Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348

a free multimedia novel by

Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison

|

Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348 a free multimedia novel by Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison |

|

|

|

|  |

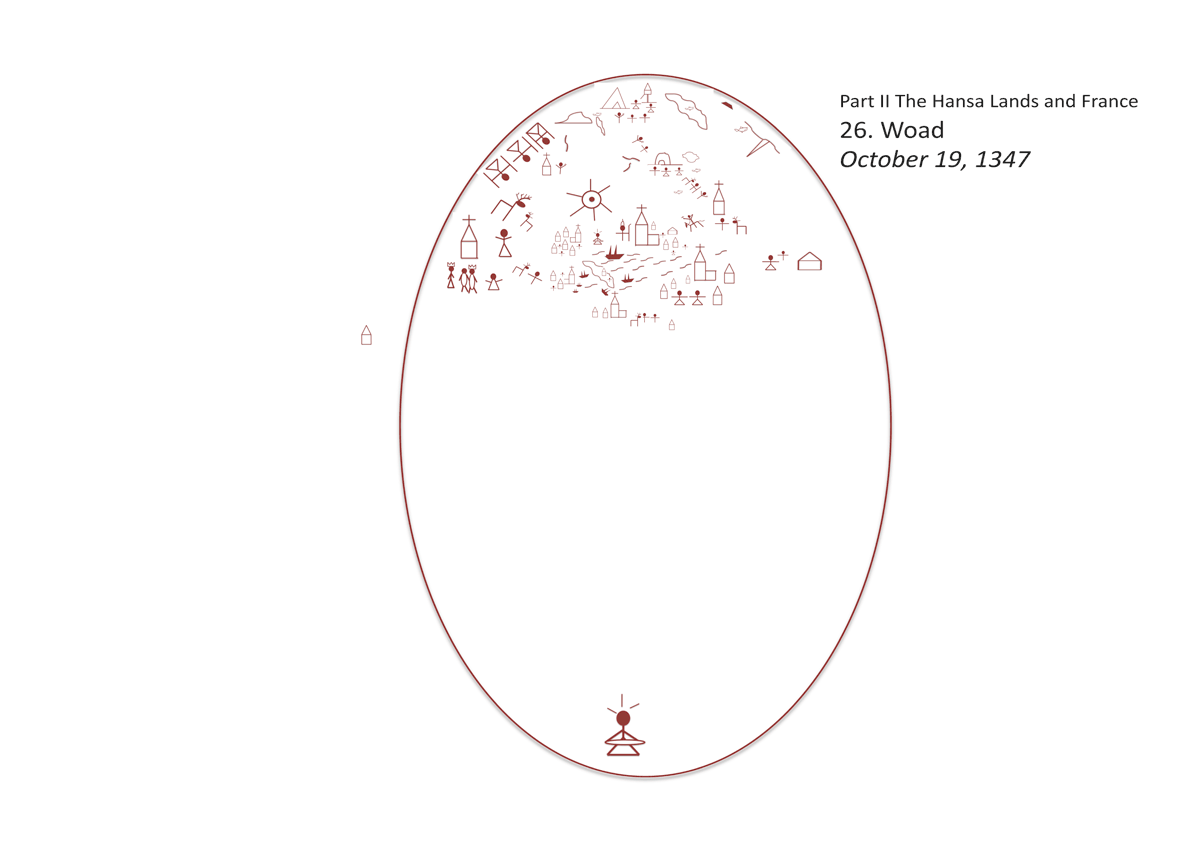

26. Woad [October 28, 1347]

These were thy merchants in all sorts of things,in blue clothes, and embroidered work, and inchests of rich apparel, bound with cords,and made of cedar, among they merchandise….

It was late afternoon as Bávlos and Simon came over the hill into the valley where they hoped to spend the night. They had been walking together for several days and they had become quite good friends. The sun had descended to the horizon on their right and the air had begun to chill. Amid the dried leaves and barren branches of the late-October landscape, there seemed little else alive in the valley. On either side of the lane, the ground sloped away, dark and dry, littered by the blackened remains of plants that looked like they had been burned.

“What has gone on here I wonder?” asked Bávlos looking with perplexity at the land around him.

“Don’t ask me,” said Simon with a snort, “I’m no farmer.” As they walked further, they caught sight of a village, its houses closely clustered and once, no doubt, well kept. Now, however, doors were hanging open and little life seemed anywhere in evidence.

“Why is it that no one lives in these houses?” asked Bávlos. Other villages in the region seemed so brisk and full, yet this one seemed largely abandoned, its fields barren, its dooryards devoid of the livestock and folk that Bávlos had come to expect. It looked as if someone’s luck had been destroyed.

“I don’t know,” said Simon, “but over there is one house that has some smoke coming from the chimney. Let’s go there and ask to spend the night.”At the cottage they found an old woman, a kerchief tied tightly over her silver hair. She eyed the two travellers with great suspicion and gasped at the sight of Nieiddash. But nonetheless, after some coaxing from Simon and the promise of a generous monetary payment for the night’s lodging, she agreed to let the men stay. Bávlos put Nieiddash and Simon’s mule in the otherwise empty cowshed by the house and found a little dried hay to feed them. It did not look like there had been animals here for some time. Bávlos pumped some water for them to drink, but it smelled bitter and unpleasant, and Nieiddash took no interest in drinking it at all. When he had made the animals as comfortable as he could under these circumstances, he walked toward the cottage to join his friend and their hostess.As he entered the cottage, he could tell that Simon had been questioning the old woman on the area’s obvious woes.“The Farwenwäide,” said the old woman, shaking her head,

“The Farwenwäide.”

“The Farwenwäide?” asked Bávlos. He guessed that this must be some sort of animal that had beset the locale, like problem wolves or a menacing bear.

“Yes,” said the old woman, with a grunt and gesture toward the barren fields outside the cottage’s tiny window. Bávlos wondered what she could mean: as far as he could tell, the fields had been largely denuded but for a litter of black seed pockets and the remains of scrappy plants that looked like poor quality cabbage.

“Did you not notice the plants as you came in?”

“Farwenwäide,” said Bávlos. “You mean those fuzzy plants with the black seeds? Are they good to eat?” The woman laughed in a voice at once both bitter and melancholic.

“Farwenwäide is not for eating,” she said. “It is the plant that eats. Eats you out of your home. Eats you out of a life.” Bávlos had never heard of such a strange thing.

“And you plant this Farwenwäide so that it may eat you?” he asked.

“You plant it for use for the Farwen,” said the old woman impatiently.

“Farwen?” asked Bávlos. Here was another word he could not comprehend, although he sensed that it was related to the beginning of Farwenwäide.

“Färben!” said Simon to his friend with a smile and a shake of the head, “making colors for handsome clothes and other things.”

“Ah,” said Bávlos. “So this plant is used to color fabric!”

“Of course it is!” snapped the old woman. “That is why it is called Farwenwäide!”

“I am sorry,” said Bávlos, looking down and hardly moving, “I am not from this country.”

“French?” said the woman, her eyes flashing with ferocity.

“No, no,” said Bávlos. “From up north.”

The old woman mumbled angrily to herself. “One a northerner, the other a Jew. What is a proper woman to do?”

Bávlos tried to regain the woman’s trust with a little more information about his travels. “I am on my way to the Holy Father at Avignon with a message from the king and queen of…of my country.”

“Ah, your country,” said the woman, brightening a little but still retaining a noticeable measure of acid in her voice. “And do you have no rich people in your country?”

“Well, there are,” said Bávlos hesitantly, “but I don’t know them—except for the king and queen, of course.” He decided to leave out mention of Lady Birgitta or her daughter Fina.

The old woman laughed despite herself. “You are an innocent man, I see,”she said. “And I thought you were ridiculing me. I am sorry.”

Bávlos smiled and nodded.

The old woman sighed. “Let us begin again,” she said. “Tell me, friend herald of a foreign king, you who travel the countryside with a Jew, how do you recognize a man or woman of wealth in your land?”

“Well,” said Bávlos thoughtfully, “It is something about their ways. They look as if they expect others to do things for them, and people generally do so. But they do very little in return and always seem disappointed.” He imitated the imperious sneer and sidelong stare that he had come to expect of the wealthy and nobility he had met in his travels. The old woman burst into laughter.

“Indeed you speak true, sir!” she laughed, cutting a biting glance at Simon. “I know the look you mean! So fine, so much better than others. But think now, is there noting about the clothing of the rich that tells you that they are not like the rest?”

“Indeed!” said Bávlos, his eyes brightening, “Now that you mention it, yes—their clothes are different. There are more pieces and layers to their clothing, and they are of many beautiful textures and colors.”

“Such as this?” said the old woman. She had risen and walked to the mantle of her fireplace, where she opened a finely carved box. She pulled out a fine scarf of a rich, blue hue. Bávlos gasped as he looked at the piece. “Farwenwäide,” said the woman, nodding. “The mark of wealth.”

“This scarf is made of Farwenwäide?” said Bávlos, his eyes wide.

“This scarf is made of linen,” said the old woman patiently. “But it is dyed with Farwenwäide. That is what gives it its color.”

“Ah,” said Bávlos.

“Of course, this is just a sample,” said the old woman quickly. “I am not allowed to wear this color myself. Wearing clothes of this hue is limited to fine folk alone. But I was allowed to stain my hands in its juices for five fine years before God’s curse came upon us.” Bávlos could tell that the old woman was preparing to launch into a story, and he leaned forward to signal his interest in the tale.

“It was a spring day when my son announced that we would be planting Farwenwäide. We had never grown such plants in our farm, though we had many sorts of crops and much livestock as well. Farwenwäide was unknown to us as a plant, although of course we knew its color and the wealth it brought to those who dealt in it.”

“It brought wealth?” asked Bávlos.

“Yes of course,” said the old woman, her eyes wide. “It is the most treasured of colors, and all the nobility want to buy it. My son had acquired seeds from a merchant to the south and he had learned the secrets of making the plants yield their blue tint as well.”

“Is it difficult to do so?” asked Bávlos.

“Difficult? Not difficult to grow, no,” said the old woman, “Once you’ve got a supply of the seeds. Each year you can plant more and each year you can harvest more leaves. The leaves are difficult to make into color however. You have to soak them in urine.”

“In urine?” said Bávlos with surprise.

“In urine!” said the old woman, smiling. “Yes the color of the nobility comes through piss. I should have known from that fact that it was a bad idea to plant these seeds.”

“Bad idea?” asked Simon, breaking in. “But did you not earn a handsome price for the plants you grew?”

“We did, we did indeed, “ said the old woman, slowly shaking her head. A fine price, a tempting price. And each year, my son planted more and more of our land with seeds from the plant, and each year, we had less and less to eat besides.”

“How could you live then?” asked Bávlos.

“Silly,” said the old woman, looking at Bávlos, “we had money from the plants. We could get what we wanted to eat through trading coins for it, and there seemed no end to these coins. The Farwenwäide, it was like a money plant.”

“But what happened then?” asked Bávlos. Clearly something momentous had occurred.

“Well may you ask,” said the woman. “We provoked the Lord with our greed.”

“You did?” asked Bávlos. He had not realized that Iesh would punish in this way.

“Yes,” said the woman. “After the first years, we began to notice that nothing else would grow in our fields but the Farwenwäide. It was as if all the other living things had forsaken us and our lands. And the more we planted the one thing that still grew, the less it flourished. Soon we had tiny crops of Farwenwäide that yielded less in coin than we could live on through the year. But no other plants would grow anymore. We planted beets—spindly bits of Farwenwäide came up. We planted cabbage—Farwenwäide came up. We tried to seed grass and grow hay for our hungry cattle—Farwenwäide came up. And then the water turned bitter and the smell of urine infected our nostrils so that our very food tasted like refuse from a latrine.”

“Ah,” said Bávlos quietly, “How unpleasant.”

“Unpleasant?” spluttered the woman, “Unpleasant you call it? It was disastrous. No one could live. One by one the families of the village began to move away. They moved in with relatives in other villages and they left their homes abandoned. My son left home with his family and only I chose to remain behind. I am too old to move, and before long I shall die. The villagers come back to check on me every now and then and I manage to eek a living from the little land that still yields food. But the water is still bad and before long it will be impossible to stay.”

“This is very sad,” said Bávlos.

“It is the Jews’ fault!” said the woman, glowering at Simon.

“How is it the Jews’ fault?” said Simon angrily.

“You’re the merchants!” said the woman, “You told my son to grow this weed!”

“It was a Jew who told him such?” asked Simon, narrowing his eyes.

“Well, no,” said the woman, hesitating, “It was a Christian merchant from the city of Jülich. But—”

“But what?” said Simon quickly. “You were given the seeds and the encouragement to plant them by a Christian. You did so and harvested this plant according to a Christian’s instructions. Then you processed the leaves in the way that he told you in order to make the dye, yes?”

“Well, that’s correct,” said the woman hesitantly.

“And yet, you blame the Jews for your misfortune!” said Simon with a sweeping gesture.

“Yes,” said the woman, straightening up and seeming to gain new vigor, “Yes I do. It was the Jews’ example that led to this folly. The Jews’ greed infected us all!”

“It made you Jewish?” asked Simon, in mock seriousness.

“Of course not!” snapped the woman, crossing herself. “But it made us act like Jews!”

“Ah,” said Simon quietly, looking down at his hands. He seemed to realize that there was little point in trying to reason with this woman and her prejudices.

“The main thing is that my lands are ruined and someone is to blame!” said the woman vehemently.

“You are looking for a scapegoat,” said Simon. “You may decide to blame the Jews. Go ahead. But you know in your heart that God’s rod has come down upon you for what you did yourself, not for something my people did to you.”

At that, the old woman rose from her seat with a look of utter fury. She grabbed a heavy pot and began to advance upon Simon. Bávlos sprang to his feet and pulled Simon off his chair. They backed away quickly toward the door.

“Good mistress Farmwife,” said Bávlos quickly. “Please forgive our many questions. We will leave you now with our thanks for your hospitality.”

“Get out!” sputtered the woman through clenched teeth. “Leave my farm at once!”

“Until we meet again!” said Simon, trying to regain a civil tone.

“Out!” repeated the woman, pointing at the door. “You cloth merchant, you tempter, you deceiver!”

The friends hurried to the stable and retrieved Nieiddash and the mule and then retreated hastily to the road. They walked a long while before either of them spoke.

“Hmph,” said Simon. “A fine balebuste! The old machshaifeh!”

“I do not understand your words,” said Bávlos.

“I could have warned her it might happen thus.”

“How so?” asked Bávlos.

“Did you not hear her?” asked Simon. “For five years they planted this Färberwaid; five years.”

“Yes?” said Bávlos. He wondered if there was something potent about that particular number that had caused the problem.

“Five years of planting the same crop, never giving the land a rest!” said Simon. “They have not read or understood the Bible. It says clearly in the Torah that farmers should cease to plant every so often, to give their fields a Sabbath, a time of rest. Why then did they continue to plant for even a sixth year?”

“This resting would have helped the land?” asked Bávlos.

“Of course!” cried Simon. “Look at your beast, your Nieiddash. Can she travel all day every day with never a time to rest?”

“No, of course not,” said Bávlos.

“And yet,” said Simon shaking his finger as he spoke, “they work their land without pause and grow furious when it falls dead in exhaustion!”

“And God has punished them for this act?” asked Bávlos.

“He has punished them for their greed, yes,” said Simon with finality. “The sins of the father will be visited upon the children, so says the Lord. ‘I the Lord, your God am a jealous God, visiting the iniquity of the fathers on the children, and on the third and fourth generations of those who hate me.’ It will be many years before this land is bountiful again.”

This sounded very unreasonable to Bávlos. “In my land,” he said, “the gods we know never hold grudges so long. When they get angry they take revenge at once. And when you appease them, they forgive at once as well.”

“The God of all creation, is not so fickle!” said Simon. “Believe you me, he will strike these Christians for their misdeeds—the day is coming when they will see his wrath!”

The two men walked on in uncomfortable silence. It was midnight before they crossed into the next valley and left the bitter lands of the village behind. They found a place to sleep in a glade by a stream, where Nieiddash and the mule drank at last of the clear and running water.