Chapter 7. The Trek Toward Risti.

Cultural Explanations

|

Chapter 7. The Trek Toward Risti. Cultural Explanations |

|

|

In this chapter Bávlos learns more about Iesh and the story of his life as he travels south with Pekka. |

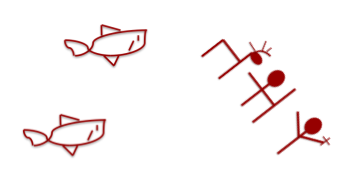

| Fish, Nieiddash, Bávlos, Pekka |

In this chapter, we see Bávlos learning more about the religion and culture of his companion.

The chapter depicts a little of the actual hard work Bávlos is going through in order to learn Finnish. Even though Finnish and Sámi are related languages, they differ greatly in grammar and vocabulary, as Bávlos discovers. If learning a new language were simply a matter of learning one new word for every old word one has in one's native language, the job of language learning would be irksome, perhaps, but not terribly difficult. Instead, however, each language is more than simply a list of vocabulary and rules for pronunciation. It is also a way of looking at the world and a set of strategies for expressing thoughts. Finnish is a highly agglutinative langauge, which means that instead of using prepositions, as in English, it tends to use suffixes added to the word. So, as Bávlos learns, the word for a sweat-bath sauna, can be modified by adding a great number of endings: saunahan (modern Finnish saunaan) means "into the sauna," while saunassa means "in the sauna" and saunasta means "out of the sauna." Northern Sámi has some such case endings, but far fewer than Finnish, and thus, Bávlos finds the new language amusing and quirky. Learning to speak this new language entails learning to think in a new way, and Bávlos finds that intriguing and enjoyable.

On the other hand, Northern Sámi has, in addition to singular and plural forms of verbs, also a dual form. So one can say boaðán ("I come") and boahtit ("we come") but also bohte ("the two of us come"). The form boahtibeahtti means "the two of you come," while the form boatiba means "the two of them come." For whatever reason, speakers of Sámi saw a need for expressing the dual in their daily speech, and this need became met in distinct forms of the verb. Interestingly, a number of other languages in the medieval far north also had duals, including Old Norse and Greenlandic (Inuit). For Bávlos, then, learning a new language means setting aside an important category that he has always taken for granted. If such great differences occur between related languages like Sámi and Finnish, imagine the work it will be for Bávlos to learn the languages to the south and west of the Baltic sea. Luckily, Bávlos has confidence in his supernatural gift for learning languages and is not worried about the prospects at all.

As Bávlos moves into the Finnish-language region, he also begins to see a new landscape.

|

| Birch forest in northern Finland |

In the north of Finland, in the area while Sállevárri lies, the tree growth is sparser and smaller. Trees (primarily birch) do not grow as tall, and there is often a good deal of open space between them. This vegetative pattern gives the landscape an open feel, one which Bávlos has taken for granted in his life. Somewhat farther to the north, the trees stop growing nearly entirely, and the landscape becomes dominated by tundra, a word that comes from Sámi duoddar, borrowed into Russian as tundrá and from there into English.

|

| Pine and birch forest in southern Finland |

In central and southern Finland, in contrast, forests are thicker, with taller pine, spruce and birch trees and a faster growth of vegetation in general. These differences make for a very different perception of the landscape, and affect things like hunting and hiking. Bávlos notices these facts as he walks southward with his companion.

The tendency to imagine the Savior speaking in one's native language is a normal one and recurrent throughout medieval Europe. Although clergy learned Latin to some extent, they seldom had much of a notion of the Greek and Aramaic that Jesus actually spoke, or the meanings of the Hebrew and Aramaic phrases quoted in various biblical passages. Pekka, as a lay brother with little book learning of any sort, has tried to make sense of the words he has heard in sermons and Gospel readings from his own point of view. Thus, he perceives Christ's utterances as Finnish, while to Bávlos, they eventually appear Sámi. The sentence that Bávlos recognizes in the biblical "Eli, eli, laama sapaak tani" (Pekka's oral rendering of the line usually written as Eloi, eloi lama sabachthani; Matthew 27:46, Mark 15:34) is actually a Greek transcription of an Aramaic utterance, possibly itself a translation of a Hebrew psalm. You can read more about its meaning on this interesting Wikipedia page. Bávlos's understanding of the words as “Elle, Elle, leaba mu sábet dávvin—‘Elle, Elle, my skis lie to the north’ illustrates again the use of the dual: leaba means "the two of them are" and refers to the two skis (sábet).