Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348

a free multimedia novel by

Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison

|

Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348 a free multimedia novel by Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison |

|

|

|

|  |

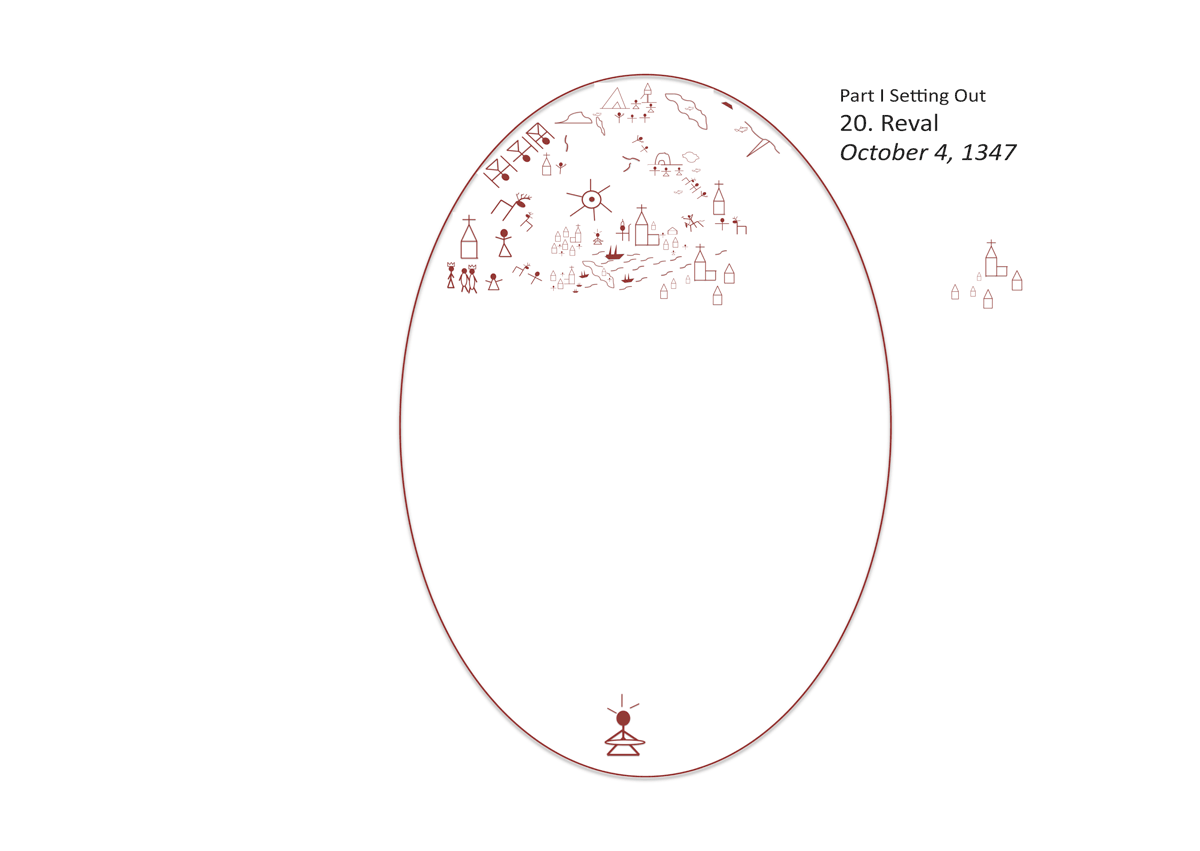

20. Reval [October 4, 1347]

Behold, I am sending you like lambs among wolves. Carry no money bag, no sack, no sandals; And greet no one along the way…. Stay in the same house and eat and drink that is offered to you, For the laborer deserves his payment.

It was morning as the city of Reval came in sight, its tall spires silhouetted against the gray autumn sky. The waves of the sea were gray-green and strong, as if a storm had recently passed and its memories lingered in the surf. All at once Bávlos realized how difficult it might be to find the church that had purchased Master Claes’s statue, or the worthy Sir Stig Andersen who had promised payment. From the sea, the city looked like a mass of church steeples, each crowding the other, all craning upwards towards heaven. Bávlos could see steeples both in the lower city and high above on the bluff upon which the city’s finest buildings stood.

“I will have to trust in you, oh Virgin, to help me find the way,” he said with resignation.

By midmorning, Ulf and his sons had managed to tack into the port and Bávlos was able to disembark. He gratefully took leave of the captain and Per and Gunfjaun and said that he hoped they’d meet again on Gotland. Then he carefully loaded the statue on his back and headed toward the city gate. The statue was snugly wrapped in its soft blankets, but Bávlos could still feel the arms and heads of its Virgin and child on his back. It made him happy to think that he was carrying such a cargo. He saw many people all about him, carrying loads of goods on their backs and headed in the same direction. A small woman walked beside him, gazing intently at his clothes and smiling up at him. She had a wide, happy face that somehow reminded Bávlos of his mother’s. He smiled back at her and nodded. Her skin was very pink and her nose was blunt and bent, like the ones he had seen in Ĺbo. Her clothes were made of rough linen, with an apron of dark brown, embroidered in with threads of red, yellow, and orange. She wore shoes of woven birchbark, much like those Bávlos recalled from Finland. She seemed content to walk beside him, staring as he went. Before long they came to a wide stone gateway, with a cross mounted above it and guards stationed below. Bávlos took a deep breath and strode up to one of the guards.

“I am looking for Sir Stig Andersen,” he said in his best Swedish.The man laughed. “Stig Andersen? Stig Andersen? Joh, he is all wegg!”

“Wegg?” asked Bávlos. This man’s speech was nothing like that of the Swedes,’ even if words seemed strangely similar. He spoke the language of the traders that Bávlos had first heard in Turku and again in Stockholm and in Kalmar. He wondered now what the man had meant. Could this wegg mean “away”?

“Ja kiek!” said the man again, “All wegg. Joh, all eens Jaor wegg.” He pronounced Jaor with great emphasis and Bávlos instantly guessed that it must be the local variant of what the Swedes called ĺr, a year. As his momentary elation at understanding the guard faded, Bávlos began to realize the gravity of what he had just been told. It was discouraging news indeed. The man that had hired Master Claes so long ago seemed to have gone.

“When will he come back?” Bávlos asked in Swedish. He felt a sense of panic rising. The guard seemed not to understand. Bávlos tried to pare down his question to the essentials: “Stig Andersen kommer…” he said, “Stig Andersen comes—”

“He kömp zwar niemaols,” said the guard with finality. “He is in Dänemark wieder.”

“Danmark?” asked Bávlos surprised. Was this not Denmark that he had arrived in—a part of Denmark far to the east? Why had Stig Andersen gone? And why did this man speak of Denmark as if were a foreign place?

“I have a sculpture,” said Bávlos, a note of helplessness in his voice. “A sculpture for Stig Andersen. A sculpture for the church here in Reval.”

“Welke Karke?” asked the guard. He seemed to have understood at least some of what Bávlos had said.

Bávlos thought for a moment. He noticed that the woman who had been walking beside him on the way to the gate was still standing alongside, watching with a bemused smile. “Den Helige Själs…” he started.

The guard finished his sentence for him: “Joh, Heeliges Geestes Karke.”

“Yes,” said Bávlos with a smile of relief. The name sounded nothing like it did in Swedish. The guard nodded and briskly began to give him directions for how to reach the church. Bávlos could make out that the path involved walking, going down a street, turning somehow once, more than once, in some direction, and then the church would be plainly in sight. The guard had finished his directions now and was smiling broadly. Bávlos smiled and nodded gratefully, and started through the gate. The woman continued to follow, chuckling quietly and shaking her head. Bávlos felt confused and embarrassed. He spoke quietly to the statue on his back in Sámi, “Help me find the way, Mother.”

“I will!” came a voice within his head. Bávlos knew not to look around this time: it was undoubtedly the Virgin’s voice, reassuring him that she would guide him in this task.

As he walked through the city, Bávlos noticed that it looked much like Visby only much more crowded. The buildings were packed more closely together, and seldom was there any break between where one house ended and another began. They were taller, too: great towering houses with beams sticking out of upper stories. The beams were used as the anchors for pulleys and Bávlos could see many people busily pulling loads of goods up into upper storerooms by means of the pulleys and ropes. They had doors open high in the garrets of their houses and men aloft were calling down to others below, who were loading goods into baskets or onto platforms to be hoisted up. They all seemed incredibly loud and cheerful and they all seemed to be speaking the same language as the guard had used. Master Claes had told Bávlos nothing about what to expect in this place, and Bávlos had not realized it would be so different from the towns he had come to expect in Sweden. He looked over his shoulder and saw that the same woman was following along behind him. She smiled at him again. He smiled back and nodded. “Heiliges Geistes Kirche,” he said.

“Yes,” she said. She motioned with her nose that it lay ahead. Bávlos walked onward. After some time, he came to a kind of courtyard in the narrow city streets where he saw a great tall stairway and a magnificent doorway. Its doors were beautifully carved and men in fine dress seemed to be hurrying in and out of them continually. He wondered if this were the church. Suddenly he felt a gentle tug at his sleeve and he turned to see the woman again, smiling up at him. She pointed to a lower door on the other side of the street: Bávlos could tell at once that it was the church. He smiled gratefully at the woman and crossed to the other side. The woman followed.

As Bávlos entered the church, he found it dark and peaceful. It seemed to have two aisles, with pillars down its very middle. There were many beautiful chapels along the sides. Bávlos walked slowly down the first aisle, conscious of the huge bundle he was still carrying on his back. At last he noticed a priest, a tall, powerful man with a red bulbous nose and hands the size of baskets dressed in a simple cassock of grey linen, a large hood trailing down his back. He was the largest and huskiest priest Bávlos had ever seen.

“Holy Father,” said Bávlos in Swedish, “I have a sculpture for the church.” The man seemed at first not to understand, but eventually he noticed the large bundle on Bávlos’s back and ushered him out of the church to a room to the side of the main altar. There Bávlos was able to set the bundle down carefully and retrieve the letter from underneath his tunic. The man motioned for Bávlos to have a seat and sat down as well. He carefully opened the letter and began to read. It seemed very difficult for the man, as he squinted down at the letter, trying to make out its words and turning the page in different directions in what seemed like utter confusion.

While the man read, Bávlos looked around him intently. He felt a deep sense of relief in this place, as if Iesh had led him to the place he needed to be. He looked down at his hands and waited for the priest to speak. At length, the priest cleared his throat and began to speak again in the language of the guard, but very slowly and with much more clarity. Again he seemed to indicate that Stig Andersen was no longer there, that he had returned to Denmark, the land of his king. This land, the priest went on, The Herzogtum von Estland, no longer belonged to Denmark: the king had given it to the Orden and it was now part of the Ordenstaat.

By carefully listening to the priest’s words, Bávlos began to be able to construct questions of his own in the local language. “The Orden—what is that?” he asked. The man nodded happily and began to explain. Bávlos did not understand much of what the priest said but what little he did comprehend seemed very strange indeed. Apparently the Orden was a sort of society or army of monk-soldiers. They were called by Iesh to come to the Ordenstaat and fight against the heathens of the land as well as the evil Russian heathens to the east. They came from all over the world, often as penance for great sins they had committed, and they lived in castles throughout the land of Livonia and now also in Estland. King Valdemar of Denmark had given the Orden the Herzogtum of Estland as a present when his own brother, Sir Otto, had joined the army of monks in the city of Marienborg.

“And King Valdemar gave you this land as a present?”

“As an offering,” said the priest, nodding gravely. “He asked us to pray for him daily and we do so in all the churches of the Ordenstaat.”

“And you convert the heathens?” asked Bávlos.

“We try to,” said the priest, his face darkening. “It is difficult.”

“Difficult?” asked Bávlos.

“Their hearts are with the Devil,” said the priest gravely, leaning forward as he spoke.

“Ah,” said Bávlos.

“Yes,” continued the priest. “No one has had much success with the heathens of this land. Their hearts are of stone. Of stone! When King Valdemar first came to this land a century ago—King Valdemar Sejr, not the present king Valdemar of Denmark, but his glorious ancestor—God granted him victory over the heathens in a fine battle. He and his men sailed into the bay of Lyndanisse. And God sent an angel to drop a flag, a beautiful flag: a field of blood red with a cross of white upon it. The Dannebrog. The flag of Denmark ever since. And this flag was taken up by the holy bishop Anders Sunesen, and as long as he held it aloft on the hill above the battle, the Christians prevailed against the evil pagan force. But as the battle waged, the holy bishop’s arms grew tired and the flag began to dip. And as it dipped, so dipped the fortunes of the Christians, and the monstrous, evil, warlike horde of pagans began to take the day. The king saw what was happening, and he propped up the bishop’s hands so that he could hold the flag aloft without tiring. And do you know? The Christians were able to win the day! They slew masses of pagans and built the castle that is upon the hill of this city ever since. So has God ordained that this land will be Christian, even if its backward and blackhearted people must be stamped out to make it so!”

Bávlos smiled and nodded uncomfortably. This priest was nothing like any priest he had ever met before. Not even Bishop Hemming had seemed so full of wrath toward his enemies, the heathen Orthodox of Novgorod. Was this priest and his order truly answering the call of Iesh? Did Iesh call some to this kind of life? And did Iesh punish a refusal to convert in such violent and merciless a manner? What would Iesh do to Bávlos’s family back home? Would he stamp them out too? These were difficult questions to answer, and Bávlos sensed that it would not be prudent to raise them in the present company. So he turned the conversation, as best he could, back to the question of the sculpture. Carefully he unveiled the statue, which the priest seemed to like immediately. As the priest admired the workmanship, Bávlos tried his best to explain.

“Stig Andersen asked Master Claes of Gotland for this sculpture. A fine sculpture! Master Claes, long he worked—“ Bávlos mimicked the craftsman’s careful work with chisel and hammer, the carving, the smoothing, the coating with cheese and chalk, the painting, the varnishing. “His hands,” he continued, wringing his own hands with a grimace of pain. “Master Claes is, is, not young,” he said. The priest seemed to understand everything, for he nodded and listened carefully as Bávlos spoke.

“Let us see this sculpture,” said the priest. Carefully, Bávlos removed the statue from the layers of woolen blankets in which it had been wrapped. As it came into view, the priest gasped in wonder.

“Ein Liebchen,” said the priest, bending over and gazing at the figure of Iesh. “Mit dem Liebfraumilch.” He seemed transported by the image of the little Iesh about to partake of his mother’s breast. Tears welled in his eyes, and Bávlos watched as he quickly dabbed them aside and stood up to address his guest.

“Stig Andersen said this much for the sculpture, said Bávlos, taking up the letter that the priest had not seemed to understand. He found the place where Master Claes had written the number of coins he was to receive, the many surprised men in a line with the series of fence posts. The priest seemed to understand the number and nodded again. “Master Claes,” said Bávlos plaintively, “He needs this money!”

The priest nodded and looked at the ceiling. He seemed to be thinking hard before talking. At last he said: “Stig Andersen is gone. This is now the Ordenstaat, not Denmark. But this church is still a church, and this statue belongs here. ‘The laborer deserves his payment.’” He said the last sentence with great finality, as if it explained all that needed to be said. He rose to his feet and walked to the corner of the room, where he took out a small treasure chest. He began to count out coins to hand over to Bávlos. Bávlos was filled with relief and joy. “The laborer deserves his payment,” said the priest again, when at last he handed a sack of coins to his guest.

“Thank you, kind Father,” said Bávlos.

“It is nothing,” said the priest smiling. “In God’s plan, we each receive what we deserve.”