Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348

a free multimedia novel by

Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison

|

Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348 a free multimedia novel by Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison |

|

|

|

|  |

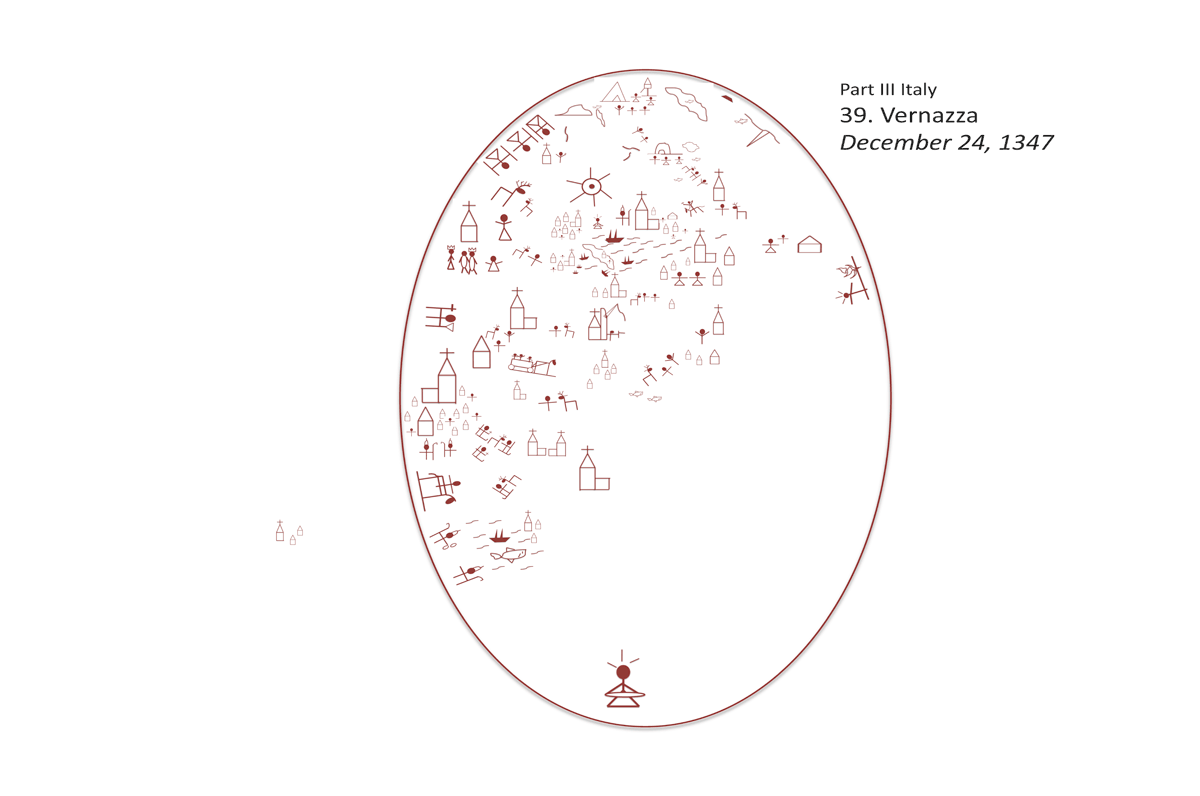

39. Vernazza and Corniglia (December 24, 1347)

The natives showed us extraordinary hospitality; they lit a fire and welcomed all of us beause it had begun to rain and was cold.

As soon as Bávlos reached the water, the weather seemed to abate. Bávlos felt his head sink into the salty waves, warmer than he thought possible given the month and season. When he surfaced a second later, he saw Nieiddash directly before him, paddling strongly, her back nearly floating above the water. With one arm hooked about the gieres line, and another grasping Nieiddash’s harness, Bávlos began to kick vigorously. He could hear the sailors behind him cheering as the wind died and the boat righted itself. Bávlos did not bother to turn around to look at the boat or its occupants, but searched the horizon for some destination toward which to swim. Not far before him the sky was clear and starlit above a rocky cliff of almost unimaginable height. Directly below the cliff, however, he could make out lantern lights and a large signal fire. There was a settlement nearby!

Nieiddash had sensed the shore as well and was already headed in that direction. Bávlos tried to keep up but it was impossible. The weight of his clothes and pack, along with his unwillingness to let go of the gieres, made him barely able to keep his head above the water. Before he knew it, Nieiddash had pulled so far ahead that Bávlos was obliged to release his grip of her and let her slip away.

“Now I shall die,” he said, “unless you send me help.” Suddenly, from below, Bávlos felt something prodding his feet. It felt heavy and forceful, and yet it had a playful insistence about it that reminded him of the way that Nieiddash nudged him with her muzzle. Bávlos lifted his legs apart in fear. The thing began to prod his thighs now instead. Soon, he felt a strong wide object like the back of one of a shovel press hard against his thigh and push him forward. He felt himself lifted up in the water and thrust forward in a jolting fashion. He was almost even again with Nieiddash now. Again, the pressing and thrusting occurred: something was helping him to shore! Bávlos looked to his side,: a large smooth fish rose to the surface of the water and exploded a spray of salty vapor into the air before rolling back under the surface. Farther beyond he saw another such fish breach and sink, and another behind that. They were dolphins, like the ones that the strangers on the northern coast called “white noses” but with different coloring. He felt the wide smooth head of one of these beasts beneath him. It pushed between his legs and lifted him up. Bávlos was riding on its back and it was heading him toward safety. Within what seemed like seconds, Bávlos felt the beast sink below him and leave him at last. He found that he could stand now, although the pounding waves of the ocean pushed him down. He turned to thank the animals.

“Thank you, kind dolphins!” he called.

“Thank San Nicola,” came a voice in reply. Bávlos crossed himself and prayed as directed. Then he turned and struggled to land, pulling the floating gieres behind him.

“Thank you for this help, good San Nicola,” he gasped, falling into the sand at the water’s edge. After lying in this way he knew not how long, Bávlos suddenly awakened and rose to his hands and knees. He was cold and shivering, his clothes heavy with water. Nieiddash was standing by, nudging him. He heard the ringing of a bell. With difficulty, he rose to his feel and followed the sound. Not far from where he had come to shore, perched up above the water in a little town’s main square, Bávlos saw a small church. The town itself was sandwiched snuggly on a small bit of sloping land that lay above the water’s level and below the steep incline of the cliffs. In several directions, narrow lanes led off the little square, serving as twisting thoroughfares for the villagers who lived in the small one- and two-storey houses that lined the streets. As the bell rang, Bávlos could see dozens of people making their way toward the church. Deep in the night though it was, the people were coming to mass!

Bávlos followed the crowd inside. Despite his dripping tunic and now chattering teeth, no one seemed to take any notice of him. The people seemed to be coming in family groups and they huddled close together in the crowded little church. The combined body heat of the assembly seemed to warm Bávlos, who stood behind the throng at the very back. From where he stood, he could both see the altar and hear the crashing waves of the sea. Mass began. Bávlos was struck by the robust and lovely singing of the community and their reverent attention during the ceremony. A small priest, a good head below Bávlos in height, presided, turning around frequently to throw his arms wide and greet or cheer his flock. How happy they all seemed; how content Bávlos felt to be in their number. After mass had ended, people seemed to have suddenly realized they were in a group. They turned right and left excitedly, shaking hands and laughing. They had ready handshakes for Bávlos as well, although he could see their eyes grow wide with surprise when they took in his appearance and dripping clothes. As they began to file out of the church and into the crowded square, the children caught sight of Nieiddash and shrieked in surprise. No doubt they had never seen such an animal in their tiny village by the sea. As the parishioners filed out, the little priest rushed to the back of the church to greet Bávlos.

“Good evening, buon Natale!” he cried, pumping Bávlos’s hand with jovial vigor. He was a pudgy man, with short black hair and a prominent nose. He had clearly noticed Bávlos from the beginning but had only been able to greet him now. He spoke to Bávlos in the local language, but Bávlos understood little of what he said. So he switched to French instead. “Good sir, you look soaked through! Have you been walking all the night to get here for mass?”

“Actually,” said Bávlos, blushing, “ I came by sea.”

“By sea?” cried the priest, “Where’s your boat?”

“No boat,” said Bávlos. The priest took in his appearance from head to toe. “Come to my house, friend, you need some warming up!”

“Thank you,” said Bávlos. “You are a Frenchman?” said the priest. “Around here we don’t say merci, but grazie. We speak the true language of the Church around here.”

“Grazie,” said Bávlos. He raised a finger. “I must take my animal as well.” He hurried down to the shore, where he had left Nieiddash tied by some beached boats.

“Why, a deer!” cried the priest. “You travel with a deer!”

“Yes,” said Bávlos, “In the land of my father the deer is how we travel!”

“Even over water, I see!” said the priest, shaking his head in wonderment. “Good sir Pellegrino, come to my house.”

“Pellegrino?” asked Bávlos.

“Pčlerin,” said the priest. “You travel for Christ and the saints, yes?”

“That’s right,” said Bávlos. “I am a Pellegrino.”

“Then you need a shell,” said the priest, finding a small cockleshell in the sand. “Show this to people and say you are a pilgrim. Good people will help you then.”

“Thank you,” said Bávlos. He was beginning to understand the priest’s words better and better now. They often sounded like French words, though pronounced a little differently. He had the impression that the priest was speaking very slowly and clearly for his benefit. Still the same, it sounded like a more relaxed and jovial language than the one they used in France. It made him smile just to hear the man speak.

He followed the man to a small house close by the church. From what Bávlos could tell, it had only three rooms: a main sitting room, with a fire in its grate, a kitchen behind it, and a small bedroom to its side. The little priest pulled a second chair up to the fire and motioned for Bávlos to sit.

“Now dinner!” cried the priest. “The people are very good to their priest on Natale.”

“Natale?” asked Bávlos.

“Noël, as you say.” Still Bávlos looked confused.

“Why the day when Notre Dame have birth to the little baby Gesů!”

“Ah,” said Bávlos, nodding. Tonight was Iesh’s birthday, the night when he had become a man, as Pekka had explained so long ago. Advent was over. That was the reason for the mass so late at night: they were celebrating the Savior’s nighttime birth. “Natale!” he said, “Good Natale!”

“Good Natale also to you!” smiled the priest. “And now, friend pilgrim, take off your soaking clothes and string them by the fire. I will give you a spare cassock to wear.” He made motions as of undressing, tugging at Bávlos’s clothes. Bávlos gladly complied.

The priest’s cassock was strangely long and woven of a coarse fabric, but it was warm and dry. “Thank you,” said Bávlos. “Thank you for everything.”

“It’s Christmas!” laughed the priest, shaking his head, “and you are my Christmas guest!” Christmas guest. The name made Bávlos think of the midwinter stranger who came through his father’s lands at this time of year. He was huge and dangerous, that ogre Stállu. Bávlos remembered the fear he had felt on the night of Stállu’s coming: it was crucial for the children of the household to remain absolutely silent that night, otherwise Stállu would murder them and drink their blood. During the day before, Bávlos and his brothers and sisters would always carefully gather up every stick and stone around the hut that could impede Stállu’s gieres, so that when he traveled by, his team of rats and other vermin would not become ensnared. And Bávlos remembered bringing in loads and loads of snow, to make a great pot of water for Stállu to drink should he decide to come inside. Better water than blood, after all! Now it seemed to Bávlos that he had become the Stállu, arriving in the middle of the night, hungry and forlorn. Perhaps Stállu also felt cold and lonely in his life out in the cold? Bávlos had never had such a thought before.

“Thank you again,” he said to the kindly priest.

“Christmas is for sharing, for sharing!” said the priest. “Eat! We have plenty of food tonight!” And so they did. The villagers had brought their pastor every sort of Christmas treat imaginable—cold meats and vegetables, a hot stew, bread, little cakes covered in honey, nuts and fruit. Bávlos ate his fill and then some. Then he thought of poor Nieiddash, who remained outside.

“My deer,” he said.

“Ah yes, your deer!” said the priest. “Let us tend to him at once!” Together they led the reindeer into a little stable behind the house. The priest gave Nieiddash some hay and grain in a stall next to his small donkey. Bávlos pumped some water from the well in the town square into a bucket that he placed before the deer.

“Don’t drink it all,” he whispered to Nieiddash in Sámi. “Leave some in case a visitor comes!” The men returned inside and Bávlos slept gratefully and contendedly by the fire.

The next morning, the little priest was up early, readying himself for morning mass. Bávlos rose and found his clothes still somewhat damp but dry enough to wear. He pulled off the borrowed cassock and returned to his Sámi dress.

“Fine leather,” said the priest, feeling Bávlos’s tunic, “beautiful and long-lasting I’m sure.”

“Yes,” said Bávlos. “My mother made it.”

“Will you stay to breakfast?” asked the priest.

“Thank you,” said Bávlos. He went with the priest into the church sacristy, where the priest’s vestments were stored. There were robes for every season, all in gorgeous colors, with elaborate embroidery down the back.

“The back,” said the priest, “is the most important part. That’s what people have to look at for nearly the entire mass! And when I’m facing the people, well, I hope they look at my face and not my robes!” Bávlos thought that this was an interesting statement, since many of the clergy he had met so far seemed much more interested in having people look at their robes than getting them to pay attention to their faces. This priest seemed a very humble man, well suited to the small village where his little church was located. In certain ways he was very much like Father Jens back in Hattula Church, though he was not a foreigner to his community.

When mass was over, Bávlos and his host returned to the priest’s little house. Parishioners stopped by constantly, dropping off dishes of food, shaking the priest’s hand. “By the way,” said the priest, “my name is Father Giuseppe. What are you called?”

“I am called Bávlos,” said his guest.

“Bávlos?” repeated the priest, “Paolo! You have come like your patron saint arrived in Malta: shipwrecked on her shores!”

Bávlos smiled. “I should be leaving soon,” he said. “I think I need to clear this mountain and find some sustenance for my deer.”

“It is a long walk up,” said the priest, “from Vernazza to Corniglia. But once you cross over the mountain above Corniglia, the terrain becomes milder indeed. Are you headed for Rome?”

“I think so,” said Bávlos, “if Iesh wishes it so.”

“Aye, God willing,” said the priest. “It looks like your way has been difficult up till now.”

“But I have met many who have helped me,” said Bávlos. “Like you, good father.”

Suddenly there came a knock at the door. A small woman, hardly more than fifteen, had come to the doorway. She had dark hair and wide, brown eyes. She was carrying a bundle in her arms. Bávlos could see the tiny head of a newborn child. “Please, Father Giuseppe!” said the girl, curtseying. “Maddalena!” cried the priest, “Come in! Merry Christmas!”

“Merry Christmas,” she said. “Father—“

“Is that your baby?” cried the priest excitedly. But then he seemed to reconsider the situation and whispered in hushed tones, “Ah, so you’ve had a child.” The girl nodded rapidly, her eyes downcast. She began to cry. As her tears fell, she suddenly caught sight of Bávlos, standing behind the priest, watching her intently. She straightened up, wiping her tears quickly.

“When was the little one born?” asked the priest gently. “Last night,” said the girl, her eyes tearing again.

“And you had the baby all by yourself?” asked the priest. “Signora Pontorno helped me,” said the girl. “She told me to come to you today and ask you what to do.”

“You have done well to do so,” said the priest. “We must count our blessings! You have a little child—“

“A boy,” said the girl.

“Ah, a little son,” said the priest. “And you and he are both healthy and fine.”

“Yes Father.”

“Come, we shall baptize him now.” The priest led the girl back to the church, with Bávlos walking along. “Paolo,” he said, “You can assist me.” Bávlos nodded. “This Paolo,” said the priest, “has come as a pilgrim from France. If you would like, he can escort you to your parents’ home in Corniglia. You can show him the way and he can help you make the trek.”

“Yes Father,” said the girl, looking at Bávlos.

“Well then,” said the priest, “What shall we name the child?” The girl looked blankly. She had not thought of a name. “What about your father’s name, Bernardo?” asked the priest. The girl shook her head and looked down. Bávlos guessed that the father would not be pleased to have this little child bear his name.

“What about Nicola?” said Bávlos.

“Nicola,” said the girl, brightening. “Yes, Nicola! Thank you, sir, for the suggestion! San Nicola has always been a help to girls in need!”

“And to others as well,” said Bávlos, smiling.