Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348

a free multimedia novel by

Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison

|

Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348 a free multimedia novel by Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison |

|

|

|

|  |

41. Approaching Pisa (January 3, 1348)

The wind blows where it wills, and yoiu can hear the sound it makes, but you do not know where it comes from or where it goes

Buonamico Buffalmacco opened his eyes only a slit as he awoke that chilly January morning. The neighbor’s rooster was crowing. It was morning, but unwholesomely early, as far as he was concerned. He closed his eyes again. He was an eagle, no a falcon: soaring high against a clear blue sky. He felt the wind rushing against his face and he opened his mouth to let out a piercing and fearless cry. Far below, he could see a countryside of green fields and pine forests, dotted with discrete cities enclosed in towered walls. In the city directly below him, he could make out its grand cathedral and octagonal baptistery. And beside these, the large flat outline of the Camposanto, a massive rectangle in the green earth below. On the horizon, he saw the sea, its grey waves crashing on the shore. He turned inland though, and flew swiftly northward, along a road that wound through hills and valleys. And then he spotted him. Letting out another cry, he closed his eyes to slits and dove. The ground grew rapidly clearer before him: trees that had started as tiny spots now loomed leafy and substantial; a river that had started as a thin blue line now swelled into a greenish snake. All came into sharp relief. He realized that he was approaching a man, a knight. He rode upon a grey horse with a bridle studded in silver. The knight wore a shining mailshirt and a cape of deep blue. He was young and handsome, with eyes of vivid blue. He whistled and held out his right arm. Buonamico felt himself shift his wings and adjust his approach, bending his wings outward at the last to slow his speed. With a graceful flutter he landed on the knight’s arm.

“There you are my Buonamico,” said the knight in an accent that sounded both foreign and refined. “Are we almost there?”

Thud. The dream was over. The housekeeper Signora Bartoli had just slammed the front door with her characteristic heaviness and upset the bowl of pigment that the apprentice had left too close to the edge of the table. A cloud of brown earth rose above the toppled pot, drifting outward to mix with the other particles of the dusty air and settle upon the cluttered floor. Paint pots, brushes, mortars and pestles, soiled cloths, empty bottles, boots, hats, and a painter’s hooded tunic lay jumbled on the floor. The old woman was clattering plates in the next room, pulling together a simple breakfast for her boarders as well as for herself. She was scolding Buonamico’s apprentice, whose bedroom quarters doubled as the household’s kitchen.

“Get up you sluggard! The sun is high! It’s no time to be lying about!”

“Why not?” thought Buonamico to himself. Why was it so important to these peasant types to rise at the crack of dawn and bustle about and make lots of clatter? Why not sleep, dream? Night was Buonamico’s time, when his faculties were at their finest and the images of his art rose effortlessly in his mind. Every hour of late night musing, aided by a cup of wine, was worth two of morning frenzy, as far as he was concerned. Moments like those were the life of his profession: the inspirations that would lift his art from mere dabblings to true masterpieces. Buonamico closed his eyes again and tried to recover the dream of the bird. How beautiful it was to soar and dive; how paltry life seemed here below by comparison. Yet these women, with the prattling tongues, their shaking heads, their wagging fingers! They could see nothing but their rigid norms. What sort of life was that for an artist? To be chained to a farmwife’s regimen, subjected to a peasant’s dictates.

Buonamico remembered his earlier days, when he was an apprentice to the painter Tafi. Master Tafi had always wanted to wake up early, before even the sun, to start the day’s work. And so, of course, he forced all his workshop to do the same. Until Buonamico fooled him, that is. The shrewd apprentice had devised a way of affixing candles to the backs of large roaches that infested the master’s home. One night, when all were asleep, Buonamico had released a set of such animals, the candles on their backs burning brightly. They crawled too and fro over the master’s floor and wall, scaring the poor man nearly to death. Buonamico told his foolish master that the lights were devils plaguing him,

“For devils always resent painters, not just because we show them in all their ugliness, but also because we show Christ and Maria and the saints in all their beauty.” Tafi had been moved by his apprentice’s speech and asked how he could get shed of such hauntings.

“Sleep late!” Buonamico had said, and the painter had followed his advice. But now how was he to stop the clangings and goings on of this old nag of a housekeeper? There was nothing for it; he would have to rise. But with a will of effort he took hold of the image of the bird and held it in his mind’s eye as he returned to waking consciousness. It would remain in his memory now, dim but still persistent.

Bávlos awoke well before the dawn. The birds had begun their calls, strong and insistent, and Nieiddash was nudging him where he lay. In the clear sky above the trees he could still see stars, but they were fading as the sun neared the horizon and began to color the sky.Spring came early in this land: back home, there would still be months of snow and cold before the melting time would begin. Or perhaps this was the winter of this land? There was no snow and many of the trees still had their leaves. The brush in the fields was brown but still alive. Bávlos rose to check the snares he had set the night before. Down the hill, at the edge of the meadow, he had caught a fat grouse. With a flick of the wrist he wrung its neck.

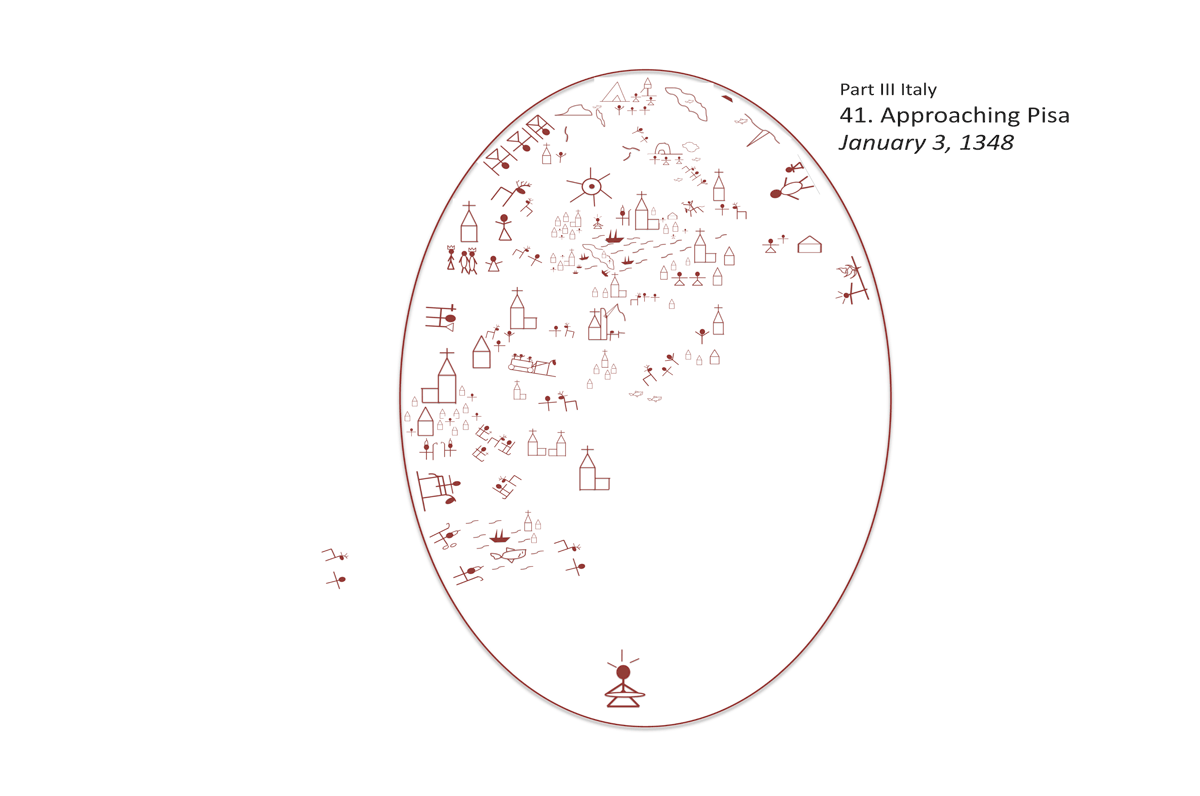

“A fine breakfast,” said he. He rekindled his fire from the night before, gutted and plucked the bird. Then he cut it into pieces to roast on sticks beside the fire. While the bird cooked, he settled down beside the fire to work on his drum. In the tumult of the great leap into the sea, the drumhead had become ripped, and Bávlos had used the back of King Magnus’s fine letter to make a new drumhead. It was fine and white and made a bright sound when stretched taught. The waters of the sea had destroyed the images on the old drumhead: the depictions of Sieidi and the Old Women and the Wind Man and all the other beings that Grandfather Sálle had found so useful in his work. Bávlos remembered many of them, but added new ones too, depicting the places he had been to so far and the saints and other spirits who had helped him along the way. There was an image of Notre Dame, and one of Saint Martial and San Nicola. Saint Martial stood with bread and a fish, while San Nicola was depicted with a bishop’s hat and staff. A noaide’s drum was his map of the universe as well as a record of the places and spirits he had met with. Aunt had packed him some alder bark with which to make a red ink, and Bávlos had obtained a writing quill from Girard. Now, at his leisure, he could carefully record his experiences. He only wished he could draw as well as Father Jens or others who knew how to read and write in the way of these lands.

After a time, Bávlos walked down the meadow to gather more firewood. Although the ground was wet, it was easy to find pieces that were old and dry and suitable for a fast, if not particularly long-lasting or hot, fire. As he proceeded with his eyes downcast, he heard a seagull’s cry.

“A seagull!” thought Bávlos. “That’s a welcome sound!” He had not heard a gull’s cry since leaving Gotland so many months ago. North of his father’s lands one met with gulls when nearing the northern sea. The gulls were indicators of the coastline and a sign that spring had come. Here it had to mean that he was still near the coast, perhaps only a couple of hours’ walk to the west. Perhaps there would be another sea to cross before he reached his goal. It was hard never knowing what Iesh intended: to travel and travel without an endpoint in mind. Back home, travel always had a purpose, it was always directed to a particular place. In this wandering existence he had taken up, Iesh offered no instructions, aside from the promise that he would say “Stop” when the time had come.

The seagull’s call came again and Bávlos looked upward. An old, bedraggled gull hung in the air above him, turning his head to get a better view. He looked hungry and expectant, like the gulls that idled overhead on the coastline whenever Bávlos and his father returned to shore with a plentiful catch.“Are you wanting a share?” asked Bávlos, smiling. The gull remained nearly stationary above. Bávlos walked back to his fire and took up the stringy intensines of the grouse. He swung these in the air, singing the joik for the northern bupmálas, the kind of gull he knew back home:

Na nanna na na,

Grating squawking, always hungry

Good friend my little fulmar.

As he pronounced the last line, Buore ustit bupmálachan, he let the intestines fly into the air. The gull dove avidly at them and caught them in his beak. He flew aside to find a place to land. A crow swept in from the side, however, snatching at the other end of the intestines and flying in the opposite direction. The birds pulled away from each other, tearing the tiny string of intestines into pieces, with a large chunk falling between the two. The seagull tilted its head backward rapidly and gulped down the morsel it had retained. Then it turned to retrieve the fallen piece. Two other crows had already descended upon it, however, and the larger of these had swallowed the remaining piece. With clear irritation, the seagull called in Bávlos’s direction.

“Don’t blame me, little friend! You’ve got to be more careful! Come, I have other scraps by the fire.” The gull seemed intent on getting everything he could from his new companion. And Bávlos was glad to have a new conversation partner, if only for a while.

After breakfast was completed, Bávlos returned to his trek. By midday, he could see a city rising in the distance, securely enclosed with a wall along a winding river. The spires and towers of the city were alternately bright and gloomy beneath shifting clouds. A pair of domes rose over the wall along with a tall tower of gleaming white. The road he was walking swung south toward the city. Something inside him told him that his way lay there. Within an hour, he had reached its gate. A guard stopped him and asked his business.

“Pilgrim,” said Bávlos, showing the shell he had received from the kind priest on the coast. The man nodded gruffly but pointed at the reindeer. “And the stag?” said he.

“Also a pilgrim,” said Bávlos. The man laughed and waved him on. The road Bávlos now found himself on seemed to lead through the city toward the great domes and tower he had seen from afar. They seemed well worth seeing, and Bávlos fully intended to proceed in their direction, but at that moment, the clouds that had been bearing down all morning suddenly released their rain in a torrent. Paving stones and rooftops rang with the sound of halestones. In the crash of rainwater so powerful that Bávlos could barely see in front him, he caught sight of a small chapel to his right, with a carved Notre Dame above the door. A small alleyway led behind the chapel to a little courtyard.

“In there,” said a voice. Bávlos complied. He led Nieiddash into a small piazza with a covered loggia and tied her to a post there. Then he walked up a small flight of stairs into the chapel, crossing himself as he entered. It was lighter inside and quieter than Bávlos had expected. None of the tumult of the rain seemed to be audible in this little space. Light streamed through several windows high in the front and side wall, and there was light coming from a large candelabra in the corner as well, where a man stood on a ladder, doing some sort of work on the wall. Bávlos stepped nearer to see. The man was painting. He stood with a palette in one hand and a brush in the other, applying paint to a wooden panel. He was painting the image of a tall, thin but muscular man, very white, very young, with flowing blond hair. Bávlos thought of Bengt Algotsson, King Magnus’s advisor so far away in Sweden. The most striking thing about the picture, however, was that the man was bristling with arrows: he had been shot through the wrists, through the chest, through the stomach, through the neck, and all the arrows remained firmly wedged in place. Two entered his skull and at least six afflicted his legs. One had pierced his loincloth and Bávlos could see blood dripping from the wound. All in all, he looked in terrible shape. Yet despite this situation, the man looked perfectly calm, almost bored. A group of frustrated archers stood beside him, arguing with each other in their evident frustration at their inability to finish him off. Bávlos stared at the picture intently.

“Good day, sir Pilgrim,” said the painter, looking over his shoulder.

“Good day,” said Bávlos.

“Like it? asked the painter, fishing for a compliment.

“Yes, very much,” said Bávlos. “But who is this man, and why have these others shot him?”

“San Sebastiano, don’t you know!” chuckled the painter. “Became a pincushion for our Lord!” He suddenly seemed to feel a twinge of guilt for his irreverence, cleared his throat and crossed himself. “A great saint,” he said, “a holy saint. Helps with all sorts of disease. A great favorite with the ladies.”

“You are a painter?” asked Bávlos.

“I am a painter,” said the man. “Buonamico Buffalmacco; perhaps you’ve heard the name?”

Buonamico Buffalmacco. The name sounded so familiar. It was like bupmálachan but different. And the man’s first name, Buonamico, meant “good friend” in Italian. Somehow this was the buore ustit bupmálachan of his joik, turned to human flesh. He even had the same expectant look! At once Bávlos realized that the man was expecting a reply, so he blurted,

“No, no, no. I am not from here. My name is Bávlos.” Buonamico listened to the stranger’s accent. Where had he heard that voice before? And where had he seen those eyes before: so piercing, so blue?

“You’re not from here, then?” said Buonamico. “Are you certain we haven’t met before?”

“Not unless you were flying this morning,” smiled Bávlos, looking intently at the older man’s face to watch for any signs of reaction. The man visibly stiffened.

“Flying? Ha!” You’re jesting good sir!” Buonamico tried to laugh the matter off in this way, avoiding the stranger’s continued gaze. “Lunch time, I think,” he said briskly. “Angelo, my boy! Pack us up for the day!”

“Angelo?” asked Bávlos, looking around. The church looked empty to him.

“Angelo? Angelo! “ called the man irritably, “Where the, where the blazes has that boy gotten to?” he growled.

“I can help you clean up,” said Bávlos.

“That would be kind,” said Buonamico, his voice softening, “That would be very kind.”

“So you are a pilgrim?” said Buonamico, as the two men finished clearing away the paints and brushes. “A pilgrim to Pisa, or are you headed for Rome?”

“What city did you say?” asked Bávlos, excited.

“You mean Pisa?” asked the painter, surprised. “Pisa man! You have reached the city of the Pisani, did you not know? Pisani!”

“Bisan,” thought Bávlos, “so this is it at last! The place where my journey ends.” Aloud he said: “I have indeed come to Pisa and I am glad of it indeed.”

“Good sir,” said the painter suddenly, “Would you care to dine with me? There’s no telling what my prattling housekeeper has prepared and whether that roguish Angelo has not already wolfed most of it down his gullet, but nonetheless, if there’s anything left to be found, I would gladly share it with you if you please!”

“Certainly,” said Bávlos. It occurred to him that this was the first time anyone had offered him a meal since his visit with the priest on the coast on Christmas morn.

They stepped out of the chapel into the narrow lane. “Come along then,” said the man briskly.

“Wait!” said Bávlos, “I need to fetch my deer.” He stepped quickly down a side alley and came back leading Nieiddash. Buonamico stared at the strange beast—smaller than a pony, with wide, tall antlers and clicking splayed hooves.

“Well I never!” he cried. “Bávlos, you must be from quite a distance away!”

“Quite a distance!” laughed Bávlos. The men began to walk, Nieiddash following docilely behind. People stared and chattered at the sight.

“Mind you, I’ve seen even stranger pets,” said the painter. “A bishop I worked for once in Vescondo. He had an ape!”

“An ape?” said Bávlos.

“You know, “ said Buonamico, sensing his companion’s confusion, “Little animal, looks like a furry little man.” Bávlos’s brow furrowed at the description: he knew the animal only too well. “Oh, yes, one of those.”

“That’s right exactly,” said the painter. “Well, as I was saying, I was working on a Baptism of Christ. Devilish hard thing, those baptisms—you’ve got to show Jesus with his feet in the water—very tricky to make it look realistic, I must say. Why it’s almost that feast day in just a few days!”

“Ah,” said Bávlos. A painting of the dousing. It must have been cold for Iesh to be doused in early January.

“Well,” continued the painter, growing animated, “All day long I slaved at that painting, sweat pouring from my brow, barely stopping to wet my whistle and bolt down a scrap or two of meager bread before returning to my work. That ape watched my every move. He never took his eyes off me. It was like painting a work for a bunch of busybody nuns: never stop watching you all day long.” The mention of the nuns seemed to head Buonamico’s story in a new direction, but he caught hold of it again and returned to his original story. “Well anyway, when I left the work on Saturday it was so late and so dim in the church that I decided to leave my equipment in place until I could return to finish the work up on Monday morning. I was pleased with the painting, I must say, it was inspired!”

“Ah,” said Bávlos. He didn’t really see what this tale had to do with apes, but it had been entertaining. He laughed and nodded.

“Wait, the story’s not over yet!” cried Buonamico with a guffaw, “It’s just begun! You see, when I got back on Monday, what do you suppose I found?”

“What?” asked Bávlos excited. “My painting defaced!”

“Defaced?” asked Bávlos confused by the word. “Defaced man! In the place of the Savior’s serene countenance there was now a big bug-eyed monster with a mouth about a foot wide! And Giovanni Battista’s nose was now at least two feet long and bent down to the water! It looked demonic, man, purely demonic!”

“What did you do?” asked Bávlos.

“Well I spent the day trying to put it right again!” he said. “It was terrible work! The paints were dry and they couldn’t just be scraped off. I had to paint them out and redo the faces of both the main figures of the painting, along with a whole sweep of background: beautiful brown rocks that looked really desert-like I must say.”

“Well, then it was okay after that?” asked Bávlos.

“No!” cried the painter. “The very next night, someone vandalized the painting again! Now the Baptist’s hands were scribbled out in red, like they were dropping blood on the Savior. The pool was full of blood too, and even the Holy Spirit, in the form of the dove about Jesus’s head was smeared in the gore! Can you imagine? It looked like some heretical tract! I was at my wit’s end!”

“What did you do then?” Bávlos asked. “Well, I complained to the bishop!” said Buonamico proudly. “I marched up to him and complained! I said, ‘I can’t work in a place where my holy efforts to portray our Lord’s sacred baptism are so reviled and besmirched! There is a heretic at work in this church, your Excellency, and I won’t stay a minute longer!”

“A heretic?” asked Bávlos.

“That’s what you call just about anyone who’s got a quarrel with one of the clergy or anything else connected with the Church,” said Buonamico nodding, “It’s a powerful insult.”

“Oh,” said Bávlos.

“So, anyway,” Buonamico continued, “The bishop tried to calm me down. ‘Buonamico,’ he said, ‘You’re a great painter, a fine painter, and I don’t want to lose your work in my church. Repair the painting one more time and I will set an all-night guard on it till you’ve got it done. The villain who defaced that painting will be behind bars in no time, you can count on that!’”

“My goodness,” said Bávlos, “You must be a very famous painter indeed.” Bávlos thought of Bishop Hemming; it was hard to imagine him caring much for anyone else but himself.

“Well,” said Buonamico, chuckling with pride, “It would be accurate to say that I am well known, yes. At any rate, back to my story: I went back to work on the painting and got it done that very afternoon. The bishop set his guard and we all waited to see if the villain would attempt his perfidy again. And what do you think we discovered?”

“The ape?” asked Bávlos, smiling.

“You got it! It was that blasted ape! He had found a way out of his cage each night, had climbed up to the painting and had tried his best to improve it, monkey style! Of course, the bishop thought the whole matter hilarious and I had to act like I did too. It would have been bad for business to tell the bishop what I really thought of his little pet and his pranks! So I said instead, ‘Well, it looks like you have a painter of your own, so if you don’t mind, I’ll just head back to Firenze!’”

“Firenze?” asked Bávlos.

“Yes, Firenze,” said his companion. “that’s the city where I was born and where I am headed back after finishing this work here in Pisa, unless some other commissions come my way around here. Which reminds me: what city are you from? Antwerp perhaps?”

“I don’t come from any city,” said Bávlos thoughtfully. “I come from my father’s lands.”

“Oh, nobility, eh?” said Buonamico. “And where are your father’s lands?”

“They lie far, far to the north,” said Bávlos sighing. “It has taken me months to reach this place.”

“North of Antwerp then?” said Buonamico, “North even of Lübeck?”

“Lübeck, yes: I passed through there on my journey,” said the Bávlos excitedly, “Across the sea to the west from there, and then back across the sea to the east again, to a place called Ĺbo in Finland, and then almost a full month’s walk north of there. I don’t know what place you’d call it in your language.”

“A month’s walk north of Lübeck?” gasped Buonamico. “Is it possible? I had no idea there were lands so distant from the world! We must ask Master Simone back in Firenze about it sometime. He is very knowledgeable in geography, or at least he is always claiming that he is. He’ll be able to tell us where you’re from! In the meantime, here’s my home. Let’s eat!” The men had reached a small doorway on a rather narrow street. It was built of small stones plastered together with some hard muddy substance. There was one tiny window at the same level as Bávlos’s head and a large wooden door with a decorated handle. Above the door was a sign that depicted a snail.

“My friend Calandrino inspired that sign,” chuckled Buonamico. “He once told me that we painters are like snails: we spend our days daubing walls with slime! Anyway, in we go!” As the door swung open, a panicked boy of about fourteen leaped from his seat and sprang out the back door.

“Angelo!” cried the painter testily, “Angelo you rascal! I’ll deal with you soon enough.” Turning to Bávlos he softened his tone and said, “Pray, good Sir Bávlos, sit down and let us dine. Signora Bertoli, I hope you’ve made enough for my friend as well.”

“Oh there’s enough!” the old woman cackled. “Plenty! No one cooks like old Signora Bertoli! And so frugal too! A nice stew: started it three days ago! Lots of good beans, good cabbage, old bread! Eat, eat, good sir!” Bávlos gratefully did so. The stew tasted warm and filling. Buonamico poured him some wine.

“So how are you managing this journey?” the painter asked.

“Managing?”

“What are you doing for money, I mean,” asked the painter.

“Oh, money,” said Bávlos. “Easy. Every so often I sell a pelt or two and that brings in some coin.”

“A pelt?” said Buonamico, his eyes widening, “Are you a dealer in fur?”

“No,” said Bávlos, “I’m a trapper. Actually, these are my uncle’s pelts from his trapping last winter. He sent them along with me in case I shouldn’t find enough to eat by foraging or hunting.”

“And what sort of furs are they?” asked the painter.

“Fine furs,” said Bávlos proudly, “soft and warm: some deer pelts, but also ermine and martin, and some arctic fox.” Bávlos said the names in French, but Buonamico seemed to understand them readily enough. “Look, I have them here in my pack!” He undid his pack and pulled out the furs. Buonamico’s eyes grew wide. “And do you know,” said Bávlos, “these furs seem to fetch more money the further south I come, even though they can hardly be of much use around here, where it never gets too cold, as far as I can tell.”

“Ha!” laughed the painter, now more jovial than ever, “Right you are! Why these are the stuff of royal costumes in Italy! I can bring you to a furrier here in town who will pay you a fistful of fiorini for these furs!”

“That would be very helpful,” said Bávlos. “I have not known where to trade these since coming to this region. The last time I traded any was in Paris.” Buonamico treated his friend to some more stew and another large stoup of wine. Bávlos found both delightful. The wine was particularly alluring: it was unlike any drink he had ever had before, although he recognized it as an Italian version of the drink he had often shared with his holy friends in France. This Tuscan version of the drink seemed to warm him from the inside, making everything seem happy, amusing. Before long, Bávlos felt better than he had felt for many months.

After lunch, the men took some of the furs to a furrier whom Buonamico knew and received an ample measure of coins in return. Bávlos held back some of his uncle’s merchandise in case he needed money again sometime in the future.

“It’ll be a long time before you go through all this money,” laughed Buonamico. “Come, let’s go into the tavern nearby here to celebrate the deal!”