Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348

a free multimedia novel by

Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison

|

Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348 a free multimedia novel by Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison |

|

|

|

|

|

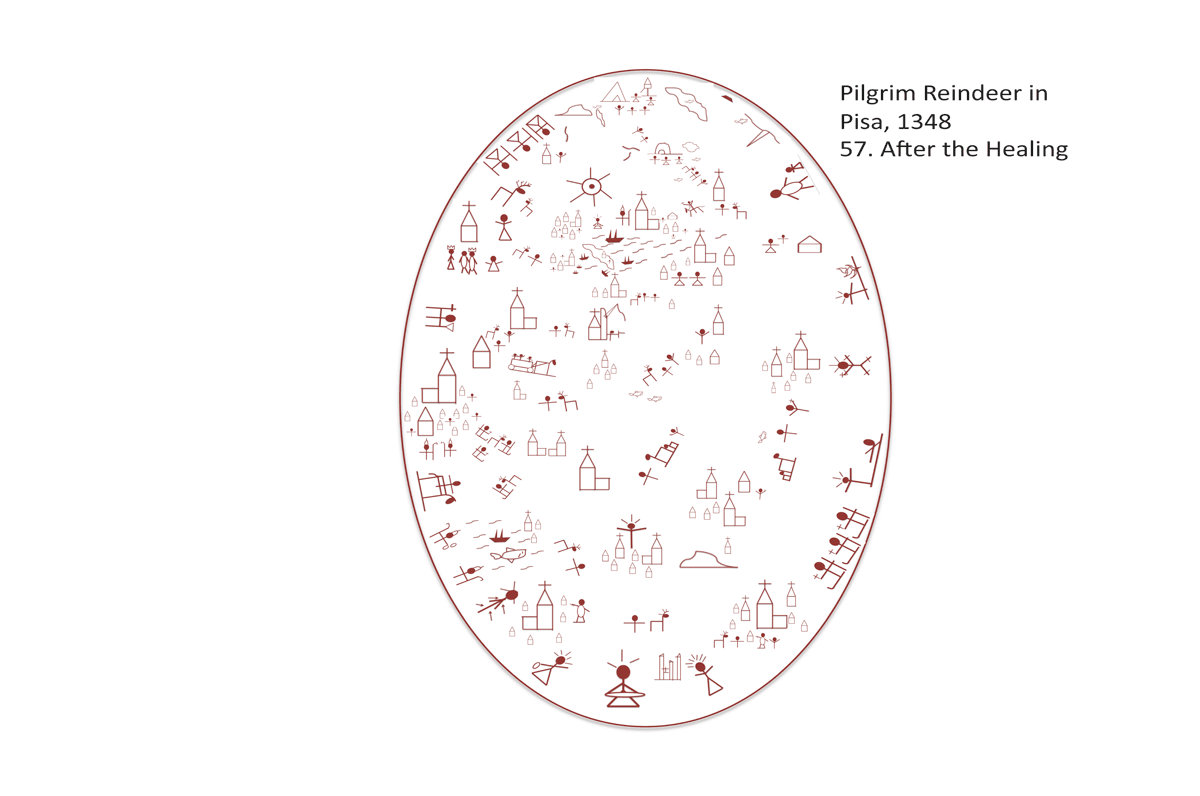

59. The Reckoning [July 27, 1349]

Lord, when did we see you hungry and feed you, or thirsty and give you drink? When did we see you a stranger and welcome you, or naked and clothe you? When did we see you ill or in prison and visit you?

No sooner had Buonamico finished his work than the dignitaries began to arrive to inspect it. Such had always been times of pride and flourish for Buonamico but now no more. His fresco was a memory of a world torn apart: a harbinger of the destruction awaiting all unless they hasten to change their ways. Most personally, for Buore ustit, it was a memory of a friend who had saved his life and who was paying for it with his own.

Among the very first notables to arrive for a viewing was an entourage from afar: the holy Lady Birgitta Birger’s Daughter, kin to Magnus Eric’s Son, King of Sweden and Norway, sometime advisor in holy and queenly living to his young bride Blanche of Namur. She was staying in Rome on pilgrimage for the coming Holy Year, but in response to a vision, had journeyed north to a monastery in Farfa, near the city of Bologna. Now, on her way back to Rome she had come to Pisa, to see its holy sites. Birgitta arrived with a small party: no more than five attendants, along with her two holy confessors, Master Peter Olafsson of Skänninge and Master Peter Olafsson of Alvastra, and her daughter Catharina Ulf’s Daughter, wife of the noble knight Eggard von Kürnen.

The surviving clerics of the Camposanto had been abuzz at their arrival, for Birgitta was known to be an exceedingly pious lady, and no one knew what sort of donation she might make if she was moved by the things she saw. They nearly twittered with anticipation as Birgitta surveyed the various holy images of the complex, coming at last to Buonamico’s newest fresco. She had looked upon it with seeming interest, then suddenly clutched her chest and fainted. Her attendants bore her back to her lodgings, where she remained indisposed for the rest of the day.

On the following morning, Birgitta sent an urgent request to the bishop for an immediate audience. The archbishop was away, but his assistant Bishop Luigi, eager to reap the benefits and hear the praise of his superior choice of artists, agreed to meet with Birgitta that very afternoon after lunch. He invited Birgitta to lunch as well, but her messenger politely declined: she would be fasting that day as usual. The artist Buonamico had also been invited to the meeting.

That afternoon, the two parties converged with all the dignity and grandeur expected of the assistant bishop of one of the greatest cities of Christendom and a member of the extended royal family of Sweden. Birgitta arrived with her two confessors, her daughter, and two other attendants. She spoke in Swedish, interjecting when she could phrases in Latin that she knew from her prayers. She relied on her confessors to translate for her: they spoke a rather stiff and bookish Latin, little colored by Italian pronunciation and mannerisms in the way of local clerics. Yet it served well as a medium in audiences of this kind.

The bishop, clothed in his finest apparel and wearing a chain that expressed both magnificence of his station and the riches of his city, extended his hand to Birgitta and said: “Good Lady Birgitta of Sweden, I take pleasure in greeting you.”

“Et cum spirito tuo,” said the small noblewoman, bowing to kiss the ruby of his ring. The gesture seemed to please the bishop greatly and he found her use of Latin amusing. Birgitta straightened back up and rather primly wiped the creases from her austere black robes. She wore a black habit and a black wimple, with only a small touch of white linen encircling her face. Her hands were devoid of rings and her face looked somewhat ashen and worn.

“Master Peter Olafsson of Alvastra” she said in a businesslike way, “you shall stand by me and act as my translator with his excellency the bishop. Master Peter Olafsson of Skänninge, you stand beside my daughter Catharina and help her converse with the artist Buonamico. She is anxious to make his acquaintance.”

The men instantly complied and the party split in two. Buonamico found himself being ushered toward the side, away from the bishop and the elder woman. He felt relieved at not having to make pleasantries with the bishop, whose glance he studiously avoided, and not a little relieved as well at being able to step away from the Lady Birgitta. There was something indomitable about her, something hard as steel. Her eyes seemed to cut like knives and Buonamico felt certain pangs of guilt for all his past wrongs and follies. Her daughter on the other hand, was youth itself in all its glory: tall and willowy, blond and fresh, not even twenty yet, from what the artist could tell, and possessed of eyes of radiant blue that she demurely bent toward the ground. She was a flower, thought Buonamico, who would serve excellently as the very model of the Madonna, were she dressed in blue rather than the plain gray she wore that day.

Birgitta turned to her confessor. “Good Master Peter Olafsson. You must tell this bishop every word I say. I had a vision yesterday before this painting, and I cannot rest until its message is delivered.” She had said the word vision with great emphasis and Peter had seemed to quiver at its sound. As she turned to address the bishop she seemed to rise out of her tiny frame like a lion.

“Indeed, ma’am, I shall gladly interpret for you” said the cleric quickly, bowing his long, narrow head and fairly trembling in her presence.

“Do then, let us begin. Good bishop,” she said, pausing again to straighten her wimple and wiping an imaginary wrinkle from her sleeve, “I must tell you that your sordid sins, your bloated, gaudy, whoresome perfidy reaks unto heaven and threatens to bring upon you the damnation you so rightly deserve.”

“Good your Excellency holy Bishop of Pisa,” began Peter, somewhat diffidently, “ the holy Lady Birgitta wishes to convey the contents of a vision she had yesterday before this very image. In it, she sensed that, that, certain irregularities, occasional excesses, if you will, may have occurred within your diocese, and these have, to a certain extent, lessened the well-earned high regard of our Holy Savior for, so to speak, some personages within your see.”

“Yes?” said the bishop, somewhat surprised at this opening. He raised his eyebrows as he fingered his jewel encrusted chain. Birgitta watched him closely for any signs of remorse. “Continue.”

“An angel spoke to me from this painting: that angel there, on the right, and said that you are a foul and ignominious ruffian, who whores it up with concubines right and left and steals from the church to pad your easy living and vapid pastimes!”

“The holy Lady Birgitta received a communication from an angel in which, er, some persons of rank in this diocese, certain persons of great talent and tremendous responsibility, have, perhaps, owing to the pressures of their duties, shown a certain laxity regarding the precept of priestly chastity and the proper—I should say fastidious—management of ecclesiastical funds.” Again the bishop stood immobile.

“I say Master Peter, are you translating my words?” Asked Birgitta, somewhat perplexed. “I do not seem to be making much headway showing this villain his villainy!”

“I am, ma’am, “ said Peter quickly, “I am. It is only that Latin lacks some of the earthy directness of our language. I must find means of expressing your thoughts in this most flowery of foreign tongues.”

“I see,” said Birgitta. She sucked in air and grew more rigid still, then looked directly into the bishop’s eyes. With one hand she pointed at a man in the picture, a cleric, whose soul was being wrenched out of his body by a bat-winged demon. With the other hand she pointed directly at the bishop’s chest. She said: “Peccatorus! You are a peccatorus! You are a fat, useless, evil man! You will be skewered and burned for all eternity, drowned in demon’s feces, your skin peeled from your worthless flesh!”

The bishop needed no translator for this remark. The Latin term for sinner, the pointing, the vehemence of the woman’s scowling diatribe—all were too amply clear for any attempted softening from poor Peter. The bishop stiffened and frowned. Affronted but wishing to remain dignified, he murmured: “The audience concludes” and turned at once to leave.

“Deo gratias.” Said Birgitta as she watched him stalking way.

Meanwhile, Buonamico and the Lady Catharina were having a different sort of discussion. They seemed to like each other from the very start.

“You have made a painting that can touch the hearts of all who are fortunate enough to look upon it,” said Catharina. Her interpreter translated her words into Latin.

“Thank you,” said Buonamico in Italian, a little of his old bravado rising to the surface. But no, that was of the past: he suppressed his glee and furrowed his brow, saying: “I have not made this painting for praise of men, however gracious that praise might be, and however sweetly delivered. This painting is a document of the pain our city saw: a reminder of the brevity of this life.” Though he spoke in Italian, the cleric seemed to understand his words, translating them into a murmured Swedish. Even before hearing the translation, though, Catharina seemed to know his mind.

“Indeed,” said Catharina. She sighed. “It must have been horrible to see so many die so quickly.”

“Indeed it was,” said Buonamico quietly. He looked down and Catharina could see that tears were in his eyes.

Hoping to divert the poor man’s attention somewhat she said: “Can you tell me about this curious figure in the corner, Master Buonamico? I am but a humble woman and from very far away, so the symbolism of the image is lost on me, I fear. Pray why is the monk stooping there to take milk from a deer?”

“That’s no symbol, “ said Buonamico, lifting his head. “It happened like that. I drank milk from the teats of a deer and it saved me from the Plague. Or at least, drinking it convinced God to spare me for another day.”

“But how, “ said Catharina in puzzlement, “how on earth did you hit upon the idea of drinking deer milk?!”

“It wasn’t my idea, my lady,” said the artist, “It was his: a friend named Bávlos gave it to me.”

“Bávlos,” said the woman. She seemed suddenly to be breathing faster. “Bávlos did you say?”

“Yes my lady, Bávlos. And come to think of it, he was from a land near yours I suppose. He is, or was, what Tacitus called a Fennus.”

“A Fennus? Here?” Catharina seemed agitated now. “In my land, yes, far to the north, there are people who keep reindeer as cattle and who live by hunting and fishing. I once, for a brief time, knew one myself.”

“Do tell, my lady. Yes. This Bávlos as he called himself was one of the same. He had come to Pisa on pilgrimage I take it, and alas, he is soon to die.”

“To die?”

“To die, my lady.” All at once Buonamico found himself becoming animated, speaking a truth that he had thought he could speak no more until his dying day. He spoke rapidly now, and the cleric could barely keep up with the translation that he hurriedly whispered to the woman. “I knew that man and I loved him and he was the truest friend a man could ever have. When the Plague was raging and all the world thought only of itself, this man came back to find me and he brought me milk with herbs in it and he brought me back from death. Back from death, my lady, he brought me back from death. And I have made a tribute to him in this corner of the fresco: that is me there with the deer.”

“But you said that the man brought you the milk,” said Catharina. “So then, why have you painted yourself milking the deer?”

“Had to do it like that, my lady,” said the man, looking downward. “Bávlos is set to be executed tomorrow for witchcraft and it wouldn’t be permitted that I should paint his image upon this wall.”

“Executed? But why?” Catharina looked distressed now. Something in Buonamico seemed to awaken at her distress. Was this a source of deliverance? Could the terrible event be prevented? He spoke with more excitement now.

“After the Plague, my lady, people looked for someone or something to blame. ‘It must be the Jews,’ they said, or ‘It must be the Friars.’ A lot of fingers were pointing at the bishops and high leaders of the church…” as he said this, Buonamico glanced at the other party, where, suddenly, he noticed that the Lady Birgitta was pointing at the bishop herself. “My friend wore a Franciscan habit and he was known for having many miraculous things happen around him. I saw some of them myself—things I’d painted for years without blinking an eye about, but when you see them happen in front of your very nose, it’s different. And then there were the stigmata…”

“The stigmata?” said Catharina, her eyes widening further.

“Yes my lady, the stigmata. He had them. Got them after going to Assisi. And even with holes in his feet he hobbled all the way back to Siena to save me from the Plague.” Buonamico was crying now, crying without restraint. The bishop had turned to leave and Birgitta and her confessor were talking together in some agitation. Catharina reached out to place her hand upon the old man’s shoulder.

“Tell me, friend Buonamico, were this Bávlos’s eyes blue?”

“They were, my lady, as blue as a sky in springtime. As blue as yours.”

“And did his reindeer, did she have ribbons in her ears?” “She did my lady, she did!” Buonamico seemed cheered by the memory as he raised his eyes to his painting. “I thought it too strange a detail, otherwise I would have painted them in.”

“Buonamico, can you take me to this person? May I see him?”

“Madam, I will try.”

It was the middle of the night when Bávlos was awakened. A hand touched his shoulder in the dark. A figure stood before him, a figure like a woman, holding a candle. All at once Bávlos noticed that his chains had been undone.

“No words!” whispered the figure, placing a long finger to her lips. “Come.” Before he knew what was happening, Bávlos found himself being escorted through the hallways of the prison. The doors were all unlocked but no guards were anywhere to be seen. The figure at his side stepped in silence, like a cat. She seemed to know precisely where she was taking him. They passed outside into the fresh air, the first Bávlos had breathed for many months. The sky was wide above them and Bávlos saw the three skiers of the Gállá high above. “It must be almost morning,” he thought. They neared the city gate and he saw it open for them, seemingly by itself. There were no guards anywhere in sight. They walked out of the city and turned into a stand of trees.

Bávlos looked at his deliverer now: it was St. Fina. Knowing that she might immediately disappear, he humbly bent to the ground before her and said in his own language “Giitu. Thanks.” As he opened his eyes, he expected her to be gone. But no, she was not gone. The lady stood there smiling, her hand extended out to him.

“Arise, my friend. It has been a long time since we saw each other.” At the sound of her voice, Bávlos’s heart leaped. It was not St. Fina this time but her twin. “Fina,” he said, “It is you!”

“Call me Catharina,” smiled the woman. “That is my name. I have thought of you so often. And yesterday I heard of the wonderful thing you did for the artist Buonamico. How brave you have been: how did you ever manage to come all this way to Italy?”

Bávlos rose and shrugged his shoulders. So much had happened. So little could be explained. “I have nearly become a Franciscan,” said Bávlos.

“I can see that you have become holy,” said the woman, glancing at the marks on his hands, where dull scars of former wounds still marked his palms. She had looked at them more carefully when undoing his chains. “Or rather, the holiness that you have always had inside has come to the surface.”

Bávlos paused, then said: “How have you freed me, Catharina?”

“I have made a generous but secret gift to the city and it happened that, at the moment that the mayor summoned his soldiers to his office to hear the good news, you managed to slip away.”

“Like St. Zita,” said Bávlos thoughtfully. “Yes, if you will,” said Catharina. “They knew it was not your fault. God was in that Plague, not human magic. But now you must hasten away, for the bishop is expecting to have you executed this morning, and I’m afraid he’s unlikely to take your absence kindly under those circumstances.”

“Indeed,” said Bávlos. “I will away.”

“Where will you go?” asked Catharina suddenly breathless, aware all at once that she would not likely ever see him again. “First to Mount Morello,” said Bávlos, “to see Nieddash and her calf. A fine male. I called him “Admirabilis.”

“A calf, how wonderful! And then?”

“I don’t know,” said the man, his eyes suddenly sparkling. “This land is strange. It teems with people: more than I ever thought possible in a single place. And yet, at the same time, there are mountains and hillsides that no one bothers with: places where wild pigs run free and game is plentiful all year. I might take up a hermit’s life; some do, you know. Or perhaps I will go back to Assisi and work with the brothers there, or even head home to tell my people what I’ve seen. I guess I’ll wait for Him to tell me.”

“Him,” said Catharina.“Yes, him. I expect he’ll have more for you to do.”

“And for you!” said Bávlos cheerfully. “Look at you! Who would have thought you’d ever be here as well!”

“Oh I’m only here on a visit,” said Catharina. “I shall go back to Sweden in a few months.”

“Indeed?” said Bávlos. “We shall see.”

“At any rate,” said Catharina, smiling. “You must hasten now, and I must back to my mother, for she rises early and we have prayers to say. Farewell.” Even so, she hesitated, somehow unwilling to leave the spot.

“Catharina,” said Bávlos uncertainly, “I know you are a married woman and I a Franciscan brother, but—”

“But,” answered Catherina, “can we embrace?”

“Yes, Catherina. As brother and sister, can we embrace?”

“Of course my friend.” They took each other in their arms and warmly hugged. Bávlos lay his nose along hers in the Sámi way, and she puckered her lips to his cheek in the manner of the French. Both felt somehow like crying, and when they drew apart, they both wiped tears away.

“Go in health,” said Bávlos.

“Stay in health,” she replied. Bávlos watched her from behind as she picked her way out of the forest and strode back toward the city gate.