Part III. Italy

Chapter 55. Arriving in Assisi [May 7, 1348]

Cultural Explanations

|

Part III. Italy Chapter 55. Arriving in Assisi [May 7, 1348] Cultural Explanations |

|

|

In this chapter Bávlos learns more about Francesco, receives the stigmata and heads back to Siena. |

| Assisi, Francesco with Stigmata |

In this chapter, Bávlos at last reaches Assisi, the home of St. Francis of Assisi. Here he stays at the immense Franciscan priory alongside the grand Basilica built in Francesco's honor. With his friend Giovanni as his guide, he visits the various sites of importance to the life of the saint and his order.

|

|

|

Bávlos meets a friar Ugolino, who has reportedly completed a book regarding Francesco. This would be Ugolino di Monte Santa Maria, who finished his work Fioretti di San Francesco (The Little Flowers of Saint Francis) around 1330 and is known to have been still living in the 1340s. A good English translation of the work is by Raphael Brown (NY: Doubleday, 1958). Ugolino's work gives us a vivid picture of the stories in circulation among Franciscans in the early fourteenth century concerning their holy founder and his original disciples. Ugolino lived in the neighboring region of the Marches, but is depicted in this chapter visiting Assisi.

|

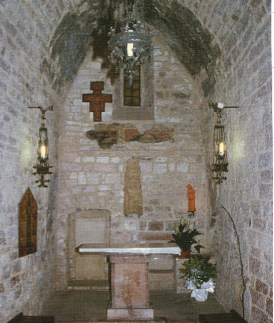

| Oratory of San Francesco Piccolino |

In the chapter, Ugolino shows Bávlos Francesco's boyhood home and the small room in which he was born.According to his vita and local Assisi tradition, Francesco was born not in his merchant father's house but in a modest storeroom, now a chapel called the Oratory of San Francesco Piccolino. Here it was that his French mother Pica came to give birth when her labor was delayed in the grand house of her husband. Bávlos takes "French" to mean anything north of Italy, including (or especially) the lands of the Sámi. The fact that Pica's name means "servant girl" in Sámi (a loan word from Norwegian or Swedish) confirms for Bávlos the idea that Francesco was actually a displaced Sámi, like himself. Although the oratory was preserved, Francesco's house was later subsumed into a grand church, the Chiesa Nuova, and only some portions of it remain, including Francesco's boyhood room and the small space under a staircase where Francesco's father imprisoned him for a time to try to break his son of his love of poverty.

|

|

| Small roadside chapel on road out of Assisi, headed for San Damiano | The countryside of Umbria as viewed from Assisi |

The countryside around Assisi is rich in agriculture, dotted with vineyards and olive groves. The seasonal laborer could find ample work in the fourteenth century, and Bávlos is immediately drawn to the life which Francesco led with his followers.

|

|

| The Convent at San Damiano | The Priory by the Basilica of San Francesco |

The original church that Francesco repaired, San Damiano, remains a monastery today. Francesco eventually gave the space to the female Franciscan order led by his follower Santa Chiara (St. Clare). The "Poor Clairs" remain in the monastery today. The main priory of Franciscan friars today is located alongside the Basilica and is much grander. It is here where Bávlos spends his nights.

|

|

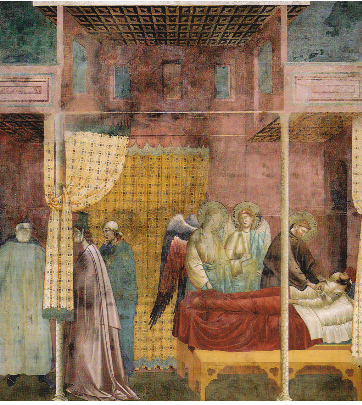

| Giotto's fresco showing Francesco's curing of the throat and shoulder wounds of one Giovanni. | Giotto's fresco showing Francesco cradling the animated infant Jesus that he had carved to help edify the laity. |

Bávlos is moved by several frescoes he observes. One depicts the curing of a man with a severe throat wound. The other depicts Francesco's creation of the first Nativity Scene, a sculptural tableau meant to convey the simply message of Christmas to lay churchgoers. According to legend, Francesco's carved infant Jesus came alive in his arms.

|

|

| Francesco receives the Stigmata. |

One of Francesco's most famous attributes is the Stigmata, recapitulations of the wounds which Christ was said to have received on his palms, feet and shoulder during the Crucifixion. Numerous Italian saints after Francesco were also credited with receiving the Stigmata, including St. Catherine of Siena (whose stigmata were invisible) and the recently canonized twentieth-century saint Padre Pio, whose bloody hands were a frequent feature on pious Catholic calendars throughout Europe in the years before his death.