Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348

a free multimedia novel by

Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison

|

Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348 a free multimedia novel by Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison |

|

|

|

|  |

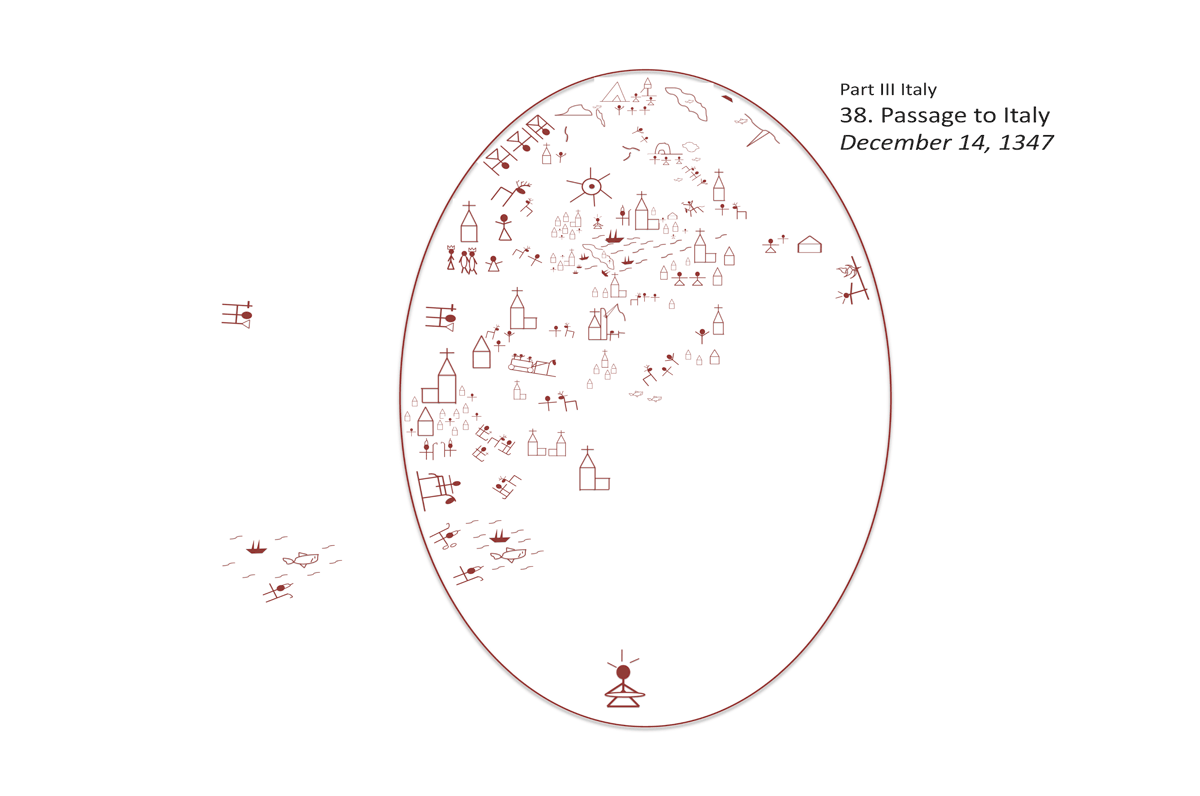

Part III. Italy

38. Passage to Italy (December 14, 1347)

“What shall we do with you,” they asked,“that the sea may quiet down for us?”For the sea was growing more and more turbulent.Jonah said to them, “Pick me up and throw meinto the sea, that it may quiet down for you.”

“Guard the wind-knots.” His grandfather’s voice spoke to him aboard the ship. Bávlos was startled. Who would want to steal his knots in this place of ample wind? And, even more to the point, who among these strangers would even know about wind-knots? Bávlos kept them stored in his pack, deep at its bottom. Stiff in dried blood, the leather band was dark and plain. It held no immediate allure, like the pelts that any thinking man would desire. “Guard the wind-knots” was all his grandfather would say. Iesh was silent on the matter.

Somehow, through a series of events that struck Bávlos as wondrous and improbable, he had found passage on a ship headed toward Rome. The countryside between Limoges and the coast had sped by, as Bávlos, now no longer accompanied by novice skiers, had found his accustomed stride and journeyed at a remarkable speed. Nieiddash had trotted contendedly and with ease on the light and powdery snow that had remained beneath their feet almost down to the coast itself. Obedient to the orders of the future pope, Bávlos and Nieiddash had stayed aloof from all villages and towns throughout the journey, living off the ample provisions Guillaume had procured for Bávlos at the monastery refectory and supplementing these by hunting and fishing. The fish no longer took bait as readily as in the warmer seasons, but remained sluggish and barely visible in the quiet waters of ponds and streams. But Bávlos, ever resourceful, had been able to spear enough fish to give him some variety in his meals. On occasion, he had even stooped to eating rabbit, a food unthinkable and shameful in his own lands. Nieiddash had taken to supplementing her scrounging for ground plants with bark and moss from trees and had become expert in catching small mice to eat as well. It seemed to Bávlos that she was intent on eating now, building the body of the calf she carried inside.

At the coast, Bávlos had managed to exchange two of his finest furs for passage on a ship headed for Rome. The ship itself was larger and more cumbersome than the light, swift sloops he had sailed in across the northern sea. It required a sizeable crew and consisted of numerous levels below deck for various supplies and purposes. There was a large room just under the top deck for Nieiddash as well as a number of cows, chickens and pigs. The other animals were there mostly to serve as meat along the way, Bávlos suspected, and they were not treated with any particular regard or affection. There was little room to move about in the animals’ hold, and Bávlos seemed the only one who cared to keep the space mucked out. It was a constant effort. Nieiddash was greatly bothered by the situation and made her annoyance clear through pointed kicks at the other animals and a perturbed glare and grunt at Bávlos whenever he appeared.

The captain and the crew of the ship did not sound French to Bávlos. They said many of the same words, but with more of a pulsation to the voice and with short bright sounds at the end of each word rather than the lingering pauses Bávlos had come to recognize in the north. Bávlos suspected that these were speakers of Oc, the other language that Jacques had said bordered Oďl to the south. Sometimes, when Bávlos was listening only casually to this new language, he could have sworn that they were speaking Sámi. But, of course, they weren’t; and with a little practice and diligent listening, Bávlos began to recognize words he knew from the north of France, pronounced in a different manner and often with a somewhat different meaning.

The captain had been very suspicious about taking Bávlos on board, questioning him closely about where he had stayed and whether he knew of the great sickness that had beset the region. In the end, it was the richness of Bávlos’s pelts that had convinced him to grant the stranger passage. The captain also had a strange animal that he kept in his cabin: a small squirrel-like beast with a long tail and feet and hands almost like a man’s. This little animals was called a monin. Bávlos had never seen such a creature: he seemed almost as smart as a bear, yet he could perch on the captain’s shoulder and pick food from his plate. He was a friendly and attentive to all who came near, although habitually prone to biting. The captain called him Amic, which, Bávlos eventually learned also meant “friend.”

Even though it was December, the sea was still warm, at least to Bávlos’s touch, and relatively calm. The sky was low and broody with clouds, but the sun continued to shine through on occasion and colored the water a vivid blue. The ship hugged the coastline closely, in its southward journey, tacking back and forth in sight of the shore in the brisk December wind. It was dangerous to stay too near the coast, the captain said, but also dangerous to put out too far from shore in this season.

Bávlos was amazed by what was possible here in winter. “In my land,” he told the captain, “the sun is barely seen for several months, and the sea is far too stormy to venture upon.”

“You live in the God-forsaken reaches of the north, good pilgrim,” said the captain. “Here we are blessed with kinder waters, kinder weather, and of course, the help of great saints like San Nicola to keep us ever safe.”

“San Nicola,” said Bávlos, “Who is he?”

“Do you mean to say that you have never heard of San Nicola?!” gasped the captain. “I had no idea that Scotia was so backward.” Bávlos thought it wise not to discuss his pagan background with a sailor or to inquire further about this place called Scotia. In his experience, sailors had always been highly suspicious people, always afraid of bringing bad luck upon themselves through various indiscretions. He knew that many strangers in the north would not let a Sámi even step foot aboard their boats, and he remembered well his difficulties there with the captain who took him to Stockholm and the various unwilling captains who refused to take him from Kalmar.

Thinking quickly, he said: “Tell me about San Nicola; perhaps I have heard the tales and forgotten them.”

“Well,” said the captain, “Nothing would give me greater pleasure.” And so he began his tale.

“In the land of Byzantium, far to the east of here, there lived a noble and wealthy man named Epifano whose wife was called Giovanna. This Epifano and Giovanna had lived many years together but they had never had a child. At last, in his mercy, God sent them a son, whom they named Nicola, which means “victory” in the Greek tongue.“Now this Nicola was unlike any other baby the couple had ever seen. He only needed to be nursed twice a week, on a Wednesday and a Friday, and this made things much easier for his poor mother, who was getting on in years.“

Bávlos thought this tale most wondrous. How could an infant only eat twice a week? And how had Iesh made this couple fertile after so many years without children? It was an intriguing tale, one that hinted at powers of Iesh that Bávlos had never guessed before. The captain continued:

“As he grew, this little Nicola became very holy and loved to go church. He never wanted to play with the other children but stayed apart and prayed. And when he came of age, his parents died, leaving him a great fortune which he determined to use to give honor to God.”

“So Nicola had been reclusive,” thought Bávlos. He recognized the tendency in himself. “All who are called to become priests of Iesh have such traits,” he thought to himself. “Let us hear what became of this man.”

“Well, there was a man in the neighborhood who had three daughters,” the captain continued. Bávlos was surprised by the shift in the tale. Would Nicola prove the marrying kind after all?

“This man was a nobleman but very poor, so he didn’t have the money to pay for the daughters’ dowries. When the oldest one came of age, the poor father thought he would have to let her become a prostitute, because there was no one to marry her without a dowry.”

“A prostitute?” asked Bávlos, “One who sleeps with men for money?”

“Indeed the very same,” said the captain, winking. Bávlos thought it very strange that people here in the south had only two options for their women: that they should either have the wealth for a bride’s payment or have to sleep with men for money. In his homeland, women needed a healthy stock of reindeer to marry well, but poorer women always found husbands of one sort or another. And no man simply became resigned to letting his daughter sleep with strangers, even if she was a girl of a wild nature who wanted it that way.

“The holy Nicola got wind of the problem,” said the captain.

“Did he marry her?” asked Bávlos, excited.

“No,” said the captain, “He came into the neighbor’s house at night when none were looking and left a great pile of gold there as a dowry for the girl. When the man woke up that morning, he found the pile of money and gave thanks to God. He wanted to find out who had helped him, but he had no clue.

“Years went by and the second daughter was coming of age. Again, the father thought that she would have to become a prostitute, but again, out of nowhere, a pile of gold appeared one night. All the town was talking about this miracle. Finally, the youngest daughter came of age. This time, the man was hoping the miracle would happen again and he stayed awake all night. Toward morning he saw a bag of gold come falling down the chimney! He sprang out of bed and saw a man running away. He pursued that man and eventually caught up to him. It was his neighbor, the holy Nicola. ‘Why have you helped me?’ the old man asked. ‘Because treasures are meant to be shared,’ said the saint. The man knelt down and wanted to kiss the saint’s feet, but the holy Nicola would not allow it. ‘Get up,’ he said, ‘and be generous to others, that is all I ask.’”

“This Nicola certainly does seem like a kind man,” thought Bávlos. “He had given of what he had freely, not even wanting a word of thanks.”

“Later on, this Nicola grew to manhood and became a priest.”

“Ahaa,” said Bávlos aloud. Now the story was making more sense. “Meanwhile the bishop of Mirea died and the city was in need of someone to replace him. All the bishops of the region gathered at the cathedral to pray and select a new bishop for the city. There was a holy aged bishop among them, and this bishop had a dream. He heard a voice that said to him, ‘Go to the doors of the cathedral at matins and watch for who comes in. The first man who enters will have the name Nicola. That is the one who should be bishop.’ Well, the bishops did as the great bishop advised. They all went to the doors of the cathedral and waited. Along about matins, a humble priest arrived and entered through the door. ‘Holy priest,’ the great bishop said, ‘What is your name?’ ‘I am called Nicola,’ said the priest. At once they offered him the bishop’s seat and the holy Nicola, humble though he was, accepted the office. But he was always humble, and fasted often and stayed away from women. He was said to show great kindness to those in need but be cruel to those who needed correcting.”

“This bishop sounds very worthy,” said Bávlos, comparing him in his mind to the bishops he had met so far, “but why do you call upon him especially upon the sea?”

“Well,” said the captain, “It was like this. There was a ship of merchants headed toward Mirea and they ran into a storm. The winds were high and the rain fell in sheets and the waves rose up taller than the mast. The men thought they were goners. Then one of them, who had heard about Bishop Nicola, called out into the wind: ‘Bishop Nicola! If you are really as good and holy as men say, come help us now!’ At once they saw a man in a bishop’s vestments above them in the sky. This vision called down to them: ‘What is it? You called me?’ ‘Help us!’ they cried. The winds and the rain stopped immediately and the waves calmed at once. The ship sailed on to Mirea and when they arrived at the port, the men of the ship did not tarry but hurried to the cathedral. As they got there they saw the bishop, and he was the very likeness of the vision they had seen in the sky. They thanked him loudly for what he had done, falling down at his feet and crying, but he just waved his hand and said, ‘Thank God and your faith, not me.’”

“I can see why men pray to this San Nicola then,” said Bávlos. “Did he ever do anything else for sailors?”

“Yes,” said the captain, “he did. There was a time that the holy bishop’s land was suffering from a famine. Nothing would grow and the people had nothing to eat or plant. In the meantime, there were some merchants who arrived from Genova with cargoes laiden with grain.‘Share some of that with the poor of this city,’ said the bishop.‘Sir, we dare not,’ was their reply. ‘This grain is already bought and paid for by the Emperor of Alexandria, and if we arrive with any less than he expects, we will be tortured and put in prison for sure.’ ‘Fear not,’ said the bishop. ‘Do as I say, and God will make sure that your load isn’t light when you arrive.’ So they shared some of their grain with the people of the city and sailed on to Alexandria. And when they got there, they found that their grain holds were as laiden with wheat as when they had left. So the emperor was happy and the people of Mirea were saved from starvation. And because of this, merchants always pray to San Nicola, because there is many a cargo that arrives at port lighter than when it left.”

“Well,” thought Bávlos, “Christians are clever beings. They have spirit helpers for specific needs, just as we do. This Nicola seems to have a way with the Wind-man and to help out with merchant’s loads as well. He seems a useful friend for people like this sailor.”

“Another thing that was great about San Nicola was that he protected people from pagans.” Said the captain, looking out at the horizon.

“Ah,” said Bávlos a little uneasily, “were pagans a threat?”

“Of course they were!” cried the captain. “Let me tell you what happened. In that land where Mirea lay the country people continued to believe in the cursed Diana, a demoness of the forest. This Diana demanded sacrifices under a sacred tree out in the countryside and the people were too afraid to refuse. Well the holy bishop heard about it and he sent soldiers to the region to cut down the tree and force the people to abandon their evil ways. The demon Diana was furious and she decided to get even. So she made an evil oil that had magic properties: when it came in contact with water, instead of burning less, it burned hotter still! She turned herself into the form of a little old woman and put herself in a little boat and headed out to sea. And there she came to a boat of pilgrims on their way to visit the holy bishop.‘Please,’ she said, ‘I cannot make it to Mirea myself. But I have this oil to offer at the church. Please anoint the walls of the church with this oil in my memory.’ The pilgrims willingly took that oil and the woman sailed away. They were going to do exactly as the woman had said. But then they met with another ship, and on it was one who looked like the holy Nicola. And this man said to them: ‘You have met with the evil Diana. Throw whatever it is she gave you overboard at once!’ Well, they cast the oil into the sea and at once the sea caught flame! They watched it burn long after they had sailed away. And the people cried out: ‘Praised be holy Nicola, who saves us from the wiles of the devil and the dangers of the sea!’”

“Ah,” said Bávlos nodding. He was unnerved by this tale. The captain seemed to be winding down, however.“Long after this the pagan Saracens destroyed the city of Mirea and there was none to keep the holy saint’s relics safe or do them reverence. So a fellowship of knights came from the city of Bari here in Italy, and they sought out the holy bishop’s relics and brought them to Bari, where they rest today. And that is why it is always lucky to have a man from Bari on board one’s boat. We don’t have one of those,” said the captain, slapping his passenger on the back, “but a Scotsman isn’t so bad either.” Bávlos laughed and nodded. He felt very uneasy. He had been, until recently, a pagan himself, and certainly he had made lots of sacrifices to Saráhkká, who seemed somewhat like this Diana of the story, only much kinder, much more like Notre Dame. Sacrifices beneath trees were certainly something he was familiar with, and he could well imagine a Sieidi planning some evil for a man who had the impudence to cut down a sacred tree.

“I must go and check on the livestock,” said Bávlos, excusing himself. When Bávlos returned to his cabin that evening, he was shocked at what he found. His pack had been opened and its contents flung across the floor. At first, Bávlos suspected thieves, but they had left his pelts untouched. He carefully gathered these up and stuffed them back in his pack. Everything seemed to be there, everything but the wind-knots. The wind-knots were gone. When Bávlos had received his knots from Elle, he had promised to take good care of them and possibly even return them if they were not needed. He had diligently guarded them from water or light for many, many months. He didn’t know when he would be back on his father’s lands to acquire more, and he remembered that Iesh had told him to bring wind-knots along on his travels. Now they were gone, and on the sea as well. If someone ignorant had gotten ahold of these, it could bring great peril to the ship. Bávlos hurried onto the deck to seek out the captain. He was leaning against the ship rail and laughing pointing up at the ship’s main mast. Bávlos’s eyes followed the captain’s gaze upwards to see what was so amusing. There, on the top of the mainsail sat the captain’s mischievous Amic, with Bávlos’s wind-knots in his hand! Bávlos was stunned. What should he do? If the little beast began to undo the knots, all could be lost. But how to retrieve the knots without calling attention to their magic, without arousing the captain’s suspicions? Pagans were not regarded kindly on this boat, Bávlos sensed, and it was dark now and, as far as he could tell, a long way to shore.

“Captain,” he said tentatively, “I think your Amic has a kerchief of mine that I received from my cousin. It is a keepsake that is dear to me.”

“Is it?” said the captain smiling. “Oh, I’m sorry, sir pilgrim. Amic is a troublesome little fellow. He is always stealing things. I will try to coax him down.” The captain whistled and called for his pet, but the beast remained on the high mast, fingering the knotted cloth and chattering excitedly. Bávlos could tell that the animal was enjoying chewing the leather, savoring no doubt the taste of blood it contained. At length, he started to undo one of the knots.

“No!” cried Bávlos, “Don’t let him do it! He is letting the knot come undone!”

“I’m sorry, sir pilgrim,” said the captain. “Such things fascinate the little beast.”

“But, but—“ Bávlos closed his mouth. There was nothing he could say. As Amic finished untying the knot, the sky began to turn blustery. A strong wind burst upon the ship from northward and pushed the boat briskly on its way.

“Hey ho!” cried the captain, “Where did that wind come from? I thought it was going to be calm tonight!” Bávlos shrugged his shoulders. Amic screeched with excitement. “Come down from there!” called the captain. But Amic only climbed higher, excited by the wind. The captain was now busy giving orders, adjusting the sails to the new situation and having loose lines tied down.

“Better get downstairs,” he said to Bávlos, “the weather seems to be rising.” But Bávlos could not go downstairs. He stared at the animal, willing it with all his might to return. The little beast seemed to sense his thoughts, turned straight toward him, and peed. In the strong wind and great distance, none of the urine reached the deck.

“What are you doing now, you little devil?” laughed the captain, “Come down here at once!” But Amic only chattered further and began to untie the second knot.

“No!” cried Bávlos, now in a panic, “Don’t let him untie that! Please!”

“Untie it? Say, what is this all about?” said the captain, with a change of tone. No doubt he had heard about northern wind wizards who kept breezes stored in knots. Just as he was turning to face Bávlos though, the little animal had managed to untie the second knot. Immediately, the weather turned worse than before, battering the ship like a wave and sending it careening to its side. Bávlos had to grip tight to keep from being swept overboard. “Hey!” cried the captain, now as excited as Bávlos, “this storm is turning rough! Get below at once, sir pilgrim!”

“I can’t,” said Bávlos plaintively, “I can’t without that kerchief.”

“Without that kerchief?” said the captain. Suddenly he seemed to put two and two together. “Say, those knots—“

“Wind-knots,” said Bávlos, hanging his head.

“Heaven help us!” muttered the captain. “What are we to do? How long do they go on once opened?”

“No telling,” said Bávlos. “It depends on the woman who did the knotting.”

“Sorcery!” cried the captain menacingly, “And on my boat! Pilgrim, what do you have to say for yourself?!”

“Nothing,” said Bávlos, “Only don’t let that animal of yours untie the last knot or we are done for I’m sure!”

“Amic! Now! Down here at once!” cried the captain. It was unclear that the little beast could even hear his master’s words at this point, the storm was blowing so hard. “Pilgrim,” he said, “What are we to do?”

“Should we appeal to San Nicola?” said Bávlos timidly.

“Good idea,” said the captain, “Do!”

“Me?” thought Bávlos, “Surely the captain should do this himself! San Nicola is likely to be pretty angry with me.” Nonetheless, he breathed deeply, closed his eyes, spread his hands out wide and prayed: “Kind San Nicola, guardian of sailors and ships, protect us from these winds! Bring us to safety!” The winds continued unabated. Bávlos was dashed to the deck by the lurch of the ship. He heard a response:

“Do as Jonah did, my lad, and the ship shall be saved.”

“Jonah?” said Bávlos aloud, “Do as Jonah did?” He had never heard the tale of any Jonah, nor was he prepared for what the captain did next.

“Jonah!” he cried, “Shall we do the Jonah with you? All right then, man. Gather your things together and get back up here at once.” Bávlos could tell what this meant. He was to be sacrificed to the winds, cast overboard to appease an angry deity. It had not been his fault that the little beast untied the knots, but he had brought the danger on board nonetheless. And now he must pay with his life.

“San Nicola,” he said to himself, “Take care of me. I have done what I did at the behest of Iesh and I meant no harm.”

Down in the hold the animals were panicking. Bávlos had difficulty extracting Nieiddash from the fray. He grabbed her harness and led her struggling up to the deck. Her eyes flashed with panic. The sky was dark and menacing, with winds lashing the deck and waves bursting overboard. Bávlos stood with his reindeer and his pack, bound up in the gieres. In this context it looked like a little boat, and Bávlos remembered how folk used to make offerings to the wind by tying a gieres up in a tree. Now he was to be an offering himself.

“I am ready,” he said. For all his shouting and fury, the captain seemed hesitant now to let his passenger die.

“Are you sure you want to do this?” he asked, shouting over the gale.

“What must be must be,” said Bávlos. “Take care to get that kerchief away from your little beast and keep the knot on it safe unless you want another wind someday. It would be best to untie it in some inland area where nothing can be sunk.”

“I’ll take care of that knot,” said the captain. Something told him that the captain would save it for use on the sea. Wind-knots were valuable commodities, Bávlos knew, worth a load of pelts to a merchant in need. With a deep sigh and a silent word to Iesh, Bávlos pushed his panicked reindeer overboard and jumped after her himself, the gieres tied to his arm.