Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348

a free multimedia novel by

Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison

|

Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348 a free multimedia novel by Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison |

|

|

|

|  |

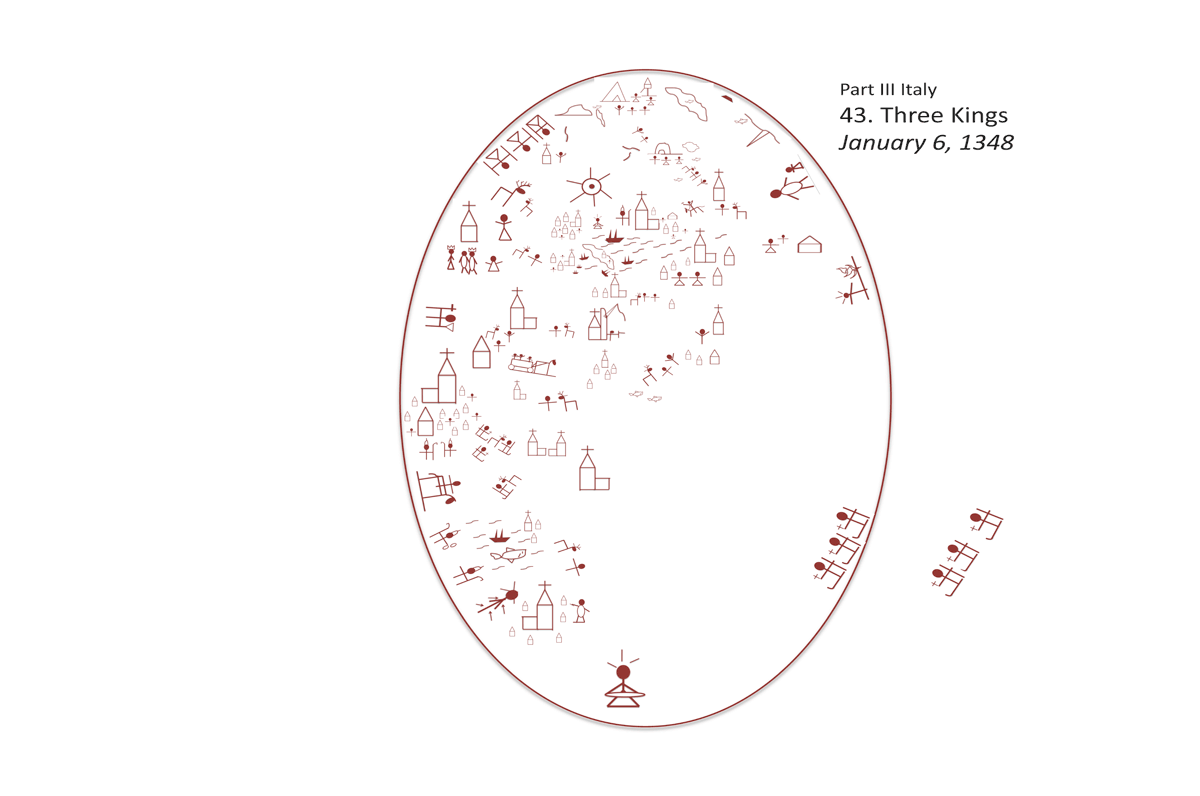

43. Three Kings (January 6, 1348)

When Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judea, in the days of King Herod, behold magi from the east arrived in Jerusalem saying, “Where is the new-born King of the Jews? We saw his star at its rising and have come to do him homage.”

“Big day today,” said Buonamico brightly, “Both a Sunday and a feast!”

“Is it?” asked Bávlos, yawning, as he climbed out of bed. “A good day for one’s last in this city.”

“Indeed,” said Buonamico rather testily, “if one has to leave.”

“We do,” said Bávlos gravely, “It cannot be avoided.” Bávlos accompanied his friend to the people’s mass at the great cathedral. The laity’s portion of the great church was thronged with the faithful: they were packed in so tightly that one could scarcely turn around, and the air was heavy with the smell of wet wool and sweat. Bávlos was sure that impressive numbers of clerics were busy behind the great partition as well, but he had little way of knowing. People were coughing nearly incessantly and it was hard to hear anything at all of the mass.

“Don’t you love a great crowd?” said Buonamico loudly, as he looked about him, beaming.

“I think I like the smaller churches,” said Bávlos with candor. He felt overwhelmed by the crowd and the noise and the smells. “I like the small chapels where you can see the altar and even hear the readings and prayers.”

“Such things are for the clergy, lad,” said Buonamico shrugging. “We’ve got art, and that’s all we need. It’s men like us—the artists, the painters, the sculptors—that give the faithful their schooling in the faith!” Buonamico’s high sense of duty and accomplishment was in true form this morning. Bávlos contended himself with repeating his Aves and Paters for the duration of the mass, and dutifully waited in the long line to kiss the pax and the even longer line at the end of the service to receive the blessed rolls that took the place of the Eucharist. By the end of the ceremony he still had no idea what feast day it was, and so, he asked Buonamico to explain.

“Tell me then, Master artist, what day have we just celebrated?”

“Why, it’s the Feast of the Three Kings, man!” laughed Buonamico, “Didn’t you know?”

“The Three Kings?” said Bávlos, “Who are they?” He knew of the one “king,” another name by which they referred to Iesh, and of the various kings of the lands he had traveled through, but he had no idea who the “three” kings were.

“Why they were great kings of old who came to visit the Christ child when he was born. They followed a star to the stable. You know, painters love to do Adorations: lots of glitter, lots of rich fabrics to depict. You can add little slaves and footmen, and caravans too, if you want. Camels! Horses with fine saddles! Exotic birds! You name it! It’s got to be a feast for the eyes, and the wealthy patrons always appreciate it when you make the kings look like them!” Buonamico’s explanation was typical of the way he tended to approach his faith as far as Bávlos could tell: all matters of religion ultimately came down to the techniques one would use to depict them on a wall.

“Where were they from, these kings?” asked Bávlos. In any case, it was comforting to hear of other travelers who had journeyed far to worship or serve Iesh.

“I don’t think they were from off your way, if that’s what you’re thinking,” chuckled Buonamico. “Their relics used to be kept at the cathedral of Milano until about a century ago, but then they were confiscated by that wretched Federico Barbarossa and given to some church in Germany.”

“Köln?” asked Bávlos.

“That’s what they call it there, I believe,” said Buonamico. “Have you been there?”

“Briefly,” said Bávlos. Hoping to avoid any further discussion of Köln, he quickly asked: “So these three kings: they were from Milano?”

“No, not from Milano,” said Buonamico, “or at least, they weren’t all from there. I know for a fact that their names were Melchiorre, Baldassarre and Gaspare, and that that they came from three different parts of the world: from Asia, Europe, and Africa. I suppose the European one could have been from Milano. They brought three different kinds of treasures with them, too: gold, frankincense, and myrrh. Truly kingly gifts, and a great detail for one’s painting” he said. “You want to make the packages look different enough from each other that the viewer can guess which is which, but you also have to make the gifts look more-or-less the same. It wouldn’t do to have one king being wildly lavish and the other two getting by on the cheap!”

“Do you know anything more about these men?” asked Bávlos.

“No lad, that has always been enough for me,” said Buonamico with a touch of exasperation in his voice. “If you want to know more than that, you can ask the Abbess Ursula later. She’ll likely know lots more. We need to stop there tonight to pay our respects before heading for Firenze. I think she is very pleased with the San Sebastiano, but it never hurts to let clients gush a little about how delighted they are with your work. Then they’re more likely to hire you again for another job.”

“So we are going to leave tomorrow?” said Bávlos anxiously.

“Yes, lad. My work here is done, and I should get back to Firenze to start work on the new piece for Bishop Luigi. I would stay here, but—”

“No!” snapped Bávlos, “We must go!”

“That’s what I was going to say,” said Buonamico dryly. “I would stay here but for my eccentric assistant who insists that the soil of the Camposanto is angry. You know,” he said with some irritation,“it’s usually the master who decides where a painter is going to go, not the apprentice!”

Bávlos said nothing. He knew that from Buonamico’s point of view his worries about the soil made little sense. But these Italians knew so little about the supernatural world. And there were so many ways one could offend spirits or powers. Bávlos looked at an old woman who was hobbling along in front of them. She was limping and groaning, holding her hand to her stomach. Buonamico noticed her as well.

“Something wrong, grandmother?” said Buonamico politely. “Can I help you to your door?”

“Please,” said the old woman. “I must have strained myself cleaning yesterday. I just need to lie down.” She coughed a little and hobbled toward the small doorway of a house nearby. Buonamico supported her arm to the doorstep and then bowed with an elaborate flourish of his hat. The woman seemed grateful for the help, but barely acknowledged it, as she hobbled coughing and shaking into her doorway.

Buonamico and Bávlos returned to their lodgings, where Bávlos and Angelo set about packing up the myriad pigments, brushes, tools and tunics that made up Buonamico’s stock in trade. It was evening when the men were finally ready to call on the Abbess Ursula. Buonamico, Bávlos, and Angelo had shared a soup made out of dried bread and vegetables for their evening meal. The landlady had taken ill, but she had left the pot for them to help themselves. After eating, Buonamico and Bávlos walked toward the convent beside the church where they had first met. It was the first clear night they had had for several days, and Bávlos was glad to see the sky again. The crescent moon gave little light even though it was high in the sky, and Bávlos could make out the star he recognized as Gállá on the eastern horizon, and above that, the rising line of Gállá’s three sons. He had noticed that Gállá and his sons climbed higher into the sky over this land than at home, while their rival, the demon Favtna, seemed less willing to appear at all. Back home at this time of year, Favtna virtually never stopped his prowling: one could always see him ranging along, from the sky over the cold sea where he rose, across the horizon where the sun rose in spring, climbing upward and highest in the direction of these southern lands, before dropping back to the horizon in the direction in which the sun set in spring. In these parts, in contrast, Favtna didn’t rise until late at night, and by the time he had gone from the horizon to the sky above the place of the rising sun, the sun was already rising and he disappeared. All in all, the skies seemed more propitious here.

Perhaps the difference lay in the sun, though, Bávlos reflected, and not in the stars. For the sun, Bávlos had noticed with some resentment, was a good deal more generous here than at home. Rather than becoming scarce for the entirety of the winter months, she seemed content to rise in the morning and grant the people a full day of work before setting in the evening. The nights were much shorter, and Favtna never had the opportunities he enjoyed in the lands of the Sámi. Bávlos thought it strange that the sun would so favor one land over another. After all, was not the sun an ancestor of the Sámi? And was not Gállá also an ancestor? Why did Iesh treat this land so much better? Clearly Iesh must have a reason: he had summoned Bávlos from his own land and family and life to serve these people: they must be somehow favored.

It was also strange that these skies did not seem to know the Guovsahas, the light that can be heard. Why did the streams of color that so marked winter nights back home not appear in this land? Their dramatic performances seemed completely unknown among the Italians. Bávlos had tried to describe them to Buonamico: the shimmering curtains of light that appeared in the sky, waiting for any sound from the viewers below. But Buonamico had said that there were no such things here at all, apart from colorful sunrises and sunsets. The supernatural powers of the Sámi world seemed to be kept at bay here, even when folk did foolish things like stealing graveyard dirt.

“I wonder if Elle is looking at Gállá tonight,” Bávlos said to himself. “I wish I could see her again.” He reflected that such was not likely to happen anytime soon: his land lay months away from where he was now, and in any case, Iesh had not given him any indication that he would be allowed to return home. He was here to serve these favored ones, the ignorant and self-important citizens of the city called Stop. Bávlos could feel his resentment rising though he tried to hold it back.

When Bávlos and Buonamico arrived at the convent, they found that Abbess Ursula had been expecting them. “Welcome, Master Buonamico,” said the old woman as she ushered them through the convent gate and into a small room nearby. She was short and plump, with a dark complexion that looked as if someone had rubbed reindeer butter into it for many years. Her cheeks were round and full and her nose gracefully hooked. Her habit was of a plain black fabric and she wore no insignia that would identify her as anything but a simple nun. “I am so glad that you came to say goodbye,” she said. “Things are in a bit of a shambles here this evening: many of the sisters have taken ill.”

“I’m sorry to hear that,” said Buonamico. Bávlos looked at him with alarm: there certainly seemed to be many people taking ill in town today. Buonamico refused to return his knowing glance and instead politely directed the abbess’s attention to the topic of his painting. She responded by enunciating with great vigor her praises for his work.

“Your painting is of great value, Master Buonamico,” she said, clapping her hands together. “For it possesses three chief virtues: first, there is the skill of the figures: each person looks clearly and recognizably as he should, with all his limbs and eyes and hair. Second, there is the skill of the colors: for each hue in the painting is as true as one could imagine: the blue of the sky, the gold of the holy saint’s flowing hair, the red of his running blood. All rendered with marvelous skill. Third, there is the skill of the emotions: one can see the holy saint’s pious resignation, the executioners’ frustrated anger, the foreman’s embarrassment and confusion. It is a work for the ages, Master Buonamico, a work for the ages!”

The conversation came to a lull after what seemed quite a long encomium to the skills of Buonamico, with many interjections by the artist regarding his intentions and achievements. Bávlos used the pause to try to steer the discussion back to the topic of the nuns’ illness. “You say that the other sisters have taken ill?, Abbess Ursula?” he asked. Buonamico frowned at the question. He was clearly bothered at having his praises cut short in this way, and for such a disagreeable topic.

“Well yes, they have,” said the abbess with a note of concern in her voice. “This time of year such illnesses spread so easily. I’m hoping that a little rest and prayer will take care of it, though.” Bávlos nodded and a silence ensued.

“Dear Abbess,” said Buonamico, breaking the silence and changing the subject, “My friend here is a pilgrim from the north. He knows precious little about the Three Kings, and I thought you might be able to enlighten him.”

“Gladly!” said the abbess, her eyes brightening at the topic. “There is such a wealth of misinformation of them, you know!”

“Misinformation?” said Bávlos, glancing at Buonamico, “What do you mean?”

“Well, like the very notion that they were merely kings,” said the Abbess. Buonamico cleared his throat and began to look out a window.

“They weren’t kings?” asked Bávlos.

“Not at all,” said the abbess. “Or actually they were kings, but more importantly, they were magi!” She said the last word with great emphasis and excitement.

“Magi?” asked Bávlos.

“Workers of magic,” said the abbess. “Master Giacomo da Varazze, the worthy archbishop of Genova and a learned Dominican, known in the Latin tongue as Jacobus de Voragine, writes of them in his book. Our confessor read us the account just this morning. They were called first, in the language of the Jews, Galgalath, Magalath, and Tharath. Secondly, in the language of the Greeks, they were called Appelius, Amerius, and Damascus. Third, in the Latin of the Church we call them Jaspar, Melchior, and Balthasar. But these names are erroneous you see.”

“I see,” said Bávlos smiling. Buonamico continued to look out the window. The abbess continued her lesson:

“Master Giacomo writes that these men were magi in three senses: First, they were enchanters. For they practiced astrology and magic on a mountain in the East called Victorial. There they worked their magic until the day that a shining star appeared to them. It shone upon them in the image of a fair child with a cross below its head. And it told them to hurry to the land of Judea, where they would find a king born of a virgin. When they eventually beheld that child, they turned from their evil ways and became Christians. Second, they were deceivers. For when they came to the city of Gerusalemme, they went to see the King Herod to ask if he knew of this newborn king. And lo, King Herod was filled with anger at the news and wanted to kill the child. But he didn’t know where he was lodged. So he asked the magi to return to him after visiting the child. And they intended to. But an angel warned them against it, and so they returned to their mountain by a different route. So you see, they were both enchanters and deceivers. But third,” she said, her eyes sparkling,”and most importantly, they were wisemen. For magus means ‘wiseman,’ and they were wise in three things: first, in heeding the star and second, in heeding the angel and third, in becoming Christian, as all good souls do.”

“So it was their feast that we celebrated today at church?” asked Bávlos.

“Well, in part,” said the abbess. “Actually, on this day four great events took place: first, the magi came to visit the infant Jesus when he was just thirteen days old. Second, Jesus received baptism from San Giovanni the Baptist thirty years later on this day as well. Third, again on this day, Jesus turned flasks of water into wine in order to help a bride and groom at their wedding. And fourth, Jesus created out of only a handful of five rolls enough bread to feed a crowd of five thousand! So it is a day in which God chose to reveal his son in various ways, and that is why we celebrate it. On this day things are revealed, and so we call it Epifania, which means ‘revelation.’”

Bávlos was confused by much of what the learned abbess said. She seemed to like to list things, and he found these hard to recall or grasp. The abbess took little notice of his confusion, however, and went on with her lecture:“But the Three Kings are especially important for you, fair sir, for they are significant to all pilgrims!”

“They are?” asked Bávlos.

“Yes,” she said. “For they were pilgrims themselves, don’t you see. Have you never seen a pilgrim’s badge?” Bávlos nodded and pulled out the shell that Father Giuseppe had given him on the coast. He had carefully bored a small hole in its base and strung it on a cord that he wore around his neck. “I have a shell,” said Bávlos.

“So you do,” said the old nun. “But there are other pilgrims’ badges as well. Wait!” She walked to a small box on a table in the corner of the room and drew out a little silver square. “Here is a badge showing the Three Kings,” she said. “I give it to you on this holy day.”

Bávlos stared at the small square of silver in the old woman’s hand. It was rectangular, with what looked like three candles on it, symbolizing the three kings and their crowns. Bávlos’s eyes turned wide with wonder and he remained completely still.

“Take it, friend pilgrim,” said the nun. Bávlos bowed deeply and took the badge from her. “You can affix it to your belt as a sign of your pilgrim status and as a plea for the Holy Kings’ help in your travels.”

“I will,” said Bávlos, his eyes welling with tears. “Thank you.”

It was deep in the night when the two men took their leave of the abbess to return to their quarters. Gállá and his sons were now high in the direction away from France, and Favtna had at last risen on the horizon that lay in the direction of the Sámi lands. Bávlos seemed lost in thought. At last he asked his friend about the badge the abbess had given him:

“Are these common in your land?” he asked; there was a note of anxiety in his voice.

“Common enough, I suppose,” said Buonamico absentmindedly, “Pilgrims use them often, if that’s what you mean.”

“But do they belong to certain families?” asked Bávlos.

“Families? No, lad,” said Buonamico, furrowing his brows, “Unless, I suppose, a man got one of those badges on pilgrimage and then passed it down to his son or grandson.”

“In my country,” said Bávlos with gravity, “This badge is known. It belongs to families in the direction of the setting sun, families with great hidden wealth, families who had Stállu for an ancestor. I have never been lucky enough to touch one and I never thought I would ever be given one as a gift.” He seemed to be nearly trembling from the fact that he held the object in his hand.

“Ha,” said Buonamico, chuckling, “funny coincidence. You say families have these badges up there?”

“They do indeed,” said Bávlos. “They are objects of great power.”

“Power,” said Buonamico with interest, “How so?”

“This badge is called Stállu Silver,” said Bávlos, “and it is said that it can be used in healing. If a part of a person’s body has been eaten by the cold, so that it turns dry and white and has no feeling anymore, you can press this badge to the spot and the warmth of life will come back to it. The heat of fire resides in such objects.”

“A cure for frostbite, eh?” said Buonamico. “Well, that makes sense, doesn’t it? These things are holy and they are bound to have miraculous effects. No doubt the Three Kings help out when you press their token onto a wound.” Bávlos was amazed at his friend’s matter-of-fact attitude. How could it be that an object of such power could simply be considered commonplace in this land? The Abbess had given it to him with barely a second thought. It seemed more evidence of Bávlos’s growing suspicion that Iesh favored this land over his own. His thoughts were interrupted by Buonamico’s words:

“But who is this ‘Stállu’ anyway?”

Bávlos shuddered at the name. Stállu was never an easy being to talk about. “Stállu is, well, he is a wanderer.” said Bávlos quietly. “That there, he said, “is his star.” Bávlos pointed into the southern sky at a bright star high above Gállá’s sons.

“That star? “ Laughed Buonamico, “Why that’s not ‘Stállu,’ that’s what we call Capella, the She-goat.’”

“No,” said Bávlos firmly. “That star is Stállu, or actually, the greatest of the Stállus, named Riibmagállis. He is guarding the Great Elk there whom others wish to hunt.” He pointed a long trail of stars across the sky below the Stállu star.

“That’s not an elk,” said Buonamico, laughing, “That’s Taurus, the bull—everyone knows that!”

“A bull, yes,” said Bávlos: “a bull elk.”

“No, lad, a bull plain and simple. There are no deer up in the sky.”

Bávlos was becoming impatient. How could it be that this stranger did not recognize an image as clear as the bull elk? “Then why does that ‘bull’ of yours have a rack of antlers?” he asked defiantly, gesturing to a sweep of stars above the forehead of the elk he saw.

“All right,” said Buonamico, good naturedly. “You call it a bull elk, we call it a bull. In any case, there it is. But you say that it is being hunted?”

“Yes,” said Bávlos, “two groups are after that elk from different sides.”

“Funny you say that,” said Buonamico, “because I have heard tell of a similar hunt for the Bull. You see those three stars down there?” He pointed to the three bright stars that were Gállá’s sons. “We call those stars the Three Kings.”

“The Three Kings?” said Bávlos, astonished. “You mean the three kings, the three magi that the Abbess spoke of today?”

“Yes, the very same,” said Buonamico: “Melchiorre, Baldassar—” his voice trailed off as he recalled the abbess’s words from earlier in the evening. “At any rate, whatever their names were, those are them!”

Bávlos was stunned. How was it that the Italians knew of Gállá’s sons, but called them three magi? Had they been Sámi? His thoughts were interrupted again by Buonamico, who was continuing his lecture about them:

“In any case, we call these stars the Three Kings nowadays, lad, but I have heard tell that in olden times, folk used to say that they were the belt of a hunter named Orione.”

“A hunter?” said Bávlos excited. Now things were making more sense.

“That’s right” he said, pointing at the bright star below Gállá’s sons. That is the hunter there,” he said, “Gállá. He is a great tracker and, along with the sun, an ancestor of the Sámi. And those three stars that you call the Three Kings are actually Gállá’s sons. They are hunting the elk together.”

“No,” said Buonamico firmly. “That star down there is the Dog Star, the top of Orione’s bigger dog. He is helping Orione attack the bull or chasing a rabbit. Those stars over there are Orione’s club.”

“Gállá is not a dog,” said Bávlos. “And Sámi never hunt rabbits. He and his sons do not use clubs. They hunt with bows, as does Favtna.”

“Favtna? Now who is he?” laughed Buonamico, shaking his head.

“He is a hunter too,” said Bávlos, “and he is right over there.” He pointed at Favtna where he was rising in the northern sky.

“Those stars?” said Buonamico. “Why, you’re right, that is a hunter, or at least in the olden times they thought so. They called him Boote, and he was said to be a hunter of great prowess. Most folk nowadays though call him the Plowman, with those stars there as his plow.”

“Those stars?” laughed Bávlos, pointing at the series of three stars that Buonamico had indicated. “Those aren’t a plow, they’re a bow! Favtna’s bow! He uses it to hunt the—”

“To hunt the elk?” asked Buonamico, shaking his head.

“Well, yes, that’s right,” said Bávlos. “Favtna is on one side trying to bag the elk, and Gállá and his sons are on the other side. Stállu is guarding the elk from them both. Favtna is the farthest away but he shoots arrows with that massive bow. Someday one of those arrows will strike that star there by mistake, the Base Star, that never moves. It is the sky nail, the single pole holding up the sky. When it is hit, the sky will fall and the world as we know it will be gone forever.”

“My boy,” said Buonamico, now very serious, “that immoveable star is Our Lady, the Stella Maris, or star of the sea. By it sailors can find their way. Our Lady watches over them, you see. There is a kernel of truth in what you say though, because the holy San Simeone predicted that Maria’s heart would be pierced by a sword. We painters always depict the scene with seven swords piercing her breast. The Three Kings, you see, are on their way to see her.” “

So is she the Star that led the Three Kings to the place of the baby Iesh?” asked Bávlos.

“I don’t know which star that was,” he said. “It was a star that moved, though, and Mary Star of the Sea never budges.”

The two men walked on quietly to Buonamico’s lodgings. Bávlos was trying to make sense of all the information he had learned. It was clear to him that the Italians had some memory of the Great Elk, even if they had come to call it a “bull” here in these warmer climes. And they remembered the sons of Gállá—the ancestors of the Sámi—as Three Kings, or magi, of whom they had made up various conflicting stories. Perhaps these magi were Sámi and the ancient people of Iesh’s land were as unfamiliar with them then as Italians seemed to be today. The confused Italians would have tried to account for their magic and their customs in whatever way they could, and the story would seem confused and even laughable to a real Sámi who heard it. Nonetheless, some of the details certainly still sounded Sámi beneath all the confusion. The magi had known stars well, for instance, something Italians apparently did not. And they knew what to do when handling a difficult person like King Herod: avoiding him by taking another way. And, of course, they were hunters as well. In other respects, however—particularly when it came to supernatural dangers—the folk of this land seemed woefully ignorant. They had turned Favtna from a demon hunter into a mere farmer, and they seemed only vaguely aware of the danger that Favtna’s bow represented to the entirety of the cosmos. Instead of recognizing the likelihood that one of his arrows would someday pierce the sky nail, they had come to associate the star with Notre Dame and described a mysterious piercing of her breast with a sword. They didn’t have any idea how this would happen, or even how many swords there would be. As for Stállu, they seemed to have called him by an insulting name—She-Goat—for so long that they did not even remember his proper name. They had no idea of the menace he represented even though they looked upon him every night as they went about their business.

As Bávlos lay down to sleep that night, it all seemed of a piece to him. The people of this land were favored, there was no doubt about it. The sun, great Iesh, was more generous with them, and he kept Favtna and Stállu more at bay. Metal badges for healing grave ills were commonplace in this land and were handed out to strangers like pieces of fat to chew on, while the same items were hoarded as treasures among families back home. Even Gállá seemed pleased to climb higher in this land’s skies than he did in the land that belonged to his descendents.

Yet, Bávlos suspected, the dangers were not absent, even if they were forgotten: Favtna continued his prowlings in this land as well. The light of the generous sun made him difficult to see, but he was there nonetheless. And therein lay the danger. When the threats are hidden, they are easy to overlook. The Abbess was right: folk in this land had a lot of misinformation in their heads. It would take much patience and work to get them to understand things properly. Thinking of the frightening specter of a rampaging Ruto, Bávlos only hoped there was still enough time to do so.