Part II. The Hansa Lands and France

Chapter 34. Paris [November 18, 1347]

Cultural Explanations

|

Part II. The Hansa Lands and France Chapter 34. Paris [November 18, 1347] Cultural Explanations |

|

|

In this chapter Bávlos reaches Paris and meets Canon Girard. | ||

| Paris, Nôtre Dame, Canon Girard, Châlons, Bávlos, Nieiddash |

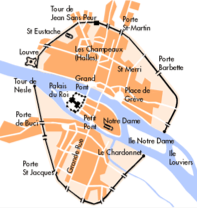

In this chapter, Bávlos arrives at Paris. Paris at this time was one of the largest cities in the world, with a population numbering between two and three hundred thousand. Originally a Roman settlement, Paris was centered on a single island, upon which now stood the Cathedral of Nôtre Dame, a hospital for pilgrims, the dwellings of the bishop and various canons of the cathedral and the royal court. Like ohter medieval cities, Paris was ringed by a wall, which helped control the flow of population into and out of the city. The island was located in the middle of the River Seine; the River Marne joined the Seine just to the east of Paris.

|

|

|

| Map of medieval Paris, showing the Petit Pont (Small Bridge) For original site, click HERE | Model of Île de la Cité, showing cathedral on the island and canons' residences to the left of the cathedral. Photo by Ilanana. For original site, click HERE | BModern map of Île de la Cité, showing many continuities of plan since the fourteenth century. |

We know a great deal about what Paris looked like in the 1300s. Bávlos enters Paris through its eastern gate and makes his way along the south shore of the river to the Small Bridge. There he becomes the center of a dispute regarding the proper toll for bringing a reindeer across to the island. The tolls cited here are accurate: for some unexplained reason, there was no charge for bringing a billy goat across the bridge. For further discussion, see Simone Roux Paris in the Middle Ages (trans. Jo Ann McNamara; Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009: p. 34). Although the medieval sources cited are explicit about charges for goats and monkeys, they make no mention of reindeer, so my scenario in the chapter is based largely on extrapolation.

|

|

|

| Cathedral as viewed from other side of bridge; the flying buttresses--an important addition of the early fourteenth century--evident on sides. | View of the cathedral from the front. Statue of Mary and Jesus in front of the rose window. | Detail, statue of Mary and Jesus. |

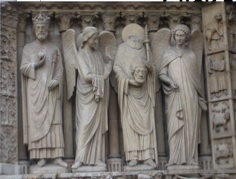

The Cathedral of Our Lady in Paris was an architectural wonder and a prominent part of the cultural and political life of medieval Paris. Begun in 1163, work continued on various aspects of the cathedral into the era when Bávlos visits. The flying buttresses that so dominate the building's exterior were added in the 1340s and represented the height of engineering know-how of the day. While certainly an impressive building, the cathedral was also an important spiritual and cultural center, employing some fifty canons and 120 chaplains who sang at the various masses celebrated every day within the cathedral, sometimes at its main high altar, but more often at various side chapels dedicated to particular saints and donated by wealthy aristocrats or guilds. When a canon could not attend his appointed mass, he could hire a subsitute to take his place, often a member of the cathedral choir, a group of men responsible for singing at cathedral services. Both canons and members of the cathedral choir lived in a separate district just south of the cathedral. In later times, this district was destroyed and the lands adjacent to the cathedral were convertd into park for use by the public. It is in this extinct clerical quarter that the fictional Canon Girard has his home.

Canon Girard questions Bávlos about skis, an implement of travel that he has read about in the writings of Saxo. Saxo Grammaticus (1150-1220) was an important Danish historian whose work became known even outside of Scandinavia during the Middle Ages. Girard displays considerable learning in knowing of Saxo's work: knowledge that could only be expected of someone of high clerical office, ensconced in one of the most privileged sees of medieval learning. Saxo's broader fame in Europe comes only in the sixteenth century, when published versions of his work begin to appear. That Canon Girard recalls Saxo's discussion of Sámi skiing is a testimony to his careful reading. Skiing was a common means of transportation for Sámi and other Scandinavians during the fourteenth century, but did not become widely known in Central Europe before the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

|

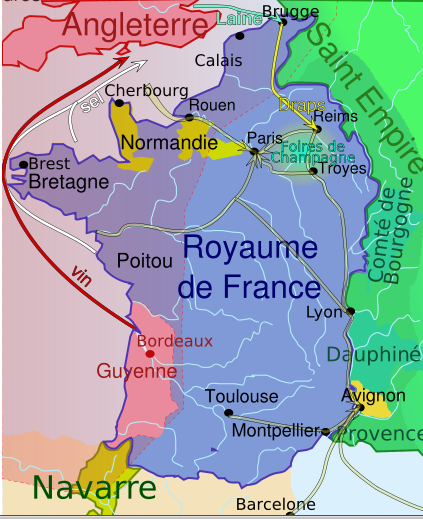

| Map of Hanseatic lands in fourteenth century. |

Bávlos uses the word dahkuágga as a translation for pretext. The word literally means "excuse." Canon Girard attributes the nascent Hundred Years' War to a struggle between economies—mercantile vs. agrarian—and suggests that the changing climate in the north of Europe is a punishment for northerners' abandonment of agricultural livelihoods. Climatologists suggest a different chain of causation: the deteriorating climate of the north made agriculture harder and harder in the norther periphery of the continent and in England, and the elite of these nations responded to this change through a shift toward manufacturing livelihoods. Whatever the case, it is clear that the Hanseatic economies of northern Europe exerted influence on the war, while the English king's bid for the throne of France was a clear attempt to secure agricultural wherewithal for his kingdom, increasingly dependent on the continent for food. A linchpin in this strategy was the Duchy of Guyenne, known to the English as Aquitaine. A land of rich wine production centered on its capital Bordeaux, the duchy had passed into English possession when Eleanor of Aquitaine married the English King Henry II in 1154. The duchy served not only as the English throne's foothold in France, but also as the source of most of England's wine throughout the Hundred Years' War. Wine was not a luxury so much as a necessity in an era when drinking water could lead to serious disease. In a very real sense, environmental history indicates, the Hundred Years War was a struggle over resources in a context of climate change.

|

| Map showing duchy of Guyenne/Aquitaine, supplier of vin, wine for England. Map courtesy Wikipedia Commons. |

Bishop Foulques was the nephew of Bishop Guillaume de Chanac. Guillaume had held the office of Bishop of Paris for a decade (1333-42) before advancing to the post of Patriarch of Constantinople, a title which he held from 1342 to 1348. On vacating the prestigious post in Paris, he arranged for his nephew to take over in his stead. As we shall see in the coming chapter, Bishop Foulques displayed the same favoritism (nepotism) toward his nephew Guillaume de Chanac (1320-83), who would later show the same favors toward his nephew Bertrand de Chanac, who became a cardinal from 1385 to 1401.

Bishop Hemming and Peter Olafsson of Alvastra did indeed visit Paris on a mission from St. Birgitta, calling on Bishop Foulques. We do not know the details of their meeting apart from the fact that the French were not convinced by Birgitta's visions that the English pretender had the legitimate right to the throne.

|

| Statues at doorway of cathedral. |