Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348

a free multimedia novel by

Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison

|

Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348 a free multimedia novel by Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison |

|

|

|

|  |

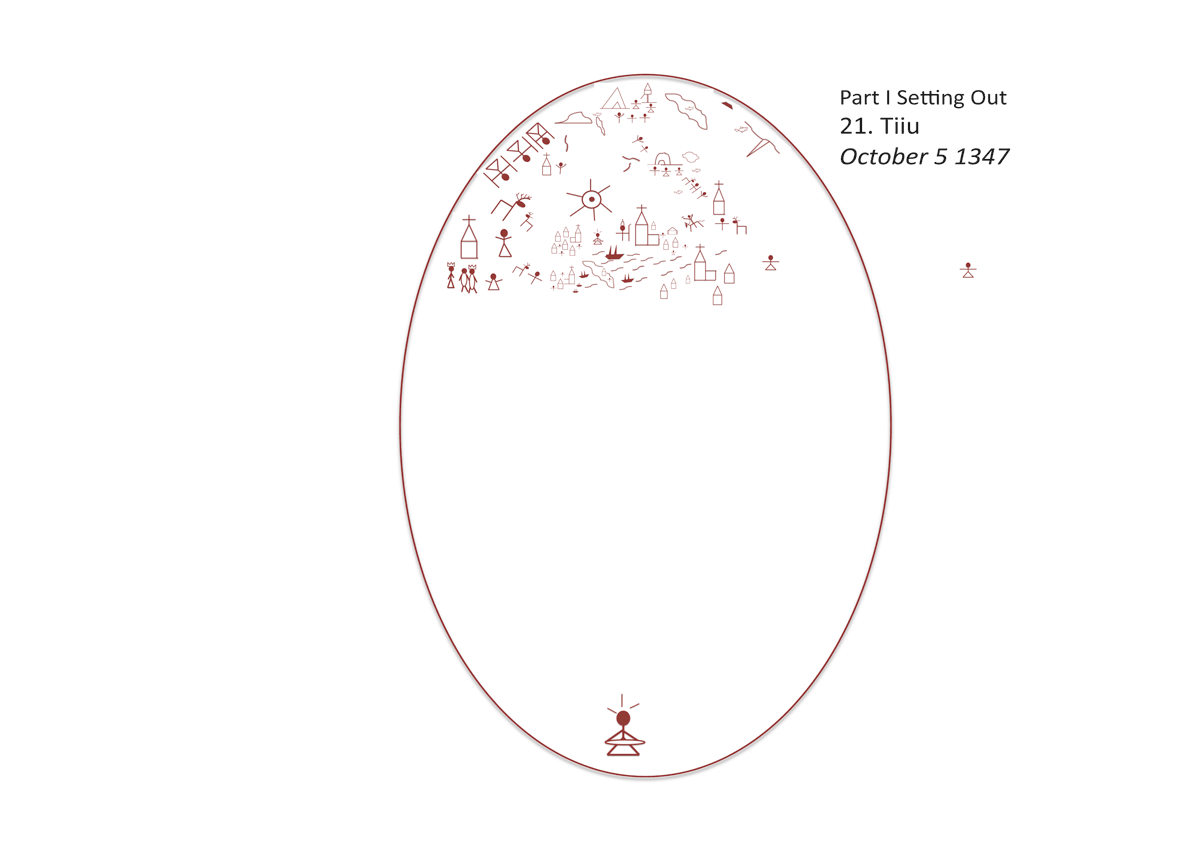

21. Tiiu [October 5, 1347]

They marveled at her beauty, …and they said to one another, “Who can despise this people that has such women among then? It is not wise to leave one man of them alive, for if any were to be spared they could beguile the whole world

As Bávlos re-entered the dark church, he felt a great joy. Not only had he managed to find the church for which Master Claes had made the statue, but he had been able to collect its payment as well. Now he could leave this large and strange priest behind him and return to Gotland to collect his reindeer and be on his way toward Avignon. As he walked briskly through the church, he noticed that the woman who had accompanied him on his way to the church was still there. She smiled when she saw him. He nodded at her in thanks for her help and stepped out of the church into the daylight. The woman followed behind. Bávlos was beginning to find her presence disconcerting, so he turned at last and addressed her.

“Good day,” he said in German.

“Ah,” she said. “Sina oled keeletarkk.” It was strange to hear this woman’s talk. It was not German at all, but like a mixture of Finnish and Sámi, strangely familiar.

“Keeletarkk,” said Bávlos. “Gielládárki. Yes I am that.” She knew about his power.

“Ah,” said she. “We have heard of your kind.”

“You have?” said Bávlos in surprise. He had no problem understanding her, as she seemed to be speaking simply a strange form of the same language that Bávlos had learned from Brother Pekka so long ago.

“Yes, we have tales of Lapp travelers with the ability to speak and understand all languages. You come to us as from an ancient tale.”

“I am just a simple traveler,” said Bávlos, suddenly tongue-tied, “come to deliver a carving and then to continue on my way.” He had never heard of Sámi travelers to these parts, nor could he understand why this woman seemed so familiar to him, like an old friend from many years ago, or a distant cousin that one had not seen for a long, long time. “These others,” he said, “where did they go?”

“Ah, here and there, far and wide,” said the woman shaking her head. “Sometimes on great travels. Sometimes to the very doorway of the Underworld.”

“They went alone?” asked Bávlos.

“Sometimes,” said the woman. “But more often they went along with heroes of our people: great leaders of the days before the lords and barons came from beyond the seas. The monsters who have stolen our lands from us.”

“Ah,” said Bávlos, “the Christians.”

“They call themselves such,” said the woman.

“How is it that your language—” started Bávlos.

“How is it so like Finnish?” she asked.

“Yes,” said Bávlos. “It is practically the same.”

“We are the people of this land,” said the woman simply. “We belong here just as the Finns belong on the other side of the water. And we call all things by their proper names.”

“And the Orden,” said Bávlos.

“The Orden, the Danes, the Swedes, the Russians. They come from elsewhere. They bring us sorrow. They steal our land.”

“The priest says that they want to convert you.”

“Ha!” laughed the woman. “Convert us into corpses. Christian corpses with no complaints.”

Bávlos nodded silently. He could understand this woman’s viewpoint well. If Iesh had called him in the way these Estonians had been called—through an attack from a foreign army, with a bloody flag fluttering down from the sky—would he have listened so readily to Iesh’s words? If he had seen his family and neighboring communities destroyed by monk priests, who hid in castles of stone and iron, would have welcomed their teaching in the way that Bávlos had welcomed that of Pekka?

“You are tired,” said the woman. “You have traveled far. Come and eat at my home. My husband will be thrilled to mean a keeletarkk Lapp.”

Bávlos and the woman now walked easily along. She told him that her name was Tiiu, and that her husband was named Ülo. They lived outside the city in an Estonian village. Bávlos introduced himself as well and described his homeland near Sállivárri. The woman seemed very interested. “You have reindeer?” she asked.

“Yes,” said Bávlos. “I even have one with me. But I left her in Gotland while I delivered this statue to the church.”

“Did you make that statue for them?”

“I helped an old man named Master Claes to make it.” said Bávlos. “He had been asked to make it by someone called Stig Andersen.”

“Stig Andersen,” said the woman, nodding. “The king’s henchman.”

“Ah,” said Bávlos.

“We rose up against him four years ago, on the feast of their warrior saint, St George. We were tired of the Danish tyrants and their ways.”

“What happened?” asked Bávlos, excited by her tale.

“Stig Andersen holed up in his castle there in Taannilinn.”

“Taannilinn?” asked Bávlos. “Reval,” said the woman, “The fortress of the Danes.” “Ah,” said Bávlos.

“He was trapped like a rat,” she said with a smile.

“And then?” asked Bávlos.

“And then,” sighed the woman, “The Orden stormed in. They had been waiting for an excuse to invade all along. Now they could come and ‘restore order.’ They did so, killing scores of our people, setting homes on fire, raping women, raiding our livestock, and hiding in the castles of the Danes. “

“The priest at Heiliges Geistes Kirche—” said Bávlos. “Püha vaimu,” said Tiiu. “The name of the church is Püha vaimu.”

“Ah,” said Bávlos. “Anyway, the priest there said that the king of Denmark had given Estland to the Orden as a gift.”

“As a gift!” laughed the woman. “As a gift. It was not his to give. It was ours. It is not ‘Estland’—it is maa—our land.”

“But he gave it to them so that they would pray for him?” asked Bávlos.

“He gave it to them for a price,” smiled the woman. “A gift that earned the king nineteen thousand marks of Köln.”

“Köln?” asked Bávlos.

“A great trading city of the Germans,” said Tiiu. “Their coins are used everywhere.”

“Ah,” said Bávlos. “So the king sold them this land.”

“He sold them our homes,” said the woman. “He sold them our meadows, our forests, our waters, our fields, our livestock. He sold them our mines, of silver and gold, and even of salt. He sold them our wildlife, and the fish of our waters. He sold them our women and men, our children, our sons and daughters. He took his money, placed his sniveling brother in the order and left us to our fate. And now life is even worse.”

“And these Germans treat you badly?” asked Bávlos.

The woman laughed. “They do,” she said. “They will pay for their deeds in the next life, though.”

“The next life?” asked Bávlos.

“Yes,” said the woman. “I will sing you a song of the next life if you’d like.”

“Yes, please!” said Bávlos eagerly. No one had offered to sing him a song since he had left his father’s lands. The woman smiled and cocked her head. She sang in a loud strident voice a song that sounded like a joik, but unfolded with a slow repeating rhythm, and a pleasantly melancholic tune.

“Where did the slave sleep at night,

Where did the servant slumber?

Out in a sweeping swamp Inside a great grove—

Hay for a headrest

Soil on which to slouch,

A cuckoo calling o’er his hands

Oat grain outstretched o’er his lips.”

Bávlos enjoyed the singing greatly: the woman’s voice, the repeating sounds of the words, the wonderful images she described. Bávlos remembered his many days of sleeping on moors and in forests, both at home and since he had followed Iesh’s call. Tiiu continued.

“Whom should he turn to?

He should make his way to Mary.

She takes the slave onto her shoulder,

Holds him in her hands

Carries him high to heaven,

To the Lord’s lintel

To the lintel of Mary’s chambers.”

Bávlos enjoyed this image as well. Iesh’s mother would carry the poor man upward at the end of life and bring them to a place of rest.

“He sees a golden seat:

‘Sit down here, dear slave!

Long enough you stood in life.’

He sees a light loaf:

‘Eat of the loaf, dear slave!

How you hungered in life!’

He sees a brimming beer mug:

‘Draw and drink, dear slave!

You had but water when living.’"

All worries and cares would be remedied in the next life. All the cruelty would be requited. Bávlos smiled happily at the song. But the woman continued. She sang of a wealthy farmwife and farmer who wanted to finally pay the poor man for his labors. The slave refused, however, ordering his former oppressors into a golden seat of their own:

“’Sit yourself on the golden seat,

While flames flicker underneath it,

A load of firewood fixed to burn.

You will find yourself in the flames

You will be cooked inside a kettle.

You will feel sorrow in the fire,

You will cry inside the kettle!

For you wrung the blood from my body

And you bled me with your bludgeon!

Mighty master, dainty dame

I’ve had enough from you.

Enough, indeed, and then some.’”

The woman finished her song and sighed. Bávlos was stunned. “God will punish them for their evils?” he said.

“Indeed,” said the woman. “Justice will be done.”

They had come at last to the woman’s home. A pack of dogs sprang toward Bávlos, barking wildly. Chickens ranged about the yard in front of the little house that had a roof of straw. Bávlos stooped down to pass through the house’s low door into its dark interior.

The house inside felt warm and snug. It was dark and smoky, and Bávlos was transported in his mind back to his home in the north. As his eyes adjusted to the low light, he began to notice the details of the home. The heat came from a small fireplace that let its smoke into the room. It wafted upward slowly before escaping out a small hole in the roof. There were lofts for storage on either end of the room, and benches and a table across from the fire. Tiiu seemed to move into the area near the fire, as if to underscore that it was the women’s section, just as in a Sámi home. Bávlos felt immediately at home.

“Thank you for bringing me here,” said Bávlos. The woman smiled.

“Ülo!” she cried. Come and meet our guest, a Lapp from the far north!”

“A Lapp?” asked the man, entering the room. “Has a Lapp come to our home?”

“He has!” said the woman. “Our hope is renewed.”

Bávlos ate dinner with the family. Tiiu had brewed a fine beer that they drank gratefully. The couple had a number of children, eight that Bávlos counted for certain, although several were very shy and hardly came to the table. After dinner was over, Tiiu looked intently at her husband.

“Invite him to the ceremony,” she said.

“The ceremony?” asked the man hesitantly. He was significantly older than Tiiu and he rested his large, bald head on one bony, wrinkled arm.

“Yes, he is a keeletarkk Lapp,” said Tiiu. “We need his help.”

“Keeletarkk,” said the man. “You are keeletarkk?”

“I saw it for myself,” said the woman. “He spoke in fluent German to the guard and the priest at the church even though at first he only knew Swedish. And Swedish: where did he learn Swedish? And has it not surprised you that he speaks our language without difficulty? How many foreigners do you know who can do thus?”

Ülo nodded. “I must ask the others first,” he said.

“You do that,” said Tiiu forcefully. “It is our year to lead the ceremony, after all.”

The man quietly rose from the table and walked out of the house. He was gone for some time.

“Help me move the table,” said the woman. Bávlos took the wider end of the table as she grasped its narrower end. They shifted it to the wall. “Now,” said Tiiu, “I leave you. Help our luck, friend keeletarkk Lapp.” Bávlos nodded as she drew a shawl upon her shoulders. She gathered her children around her and in a moment they were all gone. Bávlos was left alone.