowl of soup.

“I need you there!” said Buonamico, slapping him on the back. “You have to sing my praises, you see!”

“Sing your praises?” said Bávlos. He had not known Buonamico to have much trouble doing this work for himself.

“Yes, you see I can’t really go on too much about my work myself—that would be unseemly. I need you there to drop in some comments about how pleased my patrons always are, how prompt I am with my work, how diligent, how masterful—you know, the usual stuff. Calandrino of Calendrano will be there too, and he’ll be fishing for the same catch, to borrow a metaphor from your world,” said Buonamico. “Not that Calandrino’s work is any real competition for mine—not in the same class at all, really, but who knows what this poet knows or has heard about us from Master Simone? Perhaps Master Simone has already talked up Calandrino’s dubious talents. Master Simone still bears me some ill will, I think, from a little prank I pulled on him some time back. So, at any rate, we’ve got to convince Boccaccio that we’re the right artists for his job!”

“So I am to repeat compliments made of your work?” asked Bávlos. “Yes, lad, that’s the idea—just repeat some of the glowing praise that the Abbess Ursula gave my San Sebastiano in Pisa—that should do the trick. Just slip it into the conversation and I will act flustered and embarrassed, but you go right ahead and keep praising me just the same. And before you know it, this Boccaccio will be asking us to do him a painting as soon as possible.”

“Well,” said Bávlos. “I think I understand. I will try to remember the abbess’s list of good points she had regarding your painting. I think she said that there were three, but I don’t exactly recall—”

“That’s the ticket!” shouted Buonamico merrily, “and anyway, while we’re there we can ask Master Simone if he can figure out where you come from! He’s the man with the great library that I told you about. Full of all the book learning from the university at Bologna. His mind is filled with Bologna learning, that one, and all that should make it possible for him to at least guess where you’re from!”

“Wonderful!” said Bávlos happily. It would be nice to know where he was from. Of course, he reflected, he already did know all about the place he came from —its every river, lake and glen. But it would be nice to have some name he could attach to the place for Italians to hear, so that they would nod in comprehension instead of staring at him in confusion whenever he tried to explain the place from which he came.

At lunch time, Buonamico’s companion Calandrino arrived and the three men walked to the old marketplace, where Master Simone had his store and home. Calandrino was a thin and bent man, with a very large head and a kind of worn-out expression. He seemed quite the opposite of the robust and corpulent Buonamico, yet the latter seemed to enjoy his company greatly. For his own part, Bávlos always loved the bustle and sights of the market: wagons full of produce and livestock, tables laden with goods for sale: the Old Market was the very hub of the city. They passed the little church of Santa Maria in Campidoglio, hardly bigger than a craftsman’s shop on the outside, but one of the oldest churches in the city. They stepped inside to admire the altarpiece: a grand Madonna painted by Master Giotto, that artist that Buonamico always spoke so reverently about. Light from the clear day shone through the little church’s single high window upon the altarpiece at the other end of the church and behind the altar.

“There was none like old Master Giotto for making beautiful paintings!” said Buonamico, gazing with some envy at the painting. “Look at her face, and the love she shows the Babe.” It was true. Although rigid and formal, this Notre Dame had also a tenderness that made Bávlos think of his own mother, a kindness that reached out beyond the picture. The smiling child, too, seemed to look into his very eyes, with encouragement and joy. The painting had everything that Master Claes had put into his Madonnas in Hattula and Reval, but there was something more as well: a kind of naturalness that was both shocking and delightful. How was it that a flat surface could so evoke the contours and softness of a mother’s flesh? How could an artist so control an image that his viewers felt they were face to face with a living person? Clearly there was something remarkable about the art of these Italians, something Bávlos had scarcely imagined was possible before.

“That Giotto had the plainest children you’d ever want to see,” said Buonamico musing. He always enjoyed telling Bávlos details of the personal lives of great painters. It somehow made the wonder of their workmanship that much more remarkable. “A cleric once asked Giotto how someone who made such beautiful paintings could wind up with such homely children.”

“What did he say?” asked Bávlos.

“He looked at the cleric and said, ‘Well, father, I made those in the dark.’” The men laughed. Then crossing themselves reverently, they stepped back out into the bustle of the day.

“How wondrous it is to see so ancient a church,” said Bávlos, “that comes from the very beginnings of the faith in this land.”

“Mark my words,” said Buonamico impressively, “that church will be standing till the end of time! Little though it is, it’s one of the sincerest houses of worship in all Christendom.”

Bávlos reflected on Buonamico’s words. For these Italians the greatest value was always attached to immobility: nothing that was great ever changed, and no one of status ever moved. How different their ways were from his own: for his people, the greatest beauty lay in the fleeting, the momentary, the frail. The cool light of a spring morning, the sound of a bird on a high hill: these were the greatest tributes to the heavens. And people too were mobile: to stay in one place was to fester and rot. No, it was better to keep circulating, moving across one’s family’s lands in a way that partook of the land’s riches as they came in season, not plunking down in one spot until “the end of days.” It seemed to Bávlos that Iesh had valued the Sámi way: why else did he spend his days wandering from place to place during his ministry rather than setting up shop in a single town?

At length they came to a door with a sign above it in the shape of a pumpkin. “He deals in plants and pigments, too,” said Buonamico. “That’s how I came to know him.” The men entered the shop. A thin man dressed in a scarlet robe was sitting at a table, his head tilted back. He was snoring. “Master Simone,” called Buonamico, knocking on the table, “Master Simone! We have come to dine!”

“To dine?” asked the man as he sprang from his seat. Bávlos could see that the medicus was a tall man, with long black hair and prodigious sideburns. He looked at the men with a self-important air and asked, “You have come to dine?”

“Why yes, man!” cried Buonamico. “You invited us just last week!”

“Oh did I?” said the man confusedly. “I, well,” he said hesitantly, “that is to say, I certainly remember inviting someone today—” His voice trailed off as if to hide some treasured fact.

“Yes, yes,” blustered Buonamico. “You invited Master Boccaccio the poet as well! Don’t you remember?”

“Yes,” said the man with a look of further confusion. “I certainly remember that.” After a moment’s pause he sighed softly and announced: “I must tell the cook of your arrival at once!” He hurried out a door that led from the store into his household. As the door closed behind him, Buonamico nodded his head wryly and winked at Bávlos.

Calandrino noticed the nod.“We were not invited today, were we?” said Candrino drily.

“Not technically,” said Buonamico, “if by ‘invited’ you mean being issued a specific written notification that one is welcome to come on such-and-such a day to eat at such-and-such a time…”

“That is the usual meaning of ‘invitation,’” said Calandrino.

“Friend,” said Buonamico. “Men of status must be prepared to entertain worthy artists whenever they materialize. And besides, this is to be a dinner with the great Boccaccio. Surely you can see the utility of our attending?”

“I suppose,” said Calandrino with resignation.

Despite these ambiguities of invitations issued and received, the dinner began cordially and on time, thanks to the able offices of Master Simone’s cook and housekeeper. Boccaccio arrived in due order and pleasantly greeted all the other guests. He was a tall man, with a wide face and a prominent, hooked nose. He seemed very elegant, much like the fine aristocratic clerics Bávlos had come to know in France. Master Simone’s wife seemed particularly enchanted by him: she nearly fainted when they first met, and she spent most of the dinner staring at him with awestruck eyes. Calandrino had mentioned to Bávlos that Boccaccio made his living writing poems that delighted women, and Bávlos suspected that the wife’s stares were a product of this career. Before long, he was on first name basis with all of the men, and they in turn called him Giovanni. He seemed to have trouble with Bávlos’s name, however, and repeatedly called him Bruno. Bávlos corrected him several times, but the more Giovanni called him Bruno, the harder it was to break him of the habit. And eventually, Bávlos simply gave up and accepted the new appellation as a temporary nickname.

The dinner itself was very amusing. Master Simone flitted about nervously, ordering the servants, talking nonstop about small details of the food, and looking at Giovanni with a doting smile. Giovanni kept mostly quiet, answering questions when directly asked, but preferring, it seemed, to let others do the talking. Buonamico, anxious to make a good impression on this potential patron, told a series of funny tales about his various adventures, most of which seemed to center on playing mean tricks on his friend Calandrino. He had once convinced Calandrino that there existed a type of stone that made one invisible. Then he pretended not to see Calandrino when he picked up a particular rock so that the poor man had become convinced that he had discovered a specimen of this wondrous stone. Calandrino was displeased at being reminded of the prank, which had apparently led him into some heated arguments with his wife, although Bávlos did not quite understand how. And then Buonamico told how he and Master Simone together had convinced Calandrino another time that he was pregnant, and how Calandrino had been filled with panic trying to imagine how he could ever give birth to the child inside him. Everyone laughed heartily at these tales, apart from Calandrino, who looked sullen and embarrassed. But that only added to the merriment as far as the rest of the party was concerned, and people laughed riotously as they drank down goblet after goblet of rich Tuscan wine.

At length, Buonamico turned the conversation toward painting and then, after some rather clumsy conversational maneuvering, gave Bávlos an opening to recount the Abbess’s words of praise for his most recent painting: “I’m so stuffed with food that I could nearly pop!” he said. “Why, even looking at a painting of San Sebastiano with all his arrows would likely cause my gut to burst!”

“Speaking of San Sebastiano,” said Bávlos dutifully, “ Did you know, Master Giovanni, that my master just completed a painting of the same for the abbess of the great convent in Pisa?

“The Abbess Ursula?” asked Master Simone with interest.

“Yes, that’s the one,” said Bávlos. “She—”

“Alas, poor woman,” said Master Simone, shaking his head solemnly. “It was sad how it happened.”

“How what happened?” asked Buonamico, somewhat disgruntled that his ploy to repeat her words of praise was not working as planned.

“Why she died!” said Master Simone. “Didn’t you hear? She, along with most of the convent all succumbed to the Plague the very day after the Feast of the Epiphany!”

“Died?” repeated Bávlos in surprise. “But how?” He recalled the abbess’s words regarding her sick nuns that evening and in his mind he pictured a dark rider galloping toward the convent with sword held high—Ruto on a rampage.

“The Plague,” said Master Simone with a sigh. “Swallowed up loads of people in a matter of days. Pisa is a shambles.”

“The Plague?” asked Bávlos.“What is this Plague like?”

“A terrible thing,” said Giovanni, suddenly quite animated. “It begins simply enough: a lump in the groin or in the armpit. A hard, knobby lump, sometimes as big as an apple. And then somehow, the disease begins to spread through the rest of the victim’s body, causing terrible bleeding sores to emerge in various places or sometimes causing one’s spit to turn black. No treatments seem to help and few are the folk who contract this disease who are not dead within three days. In fact, even pigs and cattle can catch the disease from looking or talking to a person who is ill.”

Bávlos shuddered. Ruto was a cruel foe.

“People say it was the work of the Jews,” said Calandrino ominously. “They pour poisons into folks’ wells so that all the Christians will die!”

“Rubbish!” snorted Buonamico. “Why would they want to kill all their clients that way? Everyone has use for a Jewish money changer, especially these days.”

“No, it wasn’t the Jews,” said Bávlos quietly. “It was soil from—”

Suddenly Bávlos felt a sharp kick in the shins. Buonamico was glaring at him, his eyes wide and wild. Bávlos closed his mouth and glared back. For some reason, Buonamico never liked to hear about Bávlos’s views of the soil at the Camposanto.

“Soil?” said Giovanni, with a look of interest.

“Don’t mind my apprentice,” said Buonamico with a wave of his hand. “A foreigner, you know. Still, it’s a great pity that the abbess died there in Pisa. She was a true connoisseur of the arts!”

“You did a San Sebastiano for her?” asked Giovanni, returning to a more pleasant subject. “Yes, and she was most pleased with it, if I do say so myself,” said Buonamico eagerly. “Most pleased indeed! I don’t quite recall her words, do you Master Bávlos?”

Giovanni did not allow Bávlos to answer. “When was it that you saw her last?” he asked.

“Why, we were there—” started Buonamico, somewhat surprised by the question.

“On the Feast of the Epiphany,” said Bávlos.

“Or perhaps a day or two before then,” said Buonamico hurriedly. To Bávlos he seemed uncomfortable about having to admit that he had been to see the abbess on the very night before she died.

“And then you left before the Plague arrived?” Giovanni asked. “That was a lucky move!”

“Yes, well,” said Buonamico, avoiding Bávlos’s eyes, “I received a new commission from Bishop Luigi there—an Annunciation of very large dimensions—and I decided that I needed the space of my home workshop here in Firenze to do the job right.”

“Ah,” said Giovanni, nodding. “A lucky commission that, I should say, and in more ways than one!”

“Master Giovanni,” said Master Simone, returning to the question of the Plague. “You stated a moment ago that they have found no cures for this Plague. In that, I must tell you, you are quite wrong, I’m sure. We have medicines in this city that can take care of virtually any disease. I grind them up myself in my shop right in the next room, and I assure you that, with all the training I received at Bologna, they are likely to be of great effectiveness against any such affliction. I should not doubt that we medici could put the Plague to the rout if it dared come to the gates of Firenze!”

“Besides,” said Buonamico, trying to put all at ease, “ The city council has taken great precautions to keep the Plague away. No sick folk are being let through the city gates, and the holy friars of Santa Maria Novella are taking pains to purify the air in various places. And, of course, the parish priests are busy planning various processions of all the most potent relics to appeal for help from the holy saints. So with all these precautions, I cannot imagine the Plague posing us any problems at all. And after all, such pestilences hit coastal ports and the like, not inland cities like Firenze!”

It seemed to Bávlos that his friend had been doing a good deal of thinking about this Plague of late, even though he had said nothing of it to Bávlos before now.

“Yes, quite right,” said Giovanni. “It’s quite unlikely the Plague will venture this direction.”

“Among my people,” said Bávlos quietly, almost as if to himself, “it is the custom to flee from disease. You leave the sick with the things they need to take care of themselves and then you hightail it out to the forests or hills and wait until the sickness has passed.” Again he imagined a charging Ruto, galloping across the countryside on his black horse.

“You mean to say,” said Master Simone in a tone of astonishment, “that you do not stay to nurse the ill?”

“No,” said Bávlos, simply. “Not usually.”

“But you wouldn’t do such a thing if I came down with an ailment, would you?” asked Buonamico, leaning back in his chair. Buonamico had been drinking steadily all evening and Bávlos could not quite tell if he was asking in jest or in earnest. “You wouldn’t leave me all alone to battle my illness all by myself?”

“What would you have me do?” asked Bávlos, hesitantly. “Why stay with me, lad, of course!” said Buonamico. “Run fetch some wholesome wine to quench my thirst or some medicines of the sort Master Simone has been describing! Then I could recover!”

“That is not the way it is done in my land,” said Bávlos, looking down at his hands. He suddenly felt ashamed.

“But it is the right thing to do,” said Buonamico with vehemence. “Surely you see that, lad?” Bávlos felt a pang of guilt. Buonamico was right. Bávlos was no longer an ordinary Sámi, after all: he had been called to be a noaidi. And noaiddit often were called upon to heal. Hadn’t Grandfather Sálle himself lost his life fighting to heal Elle only two winters ago? She had been close to death and all had fled her side but for Grandfather. He had stayed by her side and bargained with the spirit that was afflicting her, offering his own life in exchange for hers. Naturally, the spirit leaped at the offer: Elle soon recovered, but Grandfather died only two weeks later. Bávlos could still hear Mother’s words from the morning after her dream of the stranger: “We’re not losing our Elle to some stranger. Not after everything we’ve gone through to keep her safe up to now!” Bávlos decided that he would just have to learn more about healing as quickly as possible. If Ruto was going to attack in these parts too, he had to be ready.

“I guess you are right,” he said aloud.

“Now there’s a good lad and a good friend!” laughed Buonamico. Bávlos couldn’t quite tell if all the preceding had been serious or not: perhaps Buonamico had just been playing one of his pranks.

“Still,” said Giovanni rejoining the conversation, “your Bruno here has a point. Why not take to the hills when the Plague comes round? Why, I have kinsmen up near Mt. Morello. What would be the harm of heading up there if the Plague ever reaches Firenze? Just me and a few servants and perhaps some good friends for company. We could sit around and tell stories just like we’ve done tonight! What a grand time that would be, don’t you think?”

Everyone nodded and chuckled jovially, wishing to put the whole idea of the Plague and its potential far out of mind.