Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348

a free multimedia novel by

Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison

|

Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348 a free multimedia novel by Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison |

|

|

|

|  |

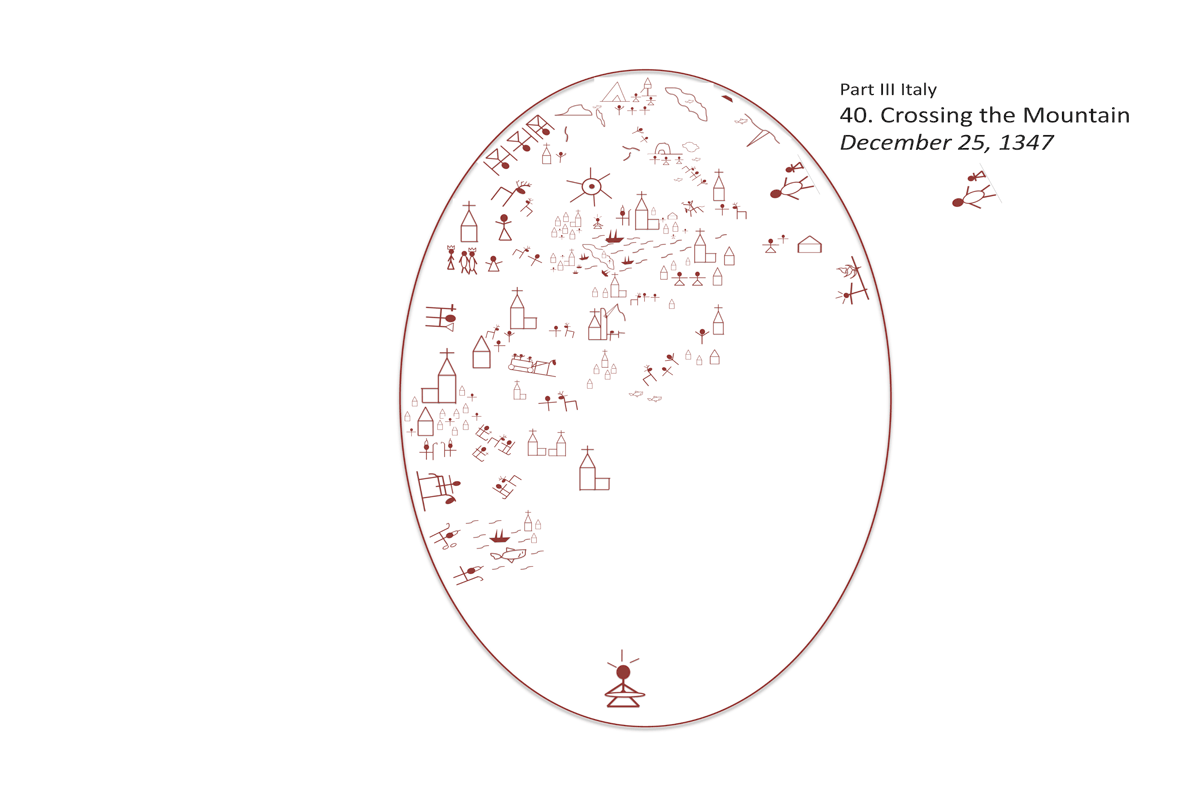

40. Crossing the Mountain (December 25, 1347)

Let the children come to me, and do not prevent them, for the kingdom of heaven belongs to such as these.

After the baptism, the little company retired into the priest’s home for another meal. The girl ate quite a lot in fact, but Bávlos and Father Giuseppe just ate a little, mostly to keep her company. Then Bávlos slipped away to convert his gieres into a smaller pack suitable for tying to Nieiddash's back. It took some work doing so, but Bávlos sensed that in this warm land, he would have no further use of a gieres.

At length, Father Giuseppe reminded his guests of their need to cross to Corniglia.

“You must climb the mountainside while the weather and light is good,” said the priest. Bávlos and Maddalena made ready to leave. “Now you must tell your parents, Maddalena,” said the priest sternly, “that you have been here to see me and that the child is already baptized. Tell them that I will come to see you all in two days and that I will be anxious to see how little Nicola is getting on. A child born on Christmas eve is a blessing indeed: perhaps he will someday be the pastor of this parish!”

Maddalena nodded quietly, her eyes still downcast. It was only when Bávlos returned from the stable with his reindeer that she seemed to react to the things around her. “A deer?” she cried.

“Yes,” said Bávlos, “In my country we use these deer as you use donkeys here.”

“France is a wondrous place,” said the girl. It had begun to rain. Father Giuseppe warmly took his leave of them all, solemnly making the sign of the cross over them as he backed away toward the church.

“I have another mass,” he said, bowing as he slipped away.

“Well,” said the girl, embarrassed and tongue-tied, “the path to Corniglia begins over here.” She began to walk, the infant pressed to her breast.

“Maddalena,” said Bávlos, “please, I have made this place in my deer's pack for the baby to ride.” He showed the girl how he had adapted the gieres as a riding pack.

“In there?” cried the girl, “But how will he keep warm?” Bávlos thought the question a little silly, since to him the day felt like a warm spring afternoon rather than a winter morning.

“I have these,” said Bávlos, showing the girl his store of pelts. “The child will be very content in there.”

Before long they had arranged things as Bávlos had suggested. “He is all right in there?” asked the girl nervously.

“He is all right,” said Bávlos. “In my land, this is always how babies travel. He is as Laurukash on the Stállu’s back!”

“Laurukash on the Stállu’s back?” asked the girl. “What does that mean?”

“Do you not know who Stállu is? asked Bávlos.

“No, I have never heard of that person,” said the girl.

“Ah,” said Bávlos. “So at this time of year, you don’t worry about a visitor coming who might kill and eat the children of the household if they make noise?”

“No!” said the girl with a tone of terror. “There is no such threat here.”

“Well, that’s good,” said Bávlos. He was glad to hear that Stállu did not torment these people as he did folk back home.

“But who is this Stállu?” asked the girl.

“Stállu?” said Bávlos. “Well, he’s a, he’s a—“ He had no idea how to explain what an ogre is in the girl’s language, so he acted part, stamping heavily with his feet, glowering and sneering as he walked. The girl was startled at the performance.

“Oh, he looks dangerous!” she said.

“He is!” said Bávlos nodding. “You have to be careful around Stállus, and—” he had no idea how to say “clever” or “brave” in this girl’s language, so he simply struck himself hard on the chest.”

“Ah,” said the girl, “You have to be brave!”

“Yes,” said Bávlos, “Like Laurukash on Stállu’s back.”

“I do not know that story,” said the girl.

“It was like this,” said Bávlos. “Stállu was walking over a mountain one day and he came upon a boy. The boy didn’t have time to run away from the Stállu and there was no space on the path to hide from him either.

‘Ahaa!’ snarled Stállu, grabbing the boy. ‘I shall eat you for lunch!’

‘No!’ cried the boy, ‘I can help you!’

‘How can you help me?’ asked Stállu.”

Bávlos gave a growl and sneer as he acted out the ogre’s words. The girl was clearly enthralled by the tale.

“‘I can help you carry that pack on your back!’ said the boy. Now Stállu had been to a city and had lots of, lots of—” he searched for the word.

“Money? Silver? Treasure?” asked the girl.

“Silver!” said Bávlos, “He had lots of silver and his pack was very heavy.

‘You can help me?’ asked Stállu, ‘How?’

‘Well,’ said the boy, ‘You carry the pack from below, and I will carry it from above. That way it will be half the load for you!’

‘Oh!’ said Stállu. ‘But how will you carry the pack from above?’

‘Easy,” said the boy, ‘Just lift me up on top of the pack and I will start carrying it from there.’

Stállu lifted the boy and placed him on top of the pack on his shoulder.

‘Now let’s go!’ said the boy. Stállu marched off with the pack and the boy on his shoulder.”

The girl laughed. “This Stállu is not too smart,” she said.

“No,” said Bávlos, “That is the good thing about Stállu. Anyway, after a while, Stállu was getting tired. So he called out to the boy:

‘I am getting tired, what about you?’

‘I’m not tired at all!’ said the boy. Stállu grunted and kept walking. After another hour he said:

‘Now I’m getting quite tired.’

‘Not me!’ said the boy. So Stállu kept walking. Finally, Stállu was really, really tired. So he said:

‘Boy, I don’t know how you do it, but I need a rest!’

‘Okay,’ said the boy, ‘Why don’t you sit down over there where you can put your legs out over the edge. That will give them a rest.’

‘Good idea!’ said Stállu. So he put down the pack and the boy and sat down on the edge of the cliff. And just as he sat down, the boy ran at him with all his might and pushed him off the cliff! Stállu fell down the mountain and was killed on the rocks below and the boy took the whole pack of silver back to his home!”

The girl laughed at the story. It had made the climb along the narrow path and cliffs more enjoyable. They had made it up a very steep climb and were now walking through an ancient olive grove on a path that was nearly level far above the sea. “This Stállu sounds dangerous but dumb,” she said.

“He is both those things,” said Bávlos. “And girls particularly have to watch out for him.”

“Why?” asked the girl, looking anxious. “Because he’s always looking for a girl as a, a—”

“A wife?” asked the girl with an involuntary gasp.

“Yes, as a wife!” said Bávlos.

“But who would want to give their daughter to such a monster?”

“Someone with no choice,” said Bávlos. “I will tell you about it. One time, Stállu came to a home of one of my people and he wanted to marry a girl. They didn’t want to give him one but he was big and—” he growled and snarled— “and they were afraid. He said he would kill them all unless he got a wife. So they gave him their first daughter to take home with him.”

The girl was listening very intently now. Bávlos continued: “When he got her home he said:

‘Wife, I will treat you well, so long as you cook for me the animals I bring home.’

‘I will do so,’ said the girl. But the next day, Stállu came home with lots of, lots of—” He acted out the crouching manner and twitching nose of a rat.

“Rats?” gasped the girl.

“Yes, rats!” said Bávlos. “He came home with lots of rats. And he threw them down on the table.

‘Cook these!’ he ordered.

‘Not on your life!’ cried the girl. Stállu was angry and threw her in a pit.

‘I will eat you later!’ he said. Then he went back to the same family and asked for a new wife. He got a second girl. Again, she wouldn’t cook his rats, so he threw her in the pit too. Then he went and got third daughter. She came home with him and acted nice. She cooked the rats and made a stew. When it was done, she called out sweetly to Stállu,

‘Husband, eat!’

‘Wife,’ he said, ‘You have done well.’

‘Husband,’ she said: ‘I like it here. But I want to send some gifts back to my parents. You must carry them.’

‘I will gladly,’ said Stállu. He was proud that his wife was so resourceful and he looked forward to impressing her family with the things she sent back.

‘I will pack the bag here,’ said the girl, ‘and after you come back from hunting tomorrow, you will see the bag by the door. Drop the game off by the door, take up the pack and bring it to my parents. And don’t look inside! I have eyes that can see you wherever you go and whatever you do!’

Stállu trembled. His wife was a powerful woman! The next day, Stállu did as he was told. He came to the hut with a wild deer on his shoulders that he dropped down to the ground. Then he took up the pack and started at once for the girl’s parents. The pack was actually holding the girl’s older sister, whom the girl had rescued from the pit. After he had gotten about half way to his parents-in-law’s house, Stállu grew very tired. He sat down and made to look into the pack.

‘I wonder what my bride has put in this pack that is so heavy?’ he said to himself. The girl in the pack heard what he said.

‘Get off your bottom, husband!’ she called out in her sister’s voice, ‘Did I not tell you that I have eyes that see you wherever you go and whatever you do?’ Stállu jumped to his feet, took up the pack and walked the rest of the way back to his wife’s home. As he neared the house, though, the sister in the bag again called out:

‘Husband! Dinner is ready! Drop that pack by the door and hurry home at once!’

Stállu was so hungry by this time that he did exactly as he was told. He hurried home to where his wife had made him a delicious roasted deer.

‘Husband,’ she said again, ‘I have still more things to give my parents. Let us do the same tomorrow!’

‘Yes, wife,’ said he, his stomach full and contended. The next day, the girl placed her second sister in the bag alongside the door of the hut. Stállu returned from his hunting with a great elk and dropped it by the door. He took up the pack at once and started back to his wife’s parents’ home. Again, when he got about half way there, he grew tired and irritated and sat down and made to open the pack.

‘What can my wife be packing in these bags?’ he muttered to himself. The second sister heard him and called out:

‘Husband, did I not tell you that I can see you wherever you go and whatever you do? Get on with your errand or there’ll be no dinner for you!’

Stállu swung the pack back onto his shoulder and hurried the rest of the way to the parents’ house. When he got close to the house, the girl inside the bag called out:

‘Husband, dinner is almost ready! Drop that pack by the door and hurry home!’ Stállu did as he was told. When Stállu got home, he found a delicious roast of elk waiting for him. His wife said:

‘Husband, I have one more bag to send home. Will you bear it for me?’

‘I will,’ said Stállu. The next day, once her husband had gone, the girl took her clothes and put them upon a tree stump on the other side of the pond by Stállu’s house. Then she made holes in the ice and covered these in straw and snow so that Stállu wouldn’t notice. Finally she climbed into the bag by the door to wait for her husband’s return. When Stállu came home, he was carrying a huge bear. He saw what he thought was his wife across the pond.

‘Wife,’ he called, ‘I have brought home some meat!’

‘I will cook it!’ called the girl from inside the bag. ‘You take that last bag to my parents!’

‘I will,’ he said. He lifted the bag onto his back and headed off to the girl’s family. But when he got halfway there, he grew tired again and sat down, intending to open the bag.

‘Husband!’ the girl called from inside the bag, ‘Didn’t I tell you? I have eyes that see wherever you go and whatever you do! Now get a move on to my parents!’ Stállu sprang up at once and hurried to his in-laws, where he dropped the bag. Then without even waiting for a greeting he turned and hurried back to his home.

When he got there, he saw the bear lying by the door and his wife across the pond looking at him.

‘Wife!’ he called. ‘What’s the meaning of this? Why haven’t you cooked my meat?’

The tree stump didn’t answer.

‘Wife!’ he called again, ‘Don’t make me angry! If I have to come over there to get you I will!’

The tree stump made no move. ‘

Wife!’ he cried in a fury, ‘I am going to beat you black and blue!’ He raced across the pond to grab his wife, but as he stepped on the ice he broke through into the freezing water. He scrambled out as fast as he could but the ice broke beneath him again. And then he managed to climb out again but once again the ice broke and he sank into the pond a third time. Now he was too tired to climb out any more and still a long way from shore. He froze to death and the family never had to worry about him again.”

Maddalena laughed at the tale. “That girl was clever,” she said. “But what happened after that?’

“Well,” said Bávlos, blushing a little, “the girl had a son about nine months later.”

“A son?” gasped the girl. “With the Stállu?”

“Yes,” said Bávlos. “There are some families that have Stállus in their past.”

“And what happened to this child?” asked Maddalena, glancing at the pack on Nieiddash’s back.

“He became a fine hunter and a fine husband,” said Bávlos. “No one was better at finding game than he, and his family became very large and rich.” The girl smiled. The trek over the cliffs to Corniglia was steep and cold and wet, but the company had little trouble. Maddalena knew the trail like the back of her hand and she seemed little worse for the wear for having given birth only the night before. Bávlos and Nieiddash felt reinvigorated to be on a mountainside again, stepping between rocks and feeling the wind blow. Now that the rain had stopped, Bávlos found that the landscape reminded him of home, except for the stunning blue sea that came into view every now and then as they picked their way through olive groves and forest. How wide and peaceful the sea looked from the cliffside, far above the water!

“It is beautiful here,” he said.

“Is it?” said the girl. “It is the only place I have ever known. Surely the city of Paris must be finer!”

“This place is more beautiful than Paris,” said Bávlos, truthfully. “It is a good place for you, good for little Nicola.”

The girl smiled. She appreciated this worldly foreigner’s kind words and his gentle ways. ‘No doubt he is a nobleman,” she thought to herself. “Although he tells stories that are more enjoyable than I think nobility would tell.”

At last they came to a hillside beyond which Bávlos could see the first of a number of houses. “We are coming to my parent’s home,” said the girl aloud, suddenly fearful. “You must not come in. My father will be furious if he sees you and he will try to kill you. Come, give me little Nicola now.”

Bávlos and the girl extracted the tiny baby from his warm cocoon of fur and wrapped him again in the fabric blankets the girl had been using before.“I feel like Stállu’s wife,” she said, looking down.

“Her son grew up to be a great hunter,” said Bávlos. The girl smiled and straightened her back. She turned toward her parents’ home and began to walk resolutely toward the door. Bávlos watched as she slipped into the front passage and disappeared from view.