Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348

a free multimedia novel by

Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison

|

Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348 a free multimedia novel by Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison |

|

|

|

|

|

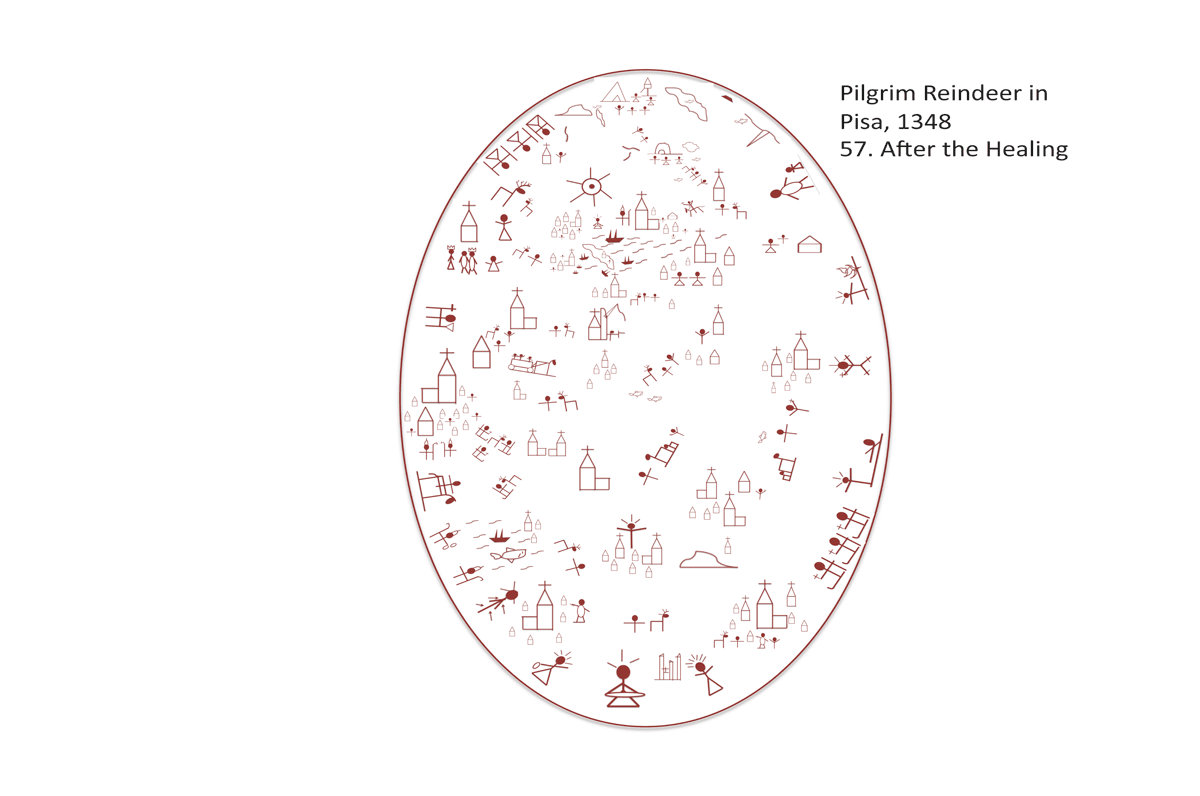

57. After the Healing [April 13, 1349]

A leper came to him and begged him and said, "If you wish, you can make me clean." Moved with pity, he stretched out his hand, touched him, and said to him, "I do will it, Be made clean." The leprosy left him immediately, and he was made clean. Then warning him sternly he dismissed him at once. He said to him "See that you tell no one anything but go, show yourself to the priest and offer for your cleansing what Moses prescribed; that will be proof for them." The man went away and began to publicize the whole matter. He sprea the report abroad so that it was impossible for Jesus to enter a town openly.

Looking back on the matter months later, Buonamico knew that he should have realized what might happen. Scores of people had died in the Plague: good people, healthy people, people of high repute. They had prayed and struggled and died. But he, a profligate, a spendthrift, an artist—he had had the audacity to survive. And to do so not simply by avoiding the disease: no, he had gotten it, and bad. He told everyone he knew all the details afterward: How his groin had been as purple as a king’s footstool, how he had lain in bed with a fever, untended by anyone. And then, out of nowhere, his friend the Fennus pilgrim turned up, bundled him in bandages, speaking in strange voices and feeding him concoctions in the forest. People had been filled with wonderment at the tale; but not the wonderment of joy. No, too many people had seen too many die to feel joy in the story of one wretched artist’s miraculous survival. Instead, they asked more questions, becoming more suspicious every moment. Who was this Fennus pilgrim? Where did he come from? When had he come? Why did his arrival seem to coincide so perfectly with the coming of the Plague?By the time Buonamico realized what he had started, it was too late. The Pisan authorities had been called in and they had found and arrested the pilgrim.

The trial against Bávlos proceeded deliberately and with purpose. In the crazed time of the Plague, accusations had flown far faster and with much less need for evidence. Jews had been locked in their homes and burned to death on the assumption that their very presence offended the Lord. Occasionally they were tortured into making confessions that they had brought the pestilence out of their hatred for the Christians. Gypsies had been chased down and murdered as they attempted to enter a town. Pilgrims and friars—formerly symbols of a living Christian spirituality—became the objects of mass violence. And how could it be otherwise? Neighbor no longer helped neighbor; doctors no longer responded to calls for help, even the pope in Avignon had sequestered himself away in his palace, refusing all visitors and burning protective fires at all hours. Trust and openness and charity were gone, victims of the terror of the Plague. It was in the aftermath of this disintegration of the very fabric of Christian society that the ecclesiastical authorities had begun their careful, lethal examination of the culpability of Bávlos the pilgrim.

Buonamico comforted himself only that he had managed to send Giovanni off with the reindeer to Mount Morello, where he set them free. That had been Bávlos’s last request of him, made in code as the guards listened in: “Ah, good friend, “ Bávlos had said, “Do me one favor. Bring old granny the milk maid and her grandson to the place where we dined that time on ham. How they would enjoy those forests again!” Buonamico had nodded, knowing exactly what he meant. He had done so just in time, for the authorities had soon arrived to impound the animals as evidence in the trial. They sent men out after Giovanni, but Giovanni, now schooled in the ways of overland trekking, stayed far out of their reach. He lived in hiding near the chapel of San Bartolomeo, receiving food and help from the holy monk that lived there.

Buonamico, both the cause and a chief piece of evidence for the trial, pleaded for his friend at every available occasion, but nothing he said seemed to help. In fact, his testimony often seemed to make matters worse. Stories about of a man who had tamed a deer and used him as a pack animal, of St. Fina preserving livestock unharmed in a public place, such details did not sit well with the church authorities in the aftermath of a pestilence that had wiped out half of the city’s population. They were looking for someone to blame, it seemed, and Bávlos was made for the purpose. Stories filtered in about other things this Bávlos had done: healing a dying child in Siena, speaking in strange tongues in Lucca, the list went on. And then Bávlos had made things worse himself, telling the bishop about his pagan upbringing far in the north and of the evil of taking soil from Golgotha.

None of the Franciscan friars that knew Bávlos were around to take his side: most of them were dead. They had served the sick tirelessly during the raging of the Plague and had succumbed themselves. Brother Mario, who had first told Bávlos about Francesco was dead, as was Brother Felix. Of the friars who knew Bávlos to any extent, only one remained, the young and callow Brother Giovanni. When he was eventually summoned from Florence, he told of Bávlos’s stigmata and of his walking back from Assisi to tend his dying friend. The authorities doubted the veracity of the stigmata, which had become mere scars. To prevent him from trying to inflict such marks upon himself again so as to win the public’s sympathy, they had chained Bávlos in a prison cell with his arms spread far apart. After months, when the scars remained as evident as before, their theory changed: now these were signs of former demonic possession. It was nearly a year later that the ecclesiastical authorities of Pisa were finally convinced beyond doubt that this wandering Fennus deserved punishment. And that punishment would be execution.

In his sorrow and frustration, Buonamico had contemplated leaving the city forever. But then he decided against it. No, he would stay and complete his fresco. He needed to work out his sorrow over the many deaths he had seen, and he needed to publish the realization he had received regarding the vanities of life. Finally, he needed to acknowledge the selfless help his friend had given him, if only in a small corner, if only in a cryptic image. On the last giornata of his work, far in an upper corner, he painted himself milking a reindeer.