Part II. The Hansa Lands and France

Chapter 29. Ogier [November 4, 1347]

Cultural Explanations

|

Part II. The Hansa Lands and France Chapter 29. Ogier [November 4, 1347] Cultural Explanations |

|

|

In this chapter Bávlos hears about Ogier, a great hero from the north. | ||

| Nieiddash, Bávlos, Jacques, Aix |

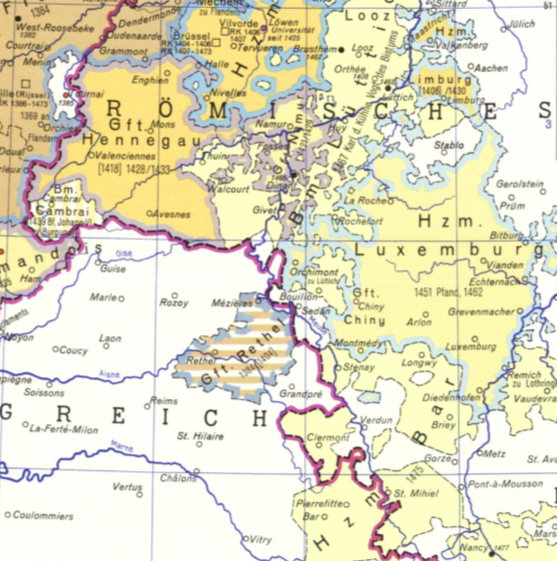

In this chapter, we begin to learn more about Jacques through the things he says about his life and through his storytelling. He mentions being from the Barrois mouvant, a section of the Duchy of Bar, which was located south of the Duchy of Luxembourg, as shown on this map.

|

| Map of fourteenth-century Europe, showing Aachen in the upper right, Luxembourg, and the Duchy of Far. The Barrois mouvant was a section of the duchy that is here shown in white, with Metz as its largest city. These lands now belonged to France. |

Jacques's nostalgia for the chivalry of old stands in contrast with the contemporary realities of his home tract. Barrois mouvant was a portion of the Duchy of Bar which Duke Henry III had been forced to forfeit to King Philippe le Bel of France. Duke Henry had married Eleanor, the daughter of King Edward I of England, and thus sided with his father-in-law in a dispute between England and France over ownership of Gascony. In 1301, after the war had ended, and in punishment for the duke's assistance to England, King Philippe forced him to cede Barrois mouvant ("the moveable Bar") to France, so that Jacques's homeland had the singular distinction of being partly in the realm of France and partly in the realm of the Holy Roman Empire. To Jacques especially, then, perhaps the simple and alluring image of Charlemagne's united Europe proved appealing.

You can read more about this small piece of medieval Europe and its many intrigues HERE.

Jacques recounts a tale of chivalry, the boyhood adventures of Ogier the Dane, the sole Scandinavian in Charlemagne's court.

|

H. P. Pedersen-Dans's sculpture of Holger Danke, aka. Ogier the Dane, displayed in Kronborg Castle, Denmark. Image by Malene Thyssen http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/User:Malene |

People of the fourteenth century did not see themselves as quaint and medieval. To them, their world was fast-paced, modern, and often strikingly hard-hearted, and they sometimes grew nostalgic about the romantic days of old, when knights acted out of honor and kings rewarded faithfulness with companionship and treasure. For people in the region where Bávlos is now traveling, those musings often became linked with the reign of King Charlemagne, and Holy Roman Emperor whose relics were on display at Aix. Jacques, as a jugleur, makes a living celebrating the heroes of that remote past through his songs.

Jacques accompanies himself on the cithole, a medieval lute whose tuning and playing style remains a mystery to us. Barry Ebersole has written a fascinating article on reconstructing a cithole using modern carpentry methods. You can download his article HERE.

The adventure Jacques relates is drawn closely from surviving medieval French accounts of Ogier's childhood, here translated into English in case you can't learn French as quickly as Bávlos.

Charlemagne is described by Jacques as a saint. Here is what the Catholic Encyclopedia has to say about the matter:

He died in his seventy-second year, after forty-seven years of reign, and was buried in the octagonal Byzantine-Romanesque church at Aachen, built by him and decorated with marble columns from Rome and Ravenna. In the year 1000 Otto III opened the imperial tomb and found (it is said) the great emperor as he had been buried, sitting on a marble throne, robed and crowned as in life, the book of the Gospels open on his knees. In some parts of the empire popular affection placed him among the saints. For political purposes and to please Frederick Barbarossa he was canonized (1165) by the antipope Paschal III, but this act was never ratified by insertion of his feast in the Roman Breviary or by the Universal Church; his cultus, however, was permitted at Aachen [Acta SS., 28 Jan., 3d ed., II, 490-93, 303-7, 769; his office is in Canisius, "Antiq. Lect.", III (2)].

To read the entire article on Charlemagne, click HERE. Certainly, in the context of fourteenth-century Aachen, he was regarded unquestionably as a saint, but some of his acts, at least from Bávlos's point of view, don't sound particularly saintly. Nor does the conduct of his archbishop, who moves easily between the sword and the bishop's crozier. But it worthwhile remembering that the stirring tale Jacques relates was told of an era more than five hundred years earlier, when laws and customs were a good deal more rough-and-tumble and when the refined standards of the current day could be imagined to not have existed.