Chapter 6. Getting Doused.

Cultural Explanations

|

Chapter 6. Getting Doused. Cultural Explanations |

|

|

|

| In this chapter, Bávlos begins to learn the central beliefs of Christianity, particularly the story of the Crucifixion. In Finnish, the Latin word Christus was borrowed as Risti, and came to mean both "Christ" and the "cross." This duality of meaning causes some confusion to Bávlos as he tries to puzzle out the sacred narrative from Pekka's muddled rendering. The story is perplexing to Bávlos also because it is clear that the powerful Iesh of the strangers is a victim, a being who has been treated with unsurpassed cruelty and disrespect by the very people who follow him. Given the reverence which Sámi accorded their sieiddit, this aspect of the new religion seems confusing indeed. |  |

||||

|

The chapter also depicts Bávlos's visit to his paternal uncle and his family at their home near the present-day city of Sodankylä, Finland. This site, at the confluence of two rivers, was an important trading site for many centuries, and Uncle seems to be prospering in this locale. A man's father's ulder brother was a particularly important relation for Sámi, and Bávlos knows that he can rely on his uncle for almost anything. Uncle and Aunt provide Bávlos with furs (a prized commodity throughout the medieval period), food provisions, a young reindeer, and a set of wind knots. Reindeer were kept in small herds during the medieval era and were much tamer than modern Sámi reindeer. Nieidash ("maiden") is particularly friendly because she has been reared by hand after her mother abandoned her. Reindeer could often abandon their calves if they were startled by dogs or frightening sounds soon after giving birth. Image courtesy Sámitour website |

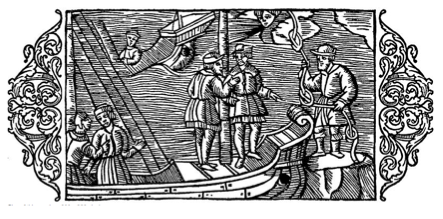

Wind knots are a mysterious detail in this chapter that play a role much later in the novel. The Sámi poet Anders Fjellner writes of a daughter of the sun who took wind knots with her into her marriage with the ancestor of the Sámi. These knots, soaked in menstrual blood, had the capacity to unleash powerful winds when these were needed for navigation. Throughout the later medieval period and after, European sailors' lore creditedthe Sámi with the power to harness and unleash winds when needed. These were stored as knots, which could be stored, sold, and traded. The last Catholic archbishop of medieval Sweden, Olaus Magnus, writes of Sámi wind knows in his Historia de Gentibus Septentrionalibus of 1555.

|

Wind Knots for Sale. Italian Illustration of Olaus Magnus's Historia de Gentibus Septentrionalibus (1555); image courtesy Wikimedia Commons, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Olaus_Magnus_-_On_Wizards_and_Magicians_among_the_Finns.jpg |