Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348

a free multimedia novel by

Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison

|

Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348 a free multimedia novel by Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison |

|

|

|

|  |

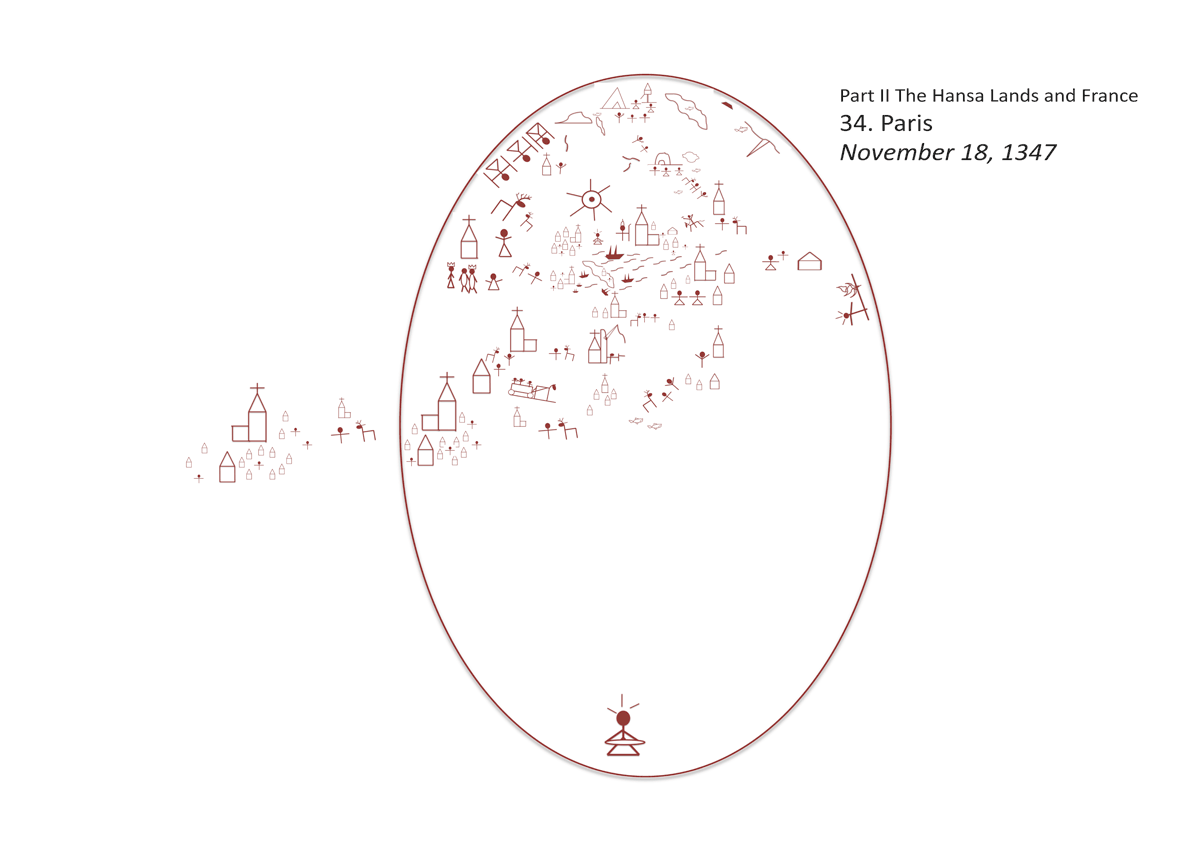

34. Paris (November 18, 1347)

Now Nineveh was an enormously large city; it took three days to go through it.

Bávlos followed the advice he had received from Jacques’ brother and soon reached Châlons. This was a great city, with many churches and monasteries and convents, and a great host of folk busily employed weaving cloth and tanning hides. Here Bávlos found the River Marne, which he duly followed west through the smooth undulating landscape of the region. The river supplied Bávlos with fish, which was a welcome source of food, particularly since Jacques and his lively singing were no longer along to bring in income. Bávlos thought it strange how quickly he had grown accustomed to earning money and how easily he had forgotten the normal way to live on the land while traveling. It felt good to be doing things in the old way again, independent of the whims of folk and their desire to prod Nieiddash or gape at his clothes.

As he followed the River Marne, Bávlos found that nearly every passer by was headed toward Paris, and those walking, boating, or riding in the opposite direction were nearly always returning from a visit there. Paris was like a great hive, to which all were busily headed, or the place upstream that spawning fish needed so desperately to reach. There was no need for asking directions on the way there, nor was it hard to find one’s way once the great city came in sight.

Bávlos entered the city by a gate close to the river on its southern bank, where he was obliged to pay a duty for himself and Nieiddash. Inside the city, Bávlos was amazed at the maze of great houses and streets that spread out in every direction. He followed a road that led toward the river until he came to a bridge that led nortward over a part of the river onto an island. That island, folk informed him, was the very heart of the city: the great isle upon which he would find the Cathedral of Nostre Dame as well as the king’s court. It was there Bávlos must go if he wished to find the queen’s friend Canon Girard.

The bridge leading to the island was itself lined by houses and hardly seemed like a bridge at all to Bávlos. What’s more, there was a toll station here as well, demanding more money of any who wished to cross. Bávlos humbly lined up with the other peasants of lesser degree to pay his toll. But when it came his turn, a dispute arose. It was easy to assess the fee for Bávlos, a foreign pilgrim, but how much should one charge for a reindeer? Apparently, this was not a common occurrence even in a city of such grandeur and importance. At first, the toll guard wished to assess the same fee as for a horse, but one of the other peasants in line retorted that Nieiddash, with her great antlers, was more like a billy goat, and thus, by ancient usage, exempt from tolls when crossing the Small Bridge, which, apparently, this great bridge itself was called.

“But it is nothing like a billy goat!” scoffed the toll official, waving his hand as if to dismiss the matter entirely.

“It is the horns that make a goat what he is!” cried another passer-by. Bávlos was surprised by the vehemence and enthusiasm by which ordinary folk were taking his side—it seemed a matter of great importance to everyone in the street.

“I could accept that description,” said the guard, relenting somewhat, “if the beast is to be slaughtered upon the island. Is that your intention, Sir Pilgrim?”

“No,” said Bávlos, somewhat helplessly, “I must keep her with me.”

“She is part of your craft?” asked an elderly woman who had stopped to join the discussion. “You use her to earn your living?”

“Well,” said Bávlos, recalling his time with Jacques, “yes, in a way—I used her to earn coins in my work as a jongleur.”

“Ah,” said another man, shaking his finger at the guard, “then the beast is like a jongleur’s monkey, and according to the fees established for the Small Bridge, must be allowed to pass for free.”

“Only if the jongleur agrees to perform a small entertainment for the benefit of the guard!” retorted the guard with dignity. “I am entitled to such entertainment when a jongleur passes with a monkey.”

“But the beast is not a monkey,” protested another man, “he is only like a monkey in that he belongs to this man’s stock-in-trade.”

“Nonetheless,” said the guard with finality, “I shall have my entertainment or the beast shall be charged as a horse or ox.”

Bávlos was perplexed by this entire discussion. He had no idea what a monkey was, nor did he understand who had come up with all these rules about fees for crossing a bridge. Nonetheless, if the guard wanted a song, he could certainly oblige. He recalled one of the ditties that Jacques had liked to perform when first attracting a crowd and carried it off quite well, incorporating Nieiddash into his routine as a kind of dancing partner. People applauded riotously and threw coins toward him, which Bávlos gratefully received and piled into his doffed hat. He was glad he had not chosen to joik: the response would probably not have proved so positive.

Upon crossing the Small Bridge, Bávlos found his way easily to the great Cathedral of Nostre Dame. Bávlos felt a sense of exhilaration as he gazed up at the magnificent building, deep grey against the chalky white of the sky: it was a crisp November day, and the air at last smelled like it could yield snow, a thing which this strange land seemed to have in only short supply.

The great cathedral itself was stupefying to behold: its towering arches and magnificent sculptures thrust upward into the sky to such a height that Bávlos could barely imagine how anyone could have built them but Iesh himself. His mind boggled to think that only three months earlier he had found the church at Hattula impressively grand. How serene, how heavenly this mansion of Our Lady was! How much more complete and at ease than the massive project of Master Gerhard in Köln. Bávlos felt close to the Virgin in this place, as if it were really her and not just a stone likeness of her standard far above on the great wall of the church, staring down at him with her welcoming smile, her son in her arms and winged spirit helpers on the right and left. She seemed to take little notice of these, but gazed at her son, and from time to time at Bávlos.

The houses of the canons of the cathedral were not as easily found or sorted through as the cathedral itself. They lay in a maze to the side and behind the cathedral: great houses of every sort and shape, crammed together, vying for attention. Locals laughed when Bávlos asked for the house of the canon of the cathedral, for there were fifty-one such canons and 120 chaplains, all employed every day in singing various masses at various chapels along the sides of the great cathedral. Their voices launched high into the grand spaces of the church and soared upward, echoing in a way that made Bávlos remember cliffsides in the mountains near home, where he would go sometimes to greet the summer sun. The high altar and chair of the cathedral’s finer end belonged to the bishop and he apparently did not want anyone else to sit in it, for it was well protected from the common folk by the rood screen and various other gates and devices. Bávlos could see another great box high up on the altar, covered with gems and silver and gold like the reliquary at Köln for the three kings, or the resting place of Charlemagne at Aix. Here lay a St. Marcel, a holy priest whom pagans had killed many centuries before.

It took much asking to find the home of Canon Girard. There were several of the name, and Bávlos had forgotten any more details of him except that he was the childhood friend of the gracious queen of Sweden, Blanche of Namur. At hearing Blanche’s name, folk seemed to know which Girard was intended, and they directed Bávlos eventually to his home, a large house behind the cathedral, but not the largest in the neighborhood by any means. Bávlos found an entry to the back of the great house, where he was able to stable Nieiddash and gain entrance to the house as a pilgrim guest. He showed the servants the two letters he had brought from the king and queen of Sweden, and they politely ushered him into a large room with a table and chairs. Before long, a kindly looking man of perhaps thirty entered, clothed in a white robe.

“Good day, monseigneur the pilgrim,” said the man. “I am Girard, a canon of the cathedral of Nostre Dame by the grace of our holy Lord Jesus Christ. How can I be of service to you?”

“Well,” said Bávlos, surprised by the canon’s pleasant and polite ways, “I have a letter for you from the queen of my country, Blanche of Namur.”

“Blanche,” said the canon smiling. “We were childhood friends! My uncle was her father’s confessor at his estate in Namur.” He took the letter and read it, glancing from time to time at Bávlos. “Yes,” he said at last. “You have a name to remind me of, a remembrance of my youth?”

“Gigi,” said Bávlos happily. He had remembered the name for two months now, and he felt a wave of relief at speaking it out loud. Now he would not be put to death, as Simon had warned.

“Indeed,” laughed the canon merrily. “I have not heard that name for many a year. I am so formal here, my life so dignified. It is pleasant to remember the happy days of my youth at your dear queen’s estate. You have a reindeer with you?”

“I do!” said Bávlos happily. “Let us go to see her!” laughed the canon. “Your visit brings me great cheer!”

Bávlos and the canon had a pleasant lunch in the large and warm dining room of the canon’s grand house. The canon seemed so happy to meet Bávlos, so full of vigor and curiosity. “You must tell me everything of your land in the far north!” he said. “I have the feeling that you are one of the people that the great bishop Saxo writes of, who course across the winter snow on planks of polished wood!”

“Ah, sabet,” said Bávlos. “Do folk not use such devices here? It seems like all things are to be found in this land.”

“Many things, yes,” said the canon. “But folk in these parts have never come up with a good way of traveling over snow. Generally they wade through it, and the snow trickles down their hose and into their shoes. And if they are not careful, their toes are frozen before their travel is done!”

“Do they not know about shoe grass?” asked Bávlos in surprise. “You stuff it in the shoes and then the snow can not get in. Can it be that these things are not known in this great land?”

“There is much that is not known here,” said the canon smiling, “though sometimes I fear we have learned too much.”

“Too much?” asked Bávlos. “Of war, and cruelty, and injustice, yes,” said the canon sadly, “of these we have learned much of late.”

“Ah, the war,” said Bávlos quietly. “Please sir canon, can you tell me why this war has come about between your land and the western isle of England? They say the two kings are arguing about who should have the throne of France.”

“That is what they say,” said the canon quietly. “But—”

“Is it not true?” asked Bávlos.

“The issue of who is rightly king is merely a pretext,” he said.

“A pretext?” asked Bávlos, “I do not know the word.”

“A pretext, friend pilgrim,” he said. “Do you not know how, when kings have mighty conflicts seething about one thing, they often choose to fight about something entirely different?”

“Do they?” said Bávlos. In this respect, these kings sounded very much like some Sámi relatives he could think of. “We call that dahkuágga.”

“Indeed?” chuckled the canon. “You must tell me more of your people; they sound quite fascinating.” Bávlos smiled.

“What was the real cause of the conflict then?”

“It is a struggle between two ways,” said the canon, “that have led to two camps: those who follow England and those that follow France. In the English camp are all the Hansa lands, with their bustling cities and many products: the wool merchants of England, the weavers of Flanders—”

“The makers of sculptures at Lübeck,” said Bávlos.

“Exactly!” said the canon. “All these cities filled men and boys and even women, laboring through the day to make objects that can be bought and sold. No one on the land anymore, tilling the soil like the decent folk of France!”

“Ah,” said Bávlos. He thought of the many villages and farms he had passed here in France, and how different it looked from the tracts between Lübeck and Köln.

“God has punished their choice by turning their summers cold, so that their lands can no longer yield the wealth of meat and produce and wine that we continue to enjoy in our blessed land. And so they have no choice now but to continue making and selling, buying and trading, forgetting the holy pact with the seasons and the land that God intended for all men.”

“But here men have not made this choice?” asked Bávlos.

“Some men yes,” said the canon judiciously, “but far fewer than in the north. Here, for the most part, both peasant and lord live upon the land and produce fine things that we may eat. These English and their supporters would mob our land and take it for their own, so that they can have our food. They would swallow France as they have swallowed the land of Guyenne in the south, to which the King of England holds claim. They would gnaw the meat from the fat flanks of this land and leave us to become merchants like them.”

“Ah,” said Bávlos quietly, “the death of chevalerie.”

“Precisely!” said the canon. “My son, I believe you understand things well.”

Later that afternoon, Canon Girard arranged to accompany Bávlos to the palace of the bishop. It was snowing heavily now, and the sky was white and silent. Bávlos realized suddenly how much he had missed the snow and the return of the winter season. For Sámi the return of the snows was not a time of sadness, as among these farmers, provided one had warm enough clothes and a place to hunt and trap. Tracking was easier in this season, and travel far swifter. Bávlos decided that he would need to make himself some skis right away and a sledge for Nieddash to pull. Then they would make far swifter time.

Canon Girard seemed on good terms with the bishop of this city, for when his name was announced to the prelate by a servant, the bishop sent word at once that they would be received. Bávlos was very nervous about having to face another bishop: Bishop Hemming had seemed quite enough for him. Still, he thought, what would the likelihood be that this Bishop Foulques would be as strange and as irritable as the holy Bishop Hemming? The latter was far away now, and Bávlos was in a new and gracious land, where people conversed in pleasant tones and did not tell him that he was a fool. This bishop Foulques, Canon Girard explained, was the nephew of the former bishop, Guillaume de Chanac, a great prelate from a noble family from the Land of Oc. He had ruled as bishop here in Paris for ten years, but then had been made the Patriarch of Alexandria and traveled far away. But he had left his nephew in charge, and his nephew had done a fine job since then.

Bávlos and the canon were escorted into a large, rather drafty room, where a large bishop’s chair stood. The servants were stoking a roaring fire in the great stone fireplace that stood across from the chair. Bávlos was surprised how little heat it seemed to provide: the high ceiling and cold stone of the room seemed to suck all warmth away, leaving instead a cold and drafty feel. The area near the bishop’s chair was richly hung with beautiful tapestries, depicting scenes of hunting and forest. Bávlos suspected that these tapestries, beautiful as they were, really were placed so as to catch and hold some of the heat in the room, like the reindeer pelts folk hung from the walls in the little houses back home.

Before too long, the bishop entered. He was not wearing a high bishop’s hat like Bishop Hemming had worn, but rather a simple little hat that fit close to his head. His clothes were elegant and ornate, though, and when Bávlos bent to kiss the bishop’s ring, he found that the bishop had a bewildering quantity of rings to choose from. Bávlos picked the one that the canon had kissed and then meekly stood behind Girard. He felt his knees shivering, but he suspected it was from fear rather than the cold.

“An ambassade from Sweden?” said Bishop Foulques with a smile. “But this is too strange! Indeed, it is a singularly amusing and unanticipated occasion. For we have another ambassade that has just arrived from that same land and is waiting in the other room! Shall I call them in?”

“Another ambassade?” said Canon Girard, turning to Bávlos. “Sir Pilgrim, do you know what this could mean?”

“No,” said Bávlos hesitantly. He thought of the ring he had traded at the hospital at Bermont to pay for Jacques’s white bread and pork. Had someone acquired the ring to now make calls on the bishop? Would there be two who claimed to have been sent by the king and queen, he with the letter and the reindeer, and the other with the ring? Bávlos felt the back of his neck growing hot as he stood alongside the canon.

“Well, said the bishop to his servant, “pray invite our other guests in.” Then he turned to the canon and to Bávlos and said, “Dear friends, it does me honor to present to you his excellency Bishop Hemming of Ĺbo and Master Peter Olafsson from the monastery of Alvastra.”

Bávlos froze in terror. There, entering the stateroom came the characteristic bishop’s hat and corpulent body of Bishop Hemming. Behind him stepped the gaunt and tired-looking figure of Master Peter, the man who had stood beside Fina’s mother Birgitta in the castle at Vadstena so long ago. In an instant, Bávlos saw both men recognize him, their jaws dropping in surprise.