Part II. The Hansa Lands and France

Chapter 31. Lëtzebourg and the Duke [November 10, 1347]

Cultural Explanations

|

Part II. The Hansa Lands and France Chapter 31. Lëtzebourg and the Duke [November 10, 1347] Cultural Explanations |

|

|

In this chapter Bávlos hears about the duke Jang de Blannen and the Battle of Crécy | ||

| The Castle at Luxembourg |

In this chapter, Bávlos travels south and spends the evening in a village situated alongside the great castle of the duke of Luxembourg, known in the local language as Lëtzebuerg.

|

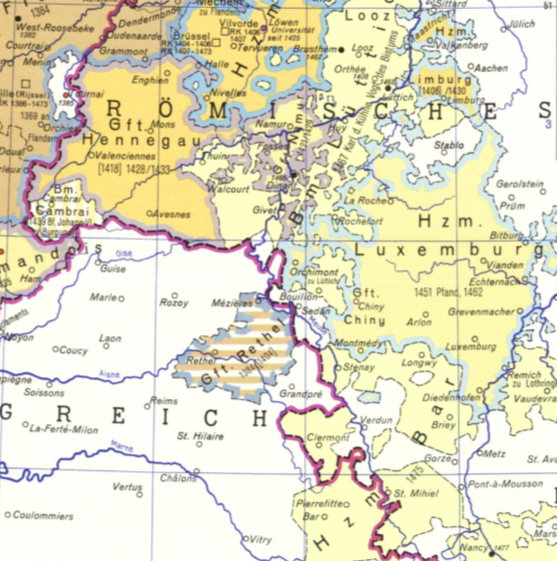

| Map showing the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg during the fourteenth century. |

Bávlos hears the local language, eis Sprooch, a Germanic language known today as Luxembourgish. He also witnesses life in a region that straddles the great east-west linguistic divide of central Europe: Germanic languages on the north and east, Romance languages on the west and south. Jacques is a speaker of French, but--like most of the people in the region--shifts easily and scarcely without thought between his own language and one or more of the Germanic languages spoken by others in the locale.

In the medieval period, local languages enjoyed a fair degree of prominence. All important documents were written in Latin, so the vernacular was simply a language of convenience, and in this context, Luxembourgish was just as valid a mode of communication as French or Low German. With the rise of European nation states, Latin declined, while some local languages became more important than others. French and High German were the big winners in that struggle in Central Europe, although Dutch managed to rise to some prominence as well. Strikingly, even today, there are many in Europe who are not even aware of the fact that Luxembourgers have their own language (with prominent variations in dialect to boot!).

The innkeeper laments the death of the duchy's longtime ruler, Jang de Blannen (1296-1346). At the time when Bávlos is passing through the village, Jang has been dead just a little more than a year, and the innkeeper is still tearful about his passing. Raised in Paris, Jang sided with Philippe VI in his dispute for the throne of France against Edward III of England, a quarrel which led to a century of battles and destruction known as the Hundred Years' War (1337-1453). Jang had indeed fought alongside the knights of the Orden against the Lithuanians and became blind during that military campaign. He became famous for later generations by fearlessly entering into the Battle of Crécy, despite his near complete blindess, a tale that was told over and over again throughout Europe in the centuries after his death. According to the innkeeper, his banner was taken by Edward the Black Prince as his own in tribute to the elder warrior. Jang was succeeded in Luxembourg by his son Karl IV (1316-78). In addition to his title as duke of Luxembourg, Karl was crowned King of the Romans in September 1347, only shortly before Bávlos's arrival in Luxembourg. He eventually became crowned as Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. In the innkeeper's eyes, however, he seems to hold little of the appeal or respect that she shows for the only duke she had known in her life, the aged duke Jang.

The Battle of Crécy took place on August 26, 1346. A major battle of the earliest phase of the Hundred Years' War, the battle pit the troops of the English against those of France and its allies. The details of the battle--the superiority of Welsh archers over the Genoese crossbowmen, the slaying of wounded knights, and the death of Jang and his assistants--are all factual. You can read a good article about the tactics of each side HERE. The battle announced emphatically that the age of chivalric warfare was over and that a new era had begun. Edward and his successors would repeatedly call forth new tactics and new war technology to try to prevail against the French, who enjoyed the advantage of fighting on home ground. Bávlos will learn more about this war in coming chapters.

|

| Fifteenth-century illuminated depiction of the Battle of Crécy. Note the struggling Genoese crossbowman on the left and the doughty Welsh longbowmen on the right. Image courtesy Wikipedia Commons |

Edward the Black Prince (1330-76) was regarded as a great hero by the English chroniclers, but as a villain by the French. At the time of the Battle of Crécy he was only sixteen years old, yet he fought actively in the battle, as well as in many subsequent undertakings. According to accounts of the time, he acquired his banner from Jang de Blannen, adopting it as his own as a mark of respect to the aged knight. The banner, three feathers surmounting a crown, with the motto Ich dien ("I serve"), remains the official banner of the Prince of Wales.

|

| Heraldic device of the Prince of Wales. Photo by Alf, courtesy Wikipedia Commons. |

It is characteristic of Edward that his act both evinces a sense of old notions of chivalry and yet occurred in the context of an unprecedented break with earlier courtly rules of warfare. The refusal of the English to ransom fallen knights ended decisively centuries of custom that dated back to the era of Jacques's hero Charlemagne. Although popular among the English, Edward never succeeded to the throne of England, since his father outlived him by one year. After the death of Edward III, the throne passed to the Black Prince's young son, who became King Richard II.

The North Sámi terms riidu and shiervi mean indeed what Bávlos says they mean.