Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348

a free multimedia novel by

Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison

|

Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348 a free multimedia novel by Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison |

|

|

|

|  |

16. The Letters [September 1, 1347]

It was then that I saw a hand stretched out to me, in which was a written scroll which he unrolled before me. It was covered with writing front and back, and written on it was: Lamentation and wailing and woe!

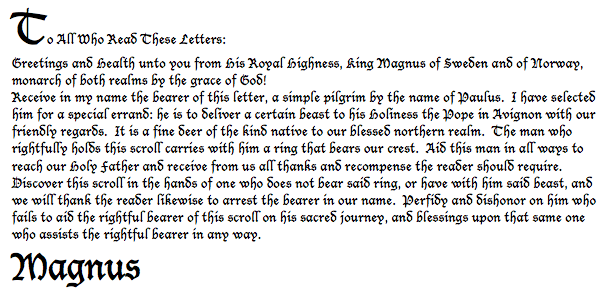

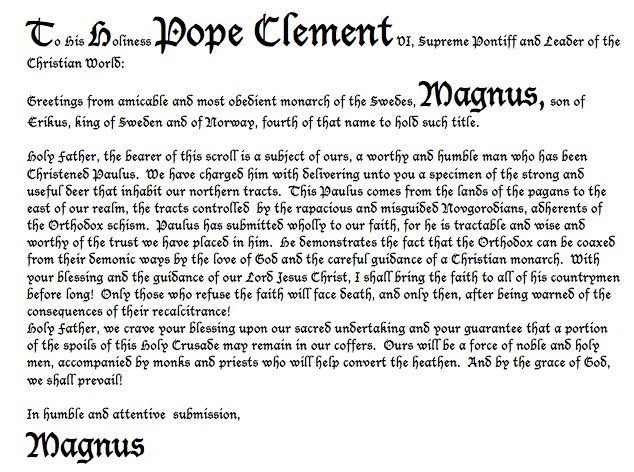

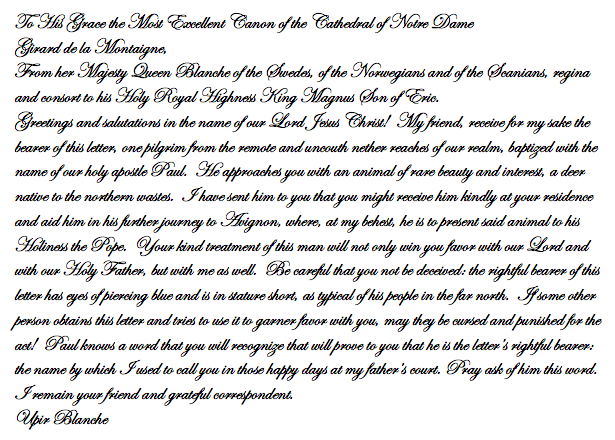

In the next several days, Bávlos was treated with great courtesy in the halls of Vadstena as work began on the promised letters. There were to be four, although Bávlos was only aware of three of them. Queen Blanka, true to her word, set about preparing a letter of introduction for Bávlos to her old friend, the canon at the cathedral of Notre Dame. At the same time, Magnus ordered the preparation of two letters, one to aid Bávlos in reaching the pope at Avignon and the other intended for the pope himself. Meanwhile, in her spartan bedroom in a separate wing of the estate, the Lady Birgitta dictated her own letter to her confessor Peter, intended for Bávlos to carry and deliver to the pope.

Bávlos found the work involved in making these letters fascinating. He recalled the letter he had received from Fr. Jens at the church in Hattula, and the remarkable way the man had been able to convey a message to the bishop through a series of small drawings. Now he would get to witness the process in greater depth and learn more about the magic or ingenuity that went into it.

Work began in the estate’s tannery. There Bávlos met a large, leathery man named Jon. He was tall and burly, with a bulbous nose and hands that were as thick and tanned by his craft as any saddle leather. It was his job to process the hides that became goods for the household: shoes, hats, saddles, bags, and, of course, pages for writing. Jon could, and did, tan anything that came his way. The calf the household had been feasting on the night before was to become a fine piece of parchment for both of the king’s letters. But Jon explained that lesser messages could use humbler skins: lambs, dogs, cats, squirrels, rabbits, even rats—all had become vehicles for written messages in Jon’s time.

Bávlos found it difficult to ask the man many questions about his craft but he learned a great deal simply by watching. Jon placed the calf skin in a wooden pot with a mixture of water and a powdery white stone so that its hair would fall out. This happened fast—strangely fast, as far as Bávlos was concerned. In a matter of days the fur pulled out of the skin with ease. Back home, pelts that were going to be turned into hairless leather were placed in a streambed to sit, sometimes for a week or two, so that the hairs gradually were loosened from the water-logged skin. Then they had to be scraped to remove the hairs that did not fall away of their own accord. Jon’s liquid seemed to do the same work in a fraction of the time, although scraping was still necessary here as well. Back home, the hide would then be placed in a bath with bark from birch trees, or sometimes willow, so that it became supple and durable. If one wanted the skin to have a reddish appearance, it was good to soak it with bark from an alder tree, for that tree’s bark produced a deep red dye when it was chewed or left in a pail of water to soak. Or, if one wanted a leather that was very white, one could soak it with fat rendered from reindeer hooves or fish grease, or in a pot with water that had been boiled a long time with hooves and bones. Jon said he did tan some things with various baths, but that the calf skin, since it was to become a sheet for writing, needed no such treatment. Instead, he tacked it on a large board to dry out in the way that Sámi did for pelts they wanted to preserve with the fur still on. Once it had dried somewhat, it could be scraped little by little, so that finally it became thin enough to meet the standards of a writer. Then Jon rubbed it vigorously with a coarse stone to smooth it down and stretched it again to dry some more. He soaked it afterward in a mixture made of another stone that accomplished the same bleaching that Bávlos knew could be produced by a bone or hoof bath.

Then at last, Jon trimmed the piece into a large rectangle, a favorite shape of people in these parts and one they seemed to favor for everything from writing sheets to doors, to houses, to tables. Almost nothing was left in its natural shape in these parts, even if the sharp corners of all these objects served little useful purpose, as far as Bávlos could tell. Indeed, in a pack or saddlebag, such corners were positively a nuisance, and they usually became badly blunted or broken in time.

Once the skin was ready to be written on, Jon sent it to Birgitta’s friend Master Peter of Alvastra, who listened to what the king wanted to say and rendered his words in Latin. This was necessary because outside of the northern lands—Sweden, Norway, and Denmark—people did not understand the king’s language. Latin, as God’s language, was known to the south, and learned men like Master Peter were expert in translating between the language of Sweden and that of God. Master Peter had much experience in this area, because the Lady Birgitta often asked for him to write down her visions, and he always did so in Latin. Magnus read the letters once they were done and inscribed them with his own name at the bottom of each. Here is what Magnus’s two letters said:

|

|

In contrast to her husband the king, Blanka wrote her letter herself, and in French. And where Magnus had ordered fresh sheets of parchment for the purpose, Blanka contented herself with having a page from a Latin Life of St. Augustine torn from a worn out manuscript, summarily scraped and readied for her use. Such was common in bookcraft: the same sheet could be used two or three times before finally wearing out. Blanka did not like the idea of dictating her private letter to her canon friend to Master Peter, and she knew that her friend would have no trouble reading the French that the two of them had spoken to each other daily when growing up in the duchy of Namur. Written documents were dangerous things, of course, as everyone knew. In the right hands they could move mountains. In the wrong hands they could prove fatal. Blanka’s own uncle Robert III of Artois had experience of the fact. He had presented a document that proved his right to the County of Artois, his father’s realm, only to have Philippe VI, the king of France and his own wife’s half-brother, declare it a forgery. As a result, Robert had been forced to flee for his life back to Namur and then to Brabant and finally to England, where he had encouraged King Edward III to lay claim on the title of King of France. The results of that mischief-making were now creating havoc on the continent, as Blanka knew only too well. So it was with great care and a certain degree of anxiety that Blanka wrote this letter to her friend:

|

When the letters had been completed they needed to be carefully rolled and sealed. The seals were made of fine wax with ribbons threaded in them. They were then presented to Bávlos in an elaborate ceremony that involved holy water, prayers and several extended speeches. The queen instructed Bávlos to remind the canon of the queen’s childhood epithet for him: Gigi. King Magnus gave Bávlos a fine golden ring with a special mark on it that he said should never be shown or given to anyone until he reached the court of the pope. This ring, he explained, would convince the pope that the letter was real. Bávlos was duly impressed by these efforts on his behalf. Although he never saw the contents of the scrolls he was given to carry, he was certain that, with their help, he would be able to do all the things these fine people wanted him to do. And what’s more, he would be able to follow the call and instructions of Iesh.

The very next morning, Bávlos sought out his friend the Lady Fina to say farewell.

“You must go quickly,” she said with a wistful smile. “God has much for you to do.” She looked away quickly as if to hide from Bávlos the tear he saw on her cheek.

“I know,” said Bávlos. “I hope that we may meet again someday.”

“I hope so as well,” said she. “Pray for me and I will do so for you. Now farewell friend pilgrim.”

“Stay well, Lady Fina,” said Bávlos. He retrieved his reindeer from the estate’s stables and left that same hour.

Unbeknownst to either Bávlos or his friend Fina, the Lady Birgitta had also prepared a letter for Bávlos. She had prepared her confessors to shave Bávlos’s head as a sign of his humility and a mark of his willingness to submit to God’s will. She had also dictated a detailed letter to the pope exhorting him to call a holy year and to return to Rome to consecrate it. But she had neglected to tell Bávlos to come to her apartments before leaving and he did not think to do so himself, so the letter was never received. Birgitta was exceedingly irritated when she learned that Bávlos had left, and it took Catharina some days of pleading and apologizing for her friend before she placated her mother. The Lady Birgitta determined to send her letter to the pope by other means and she ceased to discuss Bávlos with her daughter for a long, long while thereafter.