Chapter 9. The Church of the Holy Risti

Cultural Explanations

|

Chapter 9. The Church of the Holy Risti Cultural Explanations |

|

|

In this chapter Bávlos visits Hattula church and learns about devotion to the Holy Cross. He receives the Eucharist. Pekka and he part company. |

| Bavlos and Nieiddash at Hattula church |

In this chapter, Bávlos at last enters the populated world of the Swedish-Finland kingdom. He visits one of the most significant churches in the realm and witnesses his first mass. Offered the chance to return to his home in the north, he resolutely refuses, deciding to push forward until Iesh commands him to stop.

By this time, Bávlos has travelled some 900 kilometers (560 miles) over the course of 42 days, an average of 21 kilometers or 13 miles per day. At an average walking speed of three miles an hour, that represents somewhat more than four hours of walking per day. This is an easy pace, but reflects the fact that Bávlos and Pekka have no roads or established paths to make use of, and that they are hunting and fishing as they go. Travel in the remote countryside of medieval Finland would have consisted of walking from farmstead to farmstead, following rivers or traders' paths, and, if possible, making use of boats to cover distances. At this point, however, Bávlos has moved from the remote wilderness north of the Finnish-Swedish border through the dense forests and lake country of central Finland, to the relatively more populated district of Häme (Swedish Tavastland). From Hattula church, there was an established road that led southwest to Turku/Åbo. From here on, Bávlos will be able to make use of roads in his trek southward.

|

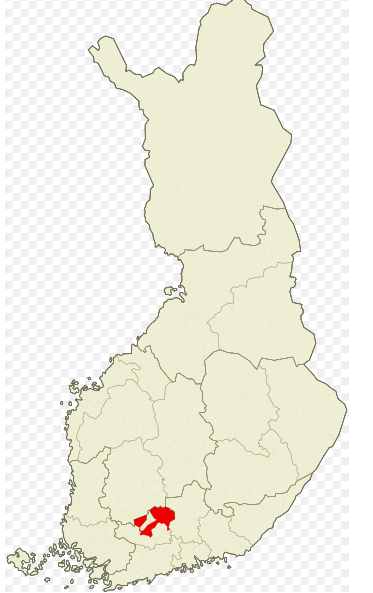

| Hattula.sijainti.suomi.2009.svg (SVG file, nominally 1,850 ?~ 3,220 pixels, file size: 233 KB, courtesy, Wikipedia Commons |

The earliest mention of a church at Hattula dates from 1324, when it became a site of worship for people associated with the royal castle at Hämeenlinna (see image in the cultural information for Chapter 10). The Hattula church of today dates probably from the 1470s and replaced an earlier structure which is now lost. As the images below show, this later brick building announced its possession of a fragment of the Holy Cross dramatically in its architecture. Today, Hattula is well known for its rich medieval frescoes, which probably date from the 1500s. These are works that Bávlos would not have been able to see, although they reflect in many ways the rich legendry with which medieval Christianity was imbued and the abundant use of visual channels as a means of schooling the laity regarding their faith and its greatest saints. Cross veneration was a major devotion in the medieval era, as I describe in my chapter "The Coming of the Cross" in my book Nordic Religions in the Viking Age (Philadelphia: U Pennsylvania Press, 1999, pp. 139-72). For Christians, such fragments of the Cross connected the faithful directly with the pivotal moment in salvation history: the Crucifixion. Further, medieval legendry held that the Cross itself had been made from the wood of the original tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, the tree from which Adam and Eve ate in their fateful Fall. So for Christians of the time, such a sliver encapsulated the entire history of the human race.

|

|

| The Church of the Holy Cross as it looks today. | The church interior, showing frescoes. |

While the famed frescoes at Hattula reflect various aspects of late medieval spirituality, including the story of the discovery and miracles of the True Cross, the church also conserves a great number of wooden sculptures which were probably displayed in the smaller, earlier church. One of these is the "Madonna of Hattula," dating from about 1300. The paint on this statue is remarkably well preserved, and illustrates some of the magnificent ornamentation that graced statues in medieval Europe. Although the sculpture is relatively small (about three feet tall), it would have filled a novice viewer with wonderment because of its fine features, rich colors, and powerful image. Statues like these were central to medieval devotions to the Blessed Virgin, and even after the Reformation, the laity of Finland and Sweden held onto such sculptures as beloved images, ensuring that they were not destroyed in the fervor of the reformers' efforts to cleanse the church of extraneous or confusing devotions. Today the Madonna of Hattula stands serenely against one of the pillars in the church where she was treasured for half a milennium.

|

|

| The Madonna of Hattula; c. 1300 | detail |