Chapter 18. Meeting with Claes [September 9, 1347]

Cultural Explanations

|

Chapter 18. Meeting with Claes [September 9, 1347] Cultural Explanations |

|

|

In this chapter Bávlos assists Claes Olsson in finishing a statue of the Virgin for a church in Reval. | ||

| Claes Olsson and his workshop |

In this chapter, we see Bávlos tracking down the artist who had made the statue of the Virgin at Hattula. Although we know that the Hattula Madonna was made in either Gotland or Lübeck, we don't actually know the name of the artist responsible, and Claes Olsson is a fictitious character. But the techniques presented in this chapter of carving, finishing, and painting a statue are entirely accurate. They are drawn from a variety of sources, but a good overview text is Daniel V. Thompson's The Materials and Techniques of Medieval Painting (New York: Dover Publications, 1956).

Bávlos is depicted wandering through the streets and hills of Visby, arguably Sweden's best preserved medieval town.

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

| Visby street scenes |

Master Claes has made a statue with a suckling Jesus, a motif that art historians know as Maria lactans ("the lactating Mary"). This portrayal of the Virgin took shape in Tuscany in the late thirteenth century and early fourteenth, and can be seen in various paintings in cities like Siena, Florence (the "Firenze" mentioned in this chapter), and Pisa. It accentuates the human, innocent, dependent nature of the infant Jesus and is closely associated with a growing devotion among the laity of the time for both Christ's blood and Mary's milk. One would expect this motif to take a long while to reach Scandinavia, yet a wooden statue with the same imagery was produced by a Swedish artist in Småland at precisely the same time.

|

| Edshult Madonna |

The infant's curly hair and the Virgin's sprouting breast seem to point at the idea that the Swedish artist knew of the latest artistic fad in Tuscany and sought to reproduce it in wood for a Swedish church. Compare the close-up on the Swedish statue with more-or-less contemporary paintings from Siena:

|

|

|

This startling similarity lies behind my image of Master Claes having created a lactating Maria as his final work.

The various techniques of production and finishing discussed here are all typical of medieval wooden sculptures. Artisans tended to hollow out the pieces of wood they used so as to reduce the likelihood of cracking--the scourge of all wooden sculpture. They also constructed their works from composites of different pieces, each individually carved by a craftsman or apprentice. The parts were then assembled, nailed and/or glued in place, and then coated with layers of gesso, paint, and varnish. The end result was marvellously smooth, much like fine marble, and nothing like what modern hobby carvers like to imagine as "folksy" carving. Compare my close-up on an actual medieval carving from the fourteenth century below with a modern "reproduction" done by a carver of the 21st century. For some reason, artists like to imagine that medieval art was rustic and naive. It was not.

|

|

| A well-preserved example of a medieval carving | Modern imagining of a medieval carving |

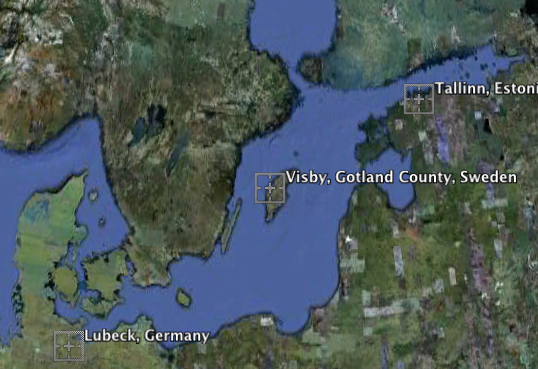

The Reval of the text is the city known today as Tallinn, capital of Estonia. As this map from Google Earth shows, Tallinn lies in exactly the opposite direction from Lübeck, the port that will lead Bávlos toward Avignon. But Bávlos cannot let his teacher and friend down, and so, he determines to leave Nieiddash behind and take a short detour to the eastern possession of the Danish crown, Estonia.

|

| Image courtesy Google Earth |

Master Claes writes the amount he is expecting to receive for his statue from the man who commissioned it, Stig Andersen. Bávlos perceives the sum as a series of astonished men and fence posts. Of course, he is viewing a number composed of X's and I's. In school you may have learned that the number 46 is written in Roman numerals as XLVI. Remember? It took me a long time to learn those rules for writing Roman numerals, and I still find them irksome. In medieval account registers, however, one seldom finds that sort of thing. The number 46 would be written XXXXIIIIII, plain and simple. From Bávlos's point of view, such a number would certainly seem like a row of astonished men and a long line of fence posts.