Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348

a free multimedia novel by

Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison

|

Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348 a free multimedia novel by Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison |

|

|

|

|  |

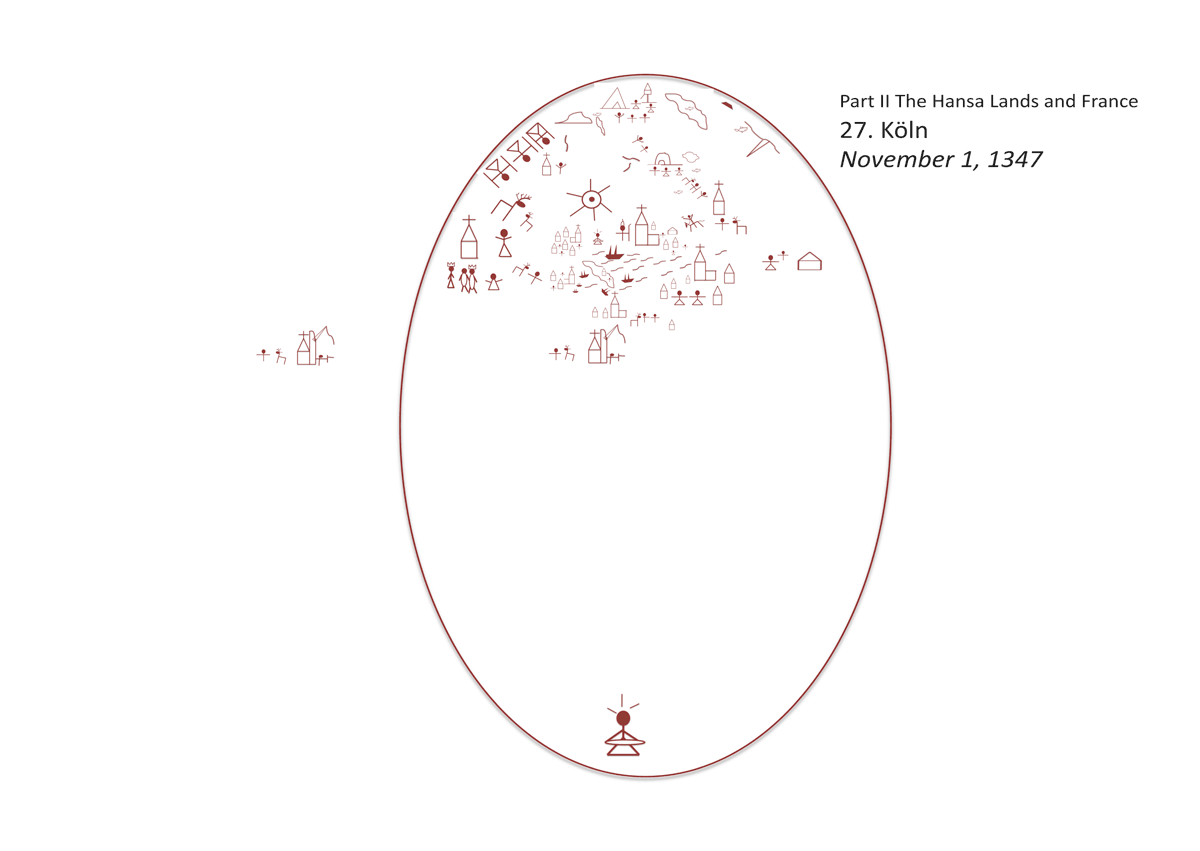

27. Köln [November 1, 1347]

Which of you, wishing to construct a tower, does not first sit down and calculate the cost to see if there is enough for its completion? Otherwise, after laying the foundation and finding himself unable to finish the work the onlookers should laugh at him and say “This one began to build but did not have the resources to finish?”

As they traveled the countryside, Bávlos became more and more comfortable with Simon’s distinctive way of speaking and his many surprising views. Simon liked to argue, and he didn’t mind it when Bávlos held a differing opinion.

“Prove it to me!” he would cry, “Convince me of your point and I may change!”

Bávlos suspected that this did not happen often, but he did appreciate the fact that Simon didn’t expect complete agreement, as Pekka had during their long trek from the north. In hindsight, Bávlos could see that Pekka had assumed Bávlos knew nothing at all—that he was an empty vessel waiting to be filled. Simon, on the other hand, seemed to view Bávlos as a knowledgeable person in his own right, even if his views did not always coincide with the ones Simon held as truth.

“In this world, you learn how nice it would be if others respected your own beliefs,” said Simon, “and then it’s harder to criticize the things that another person holds sacred.”

Bávlos nodded.

“Still,” said Simon briskly, “It is always pleasant to argue, nonetheless! Especially if the person you are arguing with is not going to hang you or burn you at the stake!”

“Do they do such things?” asked Bávlos in shock.

“Believe me, friend Bávlos, they do,” said the old man quietly.

“I am not planning to burn you or hang you,” said Bávlos.

“No, sir,” said Simon smiling, “I know that about you. I almost feel—and you will pardon my chutzpa for saying this—I almost feel that I can trust you.”

“I certainly trust you,” said Bávlos.

“What’s not to trust? A karabeinik, a vantz, a Jew! What harm can I do? And you with letters from a king and queen, no less! And piercing blue eyes…”

They arrived in the city of Köln on a particularly chilly and gray autumn day. Even as they entered the city, Bávlos sensed that his time with Simon had come to an end.

“You go your way, I go mine,” said the old man, with a shrug of the shoulders. “It would not do for either of us to let it be known that we traveled together.”

“I see,” said Bávlos sadly. “I shall miss you though.”

“And I you!” he said. “And even your kalle moid here—I even feel like I may miss her a little!” He gave Nieiddash a gentle pat on the shoulder, and turned away quickly. Bávlos could see that his eyes were filled with tears. Why was it that friendships had to end? thought Bávlos. Why did anything have to end?

“I hate endings,” said Bávlos aloud. “Journeys are much finer when they are still afoot.”

“You speak as a valgerer,” laughed Simon, “a perpetual wanderer. Rattling about like a fart in a barrel. Someday maybe you’ll tire of such travel!”

“Perhaps,” said Bávlos, mimicking his friend’s characteristic shrug of the shoulders, “But I will always appreciate the people I come to meet.”

“I think,” said the merchant cheerfully, “that you will. Indeed, chavver, you are a man of an open heart. Life on you,” he said. With this word, Simon turned and hurried down a side lane. Bávlos watched him retreat.

“I am in a new city and I know no one,” said Bávlos aloud, “No one but you, Nieiddash! What shall we do first?” Nieiddash looked at him with wide eyes and lifted her head upward to smell the wind. All about them the streets were crowded with bustling, chattering men and women. It was like Lübeck or Reval—filled with commerce and life. Bávlos was cheered at once. But he still didn’t know what he should do. Reflecting for a moment, he realized that this was perhaps the first place he had come to on his long journey from home in which he didn’t have a distinct assignment: somewhere to reach, someone to meet, something to deliver. True, he had his goal to reach Paris still before him, and after that to reach Avignon, but what was he to do in this city of Köln? “Show me the way, spirit gang,” he murmured, “for I am utterly without rudder in these waters.”

Suddenly he heard a church bell ring. All around him the people began to hurry up the hill toward a grand and towering church. Bávlos and Nieiddash followed along. As he neared the church itself, Bávlos suddenly stood in awe. It was tall and breathtakingly beautiful, made of sharply cut brown stone stacked to an impossible height and crowned with thrusting spires that looked like thorns on a bush. Beside the church was another area even larger that was still apparently under construction. Bávlos saw the beginnings of a massive tower, crowned by a crane made of sturdy logs. All around were the signs of ongoing and rapid labor: piles of stone, masses of logs, wedges and levers, chisels and saws and planks. Bávlos was amazed at the size of the construction area. He carefully tied up Nieiddash not far from the tower and entered the church.

Inside, the church was packed with people. It was the mass for the common folk and the service had just begun. Bávlos joined with the other faithful, hundreds upon hundreds in number, looking reverently through the rood screen to where the priests and deacons were offering the mass. Later, when a priest emerged with the pax sculpture for the people to kiss, Bávlos gladly filed up toward the altar along with all the other men and women, dutifully kissing the small square of ivory that depicted Iesh on the cross. Everyone approached the pax—young and old, rich and poor, although, Bávlos noted, the richest got to kiss the pax first.

After mass had ended, Bávlos remained to admire the paintings in the church. There was a fine painting of a woman surrounded by many other women standing on a ship.

“Who is that?” Bávlos asked an old woman nearby.

“That?” said the woman surprised, “Why that is none other than St. Ursula! And those around her are her eleven thousand virgins!”

“Eleven thousand!” said Bávlos, his eyes wide.

“Eleven thousand indeed!” said the old woman, nodding smartly, “and every one in heaven today. Every one a martyr!”

“Martyrs?” said Bávlos, “All of them?”

“Yes,” said the old woman. “Killed by the pagan Huns, right here in Köln! Her church is not far from where we stand!”

“When did this happen?” asked Bávlos, trying to sound nonchalant. He felt slightly anxious to hear this news. Perhaps the local populace would hold some strong resentments against pagans, even former pagans, like himself.

“Oh it happened centuries ago!” laughed the old woman. “You don’t have to worry about meeting with Huns around here anymore!”

“Please ma’am,” said Bávlos politely, “Tell me the story of this Ursula.”

“I will!” said the woman. She began.

“Once there lived in the kingdom of England, afar across the sea, a beautiful princess named Ursula. She loved nothing so much as our Lord, and she dreamed of serving him forever as a nun.”

“Ah,” said Bávlos. He thought of the Lady Fina far away in Sweden, and wondered if England was the name they called King Magnus’s realm in this land’s language.

“One day a mighty ruler came to England and insisted that the king give him Ursula in marriage. ‘Give her to me as a wife, or I will take her by force!’ said the wicked king. Ursula’s father was at a loss to know what to do: he was old and weak, and this villainous invader had far greater strength.”

“So he gave Ursula to this man?” asked Bávlos in surprise.

“No,” said the woman. “The father came to his daughter and explained the situation. And Ursula, being a good and dutiful daughter, agreed to marry the man. ‘But first,’ she said, ‘I ask a leave of one year to go and pray with my fellow maidens. And after the days of that year have come to an end, I shall return to be married.’ ‘Let it be so!’ said the king.”

“Now the princess Ursula set to work. She invited any virgins who would like to accompany her to live for a year in prayer, and eleven thousand fine girls, all of noble stock, joined her at once. They sailed away and came to settle here, where the city of Köln stands today.”

“And what happened?” asked Bávlos excitedly. “Well,” said the woman with equal excitement, “the year passed by. And at last it was the day before the end of the year.‘Tomorrow I shall have to marry the king,’ said Ursula, ‘and my life of holy prayer shall be at an end.’ She prayed fervently that day and laid her fate in God’s hands. And do you know what happened on the next day?”

“What?” asked Bávlos, full of wonder.

“A horde of angry pagan Huns stormed the city! They burst through its walls and discovered the holy Ursula and her eleven thousand virgins and they instantly put them all to death! The blood flowed like a river that day, but Ursula’s honor was preserved!”

“Ah,” said Bávlos, somewhat subdued. “And this moment is remembered in the church you spoke of?”

“It has been remembered for many centuries,” said the old woman, “for many centuries. There is a fine church in their honor, and pilgrims come from all over the world to pray for help from the holy St. Ursula and her eleven thousand holy companions! They have a feast of their own, of course, but we also remember them today, on the Feast of All Saints.”

“Ah,” said Bávlos. He thought a moment, and then he asked, “But for whom is this grand church erected?”

“Erected!” laughed the woman, “Hardly erected! Work on this church has just begun! It is a new cathedral built to house an even finer shrine: one that holds the bodies of the Three Kings!”

Bávlos found it strange that three kings would be worth more than eleven thousand and one virgins, at least one of whom was a princess, but he didn’t press the point. Instead he asked, “Oh, did they come here too?”

“They didn’t come here!” laughed the old woman, “Their relics have been brought here from where they used to be in the cursed city of Meiland!”

“Brought here?” asked Bávlos.“Yes,” said the woman. “Our holy Bishop Reinald of Dassel received them from the Emperor Friedrich himself almost two centuries ago, and just about a century ago they began to build this new church to house them! The Emperor took them from the evil Meilanders to punish them for their misdeeds!”

“What were their misdeeds?” asked Bávlos. He wondered what evils one could do to have one’s saints taken away.The woman stared at him for a moment and then said,

“I am only a woman, sir. I do not pretend to understand the squabbles of emperors and Bürghers. The important thing is that the Three Kings are now here, and this cathedral will someday honor them as they deserve!”

“Someday?” said Bávlos. “But this church seems complete as it is!”

“Ha!” laughed the woman. “This is just one side chapel of the church that is planned, sir. One side arm alone. Have you not noticed the grand works outside and the massive tower?”

“I have indeed,” said Bávlos.“The current master builder Gerhard hopes to complete the entire work in just a few years.”

“Ah,” said Bávlos. So that explained all the mess and rubble outside. “Is it possible to do so?”

“He has made a wager,” said the woman ominously, nodding as she spoke.

“A wager,” said Bávlos, “what is that?”

“It is when one person challenges another: ‘I will finish my cleaning before you finish yours!’ If you finish first I will pay you some coins. But if I win, you must pay me!”

“Oh, I see,” said Bávlos. “We have such games where I come from as well.”

“It is a game,” said the woman quietly, “if one treats it as a game. It is something else entirely if the wager grows too big.”

“What do you mean—too big?” asked Bávlos. “How can it harm to challenge someone in a wager?”

“What if they wager something very large,” said the woman. “Something precious.”

“Precious?” said Bávlos.

“Precious,” said the woman, squinting. “Like one’s house. Or one’s spouse. Or one’s soul.”

Bávlos was frightened by the woman’s talk. She seemed to be implying something very strange, but Bávlos could not guess what it might be. “Thank you, kind woman, for sharing your wisdom with me,” he said at last.

“It was my duty,” said the woman with a nod.

As Bávlos walked back toward the grand tower to retrieve Nieiddash, he saw a tall, strong man staring at the construction. He was dressed in a long smock which he had gathered up between his legs to make it easier to stride about. His hose were dark black as were he shoes, which looked sturdy and not as pointy as many typically wore in these parts. He wore a large hat with a wide brim that shaded his eyes from the sun.

“Good day,” said Bávlos, “and happy feast!”

“I wish it were not,” said the man gloomily, scarcely lifting his eyes from the scene he was eyeing.

“Whatever do you mean? “ asked Bávlos with surprise.

“Oh,” chuckled the man, “don’t mind me. I just hate to see the work stop on the cathedral, even for a feastday.”

“You are pleased to work,” said Bávlos.

“I am intent on seeing my work completed!” corrected the man.

Bávlos’ found the man’s tone and ideas curious, and he decided to see if Simon’s delight in argument would be matched by that of a Christian. So he asked with quiet interest, “Is it important that the cathedral be finished?”

“Of course it is!” cried the builder. “What is the point of a building if it is not completed?”

“Well, I thought that it was the building of it that was pleasing to God.”

“Yes, that’s right,” said the builder.

“Well, then, “ said Bávlos cheerfully, “wouldn’t it be displeasing to God if you finished the work?”

“I don’t understand what you mean,” said the man with finality and a touch of irritation in his voice. “How can something incomplete ever be pleasing to God?”

“Well,” said Bávlos, searching for a way to explain himself, “Among my people, we sing songs that have no beginning and no end. They can last only a moment or they can go on for the length of a journey. And while we are singing it is beautiful. But when we have stopped, well, the song is no more. It is gone and we are sad, though the song, I would say, is at last complete.”

“Building is nothing like that,” scoffed the builder. “A building is not a song. The purpose of a building is to create a monument to God, an enduring monument, not a melody hummed while tramping to the market. What sort of monument is a half-finished work? Would you eat a goose that is only half-cooked?”

Bávlos saw the point of the man’s metaphor but he countered with new ones of his own: “A monument that is unfinished is a monument that is still unfolding,” he said, “like a flower opening in spring, or a stream thawing and beginning to flow.”

“It is the completion that makes things complete!” said the builder, pounding his fist against a beam.

“Among my people, completion is always regretted,” said Bávlos.

“Nonsense!”

“Was St. Ursula great during the year that she stayed alive praying, or when she died at the hands of the pagans?”

The builder stared at Bávlos. “You are tempting me in an evil way,” he said. “You would have me go to my grave with that crane still aloft and this work unfinished, and my name would be mocked forever more.”

“You would be leaving something for later people to do,” said Bávlos. “You would be sharing your glory with them.”

“I shall finish my cathedral and none shall stop me!”

“So be it,” said Bávlos, “but I think it is inspiring as it stands.”

“It is a badge of shame on the city of Köln that this cathedral remains unfinished. Already a generation has gone by while God waited for us to complete the work. My father helped built the east transept that you see before you there, but I will complete the rest!”

“What if each generation just did one part,” said Bávlos. “You—”

“You do not understand!” roared the builder. “I will show you! Follow me!” Bávlos had never led anyone into such a fury before. He had seen Simon do so with the old woman in the village of monstrous plants, but in general, the Sámi way was not to provoke argument but to avoid it. Bávlos had learned in life to make excuses when he thought something was a bad idea, or to hide his views in veiled and indirect words. Direct confrontation like this was strange to him, yet strangely exhilarating. He was anxious to see what this Gerhard would do next.

The large man led Bávlos into the cathedral and down to the rood screen. Then he did something Bávlos had never seen a mere man do before: he stepped through the doorway of the screen into the sacred area of the priests. Bávlos stood at the doorway and watched.“Why are you stopping?” said the man impatiently. “Follow me!”

“Into there?” asked Bávlos. “I—I, cannot.”

“Foolishness!” said the man. “I am the maser builder of this cathedral. I give you permission to come into this area.”

“All right,” said Bávlos hesitantly. He felt very uneasy, as if he were stepping too close to a sieidi, or walking in one of the places in the mountains near home that were forbidden to all. No good could come of this, he was certain. The man seemed to feel no such qualms, however. He marched resolutely toward the grand golden box that stood at the back of the altar, not even bowing before any of the sacred objects. The golden box was a tall monument, shaped almost like a cathedral itself, with a long series of elaborate sculptures of gold on its sides and fistfuls of precious gems embedded in its surface. Now that he was this close, Bávlos could see that the sides were rich in blue enamel and red stones. Bávlos gasped at the box’s beauty and size.

“Do you see this reliquary?” said the man, pointing at it impatiently. “It is the eternal resting place of the Three Kings! Do you know who made it?”

“No,” said Bávlos. “I mean, I see it yes, but I do not know who made it.”

“It was made by a very great craftsman,” said the man. “A man named Nicholas from the city of Verdun. He worked very hard on it and he had a great vision.”

“I see,” said Bávlos. He was certain that the kings must have been pleased with his work.

“Come to the other side of the monument,” said the man. “Here. Do you see the sculptures on this side?”

“Yes,” said Bávlos. “They are all very beautiful.” There were sculptures of Iesh, sculptures of his followers, sculptures of his Mother. Some were standing, others were seated, all beneath graceful arches framed by pillars that seemed dwarfed by the figures themselves. The many eyes of the figures stared intently outward at the builder and his guest.

“Beautiful?” cried the man. “Nonsense! This side is inferior! They were done by another artist after Nicholas died. Nicholas did not work swiftly enough and God punished him with death! It took forty-four years to finish this work, and the result of Nicholas’s torpor—his laziness, his foolishness—is that all will ridicule him forever more!”

“I don’t see what you mean,” said Bávlos. “He did what he could and then he left the rest to the next artist. How is that wrong?”

“I see,” said the man chuckling quietly to himself. “You have been sent to tempt me.”

“Tempt you?” said Bávlos. He felt suddenly uncomfortable. The man was eyeing him with burning eyes.“Yes, you are tempting me. You know of my wager.”

“Your wager?” said Bávlos. The conversation seemed to be growing stranger and stranger.

“Yes, the wager,” said the man. “On who will finish our work first, you or I.”

“I don’t know what you mean,” said Bávlos. “I meant no harm. I merely wanted to discuss with you, in the way that Simon the Jew taught me.”

“Aha,” said the man quietly. “Yes, I thought so.” He was now advancing toward Bávlos, who was backing away. “And you know nothing of my wager, with him?”

“Him?” asked Bávlos, backing toward the rood screen. “You have made a wager with Simon?”

“With his master, I think,” said the man, his eyes narrowing to slits.

“His master?” asked Bávlos. “Do you mean God? Have you wagered with God?”

“Quite the contrary,” said the builder steadily, “as you well know.”

“I do not know what you mean,” said Bávlos, “but I know that it is wrong to wager about God’s work!”

“You are judging me?” burst the man in anger. “Am I to be judged by a Teufel?”

“I do not know the meaning of that word,” said Bávlos, “but I think I will leave now.” He had stepped through the opening of the rood screen and was now walking rapidly toward the door. The large man was following him closely, pounding his fist into his palm. By the time Bávlos reached the door he was running. He shot down the hillside to where he had tied Nieiddash and together they began to run away. The angry builder shouted after them furiously:

“I will complete my work, you demon! You will see! Mark my words: this cathedral will be finished within the year!”

“I wish you well,” called Bávlos over his shoulder. “It is a beautiful place.”

“On the whole,” Bávlos decided as he left Köln that evening on his way toward Paris, “on the whole, perhaps it is wise not to enter into arguments with Christians.”