Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348

a free multimedia novel by

Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison

|

Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348 a free multimedia novel by Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison |

|

|

|

|  |

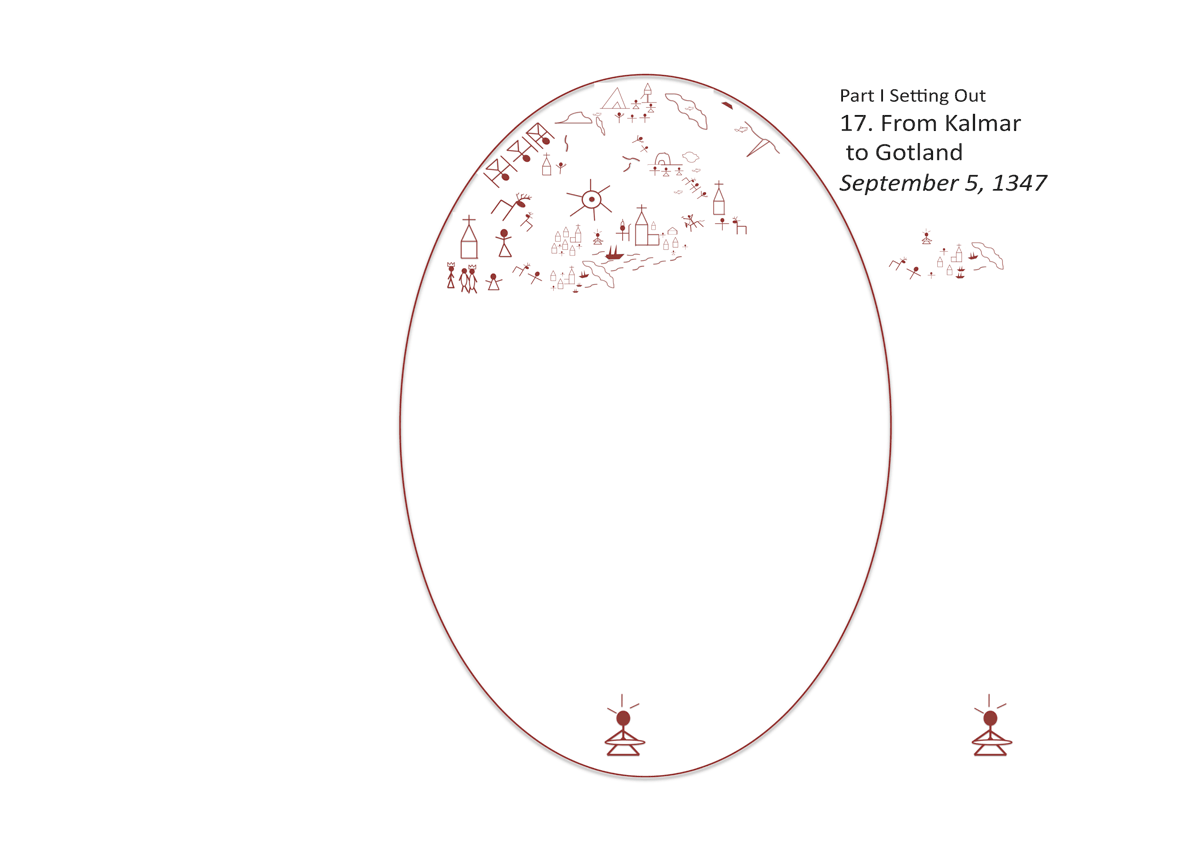

17. From Kalmar to Gotland [September 5, 1347]

Let them praise his name in the festive dance, let them sing praise to him with timbrel and harp.

Bávlos found traveling with a letter from the king entirely unlike anything he had had experienced before. The letter was like Pekka’s robe only more so: people stared at it in wonder and when Bávlos explained who it was from, they willingly gave him aid. Not that Bávlos asked for much help: he was content to fend for himself as he traveled, finding food by fishing and hunting, and making the stores of bread and cheese he had been given last for as long as possible. Nieiddash was calm again now: she didn’t mind carrying the packs and she seemed to have gotten what she needed from the grand bull that had taken her at night. Bávlos would soon know whether she was pregnant, for if she was, her antlers would remain in place all winter. If the bull had missed his mark, however, she’d be dropping her antlers within the next month. “A mother is proud when she is pregnant,” Bávlos’s mother used to say: “She wears her antlers as a sign that others should pay her respect.” Bávlos’s father had had a different theory: “She’s eating for two now, and she needs the antlers to fight off those scrounging males that would otherwise push her away from the best food.” Whatever the case, Bávlos thought Nieiddash walked with more spring in her step now, and her eyes seemed to shine with tenderness and joy.

Every so often, Bávlos asked for directions from local folk. His Swedish was getting quite good now, at least for things that he needed to talk about. Swedish words were more cumbersome than those of the Finns or the Sámi: they stuck on the tongue and stopped: they were less flowing, less tractable than the ones Bávlos had known before. And it took a long time to get used to these folk’s strange obsession with whether one was a man or woman: if you were talking about a man, you had to say han, while if you spoke of a woman you had to say hon. If you referred to the Holy Father as hon, people would twitter with laughter and wag their finger at you, and if you spoke of the Lady Birgitta as han, people roared with delight. Not only were these folk obsessed with reminding each other of the fact that people were men and women, but they extended the same qualities to everything else as well: a patch of forest was referred to as if it were a man, while an island was described as a woman. And if you were talking about the entire land, you called it simply that, a term that meant it was neither woman nor man. No one seemed to be able to explain to Bávlos why these things were so: they simply insisted it was as it was, and that anything else made no sense. Yet for all these confusing details, Bávlos found Swedish an easy language to learn and speak, and he was often surprised to think that Pekka had found it so impossible.

In all his conversations with ordinary folk, Bávlos never found anyone who could direct him to the place called Avignon: none of the ordinary people seemed in the least bit acquainted with it. At first, people told him that he must mean Alvastra kloster, a place where monks lived not far at all from Vadstena. But when Bávlos arrived there and asked for the Holy Father, the monks had laughed at him and told him to travel to the coast. Others told him he must mean a city called Ĺlborg, in a place called Denmark, far to the southwest. It was a great harbor city and the producer of much herring. When Bávlos eventually began to ask about the place called France, his questions elicited more answers, but in general, folk simply said to head east toward the coast and find a boat going that direction.

After some days of walking, Bávlos did indeed reach the sea. It was not Stockholm that he arrived at, however, but a far more prosperous port to its south, a place called Kalmar, the very town that the holy Fr. Jens had spoken of as his place of birth. There he found ships of every shape and size sailing in and sailing out, filled with those same strangers who spoke a language of their own. When Bávlos showed them his royal letter, they could not do enough for him: everyone had advice now on how to get to Avignon, although it always seemed to involve the ship of someone else. It seemed that there were many ways of getting to the Holy Father’s city, but none that seemed to begin in Kalmar. At last, Bávlos asked a particularly taciturn captain where his ship was bound.

“Not toward Avignon, that’s for certain!” said the man. “You’ll want to try my neighbor down the quay there, Hans Josefsson, he is headed that way.”

“Yes, I see,” said Bávlos, a little perturbed at this point, “but where are you headed to?”

“My ship?” said the man hesitantly, “Well, in quite the wrong direction: I am headed to Gotland.”

“Gotland?” said Bávlos, his eyes wide. At once he remembered Father Jens’swords back in Hattula and the beautiful statue of the Virgin: “Gotland is the place to go if you want to learn great art,” he had said. Bávlos straightened his shoulders and said with all the authority he could muster: “I will come with you.”

“All right,” said the captain resignedly. “We sail tomorrow. You’re not taking that beast along are you?”

“My reindeer?” asked Bávlos surprised. “Of course!” The captain had only muttered to himself in his strange language and turned away, shaking his head. “He better not eat too much grain!” said the man irritably.

“She won’t,” said Bávlos. “She is used to southern food now and can eat hay and just a little grain, just like a horse or cow.”

“Hmph,” said the captain, walking away.

And so it came to pass that Bávlos headed across the sea to the great island of Gotland, and put into port at Visby but two days later. Visby was a prosperous city, with enormous churches and streets full of life and prosperity. It had a fine castle for protection and people teamed to and fro along its bustling streets. Bávlos heard every language imaginable there, apart from his own: there was Swedish and the language of the traders, Finnish, and a language rich in beauty that people told him was Russian. There were even people who seemed to speak like Queen Blanche, singing their words through their noses. Some called the street gata, or gaya, others katu, still others straat, or shtraote or shtraase or strada. Others called it ulitsa, or ulichni, or iela. And those that sounded like the queen said rue. Folk seemed to cluster in different areas, so that in one street everyone said gata, while just a short walk away, they said ulitsa or shraote. No one seemed to mind though: the street was still the street for everyone, and they all went about their business without the least worry at all.

Indeed, everyone seemed happy the day Bávlos arrived, for it was a festival day, the feast of the birth of Iesh’s mother, the Virgin. Everyone in town was converging on a marketplace in front of a large church, where a group of men stood on a wagon. Bávlos was informed that they were going to play, and that the whole city would turn out to watch them. Bávlos found a place to stand not too far back in the crowd, which was good for him, as the Gotlanders were markedly taller than his own people: even the women were well over his height. By craning his head somewhat, however, and looking through gaps between the people in front of him, Bávlos could see the wagon and its players tolerably well.

There was a short man with a long nose, a tall man dressed as a soldier with a long red cape, a handsome man with a fancy hat and shining boots, and a teenaged boy who was dressed in a long blue gown like a woman. They were standing on the wagon and waving to the people assembled around, while another man played a cheerful tune on a small pipe that had a strident tone. All the people around them were laughing and smiling, talking to each other and occasionally calling out things to the players. At last, the short man with the long nose stepped forward to address the people. His voice was high and loud.

“Hear me folk, and listen well

What it is I have to tell!

I have an errand you should hear,

I will you each toward heaven bear.

God grant you heaven who listen well,

And save you from the pains of Hell!”

The crowd erupted with shouts and applause. They seemed wildly enthusiastic about the man’s performance and he smiled broadly and bowed right and left many times. After some time, as the applause seemed to lessen, he began again.

“There lived here once a sinful man,

Whose heart was crammed with evil plan

I will not make you long him seek

Here’s Vratislav, of whom I speak!”

The man with the big hat and shiny boots sprang forward and doffed his hat at the audience with a graceful bow. The audience now erupted with boos and and jeers. They seemed deeply displeased to see this man and wanted him gone as soon a possible. The man, however, did not seem to mind their calls but rather jumped off the stage and into their midst.

“What is he doing?” thought Bávlos, “They’ll tear him to bits!” But no violence ensued. Instead, the audience began to laugh wildly as the man ran among them, grabbing people’s hats, twitching women’s breasts, kicking boys in the behind. The first man resumed his address:

“His heart was full of evil ways

And many sins had filled his days.”

The man had climbed back up onto the wagon now, holding a purse he had snatched from a very irritated man. Then suddenly, the man on the taper played a loud note and the man with the boots froze in place. He tossed the purse back to its owner and began to circle the stage slowly. The taper’s tune now turned soft and slow as the speaker proceeded:

“But then one day he did repent

And thought of Jesus whom God sent

And hoped that he should mercy find

From our Savior meek and kind.”

The man threw himself to the ground tearing at his breast, and clasping his hands before himself while looking up toward heaven. In a moment he rose and walked in a circle, while the tall man with the red cape stepped forward, his arms folded before his chest. He held a long spear with a cross at its end. The speaker announced:

“Soon this villain to a holy man came

Saint Procopius by name.”

“Procopius, who is he?” asked Bávlos.

“Great saint of old,” said a man to his side, “lived a thousand years ago and gave his life for the faith! Folk say that he knew of the Gotlanders who traveled to Greece!”

“Gotlanders who went where?” asked Bávlos.

“Quiet lad!” said the man, “listen to the play!”

The man dressed as a soldier was now acting like he was speaking, shaking a finger at the well-dressed man and pointing at the boy in the blue dress. The speaker continued:

“'Sinful man! Seek no other—

hurry now to mercy’s mother!'

The man, he took right to this cure

And hurried to the Virgin pure.

And there he found the help he needed

So that he was to heaven greeted!”

The audience burst into shouts and applause again and the men all bowed gratefully, raising their fists to the sky as they beamed at the crowd.

“What a wonderful play!” said Bávlos. “It was great fun to watch!”

“Wait, wait!” laughed his neighbor. That was just the prologus! A kind of taste of what’s to come. Now they’re starting the play for real!”

“Oh,” said Bávlos. He could not see why the story would need anything else. “They have even more to say?”

“Yes, yes!” laughed the man. “They have a whole play to perform! Listen!”

The first man had now stepped back from where he had been delivering his address and took up his drum. He and the taper player now struck up a new tune, a lovely melody with a jaunty rhythm. The man’s drumming was unlike anything Bávlos had heard before: it wasn’t regular and swift like drumming addressed to a spirit gang, but rather leaped this way and that, like the joik of an energetic person or lively reindeer. The rhythm seemed to strike Bávlos in the back of the neck and he felt a great desire to imitate it in his limbs. The well-dressed man had stepped forward now and was standing with knee bent before the imposing figure of Procopius. He addressed the holy saint himself:

“Stand well, Procopius, holy man,

You holy scripture understand.

I’ve done all manner of evil things

I’ve robbed and lied and stolen too,

And aided the devil if I speak true.”

The audience booed loudly at the man’s words; they seemed enraged by his evil deeds and wanted him to know it. The man paused for a moment to let the cries and shouts die down and then continued:

“The world has held me in its sway.

And now I fear for my judgment day!”

Again, the crowd broke into shouts. “Hurrah!” they called. “Yes, you’ll get yours!” they cried. “You’ll have the piper to pay now Jens!” called out another. The well-dressed man turned in surprise to hear his actual came called, and all the audience laughed again at the sight. But in a moment he resumed his speech as the dastardly Vratislav:

“God’s kind mercy I now crave

That from damnation he might me save.

I come to you, I have no other,

Help me now, beloved brother!”

The audience had hushed now at the thought that the sinful and worldly Vratislav might actually repent.

“Saint Procopius will set him right,” said an old woman near Bávlos, nodding. There seemed to be a murmur of similar statements throughout the audience. The burly soldier, his arms still folded, began to speak:

“Great man, to all your sins are known

How evil in your days you’ve grown

You’ve lived your life as the devil’s thrall

And now for mercy finally call.

In cases where such evil’s been

With lives all sullied by frequent sin

For your salvation there is no other,

Turn at once to mercy’s mother!”

Again from the crowd there was a murmur of satisfaction, even delight. “Yes, yes! “ cried the old woman near Bávlos, “Mercy’s Mother! Our Lady will save the day!” She struck her palms together as if to show that the whole matter was now taken care of. In the meantime, however, Vratislav looked worried. He was shaking his head and scratching his yellow beard. He made his reply:

“Holy man, how should I go?

She will, of course, my evils know.

She’ll know I never spoke her name,

To show her honor, never came.

That I deserve hell’s fire is plain

Endless torture, endless pain.”

The audience stood with rapt attention now. The man’s words seemed to cut their hearts and Bávlos noticed an older and very wealthy-looking man wiping tears from his eyes. Procopius spoke again, more tenderly this time:

“My friend, go to her nonetheless,

And beg her humbly you to bless,

And plead your case before her son:

Hurry now, make haste and run!”

“Yes! Yes!” cried the audience in excitement, “Make haste Sir Vratislav! It’s not too late!” Vratislav leapt from the wagon and began to run among the people, calling out: “Virgin Mary! Virgin Mary!” The audience was convulsed with laughter as Vratislav stumbled about their midst asking women whether they were the Virgin Mary. He asked old spinsters and mothers with children, girls of nine or ten, and certain well-dressed women who seemed very embarrassed by the question.

While he entertained the people in this fashion, the burly Procopius clambered off the wagon and stepped briskly to an area behind. Nearby audience members clapped him warmly on the back. “Fine job, Olaf!” they said. Olaf just shook his head and hurried out of sight. Up on the wagon, the teenaged boy was standing, dressed as the Virgin, tapping a foot in impatience. Now Vratislav had worked his way back to the wagon and sprang up. He doffed his hat gallantly at the Virgin and began his speech:

“O Virgin Mary, hear me well,

For my sins I merit hell.

But humbly now I come to you,

To beg your grace and mercy true.

As mercy’s mother you are known

So unto you my hope I’ve thrown!”

Bávlos thought it a good speech, as did the rest of the audience, who was nodding and shouting words of encouragement. They seemed confident that the Virgin would respond graciously. Instead, however, the boy tossed his nose in the air as if affronted, and turned away. A gasp of shock and fear rose from the crowd. Vratislav looked out at the audience as if for moral support and then began again. He sounded more contrite this time, in fact, almost tearful:

“Good Virgin, hear my mournful tale,

And let not now your mercy fail!

Oh rue the day that I was born,

Who came so oft right life to scorn.

I know what fate my sins me earn,

But plead for me, my case don’t spurn!”

Again the audience boisterously voiced their approval for his call, but again the Virgin seemed unmoved. Not only did she remain with her back turned from him, but now she took several steps away, her head held high in seeming disgust. Vratislav seemed to crack under this apparent disapproval. In a flash he fell to his knees, and grabbing a dagger from inside his cloak, he raised it to his heart. The music behind the scene now turned loud and tense, and several women in the audience shrieked at the sight. The distraught Vratislav called out to the Virgin, the dagger now held directly above his heart:

“To plead my case I’ve no sister or brother.

Hear me now, oh mercy’s mother!

O Virgin Mary hear me true:

If you help me not, I’ll stab me through!

This knife into my chest I’ll thrust,

If I cannot obtain your trust!”

There was a pause as he said these last words and the music abruptly stopped., except for the drum, which was beating in a rapid flutter. Vratislav remained on his knees, his hand held high. As the Virgin made no move, Vratislav sighed deeply and began to pull the dagger toward his heart. The audience cried in fear and several women fell to the ground in a swoon. The Virgin seemed to hear the clamor and turned as if startled. She caught sight of Vratislav’s knife in an instant and threw her hand to her mouth. In a leap that betrayed the actor’s identity as an athletic young man, she leaped across the wagon and grasped Vratislav’s hand, knocking the knife to the ground. It bounced onto the wagon and off into the crowd, where several people leaped backward to avoid being struck. There was wild commotion from the crowd and the musicians struck up a new and frantic song, full of energy and exuberance. In a high falsetto voice, the Virgin spoke at last:

“Wretched man, why do you so?

Thought you your cries unheeded go?

My mercy was not far away,

When you approached your plea to say!

Fear not although your sins be great

For many I’ve helped in similar state

And none who to me humbly call

Unto the devil finally fall.

I will not linger with you now,

But before the Judge I’ll quickly bow

And plead your case with every haste

And earn the trust in me you’ve placed!”

The crowd burst into cheers at the Virgin’s words and the actor looked out with evident pride. Vratislav remained kneeling, hugging the Virgin’s legs fervently. With some difficulty that elicited gales of laughter from the audience, the Virgin extracted herself from the sinner’s embrace and straightened her dress. She held out one hand to Vratislav with a finger raised as if to enjoin him to wait. Then she backed slowly away. As she did so, Bávlos saw that the actor who had played Procopius had returned to the wagon, now wearing a purple rather than a red cape and with his mail shirt gone. He had painted red marks in his hands and had dabbed his beard with soot to make it black. He wore a shining crown. He stood fixed and immobile, much in the same way that he had stood as Procopius, but with his arms on his hips instead of folded across his chest. The Virgin bowed to him gracefully, rose and began to speak:

“Beloved son, oh hear me speak,

Of you a boon I humbly seek.

This man here craves your mercy mild

And repents at last his conduct wild.”

As she spoke, the Virgin gestured at the cowering Vratislav, who remained crouched behind her. Now, however, it was the Savior’s turn to look affronted, and he gravely shook his head, addressing his mother as if in utter amazement at her plea:

“That man? Mother, you know well

That he deserves the fires of hell!

My words he never once did heed,

But lived his life with sin and greed.

My help he never did implore

But vainly took my name and swore!

My love and pain he would not greet

But trampled them beneath his feet.

Blatantly, he spurned my embrace,

Never once asked for my grace.

To woman and child he did great ill,

With stolen goods his purse did fill.

His own will he loved better than mine,

Yet now he craves mercy divine!”

The audience was again moved by these words, and much grunting and head shaking ensued. The Virgin, however, was not going to let things stay this way but softened her tone and addressed her son again:

“My son, I know he did you wrong,

The list of his sins is great and long.

But as your mother I humbly plead

That from his sins he now be freed.

As once you lay upon my breast,

Hear my words and give him rest.

As a good son wishes to please his mother

Forgive this man, embrace your brother!”

The audience clambered with approval and the old woman near Bávlos shouted with delight. “Hurray for the Virgin! That’s a mother for you!” The Virgin acknowledged the audience’s cries with a little wave and curtsy, while the Savior seemed lost in deep cogitation at her words. Finally he spoke:

“O Mother mine, take no fright,

To hear your pleas is my delight.

I will grant pardon to this man

For from his evil life he ran.”

The audience now cheered with delight and it was several moments before the actors could finish their play. At last the Virgin bowed again and said to her son: “All duty and honor I tender you, and give you thanks for mercy true.” Then it was the Savior’s turn to speak. He turned to the cowering Vratislav and said: “Stand up now, man, and be you glad, for great mercy you have had! Go now and henceforth I implore Sin you not forever more!” After thundering applause and shouts, Vratislav rose and bowed again to the Savior, and then to the Virgin, saying: “I thank you Virgin kind and true Never will I sin anew! From sin henceforth I’ll turn away And long for heaven every day.” Then he turned to the audience with a final bow and shouted:

“And verily all women and men,

Do you the same, I say, Amen!”

The audience erupted again in cheers and so wildly did they jostle the wagon that the Virgin fell and her veils fell off her head, revealing the boy’s tossled yellow hair. The musicians were playing brightly as the players all bowed and waved. By all accounts, the play had been a great success. Bávlos felt that he had learned a great deal about Iesh from the play, and about the Virgin as well.