Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348

a free multimedia novel by

Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison

|

Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348 a free multimedia novel by Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison |

|

|

|

|  |

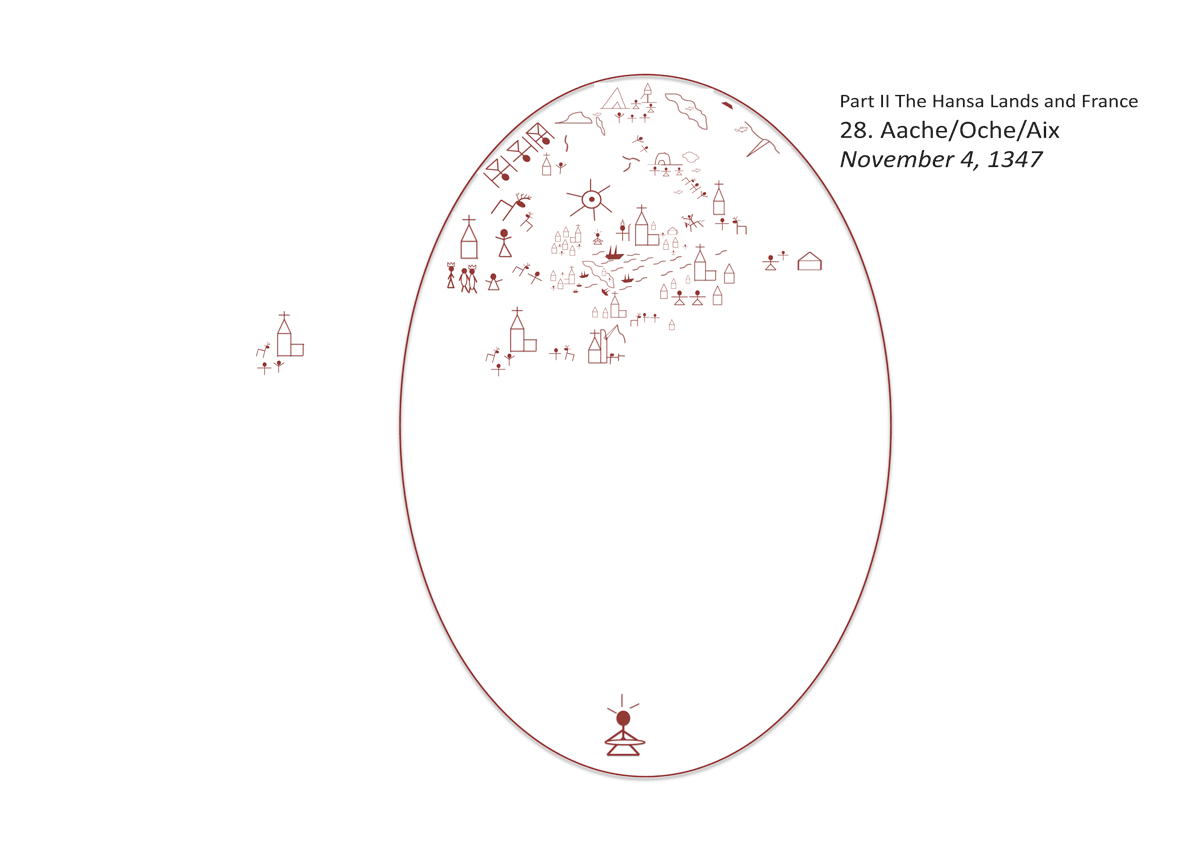

28. Aachen/Oche/Aix-la-Chapelle [November 4, 1347]

Then, girt with a linen apron, he came dancing before the Lord with abandon...with shouts of joy and the sound of the horn.

It was only a few days later that Bávlos arrived at the great cathedral city of Aachen, that locals called Ochen, and that still others from the south called Aix.

Bávlos first came to the Abbey of Burtscheid where a great feast day was being celebrated. It was the Feast of St. Gregor von Kalabrien, the founder of the abbey, and the Cistercian sisters were free with food and drink for all pilgrims. Bávlos attended mass at the great Church of St. Johann, and then strolled out to the square, where there was a fine fountain and lots of people milling about.

Bávlos was drawn to a crowd of people near the fountain and the sound of lively music. From within the throng he could hear a strong voice singing:

Komme, komme Geselle min

ih enbite harte din! ih enbite harte din!

Komme, komme geselle min.

Süzer rosenvarwer munt

Komm unde mache mich gesunt!

Komm unde mache mich gesunt!

süzer rosenvarwer munt.

Come, come my dear,

I long to be you near! I long to be you near!

Come, come my dear.

Your sweet lips of rose,

Come and cure me with those!

Come and cure me with those!

Your sweet lips of rose.

Everyone cheered in delight when the song was finished and Bávlos heard the sound of coins jingling, as if people were throwing coins into a pile in response to the music. He pushed closer to get a better look. There at the center of the crowd he was surprised to see a young boy, perhaps twelve years old, where he had expected a man. The boy was thin and wiry, with long, dark hair and the faint beginnings of a mustache. His chin was pointy, as was his nose, and his dark eyes were set wide apart. He had clearly just gone through a growth spurt and his body seemed gangly and out of proportion as a result. He was a little taller than Bávlos but as thin as a walking stick, with great long feet and long bony hands. He wore a deep green tunic that was generously pleated with flowing sleeves and a belt that was tied high above his waist. His hose were bright red and fitted into shoes that were of soft, dark leather, their toes pointing outward long and straight. He had a hat of black fabric that he wore draped rakishly over the back of his shoulder, held in place by a long scarf. Bávlos walked closer, dug into the bag at his belt and produced one of the coins he had been carrying since Köln. He threw it into the basket the boy had placed before himself, where it mingled with a number of other coins of various sizes and styles.

“Dieu vous donne bon jour, monseigneur le pčlerin,” said the boy bowing deeply with a flourishing wave toward the sky. Bávlos realized that the boy was no longer speaking in the manner of the Hanze traders, although he did not know what language it was.

“Good day,” replied Bávlos in the language of Köln, “Bonjour?”

“Vous estes pčlerin, monseigneur?” said the boy.

“Pčlerin?” Bávlos asked.

“Oďl, pčlerin,” said the boy. He made the sign of the cross and pointed to the road and sky.

“Ah,” said Bávlos “Pčlerin.” He took it that this word must mean one who had been called by Iesh. He nodded eagerly. “Und vous?” he said, mixing words from the Hanze speech and this new idiom.

“Moy, je suis jugleur, monseigneur—chanteur de divers chansons. Je chante en la rue, en taverne, aux bourdeaux…” He nodded and chuckled at this last word, winking as he said it. Bávlos was amazed and dizzied by the boy’s speech. Each word seemed to entail a new movement of the hands and a new tone of voice: his arms moved in and out, as his fingers drew pictures in the air, flitting about like birds, somehow mirroring the acrobatics of his voice.

“Chanteur?” asked Bávlos, picking up on one of the flood of unfamiliar words he had heard.

“Oďl, monseigneur, ung chanteur honneste et moult simple, du nom Jacques le Piquant,” he said, bowing again. He sang some notes to help Bávlos understand. His voice was strong and clear with a pronounced nasal tone that seemed to pervade all of his words.

“Ah,” said Bávlos to himself. “This word means singer. Of course.” He found it strange that this boy seemed to have as a profession what everyone always did without thinking in his land. Did he somehow earn a living by this singing, or was he simply proud of his good voice? There was no way of telling just yet, but Bávlos realized that he had just given the boy one of his own coins himself. Could it be that in this land people paid others to do their singing for them?

The boy continued: “Je sueil chanter et citoler. Et si vous avez une viele, je puis vieler bel et bien.” He pointed at what looked like a small drum that he was carrying, fitted out with strings and a protruding handle. He began to pluck at the thin strings that ran from the end of the handle to the base of the drum, making a delightful sound that made Bávlos think back to the players in Visby on Gotland.

“Citole?” said Bávlos, admiring the instrument.

“Citole,” said the boy, cheerfully. “Et vous, monseigneur, vous estes aussi estrangier ici je devine?” At Bávlos’ look of confusion he added in the Hanze speech “Ook uutländer?—you are a stranger here too?”

“Oďl, uutländer!” said Bávlos—“Estrangier. Je suis estrangier aussi. Je,” he said, making walking motions with his fingers in an attempt to mimic the boy’s prodigious gestures “Paris!”

“Ah,” said the boy in evident delight. “Vous allez ŕ Paris.” Bávlos noticed that the boy pronounced the city’s name differently than they had in Köln or Kalmar: his way sounded like that which Queen Blanche had used so long ago in Vadstena. He had a feeling that this singer was from France, and that he was speaking the same language as the queen had spoken when quipping to herself during their meeting. This must mean that Bávlos was getting closer to France: perhaps he had already reached its borders!

The boy peered at Nieiddash avidly in a way that seemed to indicate his desire to touch her. Bávlos smiled broadly and said:“Nieiddash. Here!” He showed the boy the places on the reindeer’s shoulder where she liked to be petted. The boy stroked her gently and smiled. All at once he announced:

“Monseigneur, oyez-moi, je vous en prie! Par la Vierge pure, oyez mon conseil! J’ay une proposition juste et honorable de vous suggérer.”Bávlos had understood nothing of the boy’s words, but he took it that he was going to be asking something important.

“Oďl?” he said.

“Vostre cerf,” said the boy, pointing at Nieiddash, whom he continued to pet, “C’est une beste droite rage!” Bávlos took this to be some sort of compliment concerning Nieiddash. “Moi,” said the boy, slowing his speech to make himself understood to the stranger, “Je vais avec vous ŕ Paris!” Bávlos was shocked by what he thought he had heard. It seemed like the boy was offering to come with him to Paris! “Moi, je chanterai et citolerai,” said the boy again, “et tout le monde viendra pour voir vostre cerf et ouďr mes chansons! Certes!”

“Ah,” said Bávlos smiling. He seemed to understand what the boy intended. He was suggesting that people would come to see Nieiddash and hear his singing. It was true that ever since Köln, Nieiddash had been attracting a crowd wherever they went. This boy clearly saw that he could earn better money with an oddity along than he might on his own. Bávlos extended his hand and cried “Oďl! Certes!”