Chapter 4. The First Steps.

Cultural Explanations

|

Chapter 4. The First Steps. Cultural Explanations |

|

|

|

In this chapter, we get to see Sieidi from an unsympathetic outsider's view, in which his very sacrality is summarily dismissed. This experience was repeated over the centuries for Sámi people as Christianity made inroads into the culture and called into question the ancient means of worshipping and securing luck.

Sieiddit were naturally occurring stones or carved wooden images that Sámi believed helped control luck of various kinds. Making an offering to a sieidi could ensure success in hunting, fishing, trapping, marriage, or other important undertakings. In the story so far, we have seen Father and Sálle in their reverent treatment of the fishing sieidi located near their home. Now this sacred object comes into the view of a Christian and is derided as a powerless idol.

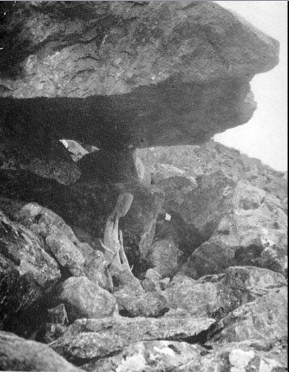

Sámi sieiddit were largely abandoned in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries as sites of worship, but many remained known to local Sámi communities for much longer and some still remain in the landscape in the places they occupied for centuries before. Sámi today still regard the sites as sacred, and may refrain from loud talk or other disrespectful behavior when in their vicinity. A tradition also warns against taking any object left by past worshippers for the sieidi. Here are some images of surviving sieiddit, some now in museums, some remaining on the land.

|

|

|

|

Pekka's earnest explanations of his own object of worship may reflect his lack of cultural sensitivity, but they also make clear the sincerity of his beliefs. As he attempts to explain the basic tenets of Christianity to Sálle, we see the Christian worldview as it would have been interpreted from a pre-Christian Sámi point of view. The mysterious chief deity Jumala (Finnish for God) Sálle interprets as the sun, the most important supernatural being in the Sámi cosmos. Sálle regards the friar's crucifix as a portable sieidi and admires the ingenuity of making the sacred being small and light enough to be carried along on one's travels. Sámi always needed to return to the sieidi where it was lodged in the landscape and always ran the risk that it might be discovered by others and possibly vandalized or desecrated, particularly during the era of missionization.

Sálle has trouble understanding a number of other words in the friar's explanations as well. He takes Abraham for ahparash, the unhappy spirit of a murdered infant. Later, he hears Abraham as áhpespálfu, the North Sámi word for the European storm petrel, Hydrobates pelagicus.

|

Image courtesy Wikipedia commons http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Hydrobates_pelagicus.jpg |

Neither of these associations are particularly positive: the ahparash was a much-feared specter that haunted the byways where the infant had been murdered. The stormy petrel tends to appear just before storms at sea and was thus regarded as an ill omen. Sálle's encounter with the friar illustrates the considerable challenges that faced missionaries in northern Europe, as elsewhere, as they sought to spread news of Christianity among the populace. In the end of the chapter, tellingly, Sálle has confidently subsumed his companion's religious system into his own and has now decided to help shepherd the friar toward proper religious behavior.