Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348

a free multimedia novel by

Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison

|

Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348 a free multimedia novel by Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison |

|

|

|

|  |

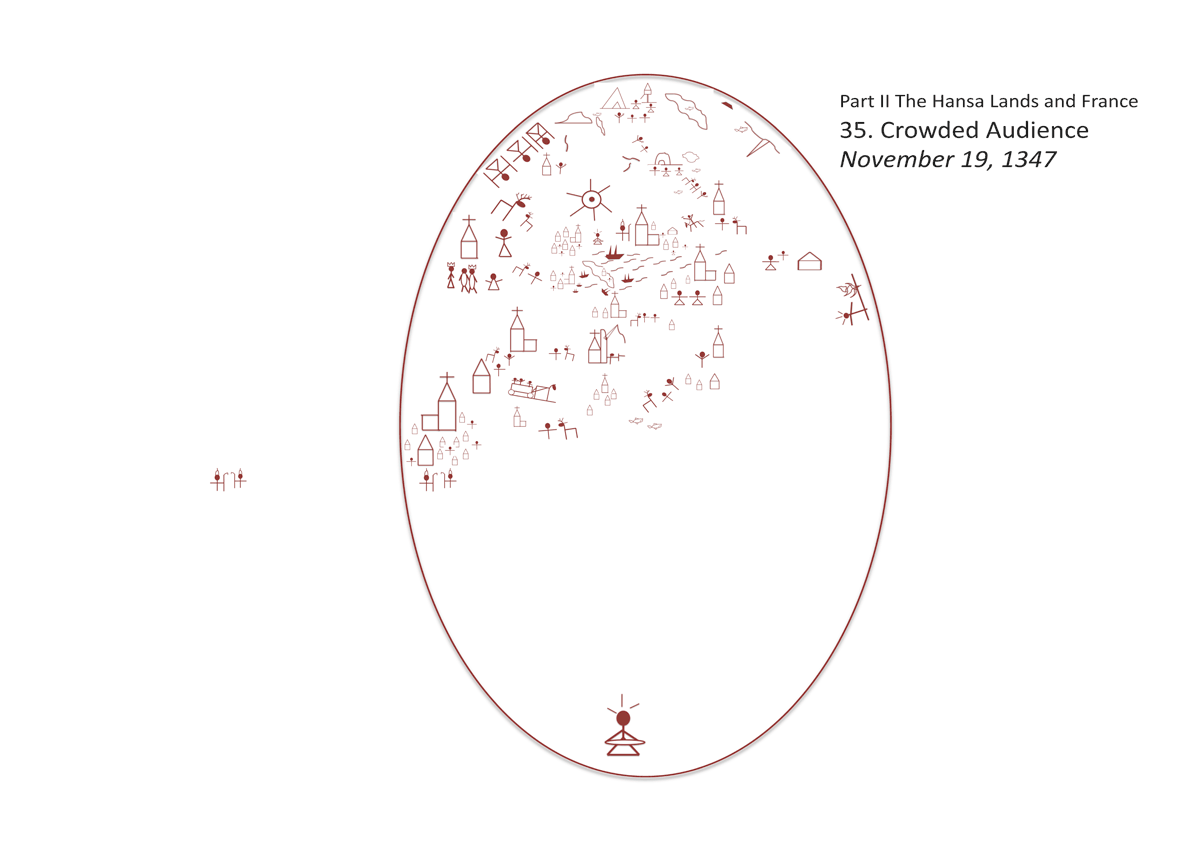

35. Crowded Audience (November 19, 1347)

We are both Jews and converts to Judaism, Cretans and Arabs, yet we hear them speaking in our own tongues of the might acts of God.

“Well!” said Bishop Hemming in Finnish, “What a surprise to see one of our subjects, Master Thomas from the shores of the Torne River! You seem to have become lost on your way, my boy.”

“The name is Master Bávlos,” corrected Bávlos firmly and in Swedish, “from the shores of Sállejohka.”

“Master Bávlos, yes of course!” said the thin man with a look of happiness. “He whom the holy Lady Birgitta dispatched to Avignon with a reindeer and a call for the Holy Father to call a holy year!”

Bávlos nodded and smiled, bowing slightly in the way he had learned in France.

“To Avignon?” said Bishop Hemming in surprise. “I have a hard time imagining that the holy Lady Birgitta would entrust any errand of importance to one such as this!” Bávlos felt that the bishop’s statement was rather unkind, although he could certainly see his point: Bávlos was a strange messenger in comparison with the bishop.

“And yet she did send him,” said Peter, quickly, “at our Lord’s command. I remember it distinctly. She had a vision of this man delivering his reindeer to the Holy Father.”

“Did she?” said Bishop Hemming, raising his eyebrows. “And would that explain, Master Bertold,” he said, switching again into Finnish to address Bávlos, “why you failed to heed my explicit instructions to return to your home and leave visions to those whom God has so designated?”

“My reindeer ran away,” said Bávlos in Swedish, “and I caught her with the help of the fine daughter of Lady Birgitta. And she took me to see her mother. And her mother took me to see the king and queen. And they each gave me letters and said that I should bring my reindeer to Avignon as a gift from each of them.” He thrust his letters forward.

“So it is through the help of our monarchs that you are here, then” said Bishop Hemming, coming to grips with the strange reality of the situation.

“It is through Christ!” said his companion Peter with great energy. “How else could a simple man such as this make it all this way but for the divine guidance of our Savior and his Mother?”

“Yes,” said Bishop Hemming musingly, “that does explain it. It is through our Lady Birgitta’s prayers that he has come.”

At this moment, Bishop Foulques cleared his throat loudly and spoke in French: “Dear friends, it is agreeable, no doubt, for you to discuss your travel experiences with each other in your land’s quaint northern tongue, and it is to a certain extent amusing for us to witness and listen to you converse. But I would suggest that our audience can proceed no further unless you consent to avail yourselves of one of the cultivated languages of civilized discussion developed for the purpose in our lands, the language of oïl, or that of oc, or of course the eternal Latin.”

These words seemed to jolt Master Peter in particular, and he immediately began to translate them into Swedish for Bishop Hemming. After listening to Master Peter’s quiet rendering of their host’s admonition, Bishop Hemming replied in somewhat broken French,

“We is sorry to the confusion. We is going to speak of the French language now.”

“Fine,” said Bishop Foulques, smiling.

“And you, Sir Pilgrim,” he said, turning to Bávlos, “You can follow our conversation in the language of oïl?”

“Certainly,” said Bávlos. “Thank you for asking.”

Bishop Foulques nodded genially.

“Excuse,” said Bishop Hemming, breaking in, “but his man no can of the French language! My Master Pierre here will translate to him inside the common tongue of our land.”

“I would think that unnecessary,” said Canon Girard, gently intervening. “I can assure you, your excellency, that I have already spent some hours conversing with Monseigneur Bávlos, and his capacity in French is quite up to the challenge of this audience.”

Master Peter and Bishop Hemming looked at each other, and Master Peter quietly translated the canon’s words into Swedish.

“I see,” said Bishop Hemming in surprise. “No doubt a miraculous assistance provided at the Lady Birgitta’s fervent behest,” he murmured in Swedish to Peter.

Peter nodded sagely and said no more.

“If you please, then, dear guests,” said Bishop Foulques. “I have anticipated the topic of your entreaties today as touching upon our good King Philippe’s regrettable, indeed tragic, altercation with his vassal Edward, king of England. To help clarify this situation, then, I have taken the liberty of inviting my nephew, Guillaume de Chanac, of the Benedictine house of Saint Martial de Limoges, now a professor at the university here in Paris. Master Guillaume shall recount for you the details of this most unfortunate conflict.”

At these words, a young man of great elegance and nobility entered the room, striding easily, in robes as rich as those of his uncle’s. He was perhaps ten years older than Bávlos, with dark penetrating eyes and an amused smile. He bowed cordially at Bishop Foulques and then at the various visitors, and then launched into a very eloquent and enlightening lecture on the dynastic conflict of the house of the Capetians and that of the Plantagenets.

“Good listeners,” he began. “I think the world can agree that there have been few kings of such grace and elegance and strength and acumen as our beloved monarch of old, King Philippe, fourth of that name, called by his people le Bel. He was a beautiful king, a king that all the world looked up to in every way. Of course, he had his small failings,” said the young man musingly, “but these were tiny in comparison with the great talents he brought to his rule. And of course, he was the anointed king of our land, the son of the great King Philippe the Bold of the grand house of Capet, himself a son of the illustrious King Louis, whom we venerate as a saint.”

Everyone nodded and crossed themselves at the mention of Saint Louis, although Bávlos thought Bishop Hemming looked somewhat impatient. Master Peter was quietly murmuring a translated version of the young professor’s lecture in Swedish for his companion.

“It befell, and it is tragic to tell, of course,” continued Guillaume, “that in the fullness of time, good king Philippe left this world and passed his crown to his able but headstrong son King Louis, tenth of that name, who ruled with power and vision, although he was cursed by a shrewish and unfaithful wife. This temptress had a daughter, Jeanne of Navarre, but, so given was her life to unfaithfulness and harlotry that she did not deign to honor the king with a male child. And when this Marguerite died, the king married again, and his queen bore him a little son, who ruled but five days as little King Jean.

“At this time, according to French custom, and specifically the celebrated and now much debated Salic Law, the throne passed not to a woman, King Louis’s daughter Jeanne, but to his brother, King Philippe V. But when Philippe died a mere six years later, the throne passed again to his brother Charles, who ruled for a mere five years before joining his illustrious ancestors in his heavenly reward.”

“Yes, we knows this history also in Sweden,” said Bishop Hemming, interrupting rather irritably. “It is what comes next that is the problem.”

“Yes, indeed, adroitly put,” said the professor. “No one in the world disputes the propriety and wisdom of the kings selected for our blessed country up to this point. But now began the conflict. For since none of these kings since Philippe le Bel had had any sons, and since none of them had any brothers left, the peers of our land were obliged to turn to the worthy brother of King Philippe le Bel, Sir Charles de Valois, whose son Philippe became our chosen king.

“A nephew!” scoffed Bishop Hemming. Both Bishop Foulques and Guillaume stared at him for a moment without saying a word. Then at last, the professor resumed his tale.

“Now it happened that Good King Philippe had one unworthy child, a wretched and demonic daughter named Isabelle. And in time, she brought forth a whelp of her own, the little King Edward of England.”

“The grandson of the king!” said Bishop Hemming vociferously.

“Descended thus through his mother,” said Guillaume firmly, “and thus in no way a claimant to the crown of France. Such, you see is the nature of the Salic Law.”

“It is an established fact of royal inheritance throughout the world that a grandson has greater entitlement to the throne than a mere nephew,” said Bishop Hemming in Swedish. Master Peter dutifully translated his companion’s words into French.

“Your king’s prattle about the Salic law and the assertion that royal title cannot descend through the female line is absurd, simply absurd,” the angry bishop added. Master Peter tried to rephrase the bishop’s words in a somewhat less confrontational manner, but their sting was not lessened as far as Bishop Foulques and Guillaume de Chanac were concerned.

“We do not regard our established laws and traditions as ‘absurd’,” said Guillaume. “They have served us well for many centuries, and we have every reason to believe that God continues to smile upon them.”

“Until now, Brother Bishop,” said Bishop Hemming. “For now Christ has spoken through the Lady Birgitta, as has his Mother the Blessed Virgin, and they is clear that your way is wrong!”

“Pray, explain what you mean,” said Bishop Foulques. “Master Peter, could you perhaps clarify what our dear brother Bishop Hemming means to say?”

“I can,” said Master Peter nervously, glancing at the disgruntled Bishop Hemming. “It is to tell your king of the Lady Birgitta’s vision that we have come.”

“Lady Birgitta?” asked the bishop. “And who is she?”

“Kinswoman to our lord King Magnus,” said Master Peter. “From one of the leading families of our realm. She has been blessed with divine visions for nearly the entirety of her life.”

“Divine,” said Guillaume interrupting, “or demonic? It is sometimes difficult to say.”

“The Lady Birgitta’s visions have been carefully examined by the commission appointed by the Archbishop of Uppsala, and they have been declared unmistakably divine,” said Master Peter respectfully.

“And who was on this commission?” said Bishop Foulques, nodding slightly.

“His excellency Hemming, archbishop of Uppsala, his excellency Hemming, archbishop of Åbo, Master Peter Olafsson, abbot of the monastery at Skänninge, and myself, Master Peter Olafsson of the monastery at Alvastra.”

“I see,” said Bishop Foulques, “no doubt a very worthy and studiously neutral body.”

“Indeed,” said Bishop Hemming. An uncomfortable pause ensued.

“In any case,” said Master Peter, clearing his throat, “The Lady Birgitta experienced a vision of our Lord Jesus Christ which stipulates both the rightful claimant in this royal conflict and a solution by which to end the unfortunate hostilities that plague both lands.”

“And what has Our Lord told the Lady Birgitta?” asked Bishop Foulques.

“Jesus notes that the grandson of King Philippe le Bel holds more right to the throne than the nephew.”

“I see,” said Bishop Foulques with a sniff.

“And so,” continued Master Peter quickly, “Our Lord kindly requests that King Philippe step down as king and cede the throne to the rightful heir.”

“Ah,” said the Bishop Foulques again.

“But in order to prevent future strains about this matter,” added Peter, “Christ urges a royal marriage that will reunite the son of Edward more fully with the line of King Philippe and ensure a peaceful and prosperous reign for the combined realm. The House of Capet will unite with the House of Plantagenet, and peace will rule our world until the end of time.”

“My goodness, how nice,” said Bishop Foulques. “How wonderful to have this message from our Lord dictated to an obscure noblewoman in a forgotten corner of the world.”

“Lady Birgitta no am obscure,” broke in Bishop Hemming, “and our country no is a forgotten place.”

“Yes, well,” said Bishop Foulques politely, “Did Christ have anything more to say via the noteworthy Lady Birgitta?”

“Yes,” said Master Peter eagerly, “A warning!”

“And the warning is?” said Bishop Foulques.Master Peter carefully unrolled the scroll he had been fingering for the entirety of the conversation and began to read. Bávlos surmised that he was translating the text from Latin:

“But if he who holds the realm does not comply, this will go ill for him. He will lose his life in pleas and be forced to leave his realm in difficult circumstances.”

“And by this, Our Lord means King Philippe or King Edward?” asked Guillaume.

“Why, of course, King Philippe,” said Master Peter, a little flustered.

“But both kings ‘hold a realm,’ do they not?” he asked.

“Yes,” said Master Peter, hesitating, “But I believe that Our Lord meant here—“

“Ah, so we are shifting to your beliefs now,” said Guillaume. “We have left the vision’s own text as too ambiguous too fully comprehend then, I take it?”

“No,” said Master Peter, “I know what the Lady Birgitta, I mean, I know what Our Lord intended with his words. It was I who rendered them in Latin from the Swedish of Lady Birgitta.”

“How convenient!” said Guillaume. “And the intent of Our Lord is always so crystal clear in prophecies, is it not?”

“I do not know what you mean,” said Peter, squinting.

“Well,” smiled Guillaume. “Of course the Apostles all understood all of Our Lord’s prophecies concerning his death when they first heard them.”

“No,” said Peter quietly, “I suppose they did not.”

“Ah yes,” said Guillaume, smiling, “thank you for that correction, Master Peter. Now that I think of it, it seems the Apostles understood few or little of the words Christ said to them until after his death and resurrection. Is that not so?”

“It is so,” said Master Peter tersely.

Bishop Foulques now interrupted. “Is my brother bishop familiar with the practice of the chevauchée,” he asked, barely containing his anger, “which this so-called rightful king Edward Plantagenet has inflicted upon his supposedly divinely ordained legacy? Lands burned, farms pillaged and destroyed, women raped and killed? All to provoke battle and to bring shame to King Philippe. Perhaps my brother can explain the holy purpose of such practices, which have ravaged many parts of the west and north of our land? It is familiar to you, my friend?”

Bishop Hemming remained impassive. “What did he say?” he murmured to Master Peter. The speed and restrained anger of the other bishop’s words had taken him by surprise and he did not seem to have understood anything.

“He describes some brutalities of King Edward’s troops,” said Master Peter.

“Ah, yes,” said Bishop Hemming quickly, “Our Lady Birgitta, she revelation speak high angry on these things. Master Peter,” he said, switching into Swedish. “Translate for me: the Lady Birgitta’s revelation criticizes the rightful king for his excesses of arrogance and rage. His actions harm the poor. They fall like snowflakes to the flames of hell. The Holy Virgin Mother says this too.”

Master Peter assiduously rendered the bishop’s words in French. Bishop Foulques seemed somewhat mollified.

“But then,” continued Bishop Hemming, continuing in French himself: “King Philippe hurt the poor as well! If he just do reasonable thing, step down as king—“

“So Our Lord and the Blessed Virgin, we are to believe, condone King Edward’s cruelty because he holds the rightful title to the throne according to English practice?” said Guillaume.

Master Peter intervened: “The Lord Jesus, speaking through the holy Lady Birgitta, says that both kings love peace,” he said with firmness. “But they both love justice as well. And sometimes the pursuit of justice entails unfortunate actions. King Edward has a burning desire to—“

“To burn?” said Bishop Foulques. “And rape? And pillage?”

Bishop Hemming pursed his lips and made no answer. He had understood these words rightly enough. “Hopelessly political, this bishop,” he murmured in Swedish.

“What did he say?” whispered the canon to Bávlos.“He said that your bishop is hopelessly political.”

“Ah,” said the canon, frowning. Then suddenly, the canon addressed the entire room:

“Your Excellency Bishop Foulques,” he said, “and good Master Guillaume, and your Excellency Bishop Hemming, and good Abbot Peter of the order of the Cistercians, pray, let us ask our other ambassade what he thinks of this regrettable situation.”

Bishop Foulques smiled. “Indeed,” said he, “please tell us, Sir Pilgrim, your thoughts on this conflict. Who would be the rightful heir in your land?”

Bávlos thought for some moments, while all eyes rested on him. As last he said, turning to Canon Girard,

“Answer me this: was the Beautiful Philippe the older or younger brother of the younger King Philippe’s father?”

“Philippe le Bel was the older brother of Charles,” said the canon.

“Among our people we have a saying about Charles: he was the son of a king, the brother of a king, the uncle of three kings, and now the father of a king, but never a king himself.”

“Ah,” said Bávlos. “That is significant. And this Edward, am I right in understanding that he is the grandson of Beautiful Philippe through his mother rather than through his father?”

“Yes,” said Guillaume, “It is through his mother, the wretched Isabelle.”

“I see,” said Bávlos, clearing his throat and speaking deliberately so that even Bishop Hemming might understand: “Then in my land, the favored person would be Philippe.”

Bishop Hemming gasped in anger. “In your land? “ he sputtered in Swedish. “What land is your land? Your lands belong to our king!”

“If you please,” said Bishop Foulques in French. “I would like to hear what else Master Bávlos the Pilgrim has to say.”

Bishop Hemming grumbled loudly and folded his hands. Bávlos continued his speech:“In my country,” he said, “it matters that Beautiful Philippe was the young Philippe’s eahki, and one’s eahki has great responsibilities that cannot be mistaken or forgotten. My eahki for instance fitted me out with the reindeer I have brought with me and all of the furs I took along on this trip and a great deal of other equipment as well. Now if Beautiful Philippe had been the young Philippe’s cheahtsi—his father’s younger brother—well, it wouldn’t matter so much. It would be okay to give him the throne, perhaps, but not a necessity.”

“One’s uncle is important in your land,” said Bishop Foulques, smiling.

“One’s father’s older brother is important, yes indeed,” said Bávlos. He continued: “Also, it must be said that this Charles, the younger brother of Beautiful Philippe sounds a little pathetic—the only one in the family who has not gotten a turn at being king! So by rights, Beautiful Philippe should try to do something nice for Charles’s son so as to make it up to him. These responsibilities live on even after the people are dead, which of course is the case with Beautiful Philippe.”

“And in your land Edward would have no claim to the throne?” asked Guillaume, glancing with amusement at the fuming Bishop Hemming.

“Well,” said Bávlos, “Not really. Beautiful Philippe is his áddjá, and that is a lovely thing. My áddjá was a great man, and I was named after him originally. He helps me in important ways too, but more in spiritual ways than worldly. It was my eahki who gave me my reindeer, for instance, not my áddjá.”

“I see,” said the canon approvingly.

“You see,” continued Bávlos, “when a girl marries in my land, she usually moves to her husband’s lands and then she becomes part of that family. So her son has rights in the woman’s new family, but not in her old. She brings her reindeer and other possessions along in the marriage, and then her children can inherit them along with everything they inherit from their father. But you see, they don’t have a right to the reindeer that were left behind at the girl’s old lands. This Isabelle and her son Edward are really part of another family at this point, although of course, it is important to stay friendly whenever possible.”

“It is fascinating how clear this logic is the world over,” said Bishop Foulques exultantly. “Even in the distant tracts of the far north, folk can understand these facts.”

“Brother Bishop Foulques,” Bishop Hemming began stiffly. He had not followed everything that Bávlos had said, but he had seemed to catch the drift. Now he spoke with restraint and deliberation in Swedish, while Master Peter translated into French.

“We have come to you today to ask your assistance in approaching your king regarding a message that has been sent by Christ and by Mary for the good of your country. Will you help us gain audience with King Philippe?”

“I shall not,” said Bishop Foulques, nodding serenely at his brother bishop as he listened to Master Peter’s words. “In my opinion, your testimony is written in the blood of innocent men and women, paid for by the greasy coins of Hansa merchants and their stooges.”

Master Peter translated this reply hurriedly, his eyes darting between the tight-lipped but clearly furious visages of the two bishops.

“I see,” said Bishop Hemming coldly in French. “Your political opinions is more the important than the truth of our Savior.”

“That is how you regard the matter,” said Bishop Foulques, “but I know what is in my heart.”

Master Peter translated these words, but Bishop Hemming had seemed to understand them himself.

“And then,” said Bishop Hemming in Swedish, “will you at least help us gain access to the Pope?” Master Peter translated the question, wincing a little as he spoke.

“The road to Avignon lies open to you,” said the prelate smiling. “By all means, present your entreaties to the Holy Father. He shall no doubt find them very revealing indeed.” Master Peter sighed deeply as he translated.

“We take our leave, then,” said Bishop Hemming turning toward the door. “Master Peter,” he said in Swedish, “Let us go. Oh, and Master Johan,” he said over his shoulder, glaring at Bávlos, “Do not ask our assistance in returning to your wretched northern home.”