Chapter 8. The Skellefteå Mission.

Cultural Explanations

|

Chapter 8. The Skellefteå Mission. Cultural Explanations |

|

|

In this chapter Bávlos learns Pekka's story and uses divinatory trance to find out information about the future. |

| Pekka, Skellefteå, river |

In this chapter, Bávlos learns more about his mysterious companion and his reasons for travelling across Finland. We hear about Pekka's experiences in the new colony of Skellefteå, and we witness Bávlos's divinatory dream regarding Pekka's future and the all-important election that will be held at the priory's chapter meeting.

Pekka shares his understandings of the Christmas story, as seen from a Finnish perspective. The details related here--the wintery weather, Mary's search for a sauna, etc.--are drawn from a cycle of Finnish-Karelian folksongs known as Luojan virsi ("Creator's Verse"). These songs were once apparently common in many parts of the Finnish-speaking region, but survived into the nineteenth century only in the eastern areas of Karelia, where Russian Orthodoxy prevailed as the primary religion. The imagery of becoming pregnant from ingesting a berry, or sauna steam provided by an ox and ass appear utterly Finnish, yet they may also reflect broader European traditions that underwent localization and some honing in Finland and Karelia. You can read versions of Luojan virsi in Matti Kuusi et al. Finnish Folk Poetry: Epic (Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society, 1977).

We learn that Pekka has come from the "Skellefteå mission," far to the southwest of Bávlos's home district. Skellefteå was founded by an edict during the reign of King Magnus Eriksson (1316-1374) as a place for pious Christians to resettle and form a better society. The edict is dated as 1324, and the name Skellefteå (written "Skeldepth") shows up for the first time in Swedish record books in 1327. The ending -eå refers to the fact that there is a river running through the town; the first part of the name probably stems from a Sámi word, although scholars are not sure what word it would have been. At the beginning of the fourteenth century, Skellefteå was inhabited entirely by Sámi, and it was only with the edict that the region began to attract new settlers.

Magnus took the thrones of Norway and Sweden in 1319 as a three-year old, after the death of his maternal grandfather Norwegian King Håkon V Magnusson. The Swedish crown was being managed at that time by Mats Kettilmundsson, head of the Swedish riksrådet (privy council), after Magnus's uncle King Birger had been deposed. Magnus' father, Duke Erik, had died of starvation in 1318, imprisoned by his brother King Birger. With King Håkon's death, however, the regency passed to Magnus's mother Ingeborg and her mother-in-law Helvig and the young Magnus became King Magnus VII of Norway and Magnus IV of Sweden. Ingeborg was a conniving and devious regent, who usually took the opposite side on matters from that of the Swedish privy council, and by 1323 she had become largely stripped of her powers. So it is not clear who really pushed for the settling of Skellefteå: Ingeborg, Helvig, or the privy council. In any case, the edict probably also had economic motives, because the fishing industry was rising at the time, and Skellefteå proved a great producer of salmon that became a major export item of the Swedish realm through the Hanseatic League.

|

| Skellefteå church, and buildings of the medieval parish |

In the aftermath of the New World colonization, we tend to take religious motivations for granted as actual or ostensible reasons for relocating populations to new areas. "Come live a better Christian life with us, away from the corruption and worldliness of the court or city...There's land for the taking and it's meant for us!" In the fourteenth century, however, such a move was novel. Norwegians had undertaken their own entirely secular colonization of Iceland some centuries before, but Swedes had apparently not participated as widely in that process as had Norwegians and Danes. Instead, the efforts of the Swedish crown seemed focused on pushing the Swedish border eastward and--in the Skellefteå mission--northward toward the lands of the Novgorod empire. That Pekka's priory would have been instructed to send some personnel to help in the colony would not seem unusual at all, although we have no records of such a request being made. Dominicans were prominent in missionizing Scandinavia and would have welcomed the prospect of becoming part of the new Christian experiment in the north. On the other hand, Pekka's discomfort at being in a Swedish-speaking environment is also natural: Finnish and Swedish are unrelated languages, and Pekka would have had a difficult time learning Swedish from those around him. The words he uses to characterize his misery--likening himself to a bird in winter drinking cold water--are drawn from Finnish lyric songs, and usually refer to the situation of a bride at her husband's farm.

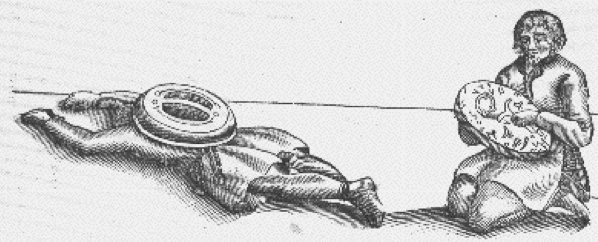

In this chapter we also see Bávlos undergoing a divinatory trance. This is much the same as the one his father attempted in an earlier chapter, but now we see the event through the mind's eye of a noaide in training. The details of the trance portrayed here are drawn from missionary accounts from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries; the notion of flying during a divinatory trance is narrated in many Swedish, Finnish, and Norwegian legends regarding the magic abilities of the Sámi. It appears from such legends that non-Sámi were very aware of Sámi divination and eager to make use of it when they had the opportunity.

|

| Divinatory trance, as depicted in Johannes Schefferus's Lapponia (1673) |

The voting which Bávlos witnesses was a part of Dominican life, as it was in a number of other medieval institutions. The selection of the pope, Swedish kings, and leaders of various monastic orders were all conducted through balloting, although often with all the tendencies toward ballot-rigging and behind-the-scenes meddling that we associate with modern voting. A useful work on the subject is the chapter entitled "Voting in the Medieval Papacy and Religious Orders" by Ian McLean, Haidee Lorrey and Josep Colomer in the volume Modelling Decisions for Artificial Intelligence (Heidelburg: Springer Berlin, 2007): 30-44.