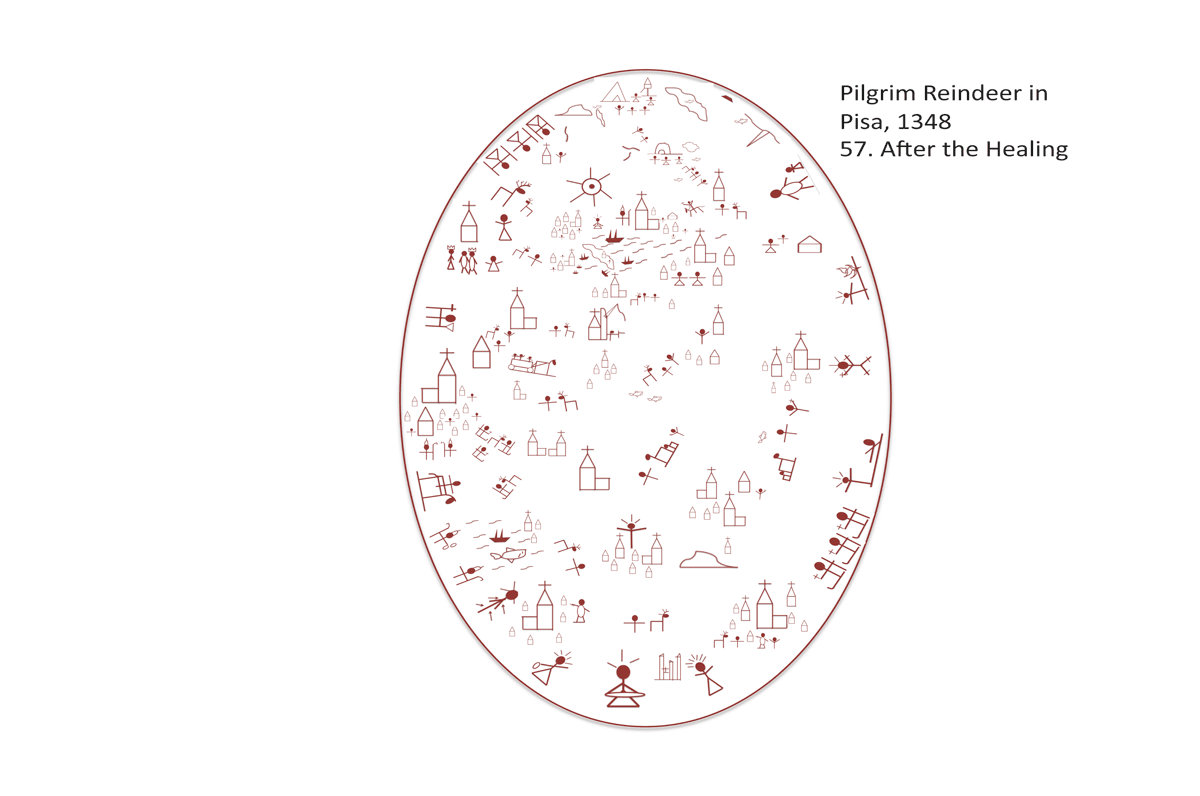

Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348

a free multimedia novel by

Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison

|

Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348 a free multimedia novel by Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison |

|

|

|

|

|

58. The Dark Night [July 26, 1349]

Where were you when I founded the earth? Tell me, if you have understanding.

For Bávlos, locked inside a tiny cell deep beneath the surface of the earth, days had turned into weeks and weeks into months. Every day was the same: meager rations, jeering taunts, kicks and bruises and spit in the face. Every now and then, Bávlos found himself hauled out, led shackled before a panel of magistrates who frowned at him and asked difficult questions. How had he cured the painter? Where had he learned such demonic tricks? Why had he chosen to cure Buonamico in particular? Was Buonamico not known as a lazy and self-indulgent wretch, the laughing stock of all the virtuous in the whole of Tuscany? Was he more valuable than the holy abbess of the convent here in the city, a woman of great learning and universal esteem? She had died along with most of her nuns the very week after Buonamico completed his painting of San Sebastiano for their church. Had not Bávlos accompanied the painter to that convent on the Feast of the Epiphany, the very eve of the arrival of the Plague in Pisa? How was it that Bávlos had advised Buonamico to flee the city even before other folk knew that the Plague was imminent? The questions were always so complicated, so barbed, like the quills of the slow and malicious beast that lived in the forests here: they penetrated to the bone and could not be pulled out. When Bávlos tried to think of a clever means of answering, these men would always resort to torture, and all of his well-laid plans would fall apart. He would say what they wanted to hear simply to make the pain go away. And they would sagely nod and scribble everything down in their books. It was all a hopeless muddle now, and Bávlos felt that he had said enough for them to be certain that he deserved to die. All of the questioning, and even the torture, would have been bearable to Bávlos, if they had been all that he faced. But spending day after day in that dark and stifling prison cell sapped the life out of his body and left him disconsolate and exhausted. He couldn’t bear the immobility of his state, caught like an animal in a snare, unable to escape, awaiting certain death.

He thought back to his former days in his father’s lands: of the woods and the rivers, of fish traps, and boat-making, of gathering golden luopmanat berries in the bogs and seeing his sister Elle smile. How many treasures he had enjoyed in those days! How distant they all seemed now in this dank pit of stone bereft of light or friendship. Worse still, Iesh no longer spoke. He no longer answered Bávlos’s calls, no matter how often or how pleadingly Bávlos called. Neither did his grandfather answer, or the Virgin, or any of the many voices that had once been so ready to talk to him. They were all silent, as if reproaching him for some terrible wrong he had committed, some transgression or insult that had driven them all far away.

“Why do you leave me so?” cried Bávlos in anguish. “What have I done to deserve such treatment?” His only reply was the silence of the night: hard and wordless and unbending. There was no comfort for Bávlos, no comfort at all.

Then one night a voice spoke at last. It was not like the voice of Bávlos’s grandfather, nor that of Francesco, nor that of the Virgin or Iesh. It was deep and powerful sounding and it spoke in a heavy accent that Bávlos did not recognize. “You and I, Bávlos,” said the voice reproachfully, “our horns are locked.”

“Locked my Lord?” said Bávlos, “Have I been vying with you?”

“You have,” said the voice simply and with finality. “You say that you are my servant, but you have always acted for yourself first, and you would tell me what to do.”

“I tell you?” spluttered Bávlos, incredulous. “When have I ever told you what to do?” What was this voice on about, he thought: had Bávlos not answered Iesh’s every command, leaving family and friends behind for the lonely trails of the pilgrim? Had he not sacrificed everything to heed the voice and come to Italy? Even as he thought these things, he began to fill with doubt. Was not Italy quite a nice place to come? Had he really suffered at all in this journey? Had he not been handed a fantastic adventure with no real demands at all? As the doubts rose, Bávlos tried to force them down. Gritting his teeth, he repeated himself defiantly, “When have I ever told you what to do?”

The voice made no answer. After a long while, in a tone half bitter, half a sigh it said: “And still you persist in ordering me to tell you what you want to know.”

“I am not ordering you,” said Bávlos, with a twinge of guilt. He knew he was lying even as he said it. He had been ordering Iesh to tell him the truth, to explain himself so that Bávlos could understand. “I’m sorry.” He said at last. “I understand what you mean, I guess. You’re not at my beck and call to answer my questions simply because I’m curious. But surely, you could tell me out of friendship’s sake.”

“Friendship’s sake,” snickered the voice. “You have been my friend have you?”

“Well yes,” said Bávlos, irritated at the laughter. “I’ve tried at any rate.” Beneath the surface he wondered why he had even bothered. Iesh didn’t seem so terribly worth the trouble all of the sudden.

“When it’s been convenient to you, yes,” said the voice dryly. “When it’s been to your advantage, you’ve been my friend. And I’ve rewarded it pretty richly, I think you’ll agree.”

Now it was Bávlos’s turn to remain silent. He saw in his mind’s eye all the joys and ease of his travels: the fishing with Pekka, the friendship with Jacques and with Buonamico and with Giovanni, the good food in France, the warm sunny days and wine of Italy. He felt wracked with guilt: he had been nothing but a spoiled and headstrong fool. The voice continued reproachingly: “My friends are those who do my bidding, even when it brings them nothing.”

“And did healing Buonamico earn me something?” asked Bávlos with a snort. “Am I enjoying riches from my feat?”

“Your feat,” said the voice with a laugh. Bávlos felt guilty again.

Still he persisted: “All right, yes, I know,” said Bávlos. “It was your feat. You cured Buonamico. But I helped. And did I receive anything for it, I’d like to know?”

“You did,” said the voice simply. “You did.”

“What did I receive?” asked Bávlos incredulously. “What on earth did I receive?”

“On earth indeed,” said the voice. “What on earth. Did you not earn the admiration of your friend Buonamico and your little follower Giovanni? Do they not look up to you like the Savior himself?”

Bávlos winced. He had felt pride at what he had done. He had been glad to prove at last to Buonamico once and for all that Sámi ways and knowledge were better, that he was better. It had been all about himself all along. Proving his worth. Proving that he was finer than any Italian or Frenchman or German or Jew or Swede or Finn. Better than any of the other Sámi back home. Better than his grandfather. Bávlos felt as if a curtain had been pulled aside to show him the truth of his nature. “I have failed you,” he said quietly. The voice made no answer.

“Now Nieiddash,” said the voice after some time, “Nieiddash did my bidding.”

“Nieiddash?” said Bávlos, grinding his teeth. “You call Nieiddash obedient? She who gave me the slip out in the forests of Sweden, taking up with a strange bull, forgetting our mission?”

“Forgetting your mission?” said the voice with what Bávlos felt sounded like a mocking tone. “Did Nieiddash forget your mission? She followed my command.”

“Your command?” said Bávlos desperately. “I can’t understand you.”

The voice seemed to relent at Bávlos’s pleading tone. “Tell me Bávlos, was it not the milk from Nieiddash that saved Buonamico and the infant in Siena? Could a reindeer cow give milk without a calf? How could you have accomplished your mission, as you put it, without Nieiddash’s help? Does it irritate you that I am more pleased with her than with you? After all, I saved not only the people of Ninevah but also their cattle.”

Bávlos slumped in his corner of the prison cell. The shackles on his arms seemed heavier than ever now. It had been horrible to be so questioned and goaded by the magistrates these many months. But now Iesh too was taking his turn at it, and he was the cruelest questioner of all. “Why, O Lord, why do you torment me so?” he said weakly.

“What if I do,” persisted the voice icily. “What if I am pleased to crush you in your infirmity? Is it not my right? Did I not allow worse to happen to Job?” The name made Bávlos think of juobmu, the green leafy plant that folk added to reindeer milk to give it flavor when stored away, the plant that Giovanni had gathered to add to the milk which had cured Buonamico. Oh how wonderful it would be to taste juobmu again, to see the green of a meadow back home and stretch out beneath the open sky and enjoy the long, warm sunshine of summer! Bávlos could see juobmu before him in the form of a slender girl, combing her hair and smiling.

“Hungry Sálle?” she said, half winking her sparkling eyes. “Hungry in your fine Tuscan lands? Are you pleased with what you’ve done?”

“Pleased with what I’ve done?” said Bávlos. “What is it I’ve done?”

“Oh now you’ve done nothing?” smiled the girl, pulling her long hair back off her neck and smiling broadly. “Just a moment ago you had followed the Master’s every command and saved Buore ustit singlehandedly.”

Bávlos felt guilty again. “Not again,” he said sighing. “Will you criticize me too?”

“Ah, poor Sálle,” said the girl, hardly taking notice of Bávlos’s pleas. “What a tough life he has with his friends in Italy, eating the finest foods, filling himself to bursting on fresh fish, avoiding the winter darkness. What a tough life you’ve had. And your family, do you feel no sorrow for having abandoned them so long ago? How are they to get by without you to work for them? But what does that matter to you,” she said, her voice trailing.

“What was I to do?” asked Bávlos. “Did I do wrong? Tell me so that I can understand!”

“Look at me, friend Sálle,” said the girl sitting up. “Does the juobmu take anything in return for her sacrifice? Does she not give of her very self to sweeten and preserve the milk that will sustain you? Does she not release her healing powers into the drink you take when ill? Does she ask for your praise? I pour myself out as a libation and you hardly take notice that I exist. But I do not mind: I do what the Master has commanded.”

“And I do not?” asked Bávlos.

“When it suits you,” said the girl, “when it suits you.” She faded from sight. Bávlos felt pangs of hunger. He wondered what it was like to drink milk, what it felt like to feel a breeze, what it sounded like to hear a pleasant word. He closely his eyes and tried to sleep.

Deep in the night Bávlos saw another young woman approach. She was soft and rounded, with warm eyes and long brown hair. “Bávlos,” she said, “Bávlos, wake up!”

“Elle?” said Bávlos, “Elle, is that you?”

“No,” said the woman. “Elle is back home. I am Nieiddash.”

“Nieiddash,” said Bávlos, his eyes tearing. “Nieiddash, thank you for coming.”

“Listen,” said the woman looking furtively over her shoulder. “I’ve been pleading for you, pleading for you. The Master is grouchy at times, but I think I’ve got him won over. It was terribly nice of you to make sure I got back to the Mountain. Admirabilis and I are doing well thanks to you.” All at once it struck Bávlos that perhaps this was the purpose for which he had been called: to escort Nieiddash and make use of her milk. How presumptuous he had been! Thinking the whole universe was centered on him.

“Nieiddash,” he said. “You are pleading for me—thank you my friend.”

“We are friends, you and I,” said Nieiddash. “And I wouldn’t have calved successfully without your wiry little arm! Don’t forget, that little brother! It was quite a help, though really rather distasteful.” Bávlos’s eyes widened. He had helped. He had helped Nieiddash survive. He had helped Admirabilis live. And that had made it possible for Nieiddash to make her milk, the milk that the Master had used to heal his favorites here in Italy.

“What am I to do?” said Bávlos desperately. “Tell me, sister Nieiddash, what should I do?”

“Submit,” said the woman pointedly, “Submit.”

“Submit?” said Bávlos perplexed. “What do you mean?”

“Submit.” said the woman simply. “Let the Master be in control, as I have done. Don’t order him around; he hates that. When you let go of your insistence on controlling everything, he will release you, I promise. Submit.”

“I will try,” said Bávlos. “It won’t be easy, but I’ll try.” As the night wore on, Bávlos felt a calm come upon him that was unlike anything he had every felt before. The calm of accepting all that was happening. The calm of letting go.