Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348

a free multimedia novel by

Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison

|

Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348 a free multimedia novel by Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison |

|

|

|

|  |

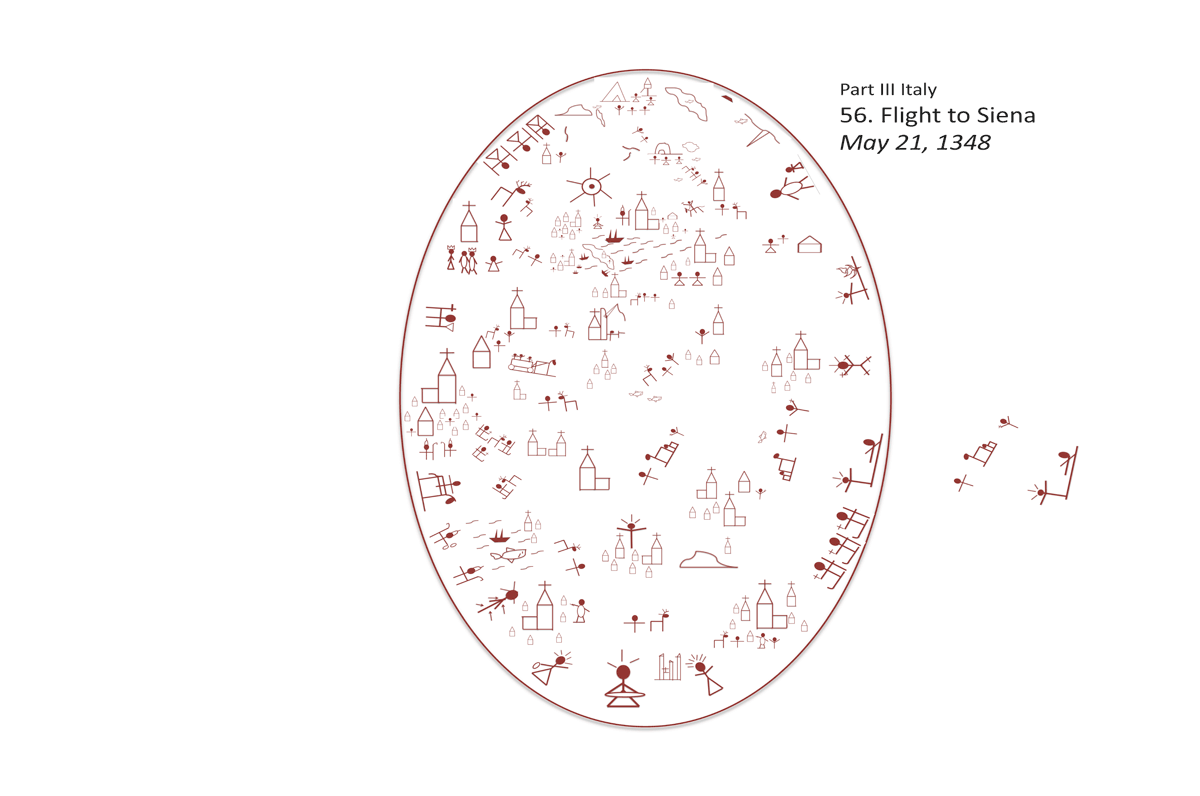

56. Flight to Siena [May 21, 1348]

So it will be at the coming of the Son of Man. Two men will be out in the field; one will be taken, and one will be left. Two women will be grinding at the mill; one will be taken, and one will be left. As it was in the days of Noah, so it will be in the days of the Son of Man; they were eating and drinking, marrying and giving in marriage up to the day that Noah entered the ar, and the flood came and destroyed them all. Similarly, as it was in the days of the Lot: they were eating, drinking, buying, selling, planting, building; on the day when Lot left Sodom, fire and brimstone rained from the sky to destroy them all. So it will be on the day the Son of Man is revealed.

By the time they were nearing Siena, it was clear that the Plague had already arrived. Bávlos was walking better now, his wounds having seemed to close. They still broke open at times, however, and the wound in his groin in particular hurt nearly ceaselessly. Others had opened as well: his chest and underarms felt especially sore, as if Bávlos had been carrying a great cross a long distance or had been flogged repeatedly in these areas. The friends were constantly meeting people who were fleeing toward the east, bringing news of the killing pestilence and shaking their heads in disbelief at the friends’ determination to proceed toward Siena.

Bávlos could not have made it this far without Giovanni. The younger man had taken up the tasks of hunting and fishing, tending to Nieiddash’s needs while Bávlos, wracked in pain, lay to rest at intervals on their way. It was on one night as the two men had settled in for night that Bávlos realized the urgency of the situation. High above in the southern sky he saw the demon Favtna, menacing and powerful. Back home, Favtna was never visible in the summer, because the sky never got dark enough to see the stars. Here, however, it was clear that Favtna was doing well, and that he had climbed higher in the sky than Bávlos had ever seen him do before. Gállá and his sons were nowhere to be seen. All at once, Bávlos saw a streaking light: a shooting star that crossed Favtna’s bow and sped directly toward the Sky Nail. It was an omen of the worst sort. Bávlos closed his eyes and began to sing the joik he had composed for Buonamico:

“Buore ustit, fat and crazy,

Loves his art and money too, lo, lo lo lo…”

As he sang, it seemed like he could see the painter before him, dabbing a wall and drinking from a flask. But now he was coughing, and bent over. He had toppled from his ladder and was stumbling toward the door, as if shot by an arrow. Buonamico was sick.

“We must get to Siena!” said Bávlos, “before it is too late!” The image of Buonamico actually in trouble seemed to push Bávlos’s pains aside. He no longer noticed his aching feet, and his hands felt nearly as good as new. His groin still hurt, especially if he shifted to the right at all. But this was no time for dwelling on pain, and Iesh had not given him these marks to make him useless at this most important moment. “When we get to Siena,” said Bávlos, planning as they walked, “You must stay in the forest with the reindeer. I will bring Buonamico out to us there.”

“If the painter is ill, shouldn’t he be in the safety and comfort of the city?” asked Giovanni hesitantly.

“No, that is the wrong way to heal,” said Bávlos firmly. “When someone is ill, you must take them away from everyone else. All sensible people know that.”

“Well, that’s the first I ever have heard of such a thing,” said Giovanni a little irritated, “What do you mean by ‘all sensible people’?”

“I’m sorry, my friend,” said Bávlos. “It was my Sámi side getting the better of me there. But listen, really, I need to bring Buonamico out of the city and when I do you are not to say his name.”

“Not say his name?!” cried Giovanni, “Bávlos, are you feeling well yourself?”

“And that’s another thing,” said Bávlos, “Don’t call me by my name when I come back with the painter and don’t worry that I don’t use your name either. Oh, and don’t be surprised if my voice sounds different. We have to fool this spirit if we are to get Buonamico free.”

“Spirit?” said Giovanni, “The Plague is a spirit?”

“All diseases are,” said Bávlos, “of that you can be sure.”

The days were warm and sunny as the friends made their way across the countryside now pushing themselves as fast as Bávlos in his state could go. Bávlos insisted on traveling across country and avoiding everyone on the road. “They could already be in the grasp of the spirit,” he explained. Giovanni simply nodded. He didn’t know what his friend meant, but he did know that Bávlos needed his help. And that was good enough for him. Bávlos still could not pull a bow with the wounds in his hands, and Giovanni was proud of the rabbits and fowl he had managed to shoot, as well as the fish. Mostly, though, they just ate the bread and cheese which Giovanni had taken from the priory’s larder along with a little milk from Nieiddash every evening. At last they came to where they could see city in the distance. They settled down to make camp.

“Tell me the joik that Francesco made of death”, said Bávlos.

“You mean in the Canticle?” asked Giovanni.“Yes, the Canticle. Sing me that part about Death.” Giovanni tossed back his head, closed his eyes, and sang:

“Be praised, my Lord in Sister Death,

there’s none who can escape her breath.

Bless’d he she finds in a state of grace

For Death will bring him to a better place.”

Bávlos felt soothed by Francesco’s words as well as Giovanni’s singing. Jápme, Death, was not something to be feared: she was a friend, a sister. The noaidit had always known her as such and her realm of the dead, Jápmeaimuo, was a place of contentness and rest. Provided one did what Iesh desired, Jápme’s coming would simply bring about the beginning of a beautiful eternity. Together Bávlos and Giovanni sang the last part of the Canticle:

“Praised and blessed may my Lord ever be,

Thanked and praised in all humility.”

As the afternoon drew to a close, Bávlos showed his friend some of the meadowgrass plant he knew as juopmu. It had a long spike of small pinkish red flowers and was easy to notice in the meadow where they sat.

“Gather leaves of this plant for me, can you?” he said. “Ah, l’acetosa,” said Giovanni nodding. “I will find you lots of that. Very bitter.”

“And also bark from this tree, its little branches, “ said Bávlos, pointing to a low-growing bush full of thin branches.

“We call it siethga, or at least we have something like it in my land that we call siethga.”

“Salice,” said Giovanni. “I can find lots of that down near the stream.”

“Good,” said Bávlos. “Cut it into little strips and soak them in my cup with some olive oil.” He handed Giovanni his wooden cup that he always had with him.

“I will do that,” said Giovanni. As it grew dark, Bávlos, readied himself for the trip into the city. Everything had to be done in just the right way: Buonamico’s life depended upon it. Bávlos did not pause to think about the fact that he was perhaps trying so hard to save his friend’s life because he thought that maybe his soul wasn’t quite in as great a state of grace as one might hope. Buonamico had his failings, but that wasn’t the issue. Iesh had called Bávlos to this land to save him and Iesh must have some reason for wanting Buonamico alive, even if Bávlos might have to die in the process.

As the night fell, Bávlos pulled his tunic’s hood over his head and hurried down to the city. As he approached, he found the city gates entirely unmanned. Inside, it was chaos. There were dead bodies lying by doorsteps. The stench of corpses hung in the air. Flies were swarming everywhere, and rodents scurried to and fro in the evening light. Bávlos made his way resolutely to the street near the priory where Buonamico had had his lodgings. He found the door unlocked. He pushed it open. Inside, in the dim moonlight that streamed through the bedroom window, Bávlos caught sight of a man lying in his bed. The covers were pulled tight around him and he was muttering to himself.

“Hello, old friend,” said Bávlos in a voice that sounded like a nanny goat.

“Ah! It’s Death come to take me!” quaked the man, pulling the covers over his head.

“Not Sister Death, no,” brayed Bávlos, “Just a friend come to see his thin little friend!”

“Who on earth?” Buonamico muttered. He raised his head as Bávlos momentarily removed his hood, placing his finger to his mouth.

“Ba-”

“That’s right, Baa, baa; it’s me, old nanny goat, come to take thin little Nino out for a stroll!”

“What on earth?! Ba-”

Again Bávlos hushed him before he could say his name. “Not my name, you nitwit, just play along! Where are the others?”

“All dead,” moaned Buonamico, the tears running down his cheeks. “The landlady on Tuesday, poor sweet little Angelo just yesterday. The brothers at the priory, all dead, all dying. People came and dragged out Angelo this morning.”

“We have to leave this place,” whispered Bávlos. “The soil of Pisa has brought its revenge to this land and it has spread this far. We must leave at once.”

“Leave? But my boy, can’t you see? I am sick! I am cold; I am crazed by the pain in my groin and armpits! I am not going anywhere!”

“Shut up, little Nino,” laughed Bávlos in a cackling voice like a chicken’s, “You’re going for a walk now, you silly little fool!” With that, he wound the bedsheet around his friend’s body and lifted him onto his back. The weight was astounding. Buonamico felt as heavy as a full grown bear. In the darkness, Bávlos could feel the scabs tearing on his feet. “Iesh, he said to himself, “I cannot do this alone.” It seemed like the load lightened at that moment. Slowly, painstakingly, Bávlos managed to make his way to the doorway with his human bundle. Buonamico had gone limp, seemingly resigning himself to his friend’s insane acts.

Once outside, Bávlos was able to lean against a wall for support as he slowly inched his way toward the house’s stable. Although there were many in the streets, no one seemed to take much notice of this smallish friar carrying a human bundle. Something told Bávlos that such sights had become entirely too common in the last few days.

In the stable, Bávlos found Buonamico’s mule ankle deep in manure and looking crazed. He looked like had not had food or water for several days. Bávlos swung Buonamico into his small cart and harnessed up the mule. He loaded the wagon with sheets from the house and grain and hay alongside the ailing painter. Then he began to lead the mule and cart out toward the city gates.

“Help me, friend Mule, and we will come to a better place.” The mule seemed to understand.

When they arrived in the forest, Bávlos set immediately to work. “Zachareo!” he called, “give the mule some water and grain!” Giovanni sprang to action. “Right away, Sebastiano!” Bávlos had to smile at the name. Bávlos began to tear the sheets he had brought into strips and to wind these around the painter’s bed sheet.

“Dá lahttu golbma,” he said soothingly. “Is it Fennus magic you’re fixing to work on me now?” babbled Buonamico, only half conscious.

“Far from it!” cawed Bávlos, now like a crow, “No Sámi around here! Just us crows!” Layer after layer of bandage Bávlos wound around the painter’s body, quietly whispering his words of healing, Dá lahttu golbma’: ‘here are three limbs.’ ” When he was done, he hurried to Nieiddash and began to milk.

“Old woman,” he said, “I need some milk for our little Nino. He is hungry after a day of play.” Nieiddash opened her eyes wide in a way that seemed to say she understood. Bávlos carefully held the shallow rounded milk cup that he had carved for milking beneath the reindeer’s udder as he gently milked her with his right hand. As soon as he was finished, Bávlos poured the milk into his wooden cup to mix it with the olive oil and siethga bark as well as the leaves of juopmu which Giovanni had dutifully gathered.

“Drink this, little Nino,” he cawed. Then he knelt down to pray.“Friend Zachareo,” he said, “please say a rosary for little Nino, so that he can rest from his play today.” Giovanni looked confused but shrugged his shoulders and began to pray. In the meantime, Bávlos began his own oration in Sámi.

“Hear me, silly spirit!” he said, returning to his goat voice. “Buonamico has given you the slip! I saw him sauntering over the mountain, I saw him skipping stones by the river, I saw him climbing in a boat and sailing far away! He was laughing, he was smiling. He had given you the slip! Yes I heard the fellow whispering, ‘Foolish spirit will follow Nino, little Nino in the forest who’s not worth the time of day!’ And now poor spirit sees that Nino, little Nino in the forest has strong goats and crows for friends and the drink of an old, old moose, full of wisdom, full of strength. No, the spirit cannot reach Nino, for Nino is in his swaddling clothes sleeping soundly after his milk. But Buonamico is escaping! Run and find him, foolish spirit! Leave us animals behind!”

Deep into the night Bávlos tended his friend in this fashion, watching over him, cackling and squawking and assuming different voices, muttering in Sámi and joiking songs of strength. By the middle of the night it seemed that the painter was breathing more easily, and was even sleeping calmly for a spell.

The next morning, Bávlos awoke beside his friend, still wrapped in his bandages. “Friend,” he heard the man whisper, “My throat is dry.”

“Little Nino!” said Bávlos quickly, “I will get you some milk.” Again he milked Nieiddash and mixed juobmo and siethga into the milk. Again he tipped the wooden vessel and raised Buonamico’s head so that he could swallow the drink.

“Friend,” said Buonamico. “I, I have to confess something to you. I used the gifts you gave me to make money for myself.”

“I gave you no gifts!” brayed Bávlos, now assuming a mule’s voice. “But even if I had, I wouldn’t mind if you passed them on to others.”

“Yes, but I used them to gain commissions, one even to the place you so feared.”

“I’m just a mule; I don’t fear anything!” brayed Bávlos. “But if I did, I’d still forgive you. I’d forgive you for it all!” He could see tears in Buonamico’s eyes. He leaned down close to him and winked. “Now get some more sleep, little Nino!”

As the day wore on, Buonamico seemed to be getting better, but that only complicated matters. He started to complain about needing to relieve himself. “Can’t unwrap you, little Nino,” said Bávlos in a woman’s voice, soft and caressing. “You must remain wrapped until the fourth day.”

“Four days!” cried Buonamico, “You’re crazy!”

“Tut, tut little Nino, just pee pee in your bed.” The sun warmed the hillside and in the daylight Bávlos and Giovanni dragged the cart into the open so that their friend could receive the light. Giovanni sang the Canticle:

“Be praised my Lord in all you’ve done

Especially in our brother Sun.

He brings us light when it is day,

Fair, shining, splendid, every ray,

With you in likeness one.”

Finally, on the morning of the fourth day, Bávlos breathed deep and said to Giovanni, “Today our brother will rise.” He kicked the cart where Buonamico lay and said in a commanding voice, “Lazaro, come out!” Buonamico, startled, sat up. He managed to scoot his legs to the ground and slowly, unsteadily, rose to his feet. Giovanni and Bávlos crossed themselves.

“Get these things off of me!” growled Buonamico, “They’re driving me crazy!”

“Right away, little Nino,” laughed Bávlos and Giovanni together. Bávlos felt his groin and hands. His pain too had passed.