Part II. The Hansa Lands and France

Chapter 35. Crowded Audience [November 19, 1347]

Cultural Explanations

|

Part II. The Hansa Lands and France Chapter 35. Crowded Audience [November 19, 1347] Cultural Explanations |

|

|

In this chapter Bávlos joins in the debate regarding the rightful heir to the throne of France. | ||

| Bishop Foulques, Bishop Hemming |

In this chapter, Bávlos hears the debate regarding the rightful heir to the throne of France. All of the details in this chapter, apart from Bávlos's presence and speech, are based on facts.

Bishop Foulques asks for his guests to speak in Latin, or the language of oïl, or the language of oc. The language of oïl was the language that we know today as French—i.e., the Romance language of the north of France. Its word for "yes" was oïl, modern French oui. The language of oc was the language of the south of France, "occitan," in which the word for "yes" was oc. In the early fourteenth century, both these languages vied for superiority. The language of oïl had Paris and other northern cities on its side; the language of oc had Avignon and a host of artistic and poetic traditions on its side. Guillaume and Foulques came from a south French family, and they spoke both languages fluently, as did most French clerics and aristocrats of the era.

It is important to recall that Bishop Foulques had received his post as a gift from his uncle Bishop Guillaume de Chanac. As this chapter shows, Bishop Foulques in turn showed much favoritism to his own nephew Guillaume de Chanac (1320-83). Guillaume was a rising star in the French church at this time. Just 27 years old, he had already been named (through his uncle's offices) a professor of theology at the Sorbonne. He was a Benedictine monk at the monastery of Saint Martial in Limoges. In 1351, soon after the events of this novel, Pope Clement VI (Pierre Roger) made him an important official in the papal administration at Avignon. He would later serve as Bishop of Chartres and of Mende. Pope Gregory XI (Pierre Roger's nephew Pierre Roger de Beaufort) made him a cardinal in 1371. When Gregory decided to return the papacy to Rome in 1377, Guillaume remained behind in Avignon.

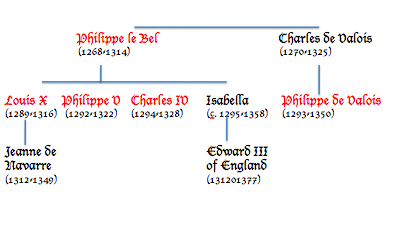

Nepotism—from the Italian nipote "nephew/niece/grandchild"—was a common part of ecclesiastical life in medieval France and Italy. Since marriage was forbidden to clerics, powerful bishops, cardinals and popes angled to pass on their wealth and status to nephews. Some historians have conjectured that some such "nephews" were really illegitimate sons, but in any case, the desire to pass on one's position to a family member proved far stronger than the theology of clerical chastity. The English pretenders to the throne never fully understood why their criticisms of uncle-nephew succession seemed to fall on deaf ears among the clergy and aristocracy of France. They regarded the French succession decisions as transparent moves to block the right of the English king to an obvious inheritance. Birgitta's vision supported the English view. Here is a family tree that may help clarify the issues:

|

| Genealogy of French heirs to the throne. All figures in red held the title of King of France for some time before dying. |

When the son of King Philippe le Bel, King Louis X, died without a living male heir, the French elected to turn the throne over to his younger brother Philippe rather than pass it on to his daughter Jeanne. When Philippe died, the throne passed again to his younger brother Charles. When Charles died (an unlucky family...) the French passed the throne to Philippe le Bel's nephew Philippe de Valois, rather than letting the line pass through either of the female heirs Jeanne de Navarre or Isabella de France. Bávlos sees this move as justified; the English did not. Nor did St. Birgitta, whose letter and vision Bishop Hemming and Prior Peter had come to share with the French. It is also worth noting that Edward III of England did not have much interest in the throne until arrival in the English court of Robert d'Artois, Queen Blanche's uncle, who had fled to England after being found guilty of forgery. Robert incited Edward to seize the throne, compelling him to swear to take it before the end of one year. So the Swedish royal family was implicated in this dispute in an important—though indirect—way, and this fact may have lessened the willingness of the French to take their Swedish emissaries very seriously.

Birgitta's vision is accurately summarized in this chapter. She experienced a vision of Christ in which he assured her that Edward had a greater claim to the throne and urged Philippe to step down. The idea of a marriage between the two families was also part of the vision, as well as the obscure line about the one who holds a throne suffering punishment. Whether that line referred to Edward or Philippe was not clear at the time and remained a sticking point in French and English interpretations of the vision for long after. Peter's remark about having written the vision down in Latin is also accurate: Birgitta dictated her visions in Swedish, and these were then translated into Latin and checked for theologically soundness by her confessors. In the fourteenth century, it was easy to fall athwart of the Church's definition of orthodoxy, and even high clerics were sometimes reticent to make theological statements without first checking their appropriateness with colleagues and allies. A lay woman naturally relied on her confessors for this sort of help, even when she regarded her visions as coming directly from the mouth of Christ or his Mother.

While issues of succession and theology were important features in the vitriolic debate concerning the rightful heir to the throne of France, Bishop Foulques's remarks about chevauchée were also of great importance. Chevauchée was a kind of medieval total warfare, in which an invading army destroyed all property and life in order to provoke the ruling king into battle. From the perspective of French townsmen and peasants, this tactic was regarded as a ruthless and bloodthirsty act, and it inspired little admiration for the ambitious English pretender. As with the ruthless tactics of the Battle of Crécy, chevauchée was one of the practices that labelled the English as the destroyers of the age of chivalry.

Bishop Foulques refers to Edward III as King Philippe's vassal because the duchy of Guyenne (Aquitaine) was a French duchy that Edward held at the behest of the French crown. The French frequently reminded the English of this fact, depicting Edward not only as a usurper but as a vassal who refused to show the French king the respect and allegiance he owed him.

The kinship terms that Bávlos cites are in northern Sámi. Eahki is father's older brother, while cheahtsi is a father's younger brother. Áddjá is the term for grandfather on either the father's or mother's side.