Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348

a free multimedia novel by

Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison

|

Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348 a free multimedia novel by Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison |

|

|

|

|  |

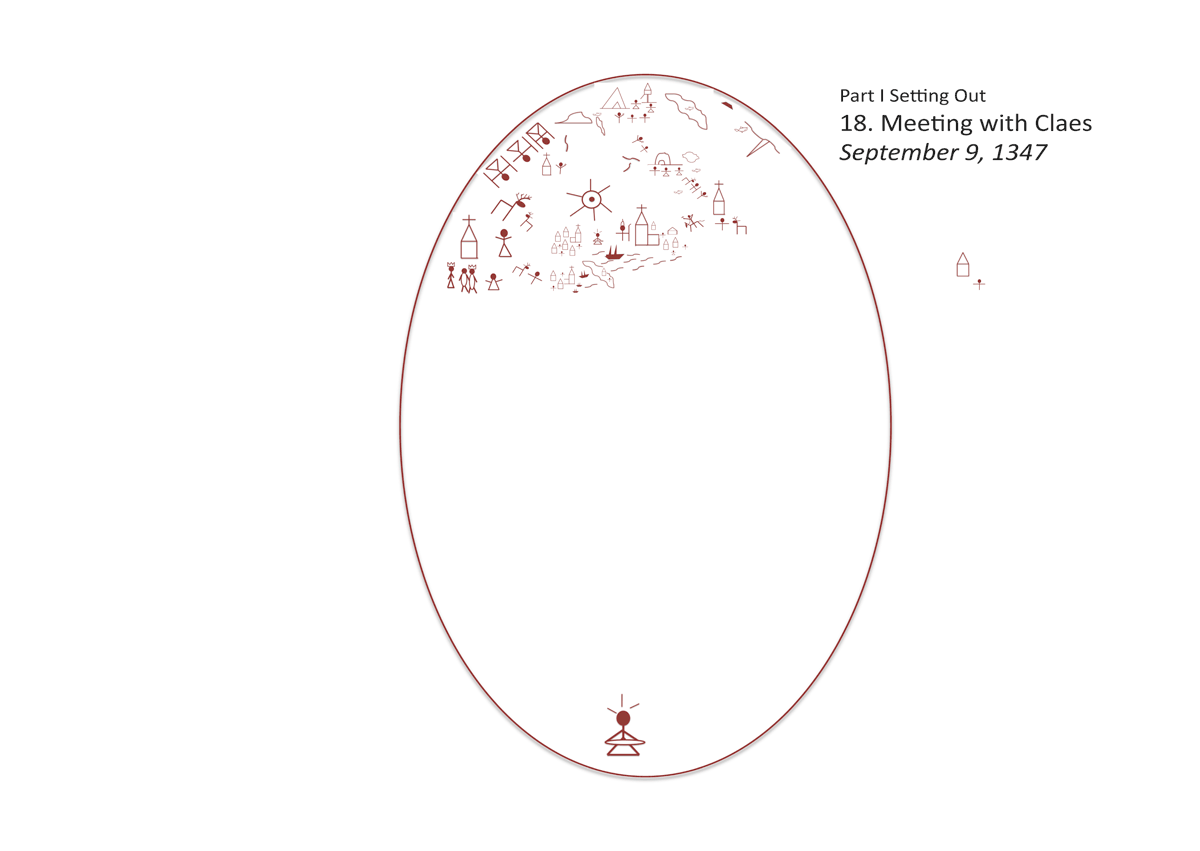

18. Meeting with Claes [September 9, 1347]

The Lord... has filled them with a divine spirit of skill and understanding and knowledge of every craft: in the production of embroidery, in making things of gold, silver or bronze, in cutting and mounting precious stones, in carving wood, and in every other craft.

The next day, Bávlos began to sort out what he was doing in Gotland. He had boarded the boat mostly out of frustration, because the captains of Kalmar had not been able to give him any good advice on how to get to Avignon. Of course, he had recognized the name of the place from the words of Father Jens and he had enjoyed his experience of the play very much, so he was glad for his choice. Now, however, he wondered how coming to this island would accomplish the task which Iesh had called him to, or the more immediate journey that the Lady Birgitta had assigned him. “Is Gotland on the way to where I am going or not?” he pondered. “Then again” he thought to himself, “what place has been obvious on my journey so far?” So many places had just seemed to arise out of chance and yet they all seemed to be building toward something greater, something that was coming. “I shall ask the Virgin to lead me next,” said Bávlos. Immediately, as if in reply, he heard a woman’s voice very close behind him. “I shall lead you indeed,” she said. Bávlos turned to see who had spoken, but found no one nearby. He started to walk the winding streets of the town: by the grand churches and monasteries, one peopled with men that wore white and black robes like those of Brother Pekka. And he came to an area of artisans, where blacksmiths, coopers, tanners and other craftsmen had their homes and workshops. Before he quite knew what was happening, he found himself before a door with a magnificently carved front. Above it was a wooden image of the Virgin, smiling down. After asking an old woman on the street, Bávlos learned that this was the door of the famed Master Claes Olsson, sculptor of church art, renowned in many lands. Bávlos timidly pushed the door open and stepped inside.

Bávlos found himself in a large front room that seemed to double as a workshop and a living room. A small fire burned under a massive chimney in a corner fireplace. In the middle of the room Bávlos saw various large tables, strewn with carved body parts: arms, hands, feet, heads. Wood chips littered the floor and chisels and mallets lay all about. Secured to a large table closest to the room’s side window was a large statue of a seated woman, partly finished. Although she had no head as yet, her hands and arms were already in place, and they were holding a small child. Undoubtedly, it was another statue of the Virgin. After some time, Bávlos noticed an old man, stooped in a small chair beside the fire, rocking back and forth slowly, muttering some prayers.

“Good day to you, father,” said Bávlos respectfully.

“What’s that?” shouted the old man, cupping a hand to his ear.

“Good day, I said,” said Bávlos more loudly.

“Ah,” said the man, staring in evident confusion. “Do you need help?”

“No, not exactly,” said Bávlos, somewhat embarrassed. He had entered this man’s house in a Sámi way, without announcing himself beforehand and assuming that he could make his introductions once inside. Now he saw that it would not be easy to talk to this man.

“Are you from Reval?” asked the man, his eyes showing a look of anxiousness that they had not betrayed a moment before.

“No,” said Bávlos loudly, “Not from Reval, from Kalmar.”

“Ah,” said the man. He sighed deeply.Bávlos moved closer so as to speak more directly into the man’ s ear.

“You are the carver Claes Olsson.”

“I am,” said the man, a look of happiness in his eyes. “At least, I was. I am still Claes Olsson, but I cannot carve anymore.”

“Cannot carve?” asked Bávlos, nearly shouting. The workshop certainly looked filled with parts to many fine sculptures.

“Cannot anymore,” said the man, wringing his hands. “Too painful. Punishment. Punishment.”

“Punishment? For what?” asked Bávlos surprised.

“My last statue,” said the man, gesturing with his chin toward the large sculpture that Bávlos had seen on the table. “Commissioned by a big man. Stig Andersen of Reval. For a church there. Church of the Holy Spirit. Wanted a Virgin. Can’t finish.” The man spoke in short fits, paring his words to a minimum and pausing a good while between each phrase. Bávlos suspected he did so because of his trouble hearing, but it reminded him nonetheless of a carver blocking out a piece. One didn’t simply attack a piece of wood from start to finish: rather, one made passes at it, roughing out the basic shape one time through, then returning to it to give it more shape another time, then returning again to add the fine details. He wondered whether Gotlandic carvers followed the same practice as Sámi in this respect, or if they had found a way to carve a piece without it cracking and splitting when too quickly hewn.

“You are letting the carving rest for a time?” asked Bávlos.

The man shook his head sadly. “Can’t finish,” said the man. “Punished. Due in Reval nearly a year ago. Big man. Much money.”

“Why can’t you finish?” asked Bávlos, “Who is punishing you?” He was beginning to find the man’s cryptic remarks irritating.

The man seemed to sense Bávlos’s impatience and breathed deeply. He was going to try longer sentences at last. “It was to be the last statue I would carve,” said the old man, “But the pains of old age have seized my limbs. I can barely grip a chisel these days.”

“Indeed?” said Bávlos. “There are angry spirits in your joints?”

“I suppose so,” said the old man, sighing again. He seemed to be hearing better now. “But why, I do not know. I have done nothing to anger our Lord, except—“ The man glanced guiltily at his statue and then turned away again.

“Except?” asked Bávlos. He could see that the story was not going to come quickly from this man.

“Well,” said the man hesitantly. “It’s the statue. Perhaps Our Lady, perhaps she—perhaps she doesn’t approve.”

“Approve?” asked Bávlos. “I have seen your statues of Our Lady before. I saw one you did for the church at Hattula and I am certain that Our Lady would be very pleased by it!”

“This one has a, a—”

“What?” said Bávlos, looking over at the statue. Perhaps there was something wrong with the piece of wood, or perhaps it was cracking already.

“A breast,” said the old man. He buried his head in his hands. Bávlos saw that they were still large and mighty-looking hands, with fingers that looked like twisted iron and great wide wrists.

“Breast?” said Bávlos. “I do not know the word.”

“Breast!” said the old man, turning crimson with embarrassment, “What a mother uses to feed an infant! Breast!”

“Ah,” said Bávlos. He looked more closely at the statue. “I see.” There, on the Virgin’s chest, over her heart, Claes had carved a slit in the woman’s garment through which a round, seemingly milk-swollen breast protruded. It was large, with a generous nipple. With her right hand the Virgin was directing the nipple toward her son, while her left hand supported the boy’s back and seemed to be drawing him gently toward her. The young Iesh’s body and head were not turned toward the viewer as in the statue at Hattula, but instead, the little child gazed happily up at his mother, wrapped in her nurturing embrace. His lips were close to the nipple and it was clear that as soon as he finished looking at his beloved mother, he would latch on to the proffered teat and suckle his fill. Bávlos thought he had the mischievous and insistent look of a three-year old who really should be weaning soon but had no intention of doing so.

“My goodness,” said Bávlos surprised.

“My goodness indeed!” said the old man, “Daring! It’s daring!”

“It’s a little surprising,” said Bávlos, hesitantly. He wasn’t sure what daring meant. “But it’s pleasant. I like it! It reminds me of when my younger brother was a baby.”

The old man did not seem to have heard much of this comment, for he simply continued to bury his head in his hands, rocking slowly. “Punishment,” said the man again, melancholy exuding with every word. “Heard about this motif from Italy. From Firenze. Saw drawings. All the rage there now. Madonna with child, big breast, milk.”

“Firenze,” said Bávlos.

“Where you go if you want to be an artist for real,” said the old man nodding.

Bávlos chuckled. “I heard that I should come to Gotland to meet you to learn about art!”

“Learn?” said the old man, his eyes widening. “You want to learn?”

“I do!” said Bávlos, delighted. He was surprised as he heard the words leaving his mouth. He hadn’t realized that that was why he had come to Gotland, but now it made all the sense in the world. Nothing—except Iesh—had ever filled him with such excitement before. The prospect of learning to make sculptures like this man’s was so thrilling to him that he could barely contain his enthusiasm. “Will you teach me?” he shouted.

“Teach,” said the old man, as if talking to himself. “You know how to carve?”

“I know how,” said Bávlos, “but I want to learn to do it the way you do!” He looked over at the chisels and hammer, which were utterly different from the tools folk used back on his father’s lands when carving a sieidi or drum. Back home they used a knife and short ax; here, to judge from the old man’s tools, they hammered at the wood with a chisel and mallet to take off pieces bit by bit. And then there were all the body parts strewn about: back home one carved a sieidi out of a single piece of wood. Here, apparently, one built the statue out of separate pieces that must somehow be joined together in cunning manner. “Will you teach me?” he asked.

“You can help me finish the statue!” said the old man, rising from his seat for the first time. Bávlos was amazed at his height. He thought that if he had seen this man in his prime he would have never been brave enough to speak to him. “We can have it done and send it to Stig Andersen! The Virgin will forgive my excess and take away my pain!”

Bávlos nodded but said nothing. He thought it was strange that the man seemed to suspect the Virgin of punishing him; it certainly didn’t seem her style, at least to judge from the play he had seen the day before or the tenderness of the statue that the man had carved. Certainly, she could act miffed for a time, but she seemed quite lenient on the whole. How could a man make such loving images of her if he thought that she might inflict pain upon him for making her too buxom?

“It is a fine statue,” Bávlos said at last, “and the Virgin will be pleased.”

Bávlos spent the evening with the old man. The man gave him some coins and sent him to a small tavern down in the center of town to bring back some food and beer for dinner. They ate heartily. It was difficult conversing when the man had so little hearing, but on the other hand, it was pleasant to simply be quiet again. It was nice to be with someone else and say nothing, nothing at all. Bávlos slept on the floor near the fire, after settling Nieiddash in the little livestock shed behind the house. Nieiddash shared the space with a nannygoat and some hens, but didn’t seem upset at the situation in the least. The man had recently procured a load of fresh hay for the goat, and it seemed to Bávlos that Nieiddash was content to spend the evening in the shed munching lazily and enjoying in her own way the silence of her conversation partners.

The next morning, work began in earnest on the sculpture. The old man seemed utterly revived by the prospect of being able to finish his work, even if he sometimes winced when he looked at her breast. The pains in his hands prevented him from even lifting a chisel, but he shouted instructions to Bávlos and demonstrated techniques in the air, pretended to hammer or cut or file. Bávlos followed his instructions readily. He used a small three-sided chisel to cut divets in the child’s head so that it looked like he had long, flowing locks of hair. He removed small areas of excess wood under the child’s chin and between the Virgin’s fingers. And then he began chiseling the elaborate folds of clothing that were to dominate the lower part of the statue down to the space which the artist had left for a protruding shoe. It was good to be carving again, and he crooned a joik for carving a sieidi that he had heard his father sing many years before:

“Supple wood, fine wood,

lo, lo looo, looo, lo; lo, lo, lo looo—

bring health to the carver and user—

lo, lo loo, looo, looo, lo.”

Bávlos found the new tools very effective but he was surprised by the wood: it was far harder than anything he had ever carved before. “What kind of tree is this?” asked Bávlos.

“Oak!” said the man. “Good wood.”

“Oak?” said Bávlos. The man touched his nose as if to say that he understood Bávlos’s confusion and pointed at a large shading tree just outside the window. It was an immense and heavy looking tree, with massive, solid branches that twisted outward and upward but never seemed to bend in the breeze. The oak was a tree that did not grow in the far north, although Bávlos remembered seeing a grove of such trees on his way to Turku. He had also seen many such trees near Vadstena.

“Oak lasts,” said the old man smiling.

“I should think so,” said Bávlos to himself. His hands were tired from a day of carving. Still, it was exhilarating to watch the Virgin emerge from the surface of the wood. The old man had hollowed out her back, no doubt at the beginning of the process, with strokes that were wide and random, as if he had used a short ax or large chisel. This hollowing meant that the statue itself was actually a fairly thin shell of wood rather than a solid piece, almost as if it were a loaf of bread from which someone had surreptitiously scooped out the middle. It occurred to Bávlos that a carving done this way would have much less chance of cracking, and he admired the ingenuity of the old carver.

Bávlos also admired the head of the Virgin, which the man had produced sometime in the past and which Bávlos now readied for attachment. She was not to gaze down at her child, as Bávlos had assumed, but was rather to look out at the viewer, as if one had just startled her from her private ministries to her child. Her eyes were widely set apart, like Elle’s, and she had a wide and smooth forehead, with no wrinkles of care or worry. She looked barely over sixteen, with soft features and a small, shy smile that seemed to say that she was not upset at being interrupted. She wore a wimple like Swedish women, but locks of hair were visible as well, curving gently alongside her neck. She had the same open and friendly air that Bávlos remembered from the statue at Hattula, one which this same artist had made perhaps a score of years earlier.

The old man was insistent that the Virgin’s garments would have all the many folds and creases and wrinkles that Bávlos had come to expect of Christian statues. Here Bávlos had to follow the old man’s instructions carefully, as he pointed to places that needed digging out, or spots where a fold had to be extended or made more distinct. Often Bávlos had little idea why he was carving in a particular place or manner, but gradually, his eyes would come to recognize the folds that the old man had planned or perceived in the wood all along. It was inspiring to work in this way, and Bávlos hardly noticed the passage of days. After some five days, he and Claes had finished the sculpture itself. The various body parts had been pegged into place, with their seams first painted with a wondrous mixture of soft cheese and a stone powder called chalk that dried into a remarkably hard and unbreakable surface. They used this substance to glue the various parts of the sculpture together, after which Claes showed Bávlos how to carefully insert small nails into key joints for reinforcement. The nails were set deep into the wood so that they would not poke out, and Claes covered each with a small piece of tin so that rust would not stain the wood or paint later on. He fit the Virgin with a small, wreathlike crown made of copper. They glued and nailed it into place so that no one would deprive the Virgin of this mark of her royal status in the future. Then Claes had Bávlos coat the entire statue with layer after layer of the glue, heated so that it became finer and easier to apply. He seemed to want to encase the rough and thirsty surface of the wood in a kind of stony coating that would make it impervious to the passage of time. Over this, they painted further layers of glue mixed with more chalk and a great deal of water. Claes explained that he had let the mixture sit for a great while until it consented to become smooth and tractable. At first, they kept the mixture fairly thick and coarse, but the further addition of water made subsequent layers thinner and finer, until at last the surface of the statue seemed startlingly smooth and fresh, almost like the supple skin of a child’s forearm.

“Now for the painting!” said the old man triumphantly. He looked jubilant, and even the sight of the Virgin’s breast seemed to cause him no concern anymore. Claes boiled a mixture of bones, cartilage and fur which Bávlos had collected from the tanner nearby to make a sticky substance which would serve as paint for the work. Claes showed Bávlos the many bags of fine powder that he had for this purpose: each different in hue or intensity. He carefully mixed portions of the powder with the gel made from the bones and cartilage and applied it to the statue with fine brushes. Bávlos did much of the painting under the watchful eyes of the master, giving the Virgin clothing of red and blue, tinting the copper of her crown gold, providing her with yellow hair and the lad with brown. Claes’s careful mixture of white, yellow and red made the skin color that Bávlos applied to the faces and hands of the figures. Each layer of paint, each color had to be applied, then let dry for a day or two and then touched up. Compared to the carving, this part of the job was easy, but it demanded time and patience and there was no rushing the process.Although his hands remained in pain, Claes insisted on doing the finishing details of the faces of the mother and child himself, coloring their lips a tender red, giving them blushed cheeks of rose, painting on arching eyebrows and pupils of blue and green. When Bávlos saw the skill that went into these details, he was glad that the artist had decided to execute them himself. When the paints had all been applied and dried for some time, Claes had Bávlos paint over them all with layers of the clear bone and cartilage mixture. After that came a final varnish made from hempseed oil boiled with pitch from pine trees. This varnish gave the surface of the statue a bright and shiny appearance, while sealing the colors in so that they would not flake away with time. “You must think of the ages when painting,” said the old man to Bávlos. “A statue must last until Our Lord comes again.”

When the statue was at last completed, Claes looked like a new man. The anxieties of not having finished his work had disappeared, and he invited everyone in the neighborhood to come and see his product. Their admiration for the statue filled him with joy, and although it appeared that his hands were still painful, he did not seem to mind as much anymore. “Our Lady sent you to me,” he said to Bávlos. “So that we could finish this piece together.”

Bávlos smiled and nodded. He was certain that the old man was right.

“Now you must take her,” he said, gazing at the statue with affection, “to the church where she belongs. The Church of the Holy Spirit, in Reval.”

“Reval?” asked Bávlos. “You want me to take her there? I—I cannot!”

“You cannot expect me to go, can you?” said the old man insistently. “I am old and not good upon the sea.”

“This Reval lies beyond the sea?” asked Bávlos. He was already a little more intrigued at the prospect, although the notion of finding this church and the great Stig Andersen sounded quite impossible still the same.

“Beyond the sea, yes, “ said Claes. “Reval is part of Denmark. It lies to the southeast of here, a couple of days’ sailing from Visby.”

“But doesn’t Denmark lie to the southwest of here?” asked Bávlos. Folk had told him that Ĺlborg lay to the southwest of Vadstena, and he knew that Gotland was far to the east of either of them.

“Not this part of Denmark,” said Claes. “It lies to the southeast. Listen, Bávlos, I need your help. I will give you the letter and agreement from Stig Andersen to take along.” He hurried to a chest in the far corner of the room and returned with a letter. He pointed at a place on the letter where someone had drawn the amount of money Master Claes was to receive for the work. There was a long line of men with their arms and legs spread wide in amazement, followed by some lines that looked like a series of fence posts such as folk placed around fields back in Sweden. “They will pay you this much money for this statue and I will be able to pay my debts. Then I can rest in my grave peacefully knowing that the statue has reached its buyer.”

“But my reindeer,” said Bávlos. “Shall I take her with me? Is this Reval on the way to Avignon?” It was the first time he had mentioned the city in the weeks that he had been in Gotland and a twinge of guilt rose in his conscience.

“Avignon? The city of the pope?” said the old man. “No. To get there you should return here to Gotland and take another ship to Lübeck. From there you can reach Avignon by land.”

“I see,” said Bávlos thoughtfully. This was the first solid information he had received about how to actually get to the Holy Father’s city, and he was grateful to the man for telling him. But the route lay apparently in quite the opposite direction from Reval.

“Please, friend Bávlos,” said the old man, wringing his hands. “You can be there and back in less than a week and I will care for your reindeer while you are gone. I will pay for your passage there and back with the earnings from the statue!”

“I see,” said Bávlos again. It really did seem to be the right thing to do. The eyes of Claes’s Virgin seemed to silently tell him so.

“All right, I’ll go,” he said. “Stig Andersen shall have his statue at last!”