Part III. Italy

Chapter 38. Passage to Italy [December 14, 1347]

Cultural Explanations

|

Part III. Italy Chapter 38. Passage to Italy [December 14, 1347] Cultural Explanations |

|

|

In this chapter Bávlos finds himself in a perilous situation after taking passage in a ship headed for Italy. | ||||

| Biegga-olmmái (Wind-Man), ship, great fish, St. Nicholas |

In this chapter, Bávlos uses his skis and sled to make a hasty journey to the southern coast. Two routes were available to medieval French headed toward Rome. They could take a land route across the Swiss Alps—not a workable option in December—or they could travel by foot or boat along the Riviera and Italian coast. Bávlos knows that he has to cross two seas, so he chooses the water route.

The distance from Limoges to the Mediterranean coast is about two hundred miles. A good skier can cover about eight miles per hour. Given the fact that an avid skier or walker might easily keep going for six hours per day, that would mean that Bávlos could reach the coast in four to five days. (Charles Dickens regularly walked six hours per day, ranging out of London far into the surrounding countryside.) So, after a very leisurely period of travel with Jacques and then with Girard and Guillaume, Bávlos is now moving at an energetic clip.

In the person of the captain, Bávlos meets with Occitan, the language of southern France. Bávlos is not sure what language he is hearing but manages to communicate using his skills in French. Undoubtedly, the captain is adjusting his speech to ensure that Bávlos can comprehend him. In the medieval period, French people spoke across the French/Occitan linguistic boundary readily, since both languages played important roles in the cultural and economic life of the country. The eventual triumph of French as the sole language of France occurred after the medieval period, and was never fully realized in the south, where Occitan remains a part of daily communication. The words monin and amic mean "monkey" and "friend."

If you can't remember when or where Bávlos got his wind knot, jump back to Chapter 6, or the Cultural Explanations page for that chapter. Bávlos associates the winds that it produces with the Sámi god Biegga-olmmái ("Wind Man"), who was frequently depicted on Sámi drum heads. Wind Man usually carries two shovels, one whole, one broken and was seen as a god who could bring either helpful winds or storms. Bávlos includes an image of Wind Man on his drum in connection with this adventure.

|

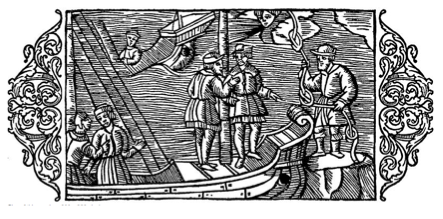

| Wind Knots for Sale. Italian Illustration of Olaus Magnus's Historia de Gentibus Septentrionalibus (1555); image courtesy Wikimedia Commons, |

Olaus Magnus's description of Sámi wind knots is accompanied by the above engraving that gives an inkling of what a Mediterranean ship of the day looked like. A ship model dating from the mid-1400s was displayed for centuries in a chapel in or near Mataró on the coast of Catalonia. The model eventually wound up in the Maritime Museum of Rotterdam. Ship models were important devices for planning and building ships. They could also be placed in churches as a prayer of thanksgiving or as a petition for safety at sea. Ship models sometimes survive in European churches but generally were removed in post-medieval remodellings, particularly as economies shifted away from sea-based trade. You can see such a ship model in the nave of the oldest church in the Province of Québec, Notre Dame des Victoires.

|

| The Mataró ship model, now housed in the Maritime Museum Rotterdam. Image by Joop Anker, courtesy Wikimedia Nederland Creative Commons |

Bávlos hears about the miracles of San Nicola, St. Nicholas. Although modern people tend to think of St. Nicholas in connection with Christmas, in the medieval era he was particularly associated with sailing and merchants. The miracles recounted here were widespread during the fourteenth century, appearing in much the form that they are presented in this chapter in Jacobus de Voragine's Golden Legend (Legenda Aurea), a compilation of saints' lives completed c. 1260.