Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348

a free multimedia novel by

Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison

|

Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348 a free multimedia novel by Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison |

|

|

|

|  |

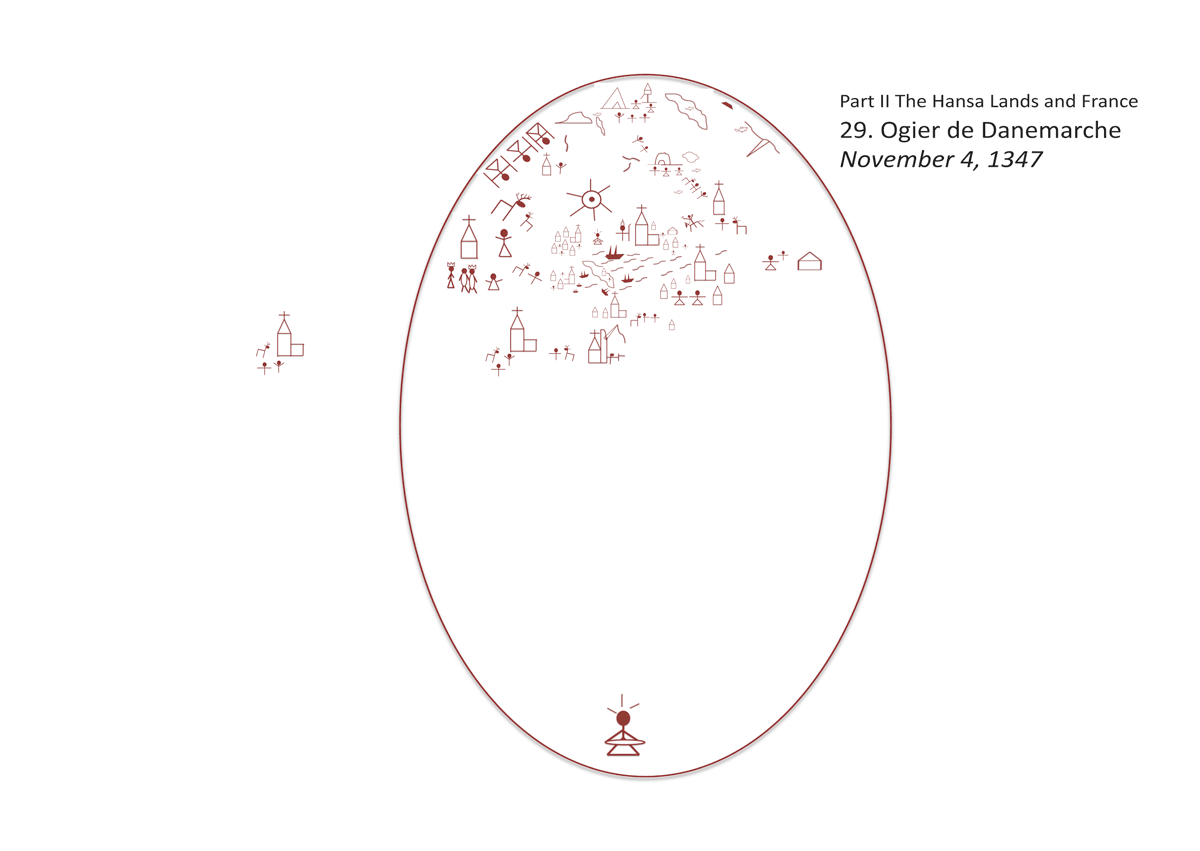

29. Ogier de Danemarche [November 4, 1347]

He grasped the two middle columns on which the temple rested and braced himself against them, one at his right hand, the other at his left.

That evening, Bávlos and the boy talked deep into the night. Bávlos learned that the boy was named Jacques, and that he came from a place called the Barrois mouvant, which had been part of the Duchy of Bar but now, because of some argument between the duke and a king, was no longer so. This Barrois in turn belonged to France, so Jacques was a son of France. He had left his family behind to make his fortune as a jugleur, because that was his greatest talent and ambition. They had pleaded for him to stay, to inherit a fine farm, but he could not get the desire to travel out of his heart, and at last had headed away without even a goodbye. It was a career that he had practiced now for almost a year, and he was apparently famed throughout the region as Jacques le Piquant, Jacques who leaves a sharp taste in the mouth.

Jacques spoke de Hanze speech as well as Bávlos did, although with a different style to his voice, and he also spoke the langue d’oďl, which was apparently spoken in Bar and in Paris, and in many parts thereabouts. Bávlos guessed that it must be the language that folk in the north had referred to as the language of France. Jacques had a habit of saying everything once in the usual Hanze way and then again in this French, as if to clarify what he meant. Bávlos found the habit confusing at first, since Jacques’s Hanze speech sometimes sounded so foreign that he was not always sure which language he was hearing. But soon Bávlos came to notice that Jacques always frowned a little when speaking this foreign language and never moved his hands, while when speaking in the manner of his own people, his voice glided upwards and downwards, darting to and fro along with the most graceful and elaborate gestures.

The words of Jacques’s own language seemed less top-heavy than the ones Bávlos had become used to in his travels since Gotland. The foods they were eating that evening, purchased from a tavern with some of the coins Jacques had earned, were called brood and fleesk and fisk in Hanze speech, but in oďl they bore prettier names: pain, and viande and poisson. Their names seemed to linger in the air longer, and to play through Jacques’s nose as they escaped his mouth. It was as if they were to be savored and enjoyed, not simply spoken. With time, Bávlos found that he was beginning to understand French as well.

“But you,” said Jacques, after a very long story about his career and adventures thus far, and much drinking from a flask of beer they were sharing, “where is it that you come from?”

“From the north,” said Bávlos, somewhat helplessly. He had no idea how to explain the distances he had traveled or the lands he was from. He remembered that Bishop Hemming had called the Duortnoseatnu river “Torne,” but he wasn’t sure that the word would be the same in the Hanze speech, let alone French. And then, even if it were the same, how likely was it that this jugleur from Barrois mouvant would know anything about that river, which, after all, flowed quite far to the west of where Bávlos had actually lived, despite the bishop’s views? So, he simply repeated his statement in oďl, “Je viens du nord.”

“From the north?” said Jacques, delighted, “like Ogier de Danemarche?”

“Who?” said Bávlos. “I am afraid I do not know this man.”

“But that is impossible!” said Jacques. “All the world knows of Ogier de Danemarche, the cherished chevalier of Charlemagne!”

“A chevalier?” asked Bávlos. He was quite puzzled by what Jacques was trying to explain.

“Yes,” said Jacques enthusiastically, “He was a great ridder, a great chevalier!”

“I do not know these words,” said Bávlos. “Ridder? Chevalier?”

“A ridder is what the Hanze folk call a chevalier,” said Jacques, nodding.

“All right,” said Bávlos, “But what is a chevalier then?”

“It is what Ogier was!” laughed Jacques. “How can you not know this, when you are come from the same land as the great Ogier?”

“I think this Ogier came from further south than my land,” said Bávlos, “if I understand rightly what you mean by Danemarche. That is the land that Reval used to belong to before it was given to the Orden, the land that received its flag from heaven when fighting people who were not Christian.”

“Perhaps,” said Jacques uncertainly, “I have never understood much about the lands north of the sea. But I do know what a chevalier is, and that I can certainly explain to you!”

“Do,” said Bávlos. He noticed that Jacques was passing into a new state of mind, as if he were preparing to launch into a great tale of old.

“Well,” began Jacques, “In this very city, in Aix-la-Chapelle, there once lived a mighty and powerful king named Charlemagne.”

“Charlemagne?” asked Bávlos. “Yes, Karl de groot,” said Jacques. “He was the emperor of all these lands and more. He is now a saint, and his body lies in state in the church he built here in Ochen. We can visit it tomorrow!”

“A saint who was a king,” said Bávlos to himself. This was something he had not heard of before. “And this Charlemagne, he lived a long time ago?” he asked.

“Yes, many, many hundreds of years ago,” said Jacques. “Back before these new days. In a time of great chevaliers, a time of chevalerie.”

“Ah,” said Bávlos. He was resigned now to the fact that he was not going to find out what these sorts of words meant right away. Jacques continued his story.

“This Ogier,” Jacques began, “was born to the great King Gaufrey de Danemarche, about whom I am sure you have heard many tales.”

“No,” said Bávlos, “I don’t recall him.”

“Recall him?” said Jacques with a laugh, “why, he lived ages ago! It was he who first destroyed the pagan forces that ruled the north and established the true faith in Danemarche!”

“Ah,” said Bávlos. He didn’t see the point in telling his new friend that the northern pagans had not been entirely destroyed many ages ago, or in fact, that Bávlos himself had been one.

“And on the day of his baptism,” said Jacques, “six beautiful fairy ladies appeared out of thin air to give him their blessing.”

“Fairy ladies?” asked Bávlos. “Do you mean saints?”

“No, not saints,” said Jacques, “Fairy ladies. Pretty, pretty ladies with magic powers.”

“Ah,” said Bávlos. “They were pagans.”

“No, not pagans,” said Jacques, “they were not evil. They were simply magical.”

“Are all pagans evil then?” asked Bávlos.

“Obviously,” said Jacques. “But listen to how the song tells of the fairies! They were wondrous to behold!” He lifted his cithole and began to pluck it gently, making a smooth and even melody that flowed into the night air like the sound of spring water running over rocks:

Six were the ladies who met the babe there,

Six were the ladies, wondrous and fair.

The first caught him up and kissed on his brow,

“Let him be the bravest of all living now.”

The second she took him from her sister’s embrace

“May ever he seek valor in battle and chase!”

“Sister what say you,” said then the third:

“Many the dangers that may stem from your word!

I give to this child a gift not repeated:

Never in battle may he be defeated.”

The fourth sister spoke with eyes that were teasing,

“To all who behold him, may he ever be pleasing!”

The fifth sister spoke: “May you never deceive,

But return in just fashion the love you receive.”

But the sixth sister, who was great Morgan the Fey,

Said to the babe, “Come and see me one day.

And before you arrive there your thirst for to slake,

May never in no wise death ever you take.”

Then they kissed him again at the dawn of that day

And his father had him baptized as prince Ogier.”

“My goodness,” said Bávlos. “This boy was certainly blessed by these ladies.”

“Blessed indeed,” said Jacques, “and their magic held true for the whole of his life!”

“Did he go to see this Morgan?” asked Bávlos.

“He did indeed,” said Jacques, “but that happened much, much later. He had a life of bravery and adventures to experience before then!”

“Did he come here on his way to Morgan’s? Is that how he came to leave Danemarche for Aix?”

“No, no,” said Jacques, shaking his head vigorously. “It was the treachery of his father that did that.”

“His father was treacherous?” said Bávlos.

“Yes,” said Jacques, “he refused to pay tribute to King Charlemagne!”

“Tribute?” asked Bávlos, “What is that?”

“Tribute is the duty and honor which all noble houses and kingdoms and realms must pay to nobles and kingdoms and realms that are finer and stronger than they.”

“Ah,” said Bávlos. He found this notion strange, because back home folk told stories of evil marauders who demanded such tribute of Sámi. And no one ever spoke of these folk as fine. Generally, they were regarded as nasty and deserving to be hoodwinked. “I have a story about such tribute,” said Bávlos.

“Please!” said Jacques, “let me tell you the rest of my tale before we go on to another.”

“Oh yes, of course,” said Bávlos. This would give him time to try to figure out how to tell the story in French. “Please, continue with the story of the boy blessed by pagans.”

“Not pagans, fairies!” scolded Jacques with a touch of exasperation. He launched again into his tale. “This Gauffrey was arrogant. He turned back the good king’s demand of tribute with a cold refusal. And the king replied by sending troops to the land of Danemarche to take the tribute by force!”

“So the king attacked him?” said Bávlos.

“He took his tribute by force,” said Jacques plainly. “And then he took Ogier as ransom so that the king would not fail to pay his tribute again.”

“He took Ogier?” Bávlos was shocked by this turn of events. Ogier had been kidnapped by the great sainted king.

“He took him as hostage,” explained Jacques.

“I do not understand this word,” said Bávlos.

“Hostage means that I take your son so that you will keep your bargain with me. If you do not do so, I torture or kill your son. So a hostage ensures friendship between kings, you see.”

“But,” began Bávlos. Then he shut his mouth. He sensed that it would not be easy to explain why this way of acting would not lead to friendship among his people. One’s children were treasures, and no one wanted their child stolen away by a hostile stranger! He recalled his family’s efforts to hide Elle when Mother had dreamt that she would be taken. In the end, he reflected, it had been he who had been taken, not Elle. Or at least it was he who had chosen to leave. Was he now Iesh’s hostage? Wash Iesh keeping him traveling so that his family would not fail to pay him tribute in the future? He did not think so; He and Iesh were friends. And Iesh seemed much more straightforward than that. “What did he do with this poor Ogier?” he asked at last.

“Poor Ogier?” Poor?” said Jacques, “Monseigneur, you do not understand. For Ogier nothing could have been finer and grander than to come to Aix and become part of Charlemagne’s court! It was the center of the world, full of the flower of every nation. Ogier received a marvelous training here, and he was lovingly cared for by the Duke Namo of Bavičre and prepared to become a great chevalier!”

“But did he not miss his father and mother?” said Bávlos.

“Father and mother!” snorted Jacques, “What are these compared to the glories of the court! Besides, Ogier’s mother soon died, and his father continued to grow ever more dishonorable. He married a horrible woman who wished to make sure that her own son would someday become king. So she counseled the king to pay no more tribute to Charlemagne so that the king would put Ogier to death! Here is how the song tells it:

“Foul was the queen, she thought of her own,

‘I would see my son sit on the throne!

Let Ogier suffer, let Charlemagne break his bone,

And then Denmark’s crown will pass to Guyon!’”

“Could there be such a fiend?” said Bávlos in surprise. He had never imagined a mother being so unkind to a child, regardless of whether it was hers or not.

“Of course she was fiendish!” said Jacques. “She wished the crown for her son. And ambition drives folk to great evil at times.”

Bávlos nodded. None of these things made a great deal of sense to him. But the music was pretty and Jacques told his story well. And anyway, the tale was passing the evening quite pleasantly. “So what happened?” he asked.

“Well, the King Charlemagne grew angry at King Gaufrey. And he treated Ogier poorly to punish that king. But the king did not care; he simply refused to pay the tribute. So King Charlemagne planned to attack the king’s land again and take the tribute by force once again. But then something unexpected happened!”

“Ogier escaped?” asked Bávlos excited.

“No, no!” laughed Jacques. “Don’t you see, he had no reason to want to flee the court of the great Charlemagne. Quite the opposite! In fact, he came to do something that showed his true love and honor for the king.”

“Ah,” said Bávlos, “and what would that be?”

“Well,” said Jacques, singing:

“A herald there came from Rome far away.

‘Alas, mighty king, the pope does you pray:

‘Come help me, my son, for without pity,

the Saracens have come to plunder this city!

Christendom has need of your mighty hand—

Come now to Rome and against them do stand!’”

“The Saracens?” said Bávlos. “Are they Orthodox?”

“No, no!” laughed Jacques. “They are an evil lot who worship false idols that they have brought with them from Arab lands. They are ever the greatest foes of every great Christian king!”

“I see,” said Bávlos. “And how did these Saracens make Ogier do something nice for the king?”

“Wait and I shall tell you!” said Jacques. He sang a long and involved song about many things that Bávlos did not fully understand. It involved Charlemagne summoning his troops, and the colors of banners and horses and equipment that traveled with him to Rome, and the kinds of birds that sang in various trees as the troops left Aix, and the tears of the many women of wealth and nobility who were left behind. It was all very lovely, but it still did not seem to indicate that Ogier would do anything very valuable for the king who had kidnapped him and who was now starving him on account of his father’s bad marriage. At last, Jacques returned to the topic of Ogier:

“Now Ogier came with other young men who had not yet received the honor of going to battle. And he walked with them behind the army and wished with all his heart that he could take up arms against the evil Saracens.”

“Yes?” said Bávlos. He thought that Charlemagne’s strategy had at least had this effect: Ogier was now yearning to kill people who had never done him any wrong, simply because they were enemies of the king who had taken him hostage.

“Well it happened,” said Jacques, “that the dastardly lord Alory had been given the sacred duty of holding aloft the king’s banner Oriflamme! But when he saw the infidels approaching in such great numbers and with such fierce cries and sharp swords, he grew fearful and turned to flee, letting the banner descend!”

“Ah,” said Bávlos. He knew the damage this act could somehow cause when fighting pagans. The priest at Reval had told him all about it. For some reason, pagans tended to gain in power when Christian flags dipped. Ogier, being Danish, must have understood the imminent danger, for after all, was not his country’s own flag created at just such an encounter between pagans and Christians? And had the bishop not had his arms propped up so that the flag would not dip before all the free people of that land were killed or subdued? “What did Ogier do?” he asked.

“Well, he grabbed a club and beat Alory over the head! Then he took his clothes and put them on himself and returned to battle on Alory’s horse, carrying Oriflamme on high!”

Bávlos had to admit to himself that this act was exceedingly brave. Undoubtedly the pagan women’s magic had been powerful indeed. “That was courageous,” he said in Hanze speech.

“It was indeed,” nodded the boy, gazing at the stars. The night had grown silent and the sky shone with stars all seemingly listening to Jacques’s tale of adventure.Bávlos placed another small log on the fire.

“I don’t think I could be so brave,” he said. “Could you?”

“Oh,” said Jacques quietly. “I don’t know. I have never thought of it that way.” He was silent for a while and then seemed suddenly to recall his tale. “But wait!” he said. “Let me tell you what happened next!”

“Do,” said Bávlos. “I am enjoying learning about this man from the north.”

“Well, he carried the banner into the battle and he slew Saracens right and left! And as he was fighting he came near where King Charlemagne was battling a Saracen general named Corsuble.”

“Ah,” said Bávlos. He could guess the rest. Ogier would use the opportunity to kill Charlemagne and then escape back home. “What did he do?” he asked.

“Well,” said Jacques, I will sing you that part!”

“No!” said Bávlos quickly. “I don’t understand your words when you sing them,” he said apologetically. “Your language is still new to me.”

“Of course,” said Jacques patiently. “I will tell you what happened. The mighty Charlemagne had just raised his noble sword Joyeuse to slice off the general’s head, when two other Saracen chevaliers descended upon him, killing his horse and throwing King Charlemagne to the ground! But Ogier rushed to his rescue, and while still keeping the banner held high, was nonetheless able to trample one of the chevaliers under his horse’s hooves and beat the other so hard with his sword that he fell to the earth in a swoon! And so the king was saved!”

“Ah,” said Bávlos quietly. He found the tale exciting but strangely illogical. “What happened then?”

“Well, after the battle,” continued the boy, “King Charlemagne called Lord Alory to him to reward him for his acts of bravery. And Ogier approached in Alory’s clothing and did not reveal his true identity. But one of the other boys could take it no longer and he told the king that it had been Ogier that had saved him. They removed Alory’s helmet and there beheld Ogier’s head. Ogier in Alory’s clothing. Ogier holding the great banner Oriflamme on high! Ogier the hero and savior of the king!”

Bávlos nodded. He was glad that Ogier had received some credit for his work although he thought it strange that Ogier had not spoken up himself. Did he not want the king to know who had helped him? Perhaps deep down he really did dislike this king who had stolen him from his family.

Jacques continued: “And the great Archbishop Turpin, who had spent the day fighting the Saracens with all the bravery and ferocity of a great warrior, laid aside his helmet and his sword soaked in blood, put on his bishop’s hat and staff, and blessed Ogier for his deeds. And the grateful Charlemagne embraced Ogier and made him a chevalier to remain in his court for as long as he should choose!”

“I see,” said Bávlos. “And Ogier was happy about this all?”

“Very happy,” said Jacques. “After all, he was now the favored chevalier of the greatest king on earth.”

“And he came back to stay here in Aix?”

“He did,” said the boy. “There is another tale of his returning to his father’s land, but an angel told him to leave the kingdom to his brother Guyon. So he stayed here instead.”

“And this Charlemagne became a saint?” asked Bávlos.

“Indeed!” said the boy. “We can go to see his shrine tomorrow and then, in the evening, you can tell me your tale.”

“Let us do so,” said Bávlos.