|

As with many activities in life, Sámi religious duties were largely segregated into a male sphere and a female. Male rituals generally took place outside of the home at particular sacred sites where statues or natural objects were located that Sámi associated with the maintenance of luck and health. These sieidi sites were sometimes oriented toward hunting or reindeer luck and sometimes devoted to fishing luck. In this chapter, we see Sálle visiting the site of his family's fishing sieidi, where it stands in a marshy area at the confluence of two local rivers. Sieiddit of stone or wood were rubbed with fish fat as an offering for continued luck. Sometimes they were said to have twins which were submerged in a nearby lake or river, and which helped create or guarantee the fishing luck which the Sámi hoped for.

Sálle has been named for his grandfather, who was the family's key leader of sacrifices and securer of luck. A noaide (shaman) received his supernatural abilities through the assistance of a "spirit gang" of powerful unseen spirits, consisting of deceased former shamans, other dead, and certain animals. Since Sálle is the member of his generation whom the family regards as the most likely future noaide, it is his task to make these offerings. As the chapter illustrates, however, Sámi believed that it was the spirit gang who chose the future shaman in their own way and on their own terms. The family must wait until the spirit gang makes contact with one of their members and offer the honor and responsibility of becoming the next noaide. |

|

The Sámi home--goahti--was a rich center of daily life and ritual as well, and was presided over by the woman of the house and her daughters. As can be seen from the photo here, taken at the Siida Sámi museum in Inari, Finland, Sámi houses in this area often consisted of a combination of wood, bark, and turf surrounding a central hearth and open smoke hole. They were round in shape, with very particular areas for visitors, men of the household and women. Women occupied the area behind the hearth, opposite the doorway. Men occupied the areas to the left and right of the hearth. The area directly by the door was where guests could sit when they entered the house. In this and coming chapters, the characters observe these rules of space meticulously.

|

|

|

|

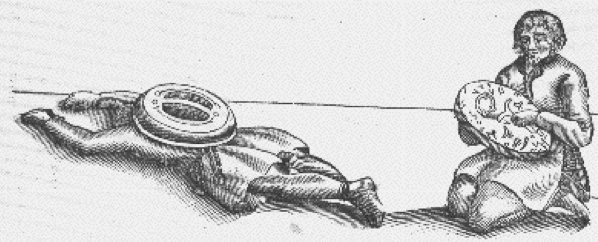

The household was also presided over by supernatural women: the "Old Women" who appear in Mother's divinatory dream. Eighteenth-century accounts of Sámi religion describe a mother goddess Mattaráhkká, as well as three daughter goddesses. The first of these, Saráhkká, was said to dwell beneath the hearth. She aided in women's pregnancy and maintenance of good fortune in general. A second daughter, Juksáhkká presided over men's hunting weapons, which were always stored in the men's part of the goahti and could only be touched by women at certain ritual moments. She is often depicted with a bow. Juksáhkká took care of fetuses that were destined to be male and helped ensured their hunting and fishing luck. A third sister, Uksáhkká resided beneath the door to the goahti and guarded the household against dangers from the outside. It was the duty of women in the household to keep on the good side of these spiritual allies and enlist their aid for themselves and their families. The picture to the left shows several different versions of how the three sisters were depicted on shamanic drums of the eighteenth century. Image courtesy Sámitour website. |

This chapter also depicts Sámi courtship and the ways in which marriage partners were chosen in Sámi life. As we see in the chapter, Sámi marriages were regarded as both individual and familial relationships. It was important for a woman and man to be interested in each other and compatible in temperament. At the same time, marriages were a means of former important alliances with other families, and parents thus often took a strong interest in helping shape the matches that were most advantageous for their families.

Against this highly structured and predictable system of courtship, the family in this chapter is depicted worrying about possible bride theft from one of the birkalachat or other strangers. Mother avers that strangers could steal women to eat them: this belief was connected with a particularly menacing being called stállu, who figures as a kind of half-troll/half-man interloper who often attempts to capture Sámi as marriage partners or dinner. No one knows exactly who the original stállu characters were, but scholars suggest that such beliefs may have stemmed from animosity and fear among Sámi regarding the cultural outsiders who were making inroads into the region during these centuries. |

|

|

|

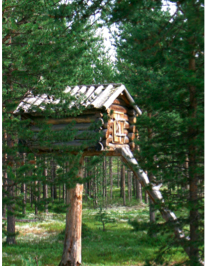

The family hides Elle in one of its njalla storehouses. These structures resemble a small cabin perched atop a tree trunk and were designed to protect stored meat, fish, or other goods from hungry animals who might be attracted by the odor of the food. Because Sámi travelled to various areas in their tracts over the course of the year, they needed secure structures in which to store their provisions. Such a structure would represent an ideal place to keep a daughter safe from a unknown and possibly dangerous outsider. |

|

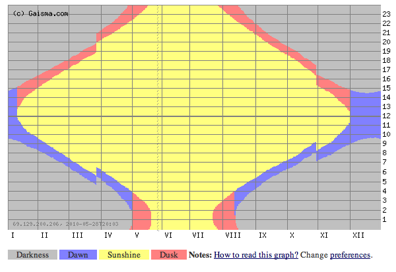

| You can see the daylight regimen for the area of Inari by clicking HERE. The graph from Geisma's fine website is reproduced to the right. Short periods of dusk begin to recur in the second half of July, but the days do not really begin to shorten markedly until August. |

|

|

|

The stranger who arrives in this chapter, Pekka, is a Dominican friar. His clothing--a white robe with a black cloak, sandals, and a rosary--was typical for his order. His hair has been cut into a tonsure, a characteristic mark of religious vows in the medieval period. The Dominicans were very important in Scandinavian Christianity, particularly in Finland, where the order played a central role in the spread of the new religion. |

|

| Finally, Sálle describes himself as gielládárki. This concept was part of Estonian oral tradition regarding Sámi, and figures in the Estonian national epic, Kalevipoeg, where one of the characters is Sámi. Although the idea of supernatural skill in language was not apparently a part of Sámi beliefs about themselves, it is certainly true that Sámi learned to communicate in many of their neighbors' languages, while their neighbors seldom learned any Sámi language in return. Throughout the novel, Sálle learns a host of foreign languages with greater or lesser success. The discussion depicted here features northern Sámi and Finnish. Pekka states: Minun pitää kaupunkihin, which is a somewhat old fashioned-sounding way of saying "I need to get to the city." Sálle recognizes the word kaupunki as a cognate of the Sámi gávpot and guesses the stranger's request. So the two are communicating, but perhaps not with the degree of mutual comprehension that the supernatural term gielládárki would imply. |

|

|

|

Depiction of Sámi drum divination from Johan Scheffer's

Lapponia (1673) |

|