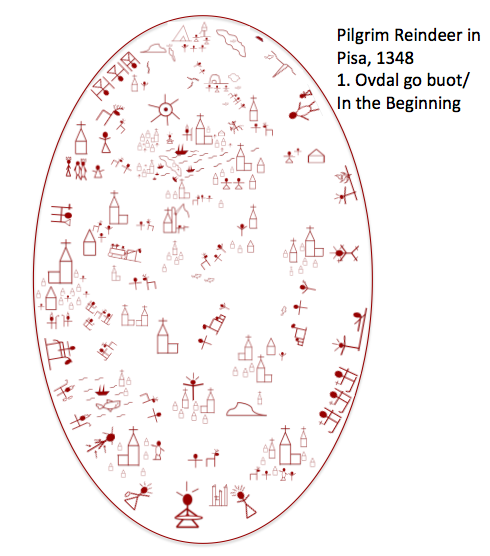

Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348

a free multimedia novel by

Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison

|

Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348 a free multimedia novel by Thomas A. DuBois, University of Wisconsin-Madison |

|

|

|

|

|

Pilgrim Reindeer in Pisa, 1348

As the deer longs for the running waters,

So my soul longs for you.

Part I Setting Out 1. Ovdal go buot/In the Beginning

What does “he ascended” mean, except that he also descended,

Into the nether realms of the earth?

Pisa was already five centuries old on the windy morning that an intrepid fisherman proclaimed the death and resurrection of his master to a crowd of skeptical onlookers from a window in a house in the city of Jerusalem, fifteen hundred miles away. Two hundred years before the birth of that Savior, Pisa had become a prosperous city of the Roman republic. Eleven hundred years after that Savior, at the pinnacle of its worldly might, Pisa’s militant archbishop—one of many the city produced—would ride into Jerusalem as part of the First Crusade, eventually becoming its Patriarch. Pisan colonies sprang up in Antioch and Tyre, Cairo, Caesarea, and Constantinople, sending wealth back in masses to the Tuscan center. Sardinia and Corsica numbered as city possessions, and everywhere they went the Pisans defeated their rivals: Saracens, Byzantines, or Italians alike. By the mid-twelfth century, even the pope was Pisan, sending soldiers off once again for the Second Crusade. Always open to all possibilities, Pisa entertained an antipope as well, the puppet of the Holy Roman Emperor. And, in an act that mixed the seriousness of piety with the glee of plunder, another Pisan archbishop would return from the Fourth Crusade possessed of a cargo of holy dirt: soil taken from the very hill of Golgotha, in which the city’s finest dead would ever more be buried. The triumphant citizens started a kind of church around this dirt, the Camposanto or “holy field,” with a roof and outer wall intact, but an inner wall left open to the air and rain of a central cloister. Jerusalem had come to Pisa: the world lay at its feet.

But all things are passing in this vail of tears. Less than a century after that moment, the Genoese would defeat the Pisans at sea, eventually arriving to destroy the city’s port and rub salt in its grounds. Recoiling from this shame, perhaps, as well as from earth stolen from a gallows site, the river changed its course, leaving the ruined port unusable for the passage of cargo ships. Shifting soils upset the city’s finest tower, pushing it to sag and lean despite the efforts of successive builders to make it stand erect. The colonies disappeared, the islands were lost, the fame of the Pisans ebbed. In 1348, in what must have seemed a final strife, the Plague swept through the city, leaving heaps of corpses in its wake and reducing the population by half. How could people not take such turmoil as a sign of the anger of God?

On a clear morning in the aftermath of those events, a local painter carefully spread the first giornata of plaster on a sheltered wall inside the Camposanto and began to paint. His fresco, a work that we have come to call “The Triumph of Death,” now covers a huge swath of wall. It does little to cheer the city’s grieving, then or now. At its lower end, a row of open coffins display corpses in various degrees of decomposition, encircled and gnawed by teaming serpents, sources of marked displeasure for the mounted nobles who linger and chat nearby. A handkerchief to the nose discreetly hints at their distaste for the smell of rotting flesh, or perhaps it hides a piece of herb or fruit meant to ward away contagion. Batwinged demons descend from the heavens, accosting similarly heedless dancing women clustered by a musician in a grove at the far right of the fresco. The demons gambol and swoop, aiming at the sea of lifeless body parts that lie strewn across the central ground of the painting. The demons skirmish with angels for the newly liberated naked souls emanating from the bodies: they will spend their eternity in torment or delight, depending on which winged spirit proves best at the aerial tug-of-war. Rich and poor, healthy and ill, layman and cleric alike: all succumb to death. To the left of the carnage, an erstwhile monk tries to convince the jaded living of the need to repent, while his brethren, arrayed on a landscape of rocks and precipices that would not sustain an onion, model the life of ascetic denial that, perhaps, can turn away the seeming inevitability of damnation. And there, in their midst, in a singular image of calm and stasis, kneels a monk in the act of milking a deer. Art historians maintain it is a goat, because such makes sense in the context of fourteenth-century Italy. But the animal is a deer, almost certainly a female reindeer who has recently dropped her antlers, a sign that she has calved.

Who was this monk engaged in such seemingly anachronistic behavior: where did he learn the art of reindeer husbandry? Why does he figure in a painting of the Triumph of Death in a city in the heart of the Mediterranean? What will he do with the milk he is collecting: will he drink it fresh or is it destined to become an Italian cheese now lost to us through the centuries? For answers to these questions, we must turn far, far to the north, to a distant patch of forest, meadow, and marsh near a lake called Sállejávri in the shadow of a mountain known to all as Sállevárri.