Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348

a free multimedia novel by

Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison

|

Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348 a free multimedia novel by Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison |

|

|

|

|  |

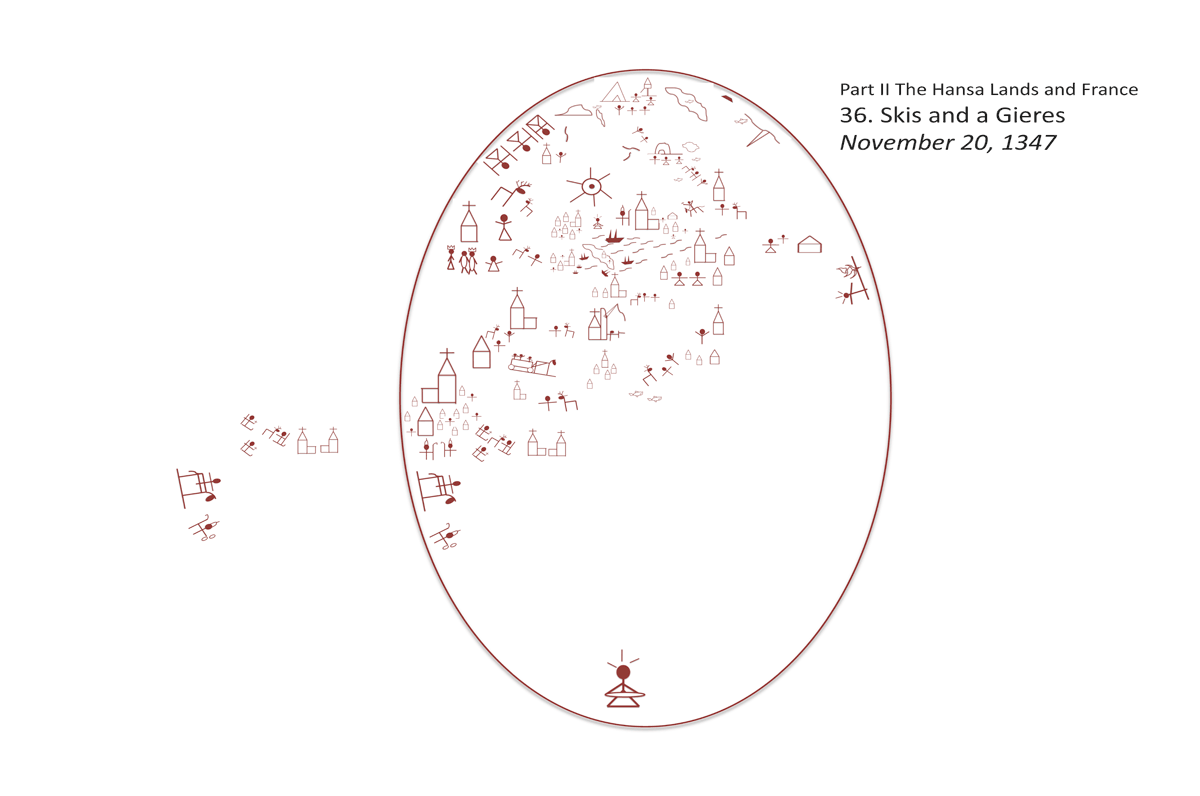

36. Skis and a Gieres (November 20, 1347)

Raphael answered: "Yes, I can go with him, for I know all the routes. I have often traveled to Media and crossed all its plains and mountains: I know every road well.

Bishop Foulques cordially invited the canon and Bávlos to dine with him and Guillaume that evening. Bávlos found the dinner sumptuous. Just when he thought the meal was over, the servants would return with more food, now of a different kind. And once that was finished, they would bring yet more. This eating went on for a very long time.

Bávlos was surprised at the learned interest all three clerics took in his land. Canon Girard asked Bávlos more about the wondrous planks that folk used for winter travel and how they functioned. “Of course, I have read what the erudite Saxo says of these planks,” said Guillaume, sharing in Canon Girard’s fascination, “and how the northern warriors could attack and escape with confounding speed because of them. But I have never understood how these things would work!”

Bávlos explained skiing as best he could, although he found it hard to describe such things to people who had never skied.

“These things are best experienced in person,” said Bávlos. “I learned from watching my father and working alongside him, and I don’t believe I could really explain how to make skis or even a gieres, in words, even in my own language.”

“A gieres?” said Canon Girard. “What is that?”

“It is our kind of wagon,” said Bávlos. It is long and narrow like a small boat, and the reindeer is harnessed by a line to its front and drags it along in the snow. A reindeer can pull a great deal in this way: a much larger load than it could bear on its back, or even a fully grown man and his supplies. When we travel long distances, we tuck children and the elderly in these little boats, so that they will not get left behind. But larger children must ride the reindeer. And sometimes the very elderly have to be carried by someone else. ”

“Ah,” said Bishop Foulques, “Your wagons do not have wheels!”

“They do not need them,” said Bávlos. “In my land, great journeys are always undertaken in winter, when the ground is hard and covered in snow, and the lakes and rivers are frozen. Then one can travel a great distance very easily in very little time.”

“It has been snowing all day today,” said Canon Girard musingly, “Master Bávlos, do you suppose you could build some of these planks for us to try tomorrow?”

“Leave me out of that, my boys,” said Bishop Foulques. “It would not do for the Bishop of Paris to be seen using unfamiliar devices! But I encourage you to try these things if Master Bávlos can supply them. In our land, Master Bávlos, virtually all travel comes to an end when the snows begin: the wagons do not do well in deep snow unless it has been packed down.”

“I shall be glad to show you how to make sábet, said Bávlos, “for I should make some for myself before continuing to Avignon.”

“Fine then!” said the canon delighted. “We shall begin making these contraptions tomorrow!” After sharing evening prayer with their host, the men took their leave, Guillaume promising to visit the canon the following day, and the canon and Bávlos walking home through the deep snow that now covered the streets.

It took Bávlos only two days to make three sets of skis along with a gieres. He felt that the work had proceeded at a blinding speed: normally, folk liked to take their time when making winter equipment, carefully shaping and bending the skis over a course of weeks. But they were short of time. The canon advised Bávlos that he should try to reach Avignon before Bishop Hemming and Master Peter, otherwise his pleasant gift of the reindeer and Birgitta’s urging for a holy year would be tainted by the unfortunate politicized message that the other ambassade was bringing, especially since they attributed it to Lady Birgitta as well. Bishop Foulques had spies in the royal palace and would be able to say when Bishop Hemming and his companion were finally received by the king and when they would make their start for Avignon. They were intending to visit Avignon first, and then to travel to the duchy of Guyenne, on the western coast, where they could find a ship to take them to England. Guyenne belonged to King Edward, and ship travel was frequent between the two places. But since the conflict had begun, few ships were permitted to travel between France and England, even though the distance was less.

“We shall, if you permit it,” said Guillaume on the afternoon of the second day, “travel with you toward Avignon, if you would like. I belong to the abbey of Saint Martial in Limoges, and I would propose we stop there. I have a dear friend who lives on an estate near that house, a young man named Pierre Roger. He is the nephew of the Holy Father Pope Clement, and we may avail ourselves of his aid to gain access to his uncle.”

Bávlos was astounded at the generosity and goodwill of both men. “I do not know what to say,” he said humbly. “It will be a great honor to travel with you.”

Guillaume touched his cheek tenderly. “It will be our pleasure!” he said.

Learning how to ski was a merry adventure for Girard and Guillaume. Bávlos was a patient and willing teacher though it was difficult for him to explain what they needed to do to ski as swiftly and effortlessly as he. “It is something your legs learn,” said Bávlos, gripping his staff and turning lightly to face the struggling men. “Once your legs know what they are doing, they will take care of everything. After all, you do not need to think about your walking, do you?”

“No,” said Guillaume, chuckling. “Quite right, friend Bávlos. I often think that different parts of our bodies have different minds of their own!”

“It says in Scripture,” said Girard, “that we are all one body in Christ. If that is so, dear Bávlos, I would hazard the guess that you are a leg.”

“I know what your bishop is, as well,” said Guillaume chuckling.

The skiing to Limoges took place in a far different manner than Bávlos could have imagined. True, the three friends skied for many miles each day, with Nieiddash happily pulling the new gieres, but they were followed by several servants on horseback who had extra horses along in case any of the friends should tire. Guillaume and Girard regularly resorted to their horses for spells, and the whole company found commodious inns or monasteries to stay in all along the route.

“This land is a gracious one,” said Guillaume, “I am from this region, although I was born in Paris. My uncle Foulques took me many times on visits here, while his uncle was still Bishop of Paris. All these places are as familiar as old friends and it warms my heart to show them to you, Girard, my friend from north of France, and to you friend Bávlos, from the distant north. Now to the west of Limoges—that is a different story!” he shuddered as he spoke. “For there lies Guyenne, the duchy of the perfidious Edward Plantagenet, brutal and revolting vassal of our king!”

“Yes,” said Girard sadly, “One would not wish to travel into that realm these days.”

“Such is a great sorrow,” said Guillaume. “It is a land rich in wine and produce.”

The friends slowly made their way southward to Limoges, and by the time they arrived at the grand monastery of St. Martial, both Guillaume and Girard were nearly as at ease on their skis as Bávlos. “How wondrous it is to move the body so!” said Girard. “I had no idea what fun the peasants have!”

“It is a merry life,” said Guillaume. “I must continue such exertions when we return to Paris. They seem to soothe my soul.”

“Christ liked a good walk,” said Girard, “Although I don’t believe he ever used planks!”

When they arrived at Limoges, Bávlos found that the Abbey of St. Martial was as grand a place as ever he had seen thus far. Guillaume told Bávlos that St. Martial had been one of Iesh’s first disciples, a boy who had supplied the Lord with loaves and fishes that he had miraculously multiplied and who had then gone on to become one of the Lord’s greatest Apostles. “From just five loaves of bread and two small fish, our Savior was able to make a great feast that fed five thousand men!” said Guillaume impressively. “Not counting the women and children of course! The remainders of the feast filled twelve wicker baskets.”

“What kind of fish were they?” asked Bávlos. The other men laughed. “Holy Scripture does not tell us,” said Guillaume, “although it does specify that the bread was made of barley flour.”

“I see,” said Bávlos. Here again he found the same strange tendency that he had noticed in Jacques’s tastes in storytelling: seemingly useless information was heeped upon the listener with great airs of importance while really interesting details were entirely left out. It occurred to Bávlos that the Bible would have been of far greater interest if it had been written down by a Sámi. “

Whatever the case,” said Guillaume to his friend, “we always eat well at this monastery as a result. And we are always thronged with pilgrims, many of them quite wealthy.”

Guillaume led the friends and servants to the stables of the monastery, where Bávlos carefully saw to the needs of Nieiddash, while the servants cared for the horses. They sent a servant to summon young Pierre Roger, and invite him to visit them there. Before long, Bávlos and his friends found themselves in a very commodious suite of rooms at the far end of the monastery, just down the hall from those of the abbot himself. Pierre had come to join them. He was slightly younger than the others, and Bávlos suspected that he was at least two years Pierre’s senior. Pierre took great delight in both Nieiddash and the skis and in hearing of the distant land to the north that Bávlos had left. Guillaume and Girard tried to teach Pierre how to ski using Bávlos’s skis, but they found themselves as incapable of explaining the art as Bávlos had been with them.

“You must learn it in your legs,” said Guillaume gravely. “There is no other way.”

Later that day, Guillaume took pleasure in showing their friends the treasures of the monastery. It had a massive courtyard, a school, a hospital, a scriptorium for writing and copying manuscripts, and a massive church. “This has been a place of Christian worship for already a thousand years!” said Guillaume impressively, “Even before the time of St. Benoît.” They descended beneath the grand church to an older church, that now lay beneath its newer and grander replacement. Below it, in turn, was an underground cave, where the reliquary of St. Martial lay. “Here lies the holy saint who brought the faith to this land and served as its first bishop,” said Guillaume. “People flock to our house for his help.” It seemed to Bávlos that the grand church and monastery somehow recalled the long and complex history of this people’s friendship with Iesh: their original and simple embrace of him, signaled in the small and comforting chapel of the reliquary; a time of greater power and confidence, signaled in the underground church; and finally, crowning it all, the magnificent basilica of the modern day, full of its beauty and riches. Bávlos’s own relation with Iesh was still in this early stage, he reflected. He wondered how many centuries would need to go by before his people would build such grand structures as this basilica in his honor.

That evening, after a fine dinner and prayer, Girard and Guillaume told their friend Pierre of Bávlos’s hopes to gain access to the Holy Father. “You cannot see my uncle,” said Pierre with firmness and regret. “I have received a letter from him just today. He has closed himself inside his palace between two fires, and none are allowed to visit him.”

“What do you mean?” said Guillaume in astonishment. “Your uncle our Holy Father has always been a man of great elegance and sociability! Is he suddenly turning ascetic like his predecessor Pope Benedict?”

“Certainly not!” laughed Pierre. “Nonetheless, he has sequestered himself during the time of the illness.”

“The illness?” said Girard. “What illness do you mean?”

“Have you not heard then?” said Pierre with excitement. “It is all the talk in these parts! A ship arrived in Marseille, bringing with it a pestilence of unsurpassed ferocity. It arrived on the Feast of All Saints, and thousands have died already!”

“Can this be true?” asked Guillaume. “A pestilence of such intensity?”

“It is spreading throughout the south,” said Pierre earnestly. “And it may even travel this way as well. I heard just today that your abbot has warned not to open the monastery’s doors to strangers who come from the south.”

Bávlos felt dizzy at the news. He recalled his dream of Ruto leaving the ship and beginning his rampage. “What am I to do, then?” he said helplessly. “How can I bring my reindeer to your uncle?”

“Are you certain my uncle would want this reindeer?” asked Pierre gently. “I mean, it is a very fine gift, worthy pilgrim Bávlos, and you have gone to great lengths to bring it to him, but my uncle is not one for animals, to tell you the truth. He thinks of deer as something to eat at dinner.”

“Ah,” said Bávlos quietly. He had always expected that Nieiddash would be sacrificed, but hearing Pierre say it in this way made him very sad indeed. Nieiddash had been a good and reliable partner in his journey and he had grown to love her. It was hard to imagine simply leaving her to be slaughtered for the Holy Father’s dinner, especially since meals in these parts seemed to consist of so many different meats and other foods served over and over again in waves. Nieiddash would just be one more course, and the little calf she was carrying an extra delicacy. “What would you suggest I do, then?” he said.

“Well,” said Girard, “how did the king and queen come to order you to bring Nieiddash to the pope?”

“They didn’t, at least, not at first,” he said. “In fact, now that I think about it, they weren’t involved in the original vision at all. Nor was the Lady Birgitta for that matter!”

“The original vision?” said Guillaume.

“Yes,” said Bávlos. “Christ spoke to me and he said that I should travel south with the stranger I had just met, a Brother Pekka, until Christ should tell me to stop. I would need to cross two great seas, and I should bring a two-year old female reindeer with me.”

“So then it was Christ that called you on this journey?” said Guillaume. “You are a pilgrim indeed.”

“It was so,” said Bávlos. “And somehow, in Sweden at the great castle at Vadstena, my journey got turned around. The Lady Birgitta told me I needed to see the Holy Father, and the king and queen gave me letters and—”

“Ah yes,” said Guillaume. “Do not fret. Such things often happen when one sets out on a holy journey, I have found. One never knows where one’s feet will lead if God is along for the ride.”

“But am I not to see the Holy Father?” said Bávlos, “Was the Lady Birgitta wrong?”

“I do not say that she was wrong,” said Guillaume. “Such would not be prudent. But recall our talk about her other vision and the harsh words she said of the kings. One can never be certain one fully understands what the Lord intends when he speaks his mind through a frail human being. Christ told the Lady Birgitta that a king would suffer, but it was not clear which one!”

“And how could that be with the Holy Father?” asked Bávlos.

“Well, it is simple,” said Guillaume. “Did the Lady Birgitta say that you were to visit the Holy Father, or did she mention Pope Clement by name?”

“She called him the Holy Father,” said Bávlos assuredly. “I know because I did not understand whom she meant for some time.”

The men laughed. “So, then,” said Guillaume. “Perhaps your Lady Birgitta’s vision refers to some other Holy Father,” he said. “Perhaps some Holy Father in the future!”

“Ah,” said Bávlos sadly. “Then my journey is far from over, I take it. Must I wait for a new pope to come along?”

“Well,” said Girard smiling and winking at Guillaume, “you could do that, of course. But perhaps the vision will be fulfilled if you simply meet someone who is not pope yet but will someday be the Holy Father!”

“Where could I meet such a man?” said Bávlos.

The men laughed again. “Friend Bávlos,” said Girard, “Do you not recall? Our Pierre here has Pope Clement as his uncle, how did you say it, his eahki. In fact, Pierre is named after his uncle, who was also called Pierre Roger before he was elected pope.”

“Ah,” said Bávlos nodding.

“And thus,” said Girard, “there is every likelihood, as you said yourself, that young Pierre here will someday be our pope!”

“Will he?” said Bávlos in wonder. “What luck I have! Then I can present Nieiddash to you!”

The men laughed again. “You can indeed, my gentle friend,” said Pierre warmly. “But I do turn him back to you to care for on my behalf. You can give me those letters of your king and queen and I shall see that my uncle receives them.”

Bávlos was overjoyed by this turn of events. He had met a Holy Father, not the current one, it was true, but a future one. And anyway, the current one was not available. And he had rendered up his Nieiddash only to receive her back again.

“Then what shall I do now?” he said, smiling with delight.

“Well, Master Bávlos,” said Guillaume, “Have you not forgotten your vision? I mean the vision you had yourself?”

“What do you mean?” said Bávlos.

“Why, you just told us,” said the professor, shaking his finger, “that Christ said you would need to cross two seas!”

“So I did,” said Bávlos thoughtfully. “I had thought that perhaps crossing the one sea in the north twice would count. I journeyed first from Ĺbo to Stockholm and then from Kalmar to Visby, and then from Visby to Reval, and then from Reval back to Visby, and finally to Lübeck.”

“Well, that certainly sounds like more than two journeys,” said Guillaume chuckling. “No, I would hazard the guess that Christ means you to travel further south, perhaps to Italy!”

“Yes,” said Pierre, his eyes wide, “Yes, to Italy! That is where I hope to go before too long!”

“Do you?” said Bávlos. “It is a nice place?”

“It is a fine place,” said Pierre. “And a holy place too! I should think that if our Lord wants you to stop somewhere, it might well be in Italy!”

“Then that is where I shall go!” said Bávlos eagerly.

“You must avoid all towns if you travel south,” said Pierre sternly. “The disease is rampant there now. We will supply you with provisions for your journey, and with your wondrous sábet, you should reach the coast in no time!”

An image of Ruto riding through the streets of French towns and villages grew in Bávlos’s mind. He saw people turning in fear, struck dead by the demon as he galloped through town.

“I shall certainly avoid all towns,” said Bávlos gravely. “Thank you Holy Father.”

“Perhaps we shall meet someday in Italy!” said Pierre.

“I hope that we will,” said Bávlos. “You are the first pope I have ever met.”