Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348

a free multimedia novel by

Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison

|

Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348 a free multimedia novel by Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison |

|

|

|

|  |

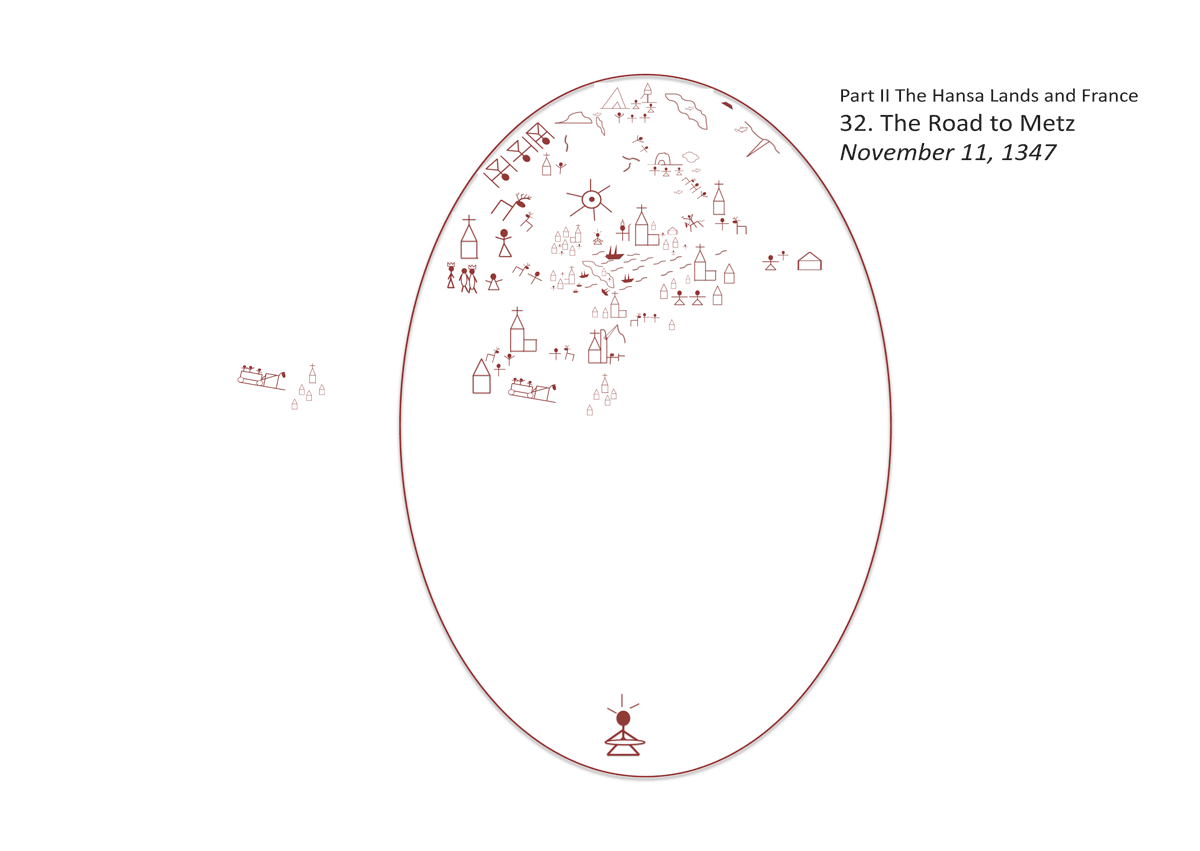

32. The Road to Metz (November 11, 1347)

And the Lord said to Satan: "Behold, all that he has is in your power; only do not lay a hand upon his peron." So Satan went forth from the presence of the Lord. s

The next day dawned bright and sunny. The teamster rose early and was busy strapping on his belt and jacket when Jacques awoke.

“Monseigneur the teamster,” said Jacques deferentially. “Did I understand right last night that you are headed for Metz?”

“That I am, boy,” said the man. “What of it?”

“Well,” said Jacques quickly. “Can you take two riders? I can sing and tell stories to pass the time!”

“I bet you can,” said the man, glancing at the boy’s cithole. “All right, sure, meet me at the stables within the hour!”

“We shall be there!” said Jacques, shaking Bávlos awake.

“Bávlos!” he said, as the man left the room, “we have a ride all the way to Metz! Can you imagine?” Bávlos had no idea where Metz was, but he was glad to know that they would be making progress toward Paris. Jacques did his share of performing that morning. The teamster, a quiet man named Bertrand, did not seem particularly picky about what his passengers said or did, so long as they spoke. Bávlos had the feeling that this man must find the teamster’s life very lonely and he wanted company on the road.

“Does Metz also belong to the land of Lëtzeburg?” asked Bávlos.

“Not hardly!” grunted Bertrand, “and you had better be careful what you say about that in Metz! The old Duke Jean tried to capture Metz some twenty years ago, when he teamed up with the Duke of Lorraine. But Metz held out.”

“Duke Jean?” said Bávlos, “I thought he did all his fighting against the distant pagan Lithuanians, or to the west, in Crécy? It was a Lithuanian who put the curse on his vision, was it not?”

“Yes, well,” said the man grouchily, “there were many in Metz at one time who would have gladly cursed his sight as well!”

“Ah, said Bávlos, “I had heard he was good.”

“Folk can be good sometimes and bad at other times,” said Bertrand. “It is the struggle of the angel and well, you know who.”

“Ah,” said Bávlos. He had no idea what Bertrand meant.

“This language we are speaking,” said Bávlos, later that morning to Jacques, “this language you speak; is it spoken all the way down to Avignon?”

“No, no,” said Jacques, shaking his head. “To the south they speak Oc and beyond that Lombart and Espagnol. To the west they speak Breton. To the east, as you know, they speak Alemant, the Hanze speech, and to the northeast they speak Norment. He sang:

“François, Breton et alemant,

Lombart, anglois, oc et norment,

Et meint autre divers langage,

C’estoit a oďr droite rage!”

French, Breton and German too

Lombard, English and Norman true,

And many another tongue

To hear them is such fun!

“We are only an island here who speak the language of Oďl” he said.

“It is a beautiful language, though,” said Bávlos.

“It is,” said Jacques, “and you are learning it tolerably well.”

“Can you teach me,” said Bávlos hesitantly, “can you teach me the prayer that folk use when speaking to the mother of the Savior?”

“To la Vierge?” said Jacques, “But of course! I can teach it to you in Oďl and in Latin!”

“You can?” said Bávlos, his eyes widening. He felt very lucky indeed to have come to know such a learned jugleur, and one who was so young.

“It starts like this,” said Jacques: “Ave Maria gratia plena. But in Oďl, we say it thus: Je te salue, Marie, pleine de graices.”

“And what does that mean?” asked Bávlos.

“Ave,” said Jacques, pausing to think, “this is the opposite of Eva, the name of the woman who brought us to sin.”

“Eva?” “Yes, the first woman,” said Bávlos. “God told her not to eat the apples from a tree but she did anyway and then everything was ruined. God sent her and her husband Adam out of the garden and we have been in misery ever since.”

“Why did she eat this apple?” asked Bávlos. He suspected she must have had some reason for doing so, perhaps hunger.

“It was the serpent that tricked her into it!” said Jacques. “Do you not know this story? It is pictured in nearly every church in France!”

Bávlos thought it strange that a snake would have been so devious. As far as he knew they never ate apples themselves, at least if an apple was some sort of fruit, as he guessed it was. Among the Sámi, snakes never spoke to people, but when they did, they were often sources of good luck or healing. If snake venom was wiped on the hand it could make the hand a tool for healing ever after. Of course, Bávlos reflected, there were many more snakes in this land than back home, and perhaps these people knew better what they were really like. Bávlos noticed that people generally tried to kill snakes here whenever they saw them. “All right,” said Bávlos. “So first we reverse Eva’s name.”

“Yes,” said Jacques. “That is what the Angel Gabriel did when he came to Marie.”

“The Angel Gabriel?” said Bávlos.

“Yes, a messenger from God,” said Jacques. “He had great wings on his back but he hid them so as not to frighten Marie.”

Bávlos nodded. He remembered having heard of the winged spirit helpers of the strangers. Gabriel must be one of these. “Ave Maria, gratia…”

“Gratia plena,” said Jacques: “pleine de graices. This means that Marie was pleine,” he said, motioning to his stomach, “she was expecting a baby. And graices, this means good help, favors. You see, the angel is telling Marie that she is pregnant with the son who is all good things.”

“Ah,” said Bávlos. “And then the angel explains what he means to Marie. He says Dominus tecum. Le Nostre Sire est avec toi.”

“Aha,” said Bávlos happily. He recognized the word Dominus from what Pekka had taught him. It was another word for God.

“Benedicta tu in mulieribus,” continued Jacques, “Tu es benoîte entre les femmes. This means that of all the women, Marie is benoîte, this means ‘happy, lucky.’ She is the happiest of all women because she is the mother of our Lord! Et benedictus fructus ventris tui, Jesus. Et benoiz est li fruit de ton ventre, Jesu Christ Nostre Seigneur. This means that the fruit of Marie’s womb is a happy thing, because it is Our Savior!”

“Ah,” said Bávlos, “a fruit again.”

“Yes,” said Jacques. “But the angel is telling Marie that the fruit that she will give is much better than the fruit that Eva had given: it is our Savior.”

“So that is the prayer that one says,” said Bávlos thoughtfully.

“Always,” said Jacques, nodding. “One can say it always, and everywhere. I say it fifty times a day if I say it once!”

“Yes?” said Bávlos. “

Yes,” said Jacques. “There are other prayers, too, like the Pater, but these are longer and harder to say quickly. So most people say the Ave when they need God’s help right away. I have heard of people saying it when falling out of a tree and saving themselves from broken bones by doing so! And most people say it before doing anything of any importance or danger.”

Bávlos was delighted to learn this prayer and looked forward to learning the Pater Noster as well as soon as he could get the Ave straight in his head. Bávlos noticed that Latina and Oďl were really quite similar in many respects. Both languages seemed to have the same obsession with whether something was a man or woman that he had noted in Swedish, as well as in the Hanze speech. It just seemed crucial in these regions to remind people constantly that Iesh was benedictus or benoiz, “happy in a man’s way,” while his mother was benedicta or benoîte, “happy in the way of a woman.” Why they couldn’t both be simply “happy” he did not know, but Bávlos noticed that Jacques divided the entire world into these two categories. Everything for him was either a man or a woman, including sticks, mud, trees, clouds, water, dung, and sweat. Jacques was always certain about which any given thing would be, and he always smiled or snickered if Bávlos misremembered it. Still, it was hard to be irritated with someone as happy as Jacques or as ready with a song or story.

“Do you sing?” Jacques asked as they ride continued.

“Of course!” said Bávlos. “Where I am from, everyone sings all the time!” He thought it strange but somehow characteristic of Jacques that he had never asked this question until now.

“Sing us a song, then!” said Jacques. “I will learn it.”

“All right,” said Bávlos eagerly. “Here is the song of my sister Elle. He leaned back, closed his eyes and began to wharble a joik in a loud, energetic voice that rose up and down quickly and made the horse’s ears flatten backwards in irritation:

“Good at sewing, good at cooking,

Elle Maija’s handsome daughter, lo, lo, lo…”

Jacques stared. “This was singing?” he asked in a shocked voice. The teamster chuckled and shook his head.

“Yes, of course it is a song!” said Bávlos grinning in embarrassment “That is how we sing in my land. There are not many words, but I can tell you that this song reminds me exactly of my sister as I remember her.” He felt a little homesick thinking of her. What was she doing now? Had Aslat come to court her after all? Were they planning to marry? Were they waiting for him to return? His musings were interrupted by Jacques’s persistent chatter:

“But the melody,” said Jacques, sputtering, “it was just a string of completely unpredictable sounds! And the rhythm—what was it? How could someone dance to this song?”

“I don’t know what you mean,” said Bávlos defensively. “I sang Elle’s song as I have always done.”

“Please,” said Jacques quietly, “in the future, let me do the singing.”

“Just as you wish,” said Bávlos. “People here don’t know my sister anyway. Let them hear about your ladies with the rose red lips.”

The day was cool but sunny and it felt pleasant to sit in the back of the wagon, watching the road. Nieiddash plodded happily along behind the wagon, tied with a line but free of her packs. She seemed to enjoy being in a line with another draft animal again: reindeer always prefer to walk in a line, Bávlos reflected.

As they were riding along, Bávlos took to looking at the wheel of the wagon as it turned round and round. This was the first wheeled vehicle he had ever ridden in, although he had seen lots of wagons in Sweden and the Hanze cities. How like himself the wheel was—always turning, always contacting the earth to move forward in rotation after rotation after rotation. Always repeating himself. He reflected on the long, long way he had walked to this point: the month in Finland, the weeks and weeks and Sweden and the German lands. Now on to France. Where would it end? When would Iesh say “Stop!”

Suddenly, Bávlos had a strange sensation. Just as he had said “stop” in his mind, he had looked up to check on Nieiddash as she plodded along behind. And just at that moment—indeed, at the very moment he had said “Stop!,” the wagon wheel had seemed to stop for an instant. It had looked clear and sharp and frozen in place, as if it hadn’t been moving at all. Now, however, it looked blurred, no details of the rim particularly clear as it turned round and round in its endless progression. Why had the wheel suddenly frozen? Was this a sign from Iesh? He looked intently at the wheel again and said “Stop!” Nothing happened. The wheel did not freeze at all. “Strange,” said Bávlos aloud.

“What is strange?” said Jacques, looking over at him. He had been lying on his back, looking at the sky. Now he sat up and looked over at Bávlos.

“I said stop in my mind and it looked for an instant like the wheel actually stopped!” said Bávlos wonderingly.

“Let me see,” said Jacques eagerly, “You say you said stop—“ he said, looking up at Bávlos. “Hey! I saw it! When I said ‘Stop!’ the wheel stopped as well! But only for an instant and it didn’t seem to actually occur—at least, I didn’t feel the wagon actually stop in any way.”

“I tried it again,” said Bávlos, “and it didn’t work for me a second time. Let me try once more.” Carefully he stared at the wheel and said aloud, “Stop!” There was no change. Inwardly, he thought that the wheel seemed to stop if he said the word in Sámi, Bisan, while it seemed to work for Jacques when he said it in his own language: arrets-toi. Perhaps the wheel did not approve of foreign accents? He glanced up at Jacques to share his views and suddenly, for an instant, he saw the wheel freeze again. “It happened again!” he cried, “But only when I was glancing away from the wheel, not when I said ‘Stop!”

“When you were glancing away?” said Jacques. He tried it as well. Carefully he stared at the wheel as it turned then he looked away at the side of the road. “I saw it!” he cried. “This is most strange!”

“Have you ever seen anything like this?” asked Bávlos. It was, after all, his first time in a wagon, and he had no way of knowing what was typical or unusual of the event.

“I have ridden in wagons many, many times,” said Jacques with great seriousness, but I have never, ever seen such a thing. I think you must have bewitched the wagon, Paul!” He looked at his companion with his eyes wide. Bávlos could detect a glimmer of panic in them.

“Nonsense,” grunted the driver from the front of the wagon, not even bothering to turn his head. “Every driver in Luxembourg knows of that oddity. When you look fixedly at the turning wheel it is a blur, but when you turn away, it seems to freeze for a moment.”

“What is it that does this?” asked Bávlos with excitement.

“The devil,” said the driver, crossing himself. “It is the work of the evil one.”

“The devil?” said Bávlos. He had heard references to this being before but had never figured out who he was. He seemed to be someone that everyone already knew about, and Bávlos was a little afraid to let his ignorance show. He decided to ask a fairly general question: “The devil does such things?”

“Of course he does,” said the driver intently. “He wants to deceive human beings every chance he can get. So he blurs the view of the wagon’s rim while we are looking at it, just as he blurs our understandings of right and wrong when we are thinking about them carefully. But as soon as he sees that we are turning away, he stops the enchantment and turns his mind to some other deceit. And then we see that wheel as it really is, but only for an instant.”

Jacques nodded thoughtfully. “I have never realized how artful the devil is,” he said. “He must be watching our every move.”

“Our every move,” said the driver gravely. “Always deceiving, always deceitful.”

“But why?” asked Bávlos innocently. He realized as he said the words that his question might attract some suspicions from his Christian companions.

“Why?” said the driver intensely, “Why? Because he wants to lead our souls to Hell, that’s why!”

“Hell?” said Bávlos uncomfortably. He was aware that what the driver was telling him was very important, but he had no idea what he meant.

“My friend is a foreigner,” said Jacques to the man, “He doesn’t know our words for things. Hell—” he said to Bávlos patiently, “is what we call the opposite of heaven, the place where God sends the people who have not lived good enough lives to pass into paradise.”

“Ah,” said Bávlos. Pekka had told him about this place—helvetti, he had called it. It was a place of perpetual torture and misery, always cold, always dark. “The unhappy dark and cold place,” he said.

“The hot, burning, blinding place!” said the driver. “Where the evil of his world are fried like sausages, and made to kiss the devil on his bottom, and forced to bite themselves, and stewed in a pot, and choked on terrible odors, and made to watch their entrails pulled out and wound around spinning wheels forever!”

“Oh!” said Bávlos. He felt very anxious now. “And you say that this devil is playing this trick on our vision when we look at the wheel?”

“He is!” said the driver. “I learned it so from my father when I was no older than this lad here,” he said, gesturing at Jacques. “You see, it’s like this. The devil is constantly trying to fool us. To make us see things other than they really are. Then, once we are used to his deceptions, he can convince us to do evil things and think they are fine. And foolish, innocent people go along with his ploys until their dying day. And on that day, their evils are revealed to them as they really are, and God punishes them as they deserve.”

“Unless Mary intervenes?” said Bávlos, thinking back to the play he had seen when he had first arrived in Visby.

“Yes,” said the man, nodding eagerly. “Nostre Dame,” he said, calling her by her exalted title in French, “she can plead on our behalf and Christ may relent for her sake.”

“But when we see the wheel stop—“ said Bávlos. He still didn’t quite see how it fit into this account of the workings of the devil.

“When we see the wheel stop,” said the driver, nodding patiently, “my father used to say that it is because the devil ends his enchantment and we see the wheel for a moment as it really is. But I have been a drover now for many, many a year. And I have a different theory about that vision.”

“You do?”said Bávlos. He was very interested in the man’s account and the fact that he had called this glimpse of the wheel a “vision.”

“I believe,” said the man, “that when we see the wheel as it really is, it is a sign from our guardian angel—a message. It is the angel’s way of saying ‘See here, man, this is the real way of things. Do not believe in the devil’s wiles but know that he is trying to deceive you, to bring you to your demise.”

“Ah,” said Bávlos. “It is a message from the guardian angel.” He wondered who the guardian angel was. Jacques seemed to notice his confusion again and came to his aid:

“The guardian angel,” he said, “is what we call the angel that is with you every moment, the angel that saves you from dangers and tries to lead you to heaven.”

“Ah,” said Bávlos. “So that’s it!” He smiled at his companions so as to hide his confusion. Jacques seemed delighted by the man’s words. The man, too, seemed happy at having his theory so warmly received. “But this angel,” Bávlos said uncertainly, “he can only reveal the truth about the wheel for a moment?”

“Yes,” said the driver gravely. “Our vision is clouded by the sin of Eve. We are destined to see things as the devil distorts them for us. But every so often, just so that we have a taste of the truth, the guardian angel overpowers the devil’s enchantment and lets us see the truth. But I think, “ he said, pausing to think about the matter a little further, “I think that the guardian angel must not be able to achieve this disenchantment when the devil is fully aware: I think he must wait to catch the devil off guard, as when he thinks we are turning away.”

“I see,” said Bávlos thoughtfully.

“You are a wise driver!” said Jacques in admiration. “I shall sing you a song!”

“The Holy Michael angel on high,

with sword and helmet he strove,

the evil devil let out a cry,

him from heaven the angel drove!

Now deep below the green, green earth

The devil torments the damned,

We have been saved by our Savior’s birth

From that realm with sinners crammed.

Kind Michael, angel great and brave

Hear our humble cry!

From the wiles of the devil do me save

That I may rise up on high!”

As Jacques finished singing, Bávlos fell to looking at the wheel again. Indeed, every time he glanced away from it, he seemed to see it stop in place. He reflected on what the driver had said. Who was this devil that was so intent on leading people to ruin? And who were these guardian angels trying to counteract him? What did the driver mean by the devil distorting the world we see? Had the devil distorted his view of the world at all? He couldn’t think of any instances, but perhaps they were so subtle that he had not noticed them. And who was this guardian angel? It seemed to Bávlos that he must be part of his spirit gang, but how come the driver acted like there was only one such guard, when Bávlos knew for a fact that his gang had many members—not only Iesh and an undetermined number of dead kin, but also an increasing number of Christian spirits as well, including Nostre Dame and the Holy Risti. Had the angel Gabriel been Nostre Dame’s guardian angel? And who was the angel Michael?

Another question troubled Bávlos as he rode along toward Metz. Just what did this drive mean by saying that helvetti was hot? When Pekka had talked of this place, he had been clear to say that it was cold and dark, and Bávlos had recognized it as the place called Jápme-aimuo, the land of the goddess Jápme, who was death herself. Bávlos had always heard that Jápme-aimuo was a fairly pleasant and relaxing place, even if dark and rather cold. After all, a place deep within the earth could hardly be expected to be bright or particularly warm! Bávlos had come to understand that Iesh’s kingdom in the sky was far superior to Jápme-aimuo, and he had been excited to journey there, especially since all his kin seemed to have reached it already. But this driver seemed to be suggesting something very different: Jápme-aimuo seemed tortuous in his telling, and it seemed hot and firey as well. This made little sense to Bávlos: how could a place filled with fire ever be anything but pleasant? Was the sauna not a glorious place, especially when heated to a burning temperature? How could the devil sustain these fires in his land? Did he have an endless supply of trees to burn? And why did this devil take such pleasure in harming people anyway?

As Bávlos pondered these questions, he paused to look up at the driver. He was patiently sitting on his seat at the front of the wagon, holding the reins and speaking every now and then to the large brown horse that was pulling them along. Suddenly Bávlos realized the answer: this helvetti was not Jápme’s land but rather Rut-aimuo, the land of the evil Ruto! Bávlos shuddered at the very thought. Ruto was a fierce adversary: a dark and evil marauding spirit who always arrived on horseback and brought disease with him to kill all who were unequipped with powerful defensive magic. Ruto would be the sort that would disguise the wagon wheel’s appearance so as to hoodwink good people: in fact, Ruto would stop at virtually nothing to ensnare victims for his kingdom. Bávlos had always heard that the land Rut-aimuo was an even darker place than Jápme-aimuo, since it lay far deeper in the earth. But perhaps these folk around here knew Ruto better than did the Sámi: after all, they used horses as a part of daily life, like Ruto, and Ruto was known to be foreign and evil. It must be that he was from somewhere hereabouts.

“Is there anything called ‘Ruto’ you know of that is associated with horses?” said Bávlos cryptically. He wondered if the name Ruto would turn out to be another name for the devil.

“Ruto?” said Jacques, thinking, “I don’t think so,” he said.

“What’s the matter with you, boy,” said the driver again, turning to glare at Jacques. “The rateaux are the things you put hay in for a horse to eat. Have you never filled a ratel?”

“Oh, of course!” said Jacques, “Yes, Paul, we have rateux for horses as in other lands, no doubt!”

“I see,” said Bávlos. Ruto must definitely be from France. And if that was the case, then perhaps Rut-aimuo really was hot and burning. It was Ruto that played this trick with the wagon wheel and it was the guardian angel that revealed the truth.“Thank you, my guardian angel for this help,” said Bávlos gratefully.

“It is my duty,” said a voice in reply.

That night, Bávlos and Jacques found an inn to stay in in the heart of the bustling city of Metz. The two friends agreed to share their bed with Bertrand again, just as they had in Lëtzebourg. But this evening, Bávlos had a terrifying dream. He saw a great city by he sea, its towers tall and magnificent against a sky of steely gray. A lone ship was approaching the harbor. It sailed to the shore with only a few sailors manning it and then remained near the pier while the sailors jumped off to look for supplies. As they rushed off the ship, Bávlos saw someone else aboard: a tall, evil man dressed entirely in black. He had saddled a tall black horse which he suddenly mounted. In an instant, the horse leapt over the railing of the ship and alighted on the pier. From there horse and rider charged down the shore entering the city. Bávlos watched them disappear into the maze of streets and alleys that made up the city. He felt a great uneasiness, nearly a panic. “Ruto!” he cried aloud. “It is Ruto!”

Before he knew it Bertrand and Jacques were shaking him vigorously, trying to wake him up. “You have had a nightmare,” said Jacques. “Get some rest now. It is never good to speak of the evil one on an afternoon if you want to sleep well that night!”

“Can you please keep it quiet,” grunted Bertrand. “I’ve got a long way to travel tomorrow as well.”

“I am sorry,” said Bávlos, ‘Pleasant dreams to you.” He closed his eyes but could not forget the terrifying image of Ruto, unleashed upon the city.